Wise men have never doubted feminine courage, but never until this war have women of the Commonwealth been able to show that they can be as brave as men when the country needs their services. The courage and loyalty of our women are impressive and complete. There is among them a quiet, firm, steadfast resolution to play a part in bringing victory to us.

Sybil Irving, Controller of the Australian Women’s Army Service

Before World War II, nursing was the only available service role for women. But shortages of manpower and pressure from women’s lobby groups brought about a reluctant change in policy. During 1941 thousands of women joined the new women’s auxiliary services – the Women's Auxiliary Australian Air Force (WAAAF), the Women's Royal Australian Naval Service (WRANS) and the Australian Women's Army Service (AWAS). By the end of the war, more than 66,000 women had served.

Eager to ‘do their bit’

Women were impatient waiting for the Armed Services to recruit women, and from 1939 voluntary auxiliary and paramilitary organisations formed across Australia. These included the Women’s Transport Corps, Women’s Flying Club and the Women’s Emergency Signalling Corps, which trained young women in a range of communication techniques including morse code, wireless telegraphy and semaphore. (Many of these women went on to serve in the Women’s Auxiliary Australian Air Force.)

The Militors were a Melbourne organisation, set up in August 1940. Members trained in rifle shooting, first aid and military drill. Officers had military titles, and membership grew to more than 100. But despite these women’s enthusiasm, the government initially refused to make use of them.

Rewarding service

The Women's Auxiliary Australian Air Force (WAAAF) was finally formed in March 1941 after considerable lobbying by women eager to serve. Next came the Women's Royal Australian Naval Service (WRANS), in April 1941. The Australian Women's Army Service (AWAS) was the last of the women's auxiliary services to be formed in August 1941.

Initially the women served as cooks, clerks and kitchen orderlies, but with demonstrated competence (and a shortage of men), their roles changed. AWAS personnel manned anti-aircraft and coastal artillery gun sites, worked in ordnance, cipher, electrical, mechanical and intelligence units. Women in the WAAAF worked alongside the airmen. They maintained and armed aircraft, operated radars, drove trucks and instructed in drill – they did ‘everything but fly’. By 1945, 77 per cent of RAAF positions were available to women.

The jobs were equal, but the pay was not: servicewomen were paid about half a man's salary.

Aircraftwoman Alice Lovett stands with her Uncle, Private Samuel Alexander Peacock (Sam) Lovett, Melbourne, 1942.

Reproduced courtesy Australian War Memorial

In the 1940s most Australian First Nations women worked as domestic servants, with few opportunities for education or other employment. The auxiliary services offered a different path, and at least ten First Nations women are known to have served in the Australian Army, Air Force or Navy.

One of the reasons I joined the army was it was the only way I could learn

- Servicewoman, Oodgeroo Noonuccal (Kath Walker)

Government policy exempted those ‘not substantially of European descent’ from serving in the military but, by 1942, these rules were relaxed. Alice Lovett enlisted in the Women’s Auxiliary Australian Air Force (WAAAF) in 1942. The Lovett family are Gunditjmara people from Victoria’s western districts. Twenty members of the Lovett family, including two women, served Australia in both war and peacekeeping missions, from the Western Front to East Timor.

‘Army Girls must act like ladies’

A uniformed female soldier challenged clearly defined gender roles in 1940s Australia. Contradictory rumours circulated. Some felt the army would ‘masculinise’ women; others warned of the potential for ‘licentious behaviour’. Moralists cautioned: ‘a girl may be a nice girl when she goes in but she doesn’t stay nice long’.

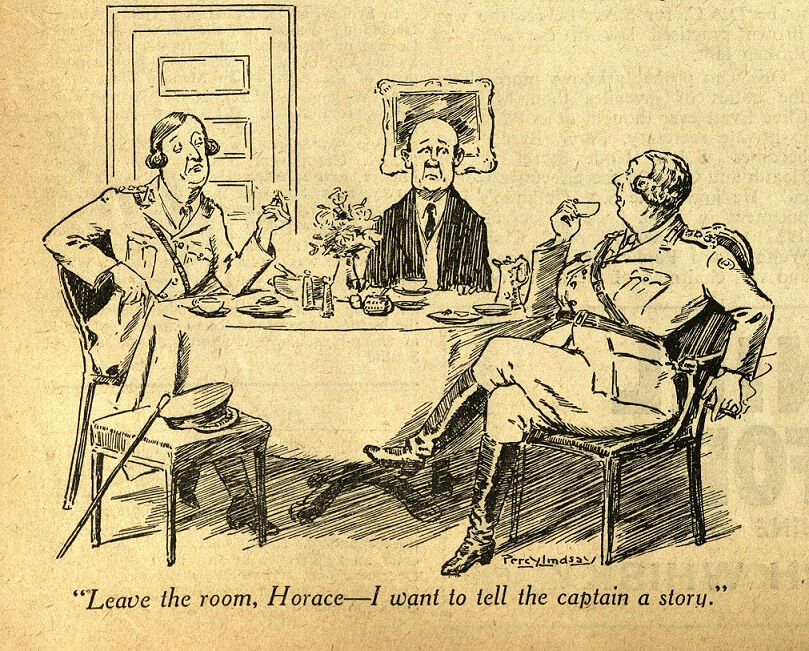

Servicewomen behaving like men! Here, the professional relationship between two women overrides the traditional marital relationship.

The Bulletin, 18 November 1942. Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

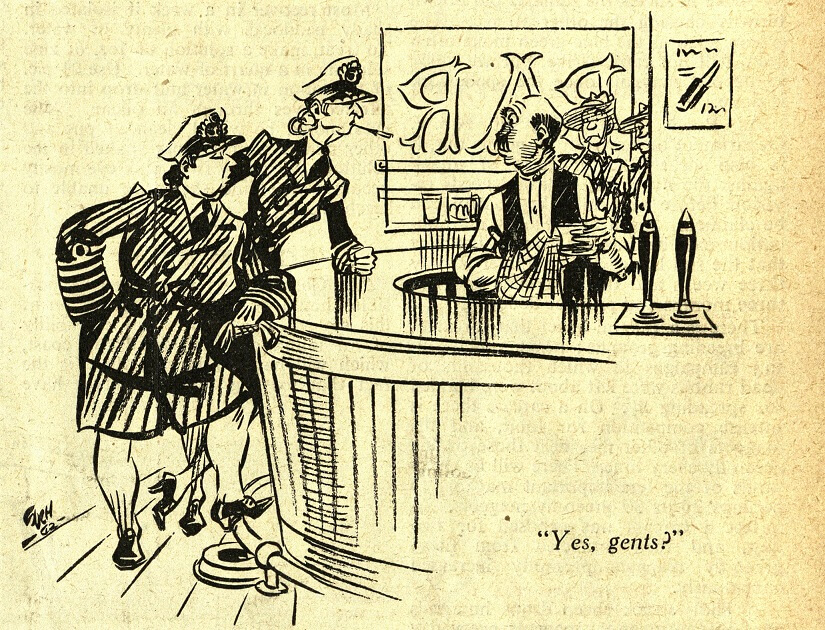

At first parts of the media focused on the potentially disruptive influence the auxiliary services might have on sexual standards. These two servicewomen are suggestive of a lesbian couple.

The Bulletin, 18 March 1942. Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

In response, recruitment posters tried to glamourise participation. There were headlines in the press - ‘Army Girls must act like ladies’ – and articles assured readers that ‘rules for ladylike behaviour in the women’s army and air force are calculated to discourage any wartime abandon’. The following notice was published in the Army Education journal, Salt:

To suggest that a year or two in barracks will detract one iota from the femininity of the Australian girl is sheer nonsense and shows a gross ignorance of her make-up. Clothes (civilian) are still the main topic of conversation after lights out … They even talk about glory boxes. Of all the girls… questioned, only 25% had thoughts of anything but immediate matrimony after the war. Nearly 50% wore engagement rings… After the war the man who meets an ex-AWAS will find her neither unduly masculine nor a harpy; he will find her as attractively feminine as any other Australian girl.

Attractive, feminine servicewomen banished the image of the ‘mannish’ woman, but may have fuelled prejudice, portraying the auxiliary recruits as sex objects and potentially ‘available’.

World War II recruitment poster to attract women to the armed services.

Reproduced courtesy Australian War Memorial

Attitudes towards the women did, however, change. According to one AWAS officer:

The soldiers saw us as playing at war. But that broke down. Women had gone into the services with such a load of enthusiasm: they’d go from dawn to next daylight. Soon officers said, “The morale and behaviour of men have lifted since women joined the Service.”

‘Thanks Girls, and Goodbye’!

All three auxiliaries were demobilised immediately after the war, with no thought to a continuing role for women. The women had access to repatriation benefits, and could march in the Anzac Day parades, but traditional ‘home-builder’ roles for women were emphasised. The exceptional work of these servicewomen was largely forgotten.

Towards equality

The role of women in the Australian Defence Force has undergone enormous change since the 1980s, resulting in a significant increase in employment opportunities for women.

Restrictions on women's service in the ADF were lifted in 2013, and barriers to combat roles were removed in 2016. Suitably-qualified female soldiers are now able to serve in the special forces and front-line combat units. Today, women comprise about 20 per cent of the armed forces.

Sources

Websites:

Australian Dictionary of Biography

Books:

Adam-Smith, Patsy, Australian Women at War. The Five Mile Press Pty Ltd, Victoria, 2014.

Damousi, Joy and Lake, Marilyn (eds.), Gender and War: Australians at War in the Twentieth Century, Cambridge University Press, Australia, 1995.

Darian-Smith, Kate, On the Home Front. Melbourne in Wartime: 1939-1945, Second Edition, Melbourne University Press, Victoria, 2009.

McKernan, Michael, All In! Australia during the Second World War, Thomas Nelson Australia, Victoria, 1983.

Scott, Jean, Girls with Grit, Allen & Unwin Australia Pty Ltd, New South Wales, 1986.

Thomson, Joyce, The WAAAF in Wartime Australia, Melbourne University Press, Victoria, 1991.

Journal Articles:

Riseman, Noah, Escaping Assimilation’s Grasp: Aboriginal women in the Australian women’s military services, Women’s History Review, published online 3 December 2014.

Author: Old Treasury Building

Find out More | Next page: Caring for the Troops