It is not too soon for the Australian Government to plan and prepare this people for a ‘scorched earth’ policy, guerrilla fighting, and all else that ‘total war’ entails.

Sydney Morning Herald, 2 January 1942

Many shop windows were boarded up, with small peep-holes in the middle. I would stop to peer at the dismal selection of austerity clothes or goods within.

Other windows criss-crossed with wide tape. Melbourne was ready for the Japanese bombers. There were hoods over the street lights which produced the ‘brownout’.

Melbourne resident, Pauline Armstrong, in Kate Darian-Smith, On the Home Front, Melbourne in Wartime: 1939-1945

In February 1942 Singapore fell to the Japanese. Only days later, Darwin was bombed. Suddenly the war was not ‘somewhere else’: it was on our doorstep, and ‘every Australian, man and woman’ was called on to support the war effort.

Ready for attack

Melbourne, with its deep-water port, munitions factories and aviation industry was a likely target. Anti-aircraft guns were installed at Maribyrnong. Prominent buildings were sandbagged or partly bricked up, and key museum treasures were removed for safe-keeping. National Emergency Services ordered the evacuation of hospitals in city centres and communal bomb shelters were built in the city and suburbs. Some suburban households built their own, with instructions published in the local papers:

The open trench in your backyard may be 4 or 5 feet deep, 4½ feet wide at the top, tapering to 3½ feet wide at the bottom. A roof of corrugated iron covered with earth and built to specifications you can obtain from your air-raid warden converts the open trench into a shelter, giving greater protection.

Thousands of women volunteered for civil defence and there was an array of civil defence groups, from paramilitary-style groups to more informal training sessions. Women volunteered as auxiliary police officers and emergency ambulance drivers. Many joined the Volunteer Air Observers Corps (VAOC), watching for enemy aircraft and shipping. The VAOC were trained in aircraft recognition and equipped with a variety of visual and audio aids, from fine optical lenses to simple bell trumpet listening cones.

Brown-out

A permanent ‘brown-out’ was introduced in Melbourne in December 1941. Streetlights were turned off, or hooded, car lights were shielded and blackout curtains hung throughout the suburbs. On 13 December 1941 the Argus announced that the dimmed lighting signified the ‘first real hint of the possibilities of war’. By January 1942:

All city lighting in Melbourne has been reduced, and transport and residents throughout the browned-out area are strictly complying with the regulations…

Only one street lamp in four is lighted, and these are shaded as to throw a dim light of not more than 40 feet in diameter. Electric trains have only two-thirds of each carriage lighted, while city and suburban stations have their ordinary lighting dimmed at least 50 per cent.

Headlights on most Melbourne trams have been fitted with hoods, both rail and tram lighting can be blacked out immediately in an emergency.

Cyclists who use their machines at night have equipped themselves with white cloths which are pinned across their shoulders, and most motorists have already fitted their cars with regulation dimmers.

A naked light which can be seen from the sea brings a penalty of £5. All electric light globes outside a house must be removed under the regulations in Victoria.

Air raid drills were common, with women appointed Air Raid Precautions (ARP) wardens. The wardens carried gas masks, helmets, and rattles or whistles. Their main duty was to patrol blacked-out streets, ensuring that no lights could alert the enemy. By early 1942 more than 60,000 people had carried out Air Raid Precautions duties voluntarily.

All states issued air raid precautions and official advice included:

Keep your head down when in an open trench. Upturned faces draw enemy fire. To avoid concussion, never lean against the walls of the trench.

Fill your bath with water when there is possibility of a raid. Have as much water available as possible, in sinks, basins, and other receptacles. A bomb may cut off water supplies, and a good supply of water for your stirrup pump may put out an incendiary bomb that might otherwise destroy your home. Also, you might be short of drinking water after an air raid.

Cover all food. Plates will protect the contents of basins against flying splinters of glass. Food in airtight tins or jars is protected against gas.

Turn off the gas meter and electricity at meter switch before going to your shelter.

Keep in readiness by your bedside a torch, a candle with matches, some money, a warm sweater, and a pair of slacks. In the case have a roll of bandages, cotton wool, drinking water, sticking plaster, a bottle of iodine, some cakes of plain chocolate, a pair of low-heeled shoes and a change of clothes. Slacks are sensible for women in shelters.

Brownout restrictions had considerable impact on civilian lives. Shops closed by 6 pm, cinema hours were staggered and public transport was delayed. In Melbourne even the trams were unlit and the Tramways Board issued conductors with special bags fitted with an interior light to prevent ‘dud’ coins from being passed in the dark. Victorian railways also removed the names of all stations in case of invasion, forcing travellers to count stations carefully after dark.

Traffic accidents multiplied. In May 1942 it was reported that four men had been killed and over 20 people injured in brown-out traffic accidents in just three hours. The Gippsland Times reported: ‘A large number of persons… have fallen down over uneven footpaths or gutters, not having been able to see their way.’

All hands to the cause

Women were eager to ‘do their bit’. They wove camouflage nets, attended first-aid classes, and mothers practised air-raid responses with their children. Even the fashion industry participated, warning against wearing high heels in an emergency. They recommended:

‘smart and serviceable’ slacks, or the new Siren Suit, consisting of a matching jacket and slacks, with no trimmings, and available in the fashionable colour of ‘Alert Brown’.

School children got involved. Schools conducted air-raid practice with pupils crouching under their desks. If caught outside, ‘the drill was to lie as flat as we could in the gutter, and bite on our cork or peg to minimise injury from flying shrapnel and avoid biting through our tongues when bombs exploded near us!’

The crisis passes

By late 1943 the threat of invasion had passed, and the appeal of civil defence faded. Bomb shelters filled with muddy water, becoming a breeding ground for mosquitoes and a hazard for small children. Civil defence organisations were slowly disbanded.

‘Not For All, Dig One Yourself!’

Trenches, surface and underground shelters were constructed throughout the city and suburbs.

Civilians were encouraged to build their own backyard trenches to shelter in. Some families built elaborate concrete bunkers but more often, shallow trenches were dug and covered with whatever was at hand. Many simply huddled under the kitchen table when the air raid siren sounded.

[masterslider id="6"]

When the lights were off

From December 1941 Melbourne was ‘blacked out’ – all street lights were turned off, or hooded, and all windows were covered.

ARP wardens insisted on strict compliance with the blackout regulations: householders were required to cover their windows so that absolutely no light could be seen. A typical family home could be ‘blacked out’ by a handyman with blinds and battens in two nights for a cost of about £1 1s. Many women just used blankets, attaching them each evening at dusk.

By May 1942, restrictions were relaxed. The Age reported:

Public and street lighting will be restored… To-day the brown-out will exist only in areas within ten miles of the coastline. The Premier’s order suspends the brown-out on vehicular and private lighting in other areas until such time as it is deemed necessary to reintroduce it, or on the sounding of an air-raid warning signal.

Across Melbourne women prepared for the nightly ‘brown-outs’. ARP wardens patrolled the suburbs, particularly during Air Raid Drills when the sirens would sound.

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Patients of Prince Henry's hospital watch ward windows being prepared for blackout.

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Women’s work

Many organisations, largely made up of women, took on the boring and repetitive task of making camouflage nets. Women estimated that they required eight hours to complete one net.

The Country Women’s Association in Victoria organised net-making groups all over the state: men, women and children, old and young, in country and town, gave up their time to help.

All sorts of camouflage nets were made: large ones to cover gun emplacements, smaller machine gun nets, nets to cover aeroplanes, as well as 12,000 aerial supply nets for the dropping of medical supplies, food and equipment for front-line troops. Over 150,000 camouflage nets were made by the CWA.

Voluntary workers, Mrs J.E. Earl and Mrs Wood, making camouflage nets, Melbourne, c.1942

Reproduced courtesy Australian War Memorial

Mass production of camouflage nets, Melbourne, c.1942

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Two women, members of General Motors Holden's staff, voluntarily making camouflage nets.

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

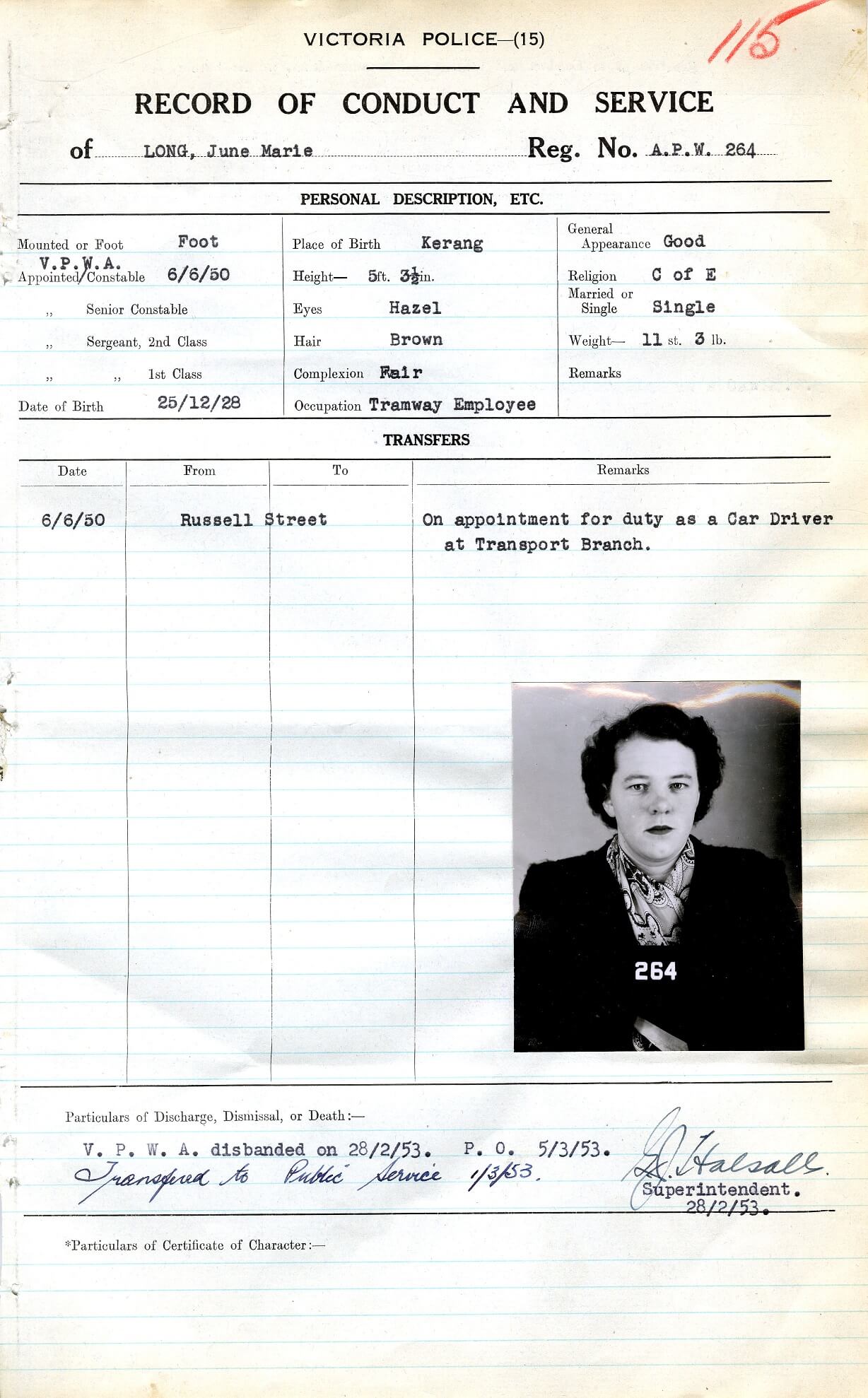

Police women

More than 200 women served in the Women’s Police Auxiliary during World War II. They worked as drivers, licence testers, lift attendants, receptionists, switchboard operators, clerks and typists.

Unlike other women’s auxiliary services, the Women’s Police Auxiliary remained after the war, continuing until February 1953. The 48 women remaining as members were discharged at this time. Some joined the ‘regular force’, serving as members of the Victorian Police.

Swearing in of auxiliary police members, Russell Street police headquarters, 1942

Reproduced courtesy Victorian Police Museum

June Long served as a member of the Women’s Police Auxiliary Force for four years as a driver. She became a sworn member of the Victoria Police in 1954.

June Long and her colleague Enid Gollop were the first female officers to work in Bendigo when stationed there in 1957. She remained in Bendigo until she retired in 1980.

Reproduced courtesy Victoria Police Museum

Sources

Websites:

Books:

Adam-Smith, Patsy, Australian Women at War. The Five Mile Press Pty Ltd, Victoria, 2014.

Darian-Smith, Kate, On the Home Front. Melbourne in Wartime: 1939-1945, Second Edition, Melbourne University Press, Victoria, 2009.

McKernan, Michael, All In! Australia during the Second World War, Thomas Nelson Australia, Victoria, 1983

Author: Old Treasury Building

Next page: Women in the Armed Services