All women employed under the conditions approved shall be employed only for the duration of the war and shall be replaced by men as they become available.

Prime Minister John Curtin, October 1941

The men were the bosses; the women did the work.

Elly Blackshaw, munitions worker

A workforce transformed?

Australia’s involvement in World War II created a demand for labour in both the services and wartime industries. At first there was little impact on women, but as more men left to fight, women were needed to fill the gaps. Many relished the challenge to ‘do their bit’. By 1943 there were more women in the paid workforce than ever before and this included many married women whose husbands were in the forces. But the longer-term implications of this period for women’s rights in the workplace are still debated by historians.

A workforce segregated by sex

On the outbreak of war Australia’s workforce was highly segregated by sex. Many jobs were classed as either ‘men’s jobs’ or ‘women’s jobs’, and workers were paid accordingly. But by mid-1941 it was apparent that Australia would not be able to meet its wartime obligations with the existing workforce, and the government began to consider recruiting women in large numbers. The entry of Japan into the war in December 1941, with the pre-emptive strike at Pearl Harbor, confirmed the need for all capable workers. As men from essential industries were conscripted into the armed forces to fight in the new Pacific conflicts, women became the target of government’s recruitment drives. Over the next few years the workforce in some industries was transformed, as women took up the challenge of jobs in munitions and heavy engineering, industries that were almost exclusively masculine before the war. White collar positions opened up to women too, and some women found themselves offered positions of authority for the first time. Attitudes to women workers changed, with many commentators watching the transition in wide-eyed astonishment.

But the transformation was only ever partial and it was always intended to be short-lived. Although many women in former ‘men’s’ industries were paid better during the war, very few achieved equal pay, while the pay rates in traditional female industries actually stagnated. And with the end of hostilities, returning servicemen reclaimed their jobs, leaving women to revert to traditional female industries, or leave the paid workforce for home-making and motherhood.

The need for women workers

Within a year of the outbreak of war it was apparent that Australia could not continue to meet its wartime commitments in both the services and industry without recruiting women. The RAAF for example, had an acute shortage of telegraph operators from October 1940, but there was great reluctance to open such jobs to women. A combination of prejudice and hard-headed self-interest fueled this resistance. Government, trade unions and employers agreed in their opposition, though for different reasons. Trade unions feared competition to men’s jobs from low-paid female workers, employers in ‘male’ industries doubted that women could perform heavy tasks, or tasks requiring high levels of skill, while those in ‘female’ industries feared competition for workers from better-paid jobs and the resulting rising pressure on wages. Government was torn both ways, not least as an employer of many thousands in the services. The Australian Air Force was the first to concede, forming the Women’s Auxiliary Australian Air Force (WAAAF) in January 1941. The WAAAF recruited women to work as telegraph operators as a ‘temporary measure’, on two-thirds of the male rate of pay.

Recruitment poster for the women’s auxiliary services and for essential war work.

Reproduced courtesy Australian War Memorial

The women in these posters were invariably pretty, well-groomed, feminine and cheerful.

Take a Victory job

The decision to recruit women workers was one thing: persuading women to seek such work was quite another. There was widespread concern that women would lose their femininity if they joined the auxiliary services, or took a job in an engineering factory, and not all of that opposition came from men. Government’s initial response was a propaganda campaign. Colourful posters featuring attractive women were displayed at all recruiting depots, and women were urged to ‘do their bit’ for the war effort by taking a ‘victory job’. Newsreel features were made and shown in cinemas before the main films. They showed cheerful ‘girls’ enjoying the freedom of life in the Women’s Land Army, or ‘doing their bit’ in the factories. Popular women’s magazines like the Australian Women’s Weekly printed many features promoting women’s war work. These articles supported the new, expanded roles for women, but also reassured their readers of the enduring femininity of such women workers. Examples of some of these press features are included below. They were not limited to women’s publications: the mainstream press also took a great interest in women working in non-traditional roles. Often commentators expressed their surprise at the achievements of these women workers, and their patronizing tone is very evident, but their support of women’s work was clear.

Recruitment poster for essential industries, 1943

Reproduced courtesy Australian War Memorial

This woman is rather more serious compared to the friendly, smiling faces in the poster above. Her clenched fist signals determination while the Australian flag in the background testifies to her patriotism. Posters like these underlined the message that women’s contribution was essential for Allied victory.

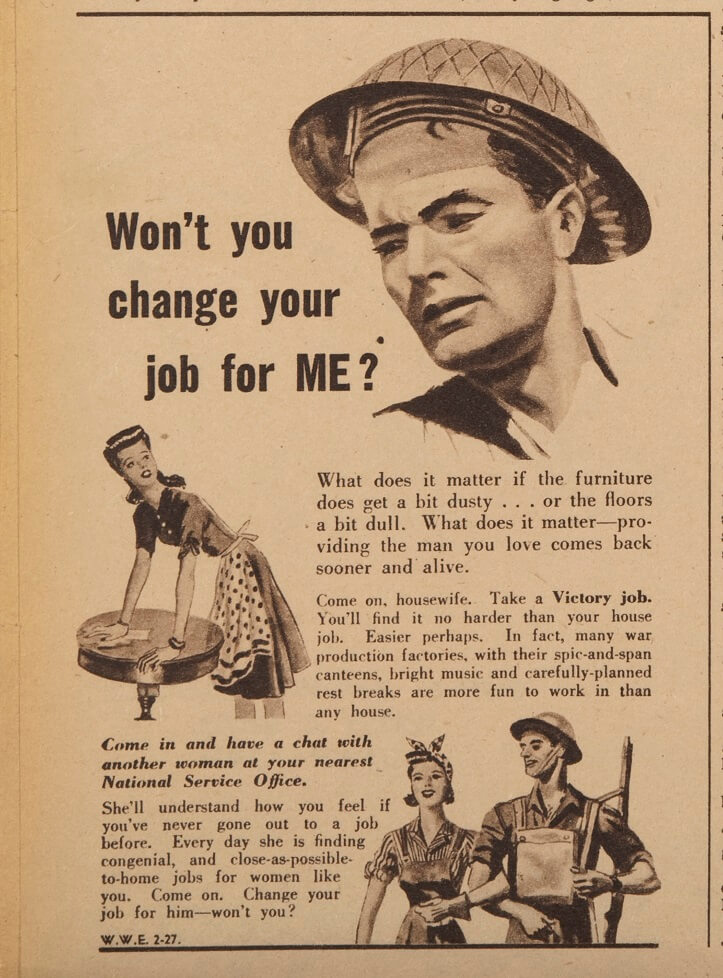

‘Won’t you change your job for ME?’ Poster advertising Victory jobs, April 1943.

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

This poster was aimed at the ‘housewife’, urging her to take on a Victory Job for the sake of her man in the forces. The description of war production factories with their ‘spic-and-span canteens, bright music and carefully planned rest breaks’, was idealistic in the extreme. Although it reassured the reader that she would ‘find it no harder than her house job’, it omitted to consider that the ‘house job’ would still be there at the end of her other shift! No provision was made for child care either, so mothers who wished to work had to make their own arrangements, generally with neighbours or family.

World War II provided some opportunities for female journalists too, not all on women’s magazines. By 1941 the ABC employed 19 women as announcers, and over 20 women were accredited war correspondents. They did not, however, report on action at the front: mostly they were expected to provide ‘human interest’ stories from behind the lines.

Melbourne journalist Adele Shelton-Smith was the first Australian woman to report from overseas. Representing The Australian Women's Weekly, she went with a photographer to Malaya in 1941. Banned from writing articles about the war, Shelton-Smith wrote about daily life in the camp; the soldiers’ ‘healthy meals’ and their living quarters, ‘more comfortable than home’.

Author: Margaret Anderson

Find out More | Next page: Equal Pay for Equal Work