The American ‘invasion’

When the Americans arrived in early 1942 civilian morale was at an all-time low. The Japanese advance through South-East Asia had been relentless, while the fall of Singapore in February sent shockwaves around the world. Darwin was bombed shortly afterwards and for the first time, the invasion of Australia seemed imminent. Not surprisingly, the arriving Americans were greeted as saviours as well as allies. When Supreme Commander in the Southwest Pacific General Douglas Macarthur arrived at Spencer Street Station on 21 March, he received a welcome usually reserved for royalty. Thousands lined the streets to watch his black limousine drive by en route to the Menzies Hotel in Collins Street.

Accommodating the American servicemen was quite a logistical feat. While the officers booked out all available accommodation in the city’s hotels, their men bunked down in makeshift camps in the suburbs. The largest of these, Camp Pell, was erected in Royal Park in Parkville, but others were hastily assembled at the Melbourne Cricket Ground, at Fawkner Park in South Yarra, on the Port Melbourne Football Ground and in Frankston. Soon the city was thronged with jovial groups of Americans, all intent on a good time before they journeyed north. Those whose arrival coincided with the Easter holiday weekend were to be sorely disappointed, as most of the city shut down for three days. A joke said to be circulating around the American camps at this time described Melbourne as ‘half as big as the New York Cemetery and twice as dead’! But the city soon made up for it. Melbourne’s pubs and cafes served up a steady diet of hamburgers and hot dogs, washed down with Coca Cola (and beer), while the dance halls ran into the early hours of the morning to keep the visitors entertained. Melbourne at this time was said to be the ‘best liberty port in the world’.

‘Victory Girls’

From the start of the war Victorian women had been asked to donate their time entertaining soldiers on leave and acting as ‘Victory Girls’ at dances. Now that hospitality extended to the Americans. Australians were familiar with some aspects of American culture through the cinema, but few had direct experience of the country or its people. The press and magazines like the Australian Women’s Weekly hastened to provide tips on everything from American slang to food preferences. Families were urged to invite visitors home for a meal, and it seems that many were eager to oblige. At the same time the American Army printed a guide to Australia for its troops, and produced films to send home about their experiences ‘down under’. These were invariably happy and wholesome. What they did not say was that the troops were also issued with condoms, along with stern warnings about the dangers of infection from sexually-transmitted disease. Posters in the camps warned of the dangers of seductive women, however innocent they might appear.

There was huge excitement in March 1942 when the first of the American servicemen to be stationed in Australia arrived in Melbourne. By June there were 30,000 Americans in the city and near suburbs, with pubs, cafes, cinemas and dance halls all doing a roaring trade. Melburnians embraced Coca-Cola, hamburgers and by all accounts the Yanks themselves, with great enthusiasm. With their generous pay, smart uniforms and congenial manners, the American servicemen were soon in demand as escorts, and young women flocked to the city to meet them. But others were less enthusiastic. Moralists warned of a tide of ‘immorality’ sweeping the city, while Australian servicemen resented the competition from the better-paid Americans. More than one brawl broke out on the streets between rival service groups.

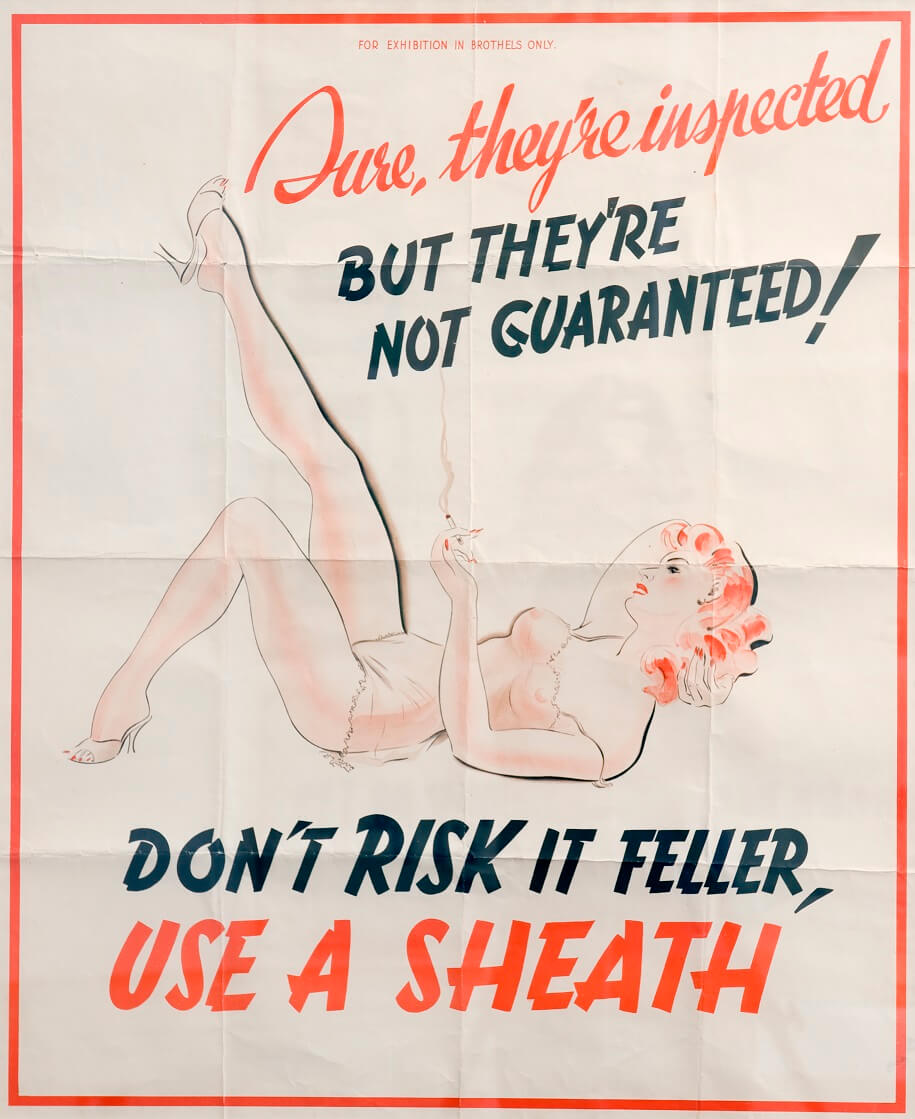

‘Don’t risk it feller’, poster, early 1940s

Reproduced courtesy City of Melbourne Art and Heritage Collection

This public health education poster – ‘FOR EXHIBITION IN BROTHELS ONLY’ – aimed to reduce the incidence of sexually transmitted diseases. Servicemen were also warned about ‘amateurs’ – young women who were not prostitutes, but were prepared to experiment with sex during the war, often for gifts and treats. There was little discussion about the men themselves spreading infection.

‘Over-paid, over-sexed and over here’!

The American visitors soon found themselves popular. They were better paid than their Australian counterparts and better dressed. American uniforms were smart, made of a superior fabric, and each soldier was provided with two uniforms, along with access to a regular laundry service. The Australian issue by contrast, was a single woollen uniform, which was seldom cleaned. The Americans were also said to be courteous escorts, polite and generous with gifts – flowers, chocolates and the highly-prized (new) ‘nylons’ (nylon stockings). It was an irresistible combination in wartime Melbourne and the Australian soldiers found they had formidable competition. Inevitably, this led to resentment. American troops were said to be ‘over-paid, over-sexed and over here’ and eventually the conflict developed into outright violence. In December 1942 a large brawl between Australians and American servicemen took place at the corner of Flinders and Elizabeth Streets, before a crowd of over 1,000 spectators. A further outbreak in February 1943 was dubbed the ‘Battle of Melbourne’ and saw mounted police called into the city for the first time in a decade. There were few casualties, but authorities in the two services invested in some determined fence-mending thereafter, hoping to restore peace and friendship.

Wartime romance

In the highly-charged atmosphere of wartime, some romances developed quickly. The first marriage between a Victorian woman and an American soldier took place in February 1942, after an acquaintance of just one week. By June more than 250 such marriages had taken place, but after this men required the permission of an officer to marry. The first Australian wife of an American serviceman travelled to the United States in May 1942, but most remained in Victoria for the duration of the war, or longer. The American Government accepted no obligation to convey these wives to America and did not offer citizenship until they had been resident for some time, leaving some women in an invidious position – literally stateless. But many were undeterred and some 12,000 marriages took place in Australia during the war years. One group of such ‘war brides and fiancées’ formed a support network and held regular meetings and social events in Melbourne. By the end of the war, many had children.

Sin city

Although Australians as a whole welcomed the arrival of the American servicemen, some disapproved strongly of what they saw as widespread immorality in Melbourne’s dance parlours, cinemas and even in the streets. Girls as young as 14 or 15 were said to be wandering the city drunk, hoping to ‘pick up’ GIs. Melbourne gained a reputation in some quarters as ‘sin city’. There was open speculation about growing numbers of ‘amateur’ women prepared to experiment with sex during these years, and an increasing sense of moral panic predicting a rising tide of venereal disease. Although the venereal disease outbreak was largely imagined, it saw some very real consequences, with increased surveillance of women in the city, and women banned from drinking in the public bars of hotels, or from purchasing alcohol in railway cafes. The drinking age was also raised to 21 (from 18) in 1942. Young, working class women were particular targets of this attempted crack-down. A special police squad was formed, equipped with a small van and unlit bicycles, to tour city parks and gardens, but the panic was relatively short-lived. By June many of the American troops had moved to the north and Melbourne returned to wartime normality. It was also a bitterly cold winter – a major deterrent for trysts in parks and gardens! The arrival of the American marines on a long spell of leave early in 1943 saw another flurry of anxiety and police stepped up their covert surveillance once again, but with little apparent success. Melbourne’s enthusiasm for the Yanks was undiminished.

There is some evidence that the war years did, indeed, present some young women with the opportunity for sexual experimentation, despite the obvious risk of an unwanted pregnancy. This might not have extended beyond heavy petting in many cases, but historians have speculated that these wartime romances may have introduced more women to the experience of sexual pleasure. One young student teacher wrote later of her ‘experience’ with her ‘Yank boyfriend’.

Anyway, I can tell my Grandchildren at least during those momentous days when Australia was rapidly accumulating thousands upon thousands of Yanks, when Melbourne went bad, and every girl discussed her ‘pick-ups’, I too had a little experience.

The ‘Brownout Strangler’

The love affair with all-things American was severely tested in May 1942 when a series of horrible murders took place in Melbourne. The first was on 3 May, when forty-year-old Ivy McLeod was found beaten and strangled, her body left in a shop entrance in Albert Park. The motive was clearly not robbery, as Ivy’s purse was still with her body. Rumours began to circulate that an American soldier had been seen in the vicinity on the night of her murder. When a second woman, Pauline Thompson, was found similarly strangled only six days later, fear gripped the city. Speculation that Melbourne was being stalked by a ‘Brownout Strangler’ was rife, as was the rumour that one of the American soldiers was responsible. Once again, Pauline was said to have been seen in the company of a young man with an American accent. Women everywhere were warned to be careful and employers began to insist that female employees be escorted to the tram or train if they were working late. Brownout regulations created a gloomy city at night– dark, shadowy and threatening – and the climate of fear was palpable.

The third and final victim was Gladys Hosking. An employee of the Chemistry Department of the University of Melbourne, Gladys was walking home through Royal Park when she was attacked and strangled. This time there were clear reports from witnesses who claimed to have seen a dishevelled American soldier in the vicinity. Then more witnesses came forward – women who had been threatened but had escaped, and the police closed in on Camp Pell. In the end Private Edward Leonski’s erratic behaviour aroused the suspicions of his tent mates, and he confessed to the murders.

Court martial and execution

In a highly unusual legal move, General MacArthur insisted that Leonski be tried by an American court martial, rather than in the Victorian courts. Although clearly disturbed, he was judged to be sane by American Army psychologists, and was found guilty on 17 July. The sentence was upheld, despite protests from Leonski’s defence attorney and two reviews, and General MacArthur signed his death warrant personally on 1 November. He was hanged at Pentridge Prison on 9 November. The Leonski case has been the subject of legal debate ever since, but almost certainly MacArthur wished to send an unequivocal message both to Victorian citizens and to his troops.

Author: Margaret Anderson

Next page: Housewives to Action!