I told the Sisters what was to happen, and also made it clear to them that those who volunteered would stay behind with the hospital and that they would in all possibility be captured. I asked them to write on a slip of paper their names and either “stay” or “go” and hand them to me … Not one Sister wrote “go” on the paper. I then selected 39 sisters to remain [with me].

Matron Kathleen Best, Australian Army Nursing Service, Greece, April 1941

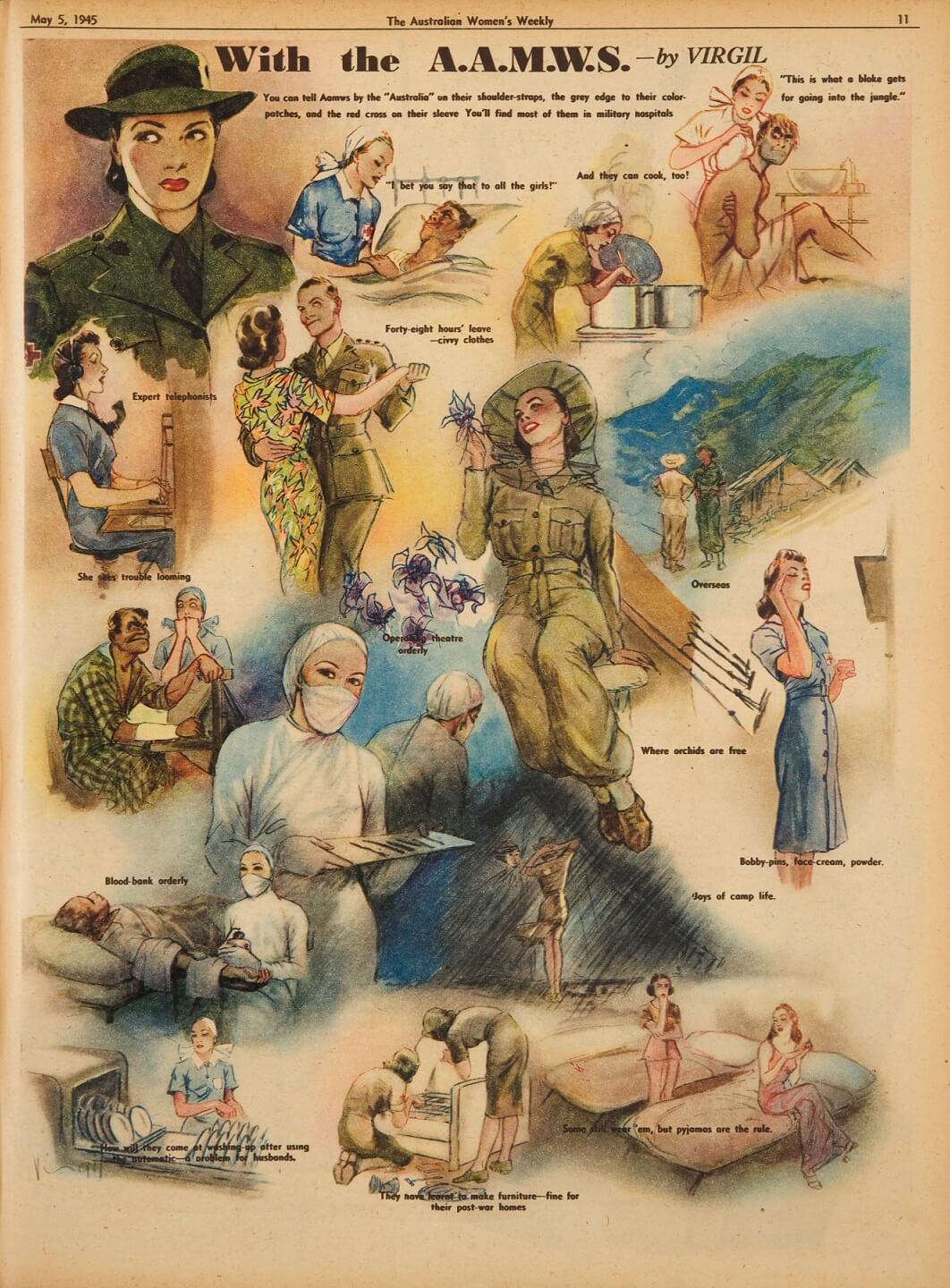

Over 4,000 women joined the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) during the Second World War. Another 660 entered the Royal Australian Air Force Nursing Service (RAAFNS) or the Royal Australian Naval Nursing Service (RANNS). An additional 8,000 women made up the Australian Army Medical Women's Service (AAMWS). AAMWS were not trained nurses, but worked as nurses' aides, or in clerical and technical positions.

All of these women broke the traditional boundaries of home and family to further the war effort, proving to be courageous and resilient.

Where there are men fighting, there are always nurses - Sister Florence Syer

World War II brought nurses closer to combat zones than in previous conflicts, challenging prevailing views that war was ‘men’s work’. Australian nurses served in the Middle East, the Mediterranean, Britain, Asia, the Pacific, and Australia –wherever Australian troops were deployed. Seventy-eight Australian nurses died, primarily through enemy fire, or whilst prisoners of war. Some nurses even carried weapons for protection.

The Australian Army Medical Women’s Service (AAMWS), established in December 1942.

The Australian Women’s Weekly, 5 May 1945, Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

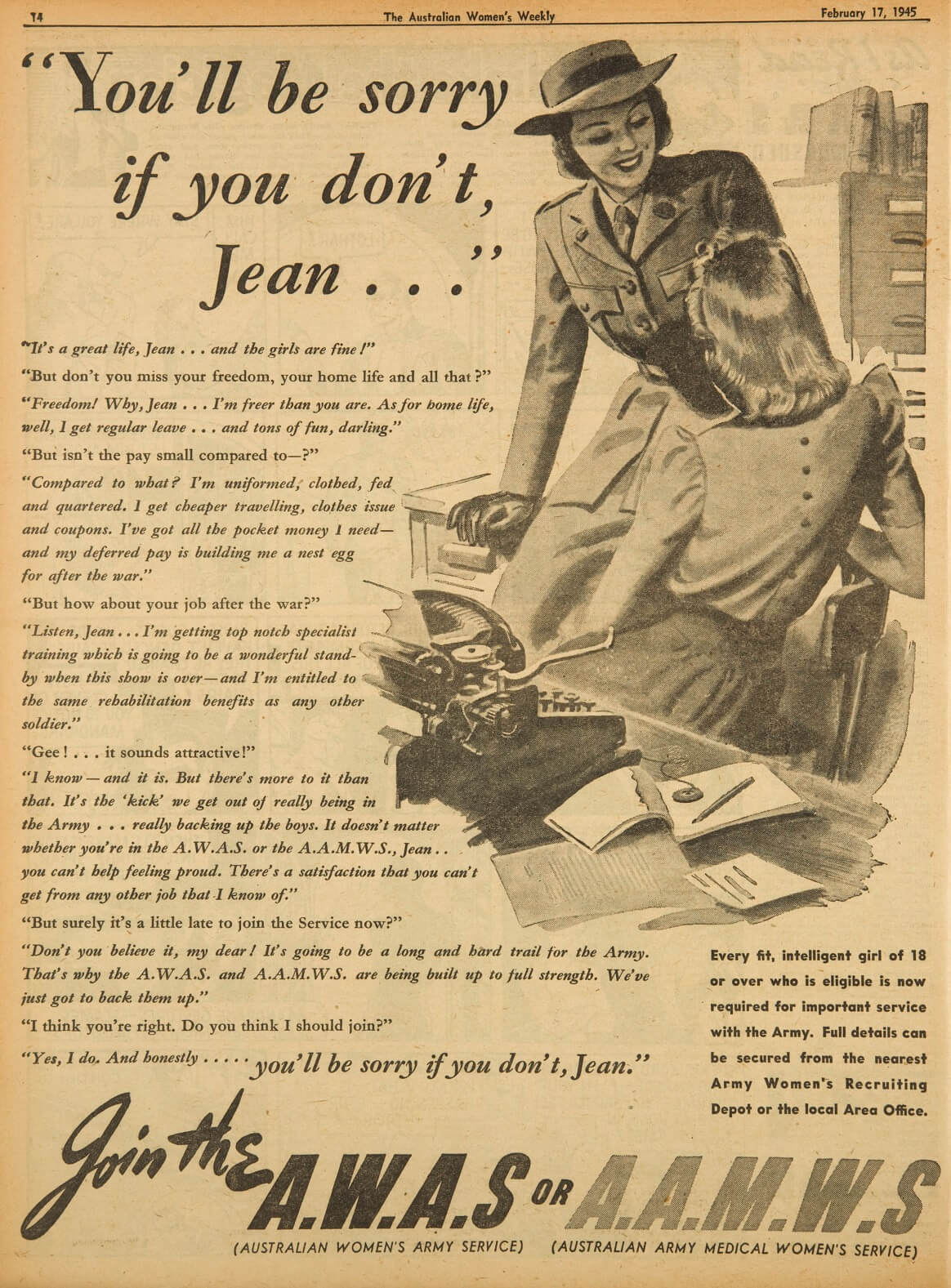

‘You’ll be sorry if you don’t, Jean…’ Recruiting poster for the AAMWS, published in The Australian Women’s Weekly, 17 February 1945

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

The majority of the AAMWS were drawn from Voluntary Aid Detachments (VADs) who already had hospital experience. Recruitment posters like this managed to emphasise service, whilst emphasising femininity and traditional gender roles.

By the 1940s, the professional status and prospects of women doctors had improved. More hospital residency posts were available for women doctors and medical research and scientific positions included women graduates. The Army lagged behind. Only 26 women doctors served in the Australian Army Medical Corps during World War II, mostly in administrative roles. No women served overseas: in common with other occupations their work at home freed male doctors for services. Curiously, women doctors received the same pay in the services as their male equivalents, the British Medical Association in Australia insisting on equal pay.

Rank and pay

Member of the AANS were commissioned officers - lieutenants on appointment, rising to the higher ranks of colonel, lieutenant-colonel and major. But very few nurses used their military rank: higher ranks were addressed as ‘matron’, others as ‘sister’. They were not given the same status and pay rates as male officers.

On duty 6.30 pm to find the place v. busy & as night went on it got worse. 23rd Batt. Mach-gunned & patients poured in, theatre going all night. By morning all v. tired. - Sister Nell Bryant, Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS)

The first AANS nurses arrived in Egypt and Palestine in 1940. By 1941, AANS units were working in England, Australia, Palestine, Libya, Egypt, Greece, Eritrea, Syria, Malaya and Ceylon. They worked in all conditions, and in a range of ‘hospitals’ - tents, underground dug outs, huts, evacuated civil hospitals, even palaces, such as the Kaiserine on the Mount of Olives.

Caring for the sick and wounded men and women must have been terrifying at times. The nurses worked during air raids, listening to the bombs dropping and artillery fire, and then treating the horrific wounds.

Nurses working on the hospital ships were not exempt from danger. In the sinking of the hospital ship Centaur in 1943, 11 sisters, including the matron of the ship, were killed.

Many nurses came under direct fire and required evacuation. The nurses in Tobruk assisted with the evacuation of 300 patients, only days before the famous siege. Many, such as Matron Kathleen Best, showed considerable bravery. For her leadership and courage during the evacuation from Greece, she was awarded the Royal Red Cross.

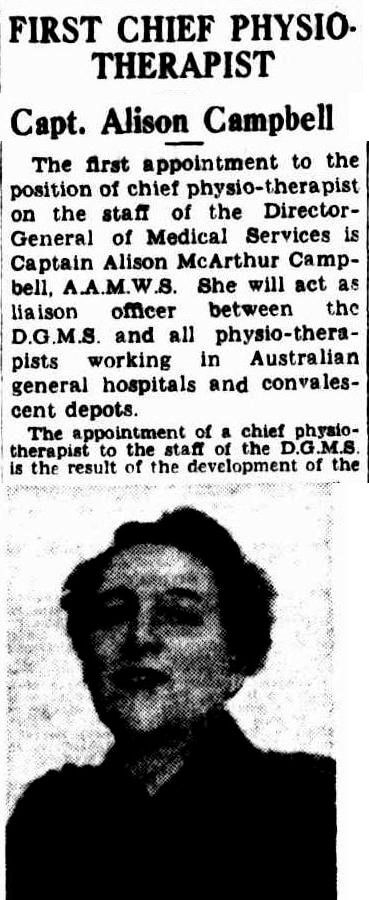

Our raison d’être was simple… We were to work to restore as quickly as possible the muscle power and joint mobility of wounded and sick men. - Alison McArthur Campbell, Chief Physiotherapist, Director General of Medical Service

In 1941 the Australian Army’s first female physiotherapists were dispatched to the Middle East. The physiotherapists (masseuses) served with Australian and British General Hospitals in Eritrea, Greece, Crete, Malaya, Egypt, Gaza, Malaya and Ceylon.

The physiotherapists worked in orthopaedic wards, applying splints and plaster casts. They helped patients to use crutches or walking aids correctly and worked with patients after back, chest and plastic surgery. They treated nerve injuries, encouraged muscular function and showed soldiers how to care for their feet. They played an important role in the rehabilitation of seriously-injured soldiers.

Like their nursing colleagues, physiotherapists worked under trying and dangerous conditions. Leah Knowles was a senior masseuse with the AIF in Greece in May 1941:

Machine gunning woke us regularly every morning and dive bombing sang to us at night. Curfew was 8 p.m. For four weeks this went on. We couldn’t leave the hospital area.

Wounded men came in too tired for anything but food and sleep.

We were always packed and ready to go in a hurry, slept in our clothes, with my tin hat on my head. I suppose I shall wear said tin hat to the races when I get home it’s become such a part of me.

Leah came under fire and required evacuation:

Suddenly we were told to go. Quick. Couldn’t take our kitbags and cases.

We all volunteered to stay. I longed to stay behind even though I am so fond of my family. Many cried. Thirty of us were packed like sardines into military trucks, only room to stand.

You can say what you like, but it does a man a world of good just to be able to look at a woman. – RAAF Airman

The Royal Australian Air Force Nursing Service (RAAFNS) was established in July 1940. Applicants had to be single, female, registered as an Australian citizen, and aged between 21 and 40. They entered the service with the rank of flying officer.

During the first year, the RAAAFNS took on 120 nurses. By 1945 there were 616 members.

The nurses were originally attached to Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) bases in Australia, later moving to New Guinea and the Pacific Islands. In early 1944, 15 nurses were recruited from the RAAFNS to the newly-formed No. 1 Medical Air Evacuation Transport Unit (MAETU). Nicknamed ‘The Flying Angels’, MAETU flew casualties, and later prisoners of war, back to Australia from the Pacific Islands. Within the first year of operation, some 8,000 patients had been evacuated.

Miss Margaret Irene Lang was appointed the first Matron-in-Chief of the RAAFNS. A nurse in the First World War, at the outbreak of World War II she was the Matron of the Police Hospital in Melbourne.

Attached to the Directorate of Medical Services at RAAF Headquarters, Lang was responsible for the organisation of the RAAFNS. She advised the director general on all matters relating to nursing in hospitals, sick quarters and medical rehabilitation facilities, and on the appointments, postings, promotions and discharges of RAAF nurses.

Lang was once described by a journalist as being ‘a small neat woman with a brisk step and a ready smile’. She was known for her untiring efforts for the welfare of her nursing staff, and the patients.

Miss Lang (Matron in Chief) gave us a pep talk. She was a great one for discipline, high standards and strict rules. For example, the RAAFNS were allowed one sherry at a party (two if pressed)! We commented on the narrow uniform skirt; Miss Lang said she would make ladies out of us, even if she had to hobble us.

Mrs Joan Patterson, formerly Sister Joan Loutit, 2nd Medical Air Evacuation Unit (MAETU) RAAF

A variety of aircraft were used for evacuations - Liberators and Catalinas (mainly for walking wounded) but the most reliable were the wonderful C-47s. The aircraft were fitted with metal brackets, holding 12 stretchers on each side in stacks, plus one or two walking wounded, one Sister, one Orderly and three aircrew. Sisters were responsible for loading the aircraft from the ambulances, organising each patient according to his condition. Serious cases on the lower levels; fractures on the second layer (to tie limbs up to upper bunks); those not-so-serious were on the upper bunks. Battle fatigue boys on the lower stretchers as well - they were all fairly heavily sedated. Placing was a matter of common sense and knowledge of patient's condition, altitude and length of flights.

A typical working day for an Air Evacuation Sister began at 3am; breakfast at 3.30am; as flights over New Guinea had to be before the heat of the day. Conditions over New Guinea were quite difficult because of the terrain and the quick build-up of clouds. We flew over the sea whenever possible. It was 4 or 5 hours to Biak, on the north coast of New Guinea or to Merauke on south coast of New Guinea. Overnight in Biak if the clouds came down early, or on to Merauke. Then on to Townsville, Australia where No.3 Air Evac. continued on to other capital cities. We had a medical box with drugs and dressings and an oxygen cylinder; a 2 gallon thermos of tea. The first aid box doubled as a table for sandwich-making. Some of the girls of No.1 Air Evac. were based in New Guinea. All of us bringing out battle casualties. The boys were all tired, ill and weary.

Sister Joan LOUTIT, 2nd M.A.E.T.U. (Medical Air Evacuation Unit) R.A.A.F.

Royal Australian Navy Nursing Service (RANNS)

The RANNS was formed in early 1942. Registered nurses entered with the rank of sub-lieutenant, and were required to have at least 12 months’ nursing experience. Initially, twelve nurses were chosen in Melbourne and twelve in Sydney. At its peak 56 nursing sisters were working.

RANNS nurses served in naval hospitals in Sydney and Darwin. They staffed naval sick-quarters in Brisbane and Canberra, at Townsville and Cairns, Queensland, and at Fremantle, Western Australia. Flinders Naval Depot was the posting for the Melbourne nurses, and patient numbers reached 150 at times.

Only one member of the RAANS, Sister J.E.W. Tame, was appointed to a ship. She sailed to India in the hospital ship Manunda. Navy nurses did, however, serve overseas. In April 1944 six nurses under Sister V.E. Kelly were posted to Mile Bay in New Guinea, where they ran a 40-bed ward at the RAAF hospital.

Vital accomplishment and not sex should be the measuring rod – Dr Emily Dunning Barringer, President of the American Medical Women’s Association, 1942

By the 1940s, the professional status and prospects of women doctors had improved. More hospital residency posts were available for women doctors and medical research and scientific positions included women graduates. The Army lagged behind. Only 26 women doctors served in the Australian Army Medical Corps during World War II, mostly in administrative roles. No women served overseas: in common with other occupations their work at home freed male doctors for services. Unusually, women doctors received the same pay in the services as their male equivalents, the British Medical Association in Australia insisting on equal pay.

Winifred McKenzie

Victorian doctor, Lady (Dr) Winifred MacKenzie (nee Winifred Iris Evelyn Smith), was the first woman doctor to be commissioned with the Australian Army Medical Corp.

Winifred was born on 10 April 1900 and attended high school in Melbourne. She graduated with a Bachelor of Medicine from the University of Melbourne in 1924 and, soon after, went to work for Colin MacKenzie, a Victorian orthopaedic surgeon and anatomist. She worked as his research assistant, and they were married in 1928. (Sir Colin Mackenzie is best known as the founder of the Healesville Sanctuary for native Australian animals and the Institute of Anatomy in Canberra. He was knighted in 1929.)

Major Lady Winifred MacKenzie in her office at Victoria Barracks, 15 November 1944

Reproduced courtesy Australian War Memorial

After Sir Colin’s death in 1929 Lady MacKenzie returned to work. At the outbreak of World War II, she was one of 323 female medical practitioners registered in Australia.

Eager to contribute to the war effort, Lady Mackenzie volunteered at Army Headquarters in Melbourne. She remained a volunteer for six months before she was offered a commission with the rank of Captain on 25 September 1940.

Lady MacKenzie’s appointment was a newsworthy event – reported in newspapers across the country. Journalists felt the need to stress her ‘unusual circumstances’- in particular, that she was widowed, with no children.

Women’s columns focussed on her uniform. One journalist reassured readers of Dr Mackenzie’s femininity, commenting that her flattering uniform made her ‘a trim figure’:

From recent photographs it may seem that she is a trim figure in her uniform which adapts the regulation pattern for military officers to feminine requirements and resembles that worn by women of the Royal Army Medical Service.

Captain (Lady) MacKenzie’s roles were largely administrative. She worked in Allied Land Headquarters at Victoria Barracks, maintaining records of the (male) doctors of the Royal Australian Army Medical Corp (RAAMC). She also managed the appointment of the first masseuses (physiotherapists) and provided advice on issues of women’s health. She was the first female medical officer to be promoted to the rank of Major in the Australian Army Medical Corps and was later promoted to Lieutenant Colonel. After the war Lady MacKenzie remained active in the Army Reserve. She was discharged on 31 January 1947 after seven years of service.

Japanese troops invaded Malaya (now part of Malaysia) on 8 December 1941. They swiftly advanced southwards and by late January were approaching Singapore. The Australian nurses in the region were ordered to evacuate. Seventy-two nurses embarked with hundreds of patients and civilians aboard the Empire Star and the Wah Sui. They made it to Australia, but suffered heavy bombardment on the way.

The Vyner Brooke was the last ship to leave, on 12 February 1942. It sailed south with almost 200 passengers, most of them women and children. Among the passengers were the last 65 Australian nurses in Singapore.

On 14 February, while heading for Sumatra via Banka Strait, the Vyner Brooke was attacked by several Japanese aircraft. It was crippled by several bombs and within 30 minutes rolled over and sank bow first.

The nurses survived the bombing, but 12 were either drowned before they could reach lifeboats or rafts, or swept out to sea and lost. Some of the nurses made it to Banka Island, and were taken prisoner by the Japanese.

One group of 22 nurses, some civilians and wounded men were washed ashore on Radji Beach, Banka Island. When Japanese troops arrived at the beach, they shot and bayoneted the men and ordered the Australian nurses, and one British civilian woman, to wade into the sea. As they walked into the water, Sister Esther Stewart called out: ‘Girls take it, don't squeal.’

Despite being in their nurses' uniforms, all with the Red Cross emblem on their sleeves, no mercy was shown to the women. When they were thigh-deep in water, they were shot from behind.

All but Sister Vivian Bullwinkel were killed. She was shot in the diaphragm but managed to float in the water until the soldiers left. She then crawled out of the water and into the jungle. Some 12 days later she surrendered to the Japanese. Bullwinkel spent the next three and half years in captivity in prison camps on Bangka Island and in Sumatra.

Of the original 65 nurses evacuated from Singapore on the Vyner Brooke, only 24 returned to Australia. During their internment, eight nurses died from malnutrition and other easily-treated diseases.

Among the first physiotherapists to deploy was Victorian woman, Alison McArthur Campbell. She was called up in 1940 and left Australia with the AIF for the Middle East, where she served in Egypt, Libya, Tobruk and Palestine. Her expertise was used in the Thoracic Clinic, set up to develop treatments for injured lungs.

Alison kept a diary and this entry from 1941 shows some of the conditions she faced:

4.4.41

800 patients in the hospital and coming and going all day, and a wild rush of head and facial wounds. 84 patients in ward 1 by lunchtime. Patients coming in from Derna and all the way down the coast with appalling wounds.

6.4.41

Getting patients organised to go down to Alexandria on the hospital ship. That evening told to pack, kit bag only, and ready on call to leave.

7.4.41

Did not sleep much – noise of battle, all night trucks and tanks and cars and troops moved up and down. Awoke at 6 a.m., scrap breakfast, everything packed and in hall. Every man who called at the hospital had a fresh story concerning the size and speed of the German army…

Except for one small mine sweeper the harbour was empty… At 6 .m. the patients having all been loaded, ambulances came and we drove to the wharf (i.e. all the women personnel from the hospital).

8.4.41

Spent morning loading in Tobruk harbour, as more and more patients came in. About 10:30 a.m. left the harbour. About 12 noon fouled a buoy rope and spent hours watching rope being freed…

10.4.41

Gaza. Palestine. It is hard to believe and terribly hard to realise that we have arrived here safe and well, while our men are fighting for their lives out there. After a night at sea we came into Haifa harbour.

15.4.41

Had first real bath since 18th March.

In 1944 Alison was appointed Chief Physiotherapist on the staff of the Director General of Medical Service (DGMS). She acted as liaison officer between the DGMS and all physiotherapists working in Australian general hospitals and convalescent depots. Her job also included inspecting the work of the physiotherapists employed in medical units, and management of all equipment used by army physiotherapy departments. According to historian Patsy Adam-Smith:

This appointment was the result of the growth in the use of physiotherapy among sick and wounded soldiers in this war. Women had made physiotherapy so largely their field, their numbers growing from four to 150 in the army in just over four years, and it was just recognition of their important contribution that a woman should be appointed to this post.

RAAF Nurses were first posted to Papua New Guinea in April 1942. It was exclusively male when they arrived. The nurses lived in primitive conditions under canvas outside Port Moresby.

Wings, the RAAF journal, wrote that the nurses quickly earned the respect of the soldiers:

The hospital has been changed since we have had women on the station… the nursing staff had the feminine trick of making the best of any situation. They would soon have the men digging small garden beds around the theatre, around their own tents. In a very short time there would be flowers and vegetables growing where only kunai grass had waved before.

There, women had brought an enduring quality to a temporary scene. Many men will remember so long as they live, the debt they owe these women comrades of war.

In October 1941 the first RAAF four nurses were sent to Darwin, and more were posted in the following months. Conditions were primitive:

There were several patients with dysentery, dengue and malaria and an American airman very ill with blackwater fever. We firstly attended to the patients and secondly to the washing as there was not an atom of soap to be had anywhere… It was very hot and dusty… Flies were there in millions. The keeping of food was a problem as there was only one refrigerator for hospital patients and staff… for the first few weeks, sandfly bites and minor skin conditions were troublesome.

In February 1942 the nurses found themselves in the thick of things during the Japanese raids:

As we were going to our trenches we could see high up, nine clusters each of nine planes. We were in the trenches for about half an hour when a formation flew over. They came down very low and stayed for forty minutes which seemed like two hours. The relief was wonderful when we heard the all clear. We all went to our posts and attended to quite a few minor casualties and evacuated the patients safely to the 119th AGH. After a short interval, we were back to our trenches to undergo a most awful experience.

The planes came over in perfect formation, and let us have it. The noise was terrific. A bomb exploded ten yards from our trench, and believe me, we thought our end had arrived. Although our trench was of rock formation, the vibration caused it to tremble, and the dirt and rubble fell on our backs and tin hats.

When the all clear sounded, our SMO, Squadron Leader Howle, called for Senior Sister, and was surprised when we all hopped out of our trench in good condition. Apparently, he thought we had been buried when the bomb exploded so close to our trench. We shall never forget the sight which then met our gaze. The huge hangars were burning, also the equipment store, post office and the administrative block of the hospital, dental section, X-ray and dispensary. We went back to the hospital and rescued equipment which we had packed and stored in trenches.

Later we went to our quarters to prepare a meal for the staff and medical officer and found the water and light were cut off. Our home had been strafed and there were bullet holes in our uniforms which were hanging in our rooms. Just as we were going to have a snack the alarm sounded again and the sisters were ordered on to a truck and were taken out to the bush… We stayed in the bush for two hours waiting to know our fate.

Senior Sister I.M. Smith, describing the Japanese attack on the RAAF station, cited in Patsy Adam-Smith, Australian Women at War`.

Sources

Websites:

Australian Dictionary of Biography

Books:

Adam-Smith, Patsy, Australian Women at War. The Five Mile Press Pty Ltd, Victoria, 2014.

Darian-Smith, Kate, On the Home Front. Melbourne in Wartime: 1939-1945, Second Edition, Melbourne University Press, Victoria, 2009.

Kenny, Catherine, Captives: Australian Army Nurses in Japanese Prison Camps, University of Queensland Press, St. Lucia, 1987.

McKernan, Michael, All In! Australia during the Second World War, Thomas Nelson Australia, Victoria, 1983.

Neuhaus, Susan J., and Mascall-Dare, Sharon, Not for Glory: A entury of service by medical women to the Australian Army and its Allies, Boolarong Press, Brisbane, 2014

Journal articles:

Fletcher, Angharad, Sisters behind the wire: Reappraising Australian Military Nursing and Internment in the Pacific during World War II, Medical History, 2011, 55: 419-424.

Author: Old Treasury Building

Find out more | Next page: The Australian Women's Land Army