Women in munitions and engineering factories

Some of the jobs performed by women during the war were both difficult and dangerous, especially the work of those in the munitions industry. Melbourne was a long-time centre for munitions manufacture: in 1939 89 per cent of those employed in this industry nationally worked in Victoria, most of them in Melbourne. The main centres were in Maribyrnong, Footscray and at Fishermans Bend. For obvious security reasons, this essential industry was decentralized during the war, but at the peak of munitions manufacture in 1943, one third of the 60,000 employees in the industry still worked in Victoria. They were a significant part of the workforce in Melbourne’s western suburbs.

A male domain

Before the war the vast majority of munitions workers were men, but as wartime production increased and more men were called to enlist, government turned its attention to recruiting women. By 1943 more than half of all munitions workers were women and their contribution was essential to Australia’s wartime production of armaments. Many of these women volunteered for munitions work, anxious to contribute directly to the war effort. Some had brothers or husbands in the services. For others it was an economic decision, as the Women’s Employment Board began to award women doing ‘men’s’ jobs higher wages.

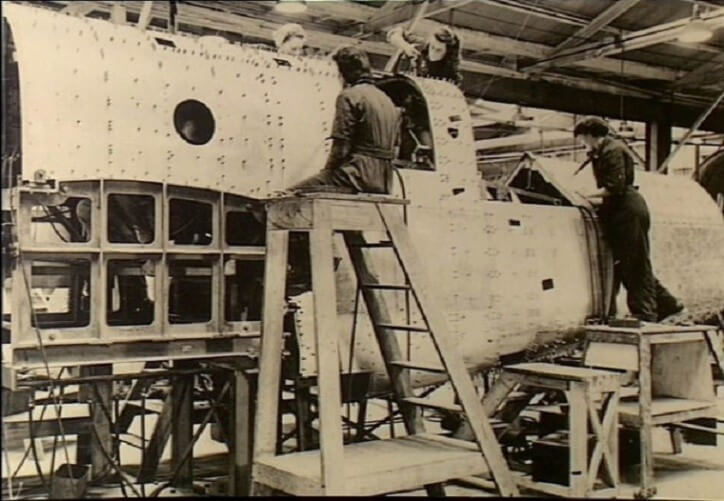

Two women working alongside an older man in an aircraft bomber factory

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Woman at Smith and Searle’s Factory, South Melbourne

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Smith and Searle’s Factory was said to employ women almost exclusively. It manufactured parts for munitions and for fruit canning. One newspaper article claimed that the factory employed only one man, to do the heavy lifting and to make the tea!

Some workers were effectively industrial conscripts. Government established a Manpower Directorate in early 1942, (following an earlier Manpower Committee,) initially to direct the labour of men, but in January 1943 its powers were extended to women. All childless women aged between 18 and 45 years were required to register, and the first forced appointments were made in March of the same year. Women who refused appointments were threatened with imprisonment, although some women challenged the decisions of the Directorate successfully. Middle class women could often mount successful challenges by citing their work for various voluntary associations. Government was well aware of the value of the work performed by these voluntary associations and had no wish to compromise their activity. Other women took pre-emptive action, finding themselves jobs they preferred in essential industries to avoid direction.

The munitions factories

Conditions in the munitions factories varied, sometimes depending on the age or size of the plant. Some were government facilities: others private companies. They varied from large, sprawling facilities, like the Defence Explosive Factory at Maribyrnong (government owned), or the Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation (a private company) at Fishermans Bend, to small, family-owned engineering works, producing smaller component parts. Conditions of work might vary enormously too, with some small engineering works leaving much to be desired.

Women working at the Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation Factory at Fishermans Bend.

Reproduced courtesyAustralian War Memorial

Photographs like this were popular during the war, emphasising what women could achieve in ‘men’s jobs’.

The story of Elly Blackshaw

Elly Blackshaw’s story was recorded in the late 1980s by two mature-age history graduates, Betty Goldsmith and Beryl Sandford and was published amongst others in a Penguin publication The Girls They Left Behind. Elly lived her early adult life in Sorrento, before moving to Melbourne in the late 1930s. She and her husband managed to build a house, which was completed just as war was declared. When her husband enlisted in the Army, Elly found herself with time on her hands. She found a job near home in a woollen mill, replacing male night-shift workers who had enlisted, but found the conditions appalling:

The smell of scoured wool was awful, the heat oppressive and there were no facilities for washing in the toilets. It was just a dirty job, so I left.

Despite working the night shift and half of each Saturday, her pay was only £2 per week – half the men’s wage. She applied instead to work at the Maribyrnong Explosive Factory.

Elly was assigned to the detonator section, one of the most dangerous parts of the factory, where she worked as a ‘filler’. The detonator section was located about a mile from the rest of the factory as a precaution should there be an explosion. As she remembered:

Everything on this section was painted red. The men wore red suits, the feltex on the floor was red, the powder boxes were red. All to remind us that everything was dangerous.

Workers wore wool, as a safety precaution and they were searched routinely on entering to check for matches or cigarettes. The temperature in the factory was maintained at a steady 90 degrees Fahrenheit (32° C) to ‘keep the powder dry, so we sweltered in summer’, she recalled.

Elly’s task as a filler was highly dangerous.

I was a filler. My job was to work in a room by myself. The powder I held in my hands was enough to blow up a ship as big as the QE2. I sat on a stool with my arms around a shatterless glass and steel shield, filling caps in steel moulds and passing them to a sill the size of two bricks, where a hand would appear (if you cared to look up), and take these measured shells to press.

Almost every day someone was hurt, some were blown to pieces, building and all. Once three men went up with the building they were in…

We got 1s 6d a day for danger money. I came to the conclusion that the government of the time didn’t consider we were worth much… .Two of my friends had detonators explode in their hands, one died years later with pieces of steel still in her hands. I developed the blood pressure of a woman of eighty although I was only thirty-five. The powder I handled every day was full of mercury... .There was no compensation for this mercury poisoning, yet they could not have done without us.

Elly’s job ended with the end of the war. There was less need for munitions in the last months of the war and men were already beginning to come home to resume their former jobs. Her husband eventually came home too, after being a POW in Borneo (Malaysia). He had terrible injuries and required expensive nursing for the rest of his life. Incredibly he was initially refused a pension, a situation that was only resolved one year before his death 20 years later. ’It took all the money we had for doctors’, Elly recorded. In the end Elly herself had a nervous breakdown. At the time she recorded her memories she concluded: ‘Now I muddle along as best I can on a war widow’s pension.’ Somewhere along the way she had children, but whether before or after the war, she did not say.

Elly Blackshaw’s memoirs were published in Betty Goldsmith & Beryl Sandford (eds) The Girls they Left Behind: Life in Australia during World War II – the women remember Ringwood, Penguin, 1990, pp. 178-81.

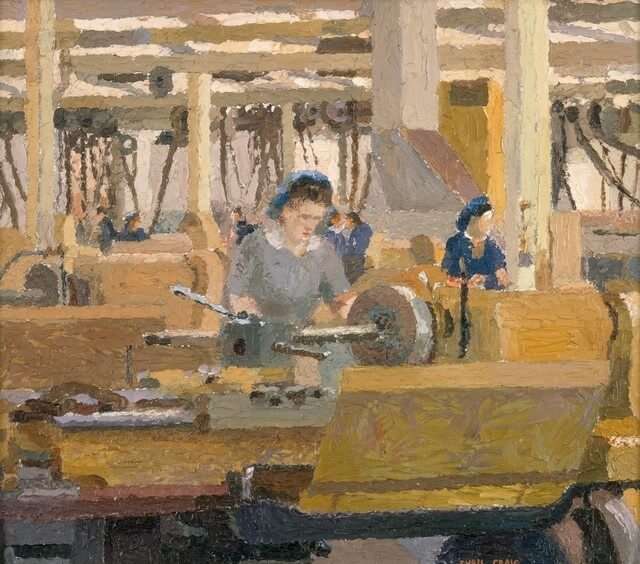

Working in the detonator section, Commonwealth Explosives Factory, Maribyrnong, by Sybil Craig, artist, c.1942.

Oil on canvas.

Reproduced courtesy Australian War Memorial

Munitions workers in a Bendigo factory, April 1943.

Reproduced courtesy Australian War Memorial

Women munitions workers in an ordnance factory in Bendigo heat the barrel of a 3.7 inch anti-aircraft gun in preparation for the straightening process. Tasks like this were invariably performed by men before the war. Although this factory appears to be spacious and clean, many were not. Note also the absence of any safety equipment.

A woman working at a Le Blond Shell Boring machine in the ordnance workshop at the Commonwealth Ordnance Factory, Maribyrnong, by Sybil Craig, artist, c.1942.

Oil on canvas.

Reproduced courtesy Australian War Memorial

This painting is by Sybil Craig, one of three women recruited as official war artists in World War II, to record women’s contribution to the war effort.

Sybil Craig painted women at work at the Commonwealth Explosives Factory at Maribyrnong. She produced over 70 paintings, held by the Australian War Memorial.

Miss F. Krizos, a biochemist at work in a munitions factory

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria.