With the Australian economy on a war footing, the home became another line of defence. Housewives were urged to ‘do their bit’ by economizing wherever they could, to free up supplies for the war effort. Some level of economy resulted indirectly from rising prices early in the war years. Wartime inflation reduced consumption to an extent, but as those on the basic wage found it harder to make ends meet, government moved to maintain morale by implementing more effective price controls on food in particular – on grocery items, meat, fruit and vegetables. Otherwise life went on much as usual at first, but with the war in the Pacific came many restrictions and increasing shortages. Rationing of food, clothing and other essentials was a part of life from 1942 and housewives needed great ingenuity to manage with less.

Rationing

On the outbreak of war Britain arranged to buy the entire Australian wool clip, along with as much meat, dairy, eggs and dried fruit as Australia could send. Initially this provided a boost to a struggling agricultural sector, but prolonged drought and increasing manpower shortages soon took their toll. With the entry of the United States into the war, Australia assumed (with New Zealand) responsibility for provisioning the troops in the Pacific arena, along with its own troops elsewhere. By 1943 Australia was responsible for feeding its own population and about another two million Britons and Americans. This greatly increased the demand on food and supplies, especially as the American rations were generous. At the same time, the war in the Pacific impacted on domestic imports like rubber and tea, as well as essential agricultural supplies. With the occupation of Nauru for example, Australia lost access to the fertilizer super phosphate, with the result that crop yields fell during the war years. Some form of rationing for the civilian population was inevitable, if government was to ensure some equitable distribution of food and other essentials. Rationing was never as severe or as long-lasting as it was in Britain or even America, but it still impacted significantly on daily life. And it made the job of the housewife much more challenging.

Retail quotas

In 1939 Australia still manufactured a good deal of clothing and textiles for the local market, but on the outbreak of war many of these factories moved to uniform production. Uniforms for both the Australian and the American services were manufactured in Australia during the war years, with the result that clothing for the civilian population was soon in short supply. The government moved to limit Australian consumption by indirect means first. They imposed sales quotas on shops in an attempt to prevent hoarding, but this provoked some unseemly clashes as shoppers competed for scarce goods. Historian Kate Darian-Smith told the story of one young Melbourne woman, Val Ward, who had moved to Melbourne to work in 1943. She recalled trying to buy essential household supplies from Myers and was told that some saucepans would be released that afternoon at 2.30.

So I hung around, and I looked around, and to my surprise I saw that in the whole of that big floor where the kitchen goods were there seemed to be people hanging around everywhere, lurking in corners. I tried to see where the door to the back, behind the scenes, might be and I could see it and I thought, ‘If he comes along with some things, he’ll come along here’. There was a vacant aisle counter and I stuck myself next to this.

Suddenly I saw him come and sure enough it was half past two. He came with one of those baskets on wheels and sure enough these people started slowly converging on him, on the spot. He was ducking and he just looked so frightened – I am not surprised, because he had done it before, and I had not! – and he put all his saucepans down and ran for his life with his basket. …I was already there, and I grabbed a handle with my eyes shut and retreated.

These women fell on the table and they beat each other over the head with their handbags and so forth, trying to get at these saucepans. Finally the shouting and tumult died and people went away and paid. I’m standing with this saucepan with no lid, and on the other side is standing a woman with a lid and no saucepan. I thought, ‘I can cook with a plate over my saucepan; she can do what she likes!’ After a while, she stared me out, and stared me out, and finally she came and dumped the lid on the counter and said, ‘There, you can have it!’

I grabbed the thing, and I was as scarlet as a beetroot. I really was so embarrassed as I was always ladylike and refined in my behavior.

(In Kate Darian-Smith, On The Home Front, chap. 1)

The daily newspapers printed cartoons satirising these retail skirmishes and accusing Melbourne women of a lamentable lack of ‘self-restraint’. We are reminded of recent scenes in our own supermarkets during the early days of COVID-19.

Rationing of fuel and other essentials

Other shortages also hit the housewife hard. An acute shortage of wood from the early years of the war caused widespread hardship, especially in the bitterly cold winters of 1942 and 1943. Poorer families, who mostly cooked on wood stoves, were especially disadvantaged, but all suffered from the meagre rations, which had to be collected from local wood yards. Children were often deputised to perform this duty, using old prams, billy carts and wheelbarrows to trundle home their week’s supply. The shortage of wood caused wider inconveniences – not least an acute and persistent shortage of clothes pegs, and limited supplies of matches.

Other personal supplies were also limited. Women had to queue at chemists for their ration of sanitary pads, and could only buy one packet at a time. Rumours began to circulate that the shortage was caused in part by the Air Force, which was said to use sanitary napkins to clean their aircraft! At times ice, essential for preserving perishable goods at home, was also limited. When the ice shortage coincided with government attempts to conserve fuel by restricting deliveries of milk and meat, many expressed their frustration to the Rationing Commission.

A woman takes home her ration of firewood in an old pram, Melbourne, 1942.

Reproduced courtesy Australian War Memorial

Children, with their prams and billy carts, line up at the wood yard to buy their ration of firewood. The wood was weighed on scales. There were severe firewood shortages in Melbourne during the bitterly cold winters of 1942-43.

Reproduced courtesy Australian War Memorial

The black market

Despite hefty penalties, a black market in rationed goods flourished in Melbourne throughout the war years. The Queen Victoria Market was said to be one centre of the trade, where early morning shoppers might evade the ration queues at a price. The clothing trade was another focus for black market sales, while petrol, firewood, liquor and tobacco was also traded clandestinely. Government tried hard to suppress the trade, calling on the public to provide information, but not surprisingly, few came forward. Instead undercover police officers were used to identify some culprits. Conviction of a black market offence could result in a term of three months’ imprisonment, but most were merely fined. However there were exceptions. In September 1943 James Bonici appeared in the Fitzroy Magistrates Court charged with selling an overcoat on the black market to an undercover policewoman. In finding him guilty, Police Magistrate Mr Hammond refused to commute the three-month sentence of imprisonment, commenting: ‘Why should I suspend the sentence when this crime is so hard to detect? It is a very serious matter and upsets the rationing system’. No reference was made to Bonici’s citizenship, but if he was of Italian background, and hence an ‘enemy-alien’, this may have influenced his sentence. The sentence was subject to appeal. (Age, 10 September 1943, p. 4)

Wartime housing

A chronic shortage of housing was a serious and persistent problem throughout the war. Very few houses were built during the Great Depression and recovery was slow. At the start of the war the housing deficit was estimated at 120,000 dwellings: by 1945 it was probably closer to 350,000. As a result many Melburnians lived in shared accommodation and overcrowding was common. The outbreak of war meant that no census was conducted during the war years, but there were two sources of detailed information on the state of housing in Melbourne at this time. The first was a detailed report by Victoria’s Housing Investigation and Slum Abolition Board, published in 1937. This expressed grave concern at the state of housing in inner Melbourne in particular. It used terms like ‘congested’, ‘blighted’ and ‘decadent’ to describe much of the housing stock, including many larger houses which had fallen into disrepair, or been crudely divided into sub-lets using plywood, or even hessian, partitions. The situation was especially critical in Melbourne’s inner west, soon to be made even worse by the influx of workers to the munitions and other wartime industries located there. The Board’s inspectors conducted internal examinations of some 6,390 residences, reporting that most had no proper kitchen, one-third had no bathroom and one quarter had neither gas nor electricity. Leaking roofs, damp, poor ventilation and infestations of vermin were common. The inspectors judged that half of these residences were unfit for habitation without repair, while the other half was beyond repair altogether. They recommended a major state investment in public housing. Wartime labour restrictions and shortages of building materials meant that relatively little progress was made. A War Workers Housing Trust was created to address some of the most critical shortage of accommodation in Melbourne and Victoria’s regional towns. They built workers’ hostels and some cottages for munitions and other wartime industrial workers, but many were still forced to live in makeshift accommodation. Families lived in caravans, while others lived in converted backyard sheds and garages, or in converted railway carriages in railway sidings throughout the war. Many single people lived in rooms in boarding houses, of varying quality. All domestic construction ceased from 1942.

The Prest survey

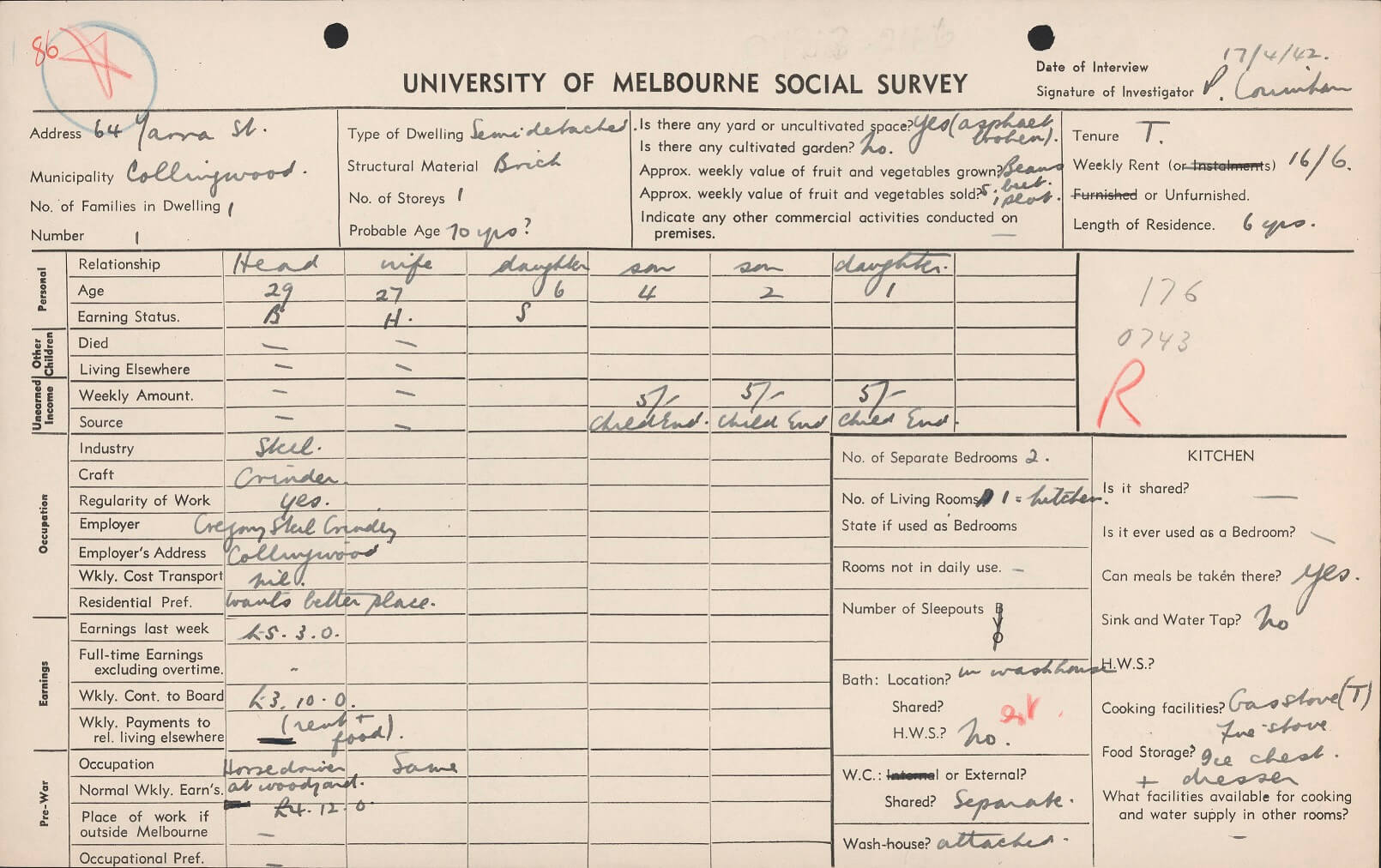

The other source of information on Melbourne’s housing stock was an extraordinary study undertaken by the Department of Post-War Reconstruction in partnership with the University of Melbourne and a group of local businessmen. It was overseen by a young economist at the university, Wilfred Prest. The Prest survey despatched young university graduates, many of them women, to interview the residents of one in 30 homes throughout Melbourne, documenting their living conditions systematically on survey cards. They followed up with a closer study of Melbourne’s inner west. In all, some 8,000 homes were documented in detail over a 17 month period in 1941-43. Householders were advised that the survey was intended to assist in ‘planning the new social order it is hoped to build after the war’, and most agreed to be interviewed, though some refused. The owners of some larger properties feared their requisition for wartime purposes, though this was not the intent of the survey.

The Prest survey confirmed the woeful state of much inner-city housing, but also revealed some startling inequalities. Kitchens and bathrooms were especially deficient. The survey found that less than half of kitchens possessed a sink, while less than 20 per cent owned a hot water service. Fully 25 per cent of homes had no internal water tap at all. In inner Collingwood the situation was even worse. There 60 per cent of household had no water tap in the kitchen, while only two per cent had hot water. Laundries in most homes in this period were either outside in a separate structure or on the back verandah and many were primitive. Wood-fired coppers were usual, and few owned washing machines of any description.

The location and amenity of bathrooms varied significantly. Most middle-class homes and newer working-class homes had bathrooms inside, but in older or poorer homes bathrooms were generally either in the yard, or on the back verandah. Sometimes bathrooms and laundries were one room and in poorer suburbs could be extremely basic. One quarter of homes still heated water for baths on a stove. Lavatories were still mostly in backyards and in poorer suburbs were often shared. Both gas and electricity was available to homes throughout Melbourne, but householders varied greatly in their capacity to use it. Some poorer homes in inner Melbourne were lit by a single bulb, often in the kitchen, while other rooms continued to be lit by candles or kerosene lamps. Less than one in ten households owned a refrigerator, with another half using an ice chest. The rest made do with a Coolgardie safe. This made daily deliveries of perishable foods and regular deliveries of ice, a necessity.

Many of the young, middle-class women who conducted the Prest survey were shocked by the living conditions they documented. Gwyneth Dow observed that she gained ‘the most impressive political education I ever had in my whole life.’ But for others it was the grim reality of life. Pat Counihan, wife of the artist Noel Counihan, was a teacher, but with the gendered pay scales in place in the teaching profession found that she could earn more conducting the surveys than she could by teaching. She was paid two shillings and sixpence per completed interview, but from this had to pay her own travel costs. Nevertheless, she managed to earn £5 per week conducting the Prest surveys – about the equivalent of the male basic wage. Since Noel was incapacitated with TB during these years, Pat was the main bread winner. One of the survey cards completed by Pat Counihan is shown below. Noel recovered from his TB and went on to become a famous artist.

University of Melbourne Social Survey card, 1942

Reproduced courtesy University of Melbourne Archives

Housework

Women at home worked hard. Very few owned any labour-saving devices, with the exception of electric irons, which were more common. But the electric washing machines that would transform washing day for the housewife were still very rare and in many respects, housework was little changed from the previous century. Wash day was still hot, heavy work, often taking an entire day, and still involved lifting heavy wet clothes from copper to tubs to rinse and then to outside lines to dry. Rugs were still mostly beaten with hand-beaters, while floors were swept, washed and polished by hand. No wonder the middle-class ladies resented government attempts to deprive them of domestic servants!

Author: Margaret Anderson

Find out More | Next page: Civil Defence