Cover image from The Australian Women’s Weekly, 13 September 1941. Image courtesy National Library of Australia.

This striking cover created by cartoonist and illustrator Virgil Reilly was published by The Australian Women’s Weekly on 13 September 1941. It shows soldiers hastening towards a burning city, while searchlights beam skywards, illuminating aircraft formed into a dramatic ‘V’ for Victory. In the centre of the formation is a woman, shown naked, with her arms uplifted so that her torso mimics the ‘V’ formation of the aircraft. Flames preserve her modesty. She is looking towards the sky, her mouth open as if calling the aircraft on. A glittering garland of lights, that seem to mimic the aircraft lights, encircles her head.

The context for the image was almost certainly the bombing ‘blitz’ conducted by the German Luftwaffe (air force) against British cities and industrial targets from September 1940 to May 1941. The last attack on London took place in May 1941 and caused thousands of fires. Although hugely destructive of British cities, ports and industry, German losses were also high and the bombing campaign did not achieve its objective of disabling Britain’s defence capacity. This may explain the symbolic depiction of the ‘V’ for Victory. The defiant two fingered sign of ‘V’ for Victory was also first used by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill in July 1941. Churchill was apparently aware that the gesture had another, ruder, meaning – literally ‘up yours’- and enjoyed the double-entendre.

Australia as a woman

The symbolic use of the female figure in this illustration may have been read on a number of levels. There was a long allegorical tradition of presenting nations as female figures. Other civic virtues, like ‘justice’ and ‘liberty’ were also presented in the female form. This tradition dated from ancient times, but became popular again in modern history from the late-seventeenth century, when the female figure of Britannia, modelled on classical depictions of the Ancient Greek goddess Athena goddess of war and women, (and her Roman counterpart Minerva) re-appeared. Britannia was the immediate model for the many depictions of ‘Australia’, created from the mid-nineteenth century, long before the united country of Australia existed in fact. The depiction of Australia as a woman was popular throughout the late-nineteenth century and well into the twentieth. It was never an exclusive allegory of nation. The Bulletin’s ‘Little Boy from Manly’ was an alternative symbol, especially when a less dignified image was called for, but the female form of Australia was almost always used in ceremonial or formal depictions of nationhood. This female allegory of nation was especially dominant during the period around Federation and again during the First World War, but declined in popularity during the 1930s, only to reappear during World War II.

Virgil Reilly’s woman combines elements of the classical goddess, with those of a modern woman. She is unclothed, suggesting vulnerability, but also ardour. Popular images of ‘Liberty’ (the French symbol of ‘Marianne for example) often used the symbol of the bare-breasted woman. And the lights around her head suggest a diadem. But she is also unquestionably a modern woman, with contemporary hair and make-up. In this sense she could also stand for the women of Britain or Australia, exhorting their men to victory and assisting in that fight themselves.

Readers of The Australian Women’s Weekly were probably more familiar with this kind of symbolism than we are now. Classical goddesses adorned statuary on buildings throughout Australian cities, not least as symbols of ‘blind Justice’ outside every law court. Cartoons depicting Britannia and her ‘daughter’ Australia were commonplace, while the ‘V for Victory’ symbol was immensely popular during the war throughout the British Commonwealth. So many elements of this cover image were probably recognizable to readers of the Weekly. But even without its allegorical meanings, Virgil’s image was a dramatic depiction of the desperate struggle then underway in Britain, and by inference, was a reminder of Australia’s likely fate should the British Empire be defeated.

Cover image from The Australian Women’s Weekly, 12 October 1940. Image courtesy National Library of Australia.

Britannia was a well-known figure throughout the war. In the previous year, at the height of the Battle of Britain, the Weekly published a cover image drawn by another artist, showing Britannia threatened both at sea and in the air. In this illustration she is dawn in full battle dress, with plumed helmet (the familiar Athena/Minerva identifier), gold breast plate, sword and trident. A cloak in the form of the Union Jack balloons behind her. Her expression is resolute, as her outstretched hand launches a British aircraft into the sky. Other planes circle her head, while at her feet, threatening southern England, are destroyers and submarines. The image was entitled ‘Forever England’.

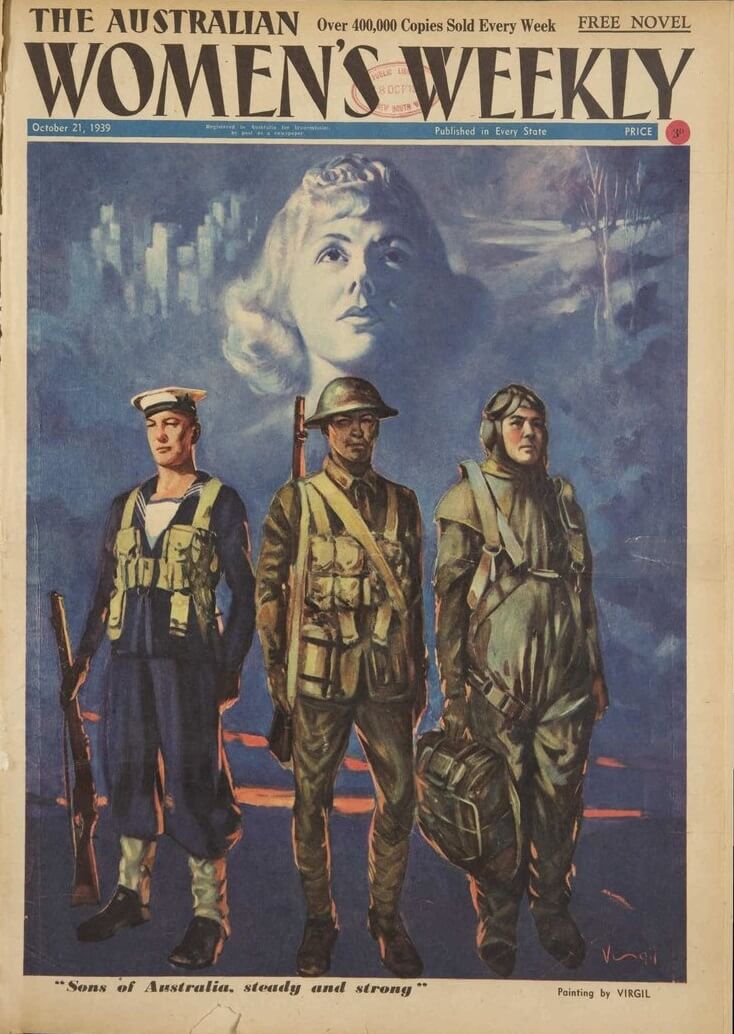

Cover image from The Australian Women’s Weekly, 21 October 1939. Image courtesy National Library of Australia.

Right at the start of the war Virgil Reilly had created another cover illustration for the Australian Women’s Weekly. Three servicemen stand in the foreground of this image, representing (L-R) the navy, army and air force. They are realistic figures, drawn from life, and are shown standing at ease, though in full battle kit. The servicemen were Charles Henry Bruce RAN, Gavan Reilly AIF (the artist’s son) and Squadron Leader Arthur Norman Wright, RAAF. Tragically all three of the young men depicted in this illustration were killed in action. The ghostly female figure shown in the background could be either allegorical or real. With her eyes fixed upwards, in either fear, or hope, she might be the nation of Australia, inspiring her ‘sons of Australia’, or she might represent the women of Australia, left at home. She was said to be based on Virgil’s then wife (he was married five times). The shadowy background shows both city and country united in war and sacrifice. Virgil entitled his drawing ‘Sons of Australia, steady and strong’.

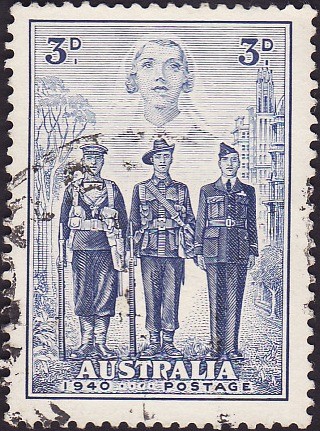

This cover illustration was later used as the basis for Australia’s first wartime stamp issue, apparently the first such issue in the British Commonwealth. Although Reilly has been credited with the design, it was, in fact, very different after being re-worked in the postal design office.

The postage stamp design also foregrounds three servicemen, one each for (L-R) the navy, army and air force, but in this image they all stand to attention. While the navy and army servicemen are in battle dress, the pilot is in full dress uniform. The realism and humanity of Virgil’s depiction is missing in the stamp design. Although later commentary repeated the information that all three young servicemen were killed on active service, more recent philatelic research suggests that this was not the case. According to records from the Postmaster General’s Department the men depicted on the postage stamp were meant to be generic servicemen, and were based on employees in the design office, all of whom survived the war. The female figure in the background is also different. On the postage stamp she is no longer Australia, or the generic women of Australia, but has become a nurse. The twin images of city and country remain, though in reverse. A philatelic blog post published in 2013 shows two previous designs for the stamp, both of which used Reilly’s figures.

The artist, Virgil Reilly, was a cartoonist, book illustrator and comic book artist. Although born in Creswick Victoria, he spent most of his working life in Sydney, working first for Smith’s Weekly and then for the Australian Women’s Weekly throughout the war. After the war he drew for Sydney’s Daily Mirror and Melbourne’s Truth. In 1958 he won the inaugural Walkley Award for the ‘Best Creative Artwork or Cartoon’ for a cartoon drawn to mark Legacy Week.

Further reading

Margaret Anderson, Julia Clark & Andrew Reeves When Australia was a woman: Images of a Nation. Perth, Western Australian Museum, 1998

Marina Warner Monuments and Maidens: The Allegory of the Female Form. London, Vintage, 1996 (first published 1985)

John Pearn & Bronwyn Wales, ‘How We Licked Them: the role of the philatelic medium’, Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland, 15, 2, (1993), pp. 117-20. Note that subsequent research suggests that those depicted in the stamp are not those drawn by Reilly. See: https://australianstrampcatalogue.com/1940.ph

Author: Margaret Anderson