Navigation

Women in the paid workforce

The Question of Equal Pay

Volunteering for Victory

The Yanks are Coming!

Housewives to Action!

Civil Defence

Women in the Armed Services

Caring for the Troops

Australian Womens Land Army

A Women’s world in post-war Victoria

Peace at last

Jubilant rejoicing greeted the long-anticipated end of the war in the Pacific, announced on 15 August 1945. Victory in Europe (VE) Day on 8 May had marked the official end to hostilities in Europe and the surrender of Germany, but it was to be another three long months of fighting in the Pacific theatre before Japan finally surrendered and Australia could be at peace. The American decision to drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki forced capitulation. Australians were horrified at the destruction wrought by the bombs, but welcomed the end of the war. As Prime Minister Ben Chifley announced the end of hostilities on ABC radio at 9.30 am, crowds gathered spontaneously on the streets of Melbourne, dancing and cheering in front of Flinders Street Station and the Town Hall. Victory in the Pacific, VP Day, was declared a public holiday throughout Australia.

Celebrating Victory in the Pacific (VP Day) in Melbourne, 15 August 1945

Reproduced courtesy Australian War Memorial

Three friends from the Kodak Abbotsford Factory were amongst the crowds in Melbourne on that day. Lois Anne Martin, shown in the centre of this photograph, had knitted a special ‘victory vest’ in anticipation of the celebrations and wore it proudly. She also painted her face with the letters ‘VP’ and her delight and relief are clear to see. The vest was worn only once, on this day, and was later donated to the collection of the Australian War Memorial. Her friends were (L-R) Betty Williams and (possibly) Carmel O’Connor. Lois Anne Martin married former serviceman William James Drew in 1946, but we know nothing of her life after that.

Three workmates celebrate VP Day in Melbourne, 15 August 1945

Reproduced courtesy Australian War Memorial

The wait continued

Although the war was over, the waiting was not. The families of the thousands of servicemen and women held by the Japanese in brutal conditions as prisoners of war faced a long and anxious wait to learn their fate. Some camps were not liberated until mid-September. All of the POWs who returned required long periods of recuperation and care and many died young.

Sisters Jenny Greer and Betty Jeffrey (right) recovering in hospital in 1945 after their release from Japanese POW camps. Betty weighed just 32 kilograms.

Reproduced courtesy Australian War Memorial

Post-war reconstruction

Once the victory party was over, the serious business of demobilization and dismantling of the wartime economy began. Women were some of the first casualties in this post-war economy, expected to make way for returning servicemen, as John Curtin had promised in 1941. Marriage and the ‘Australian dream’ of a home in the suburbs were to be the new focus of their ambition.

The Australian government’s vision for the post-war nation was ambitious – nothing short of ‘jobs and rising living standards for all’, as Ben Chifley announced at war’s end. In fact planning for post-war reconstruction had begun early in the war, overseen by a remarkable group of public servants led by Herbert Cole (Nugget) Coombs (1906-1997). Coombs was a young Keynsian economist, with a commitment to ensuring prosperity through full employment. His department also pursued a vigorous housing policy, with the aim of providing social housing for all of those in need. It was a humane vision for a better future after years of anxiety, loss and privation. But for all its commitment to a more equal society, this was a gendered vision. ‘Full’ employment, meant full employment for men: it was assumed that ‘Mrs Australia’s’ prosperity would be provided by her man, while she sought fulfilment in her marriage and her home. Many women did just that. Inevitably after six long years of war, there was a marriage boom as the men returned home, and then a ‘baby boom’ shortly thereafter. This demographic spike was pronounced enough to coin a term for the generation born immediately after the war and during the long economic boom that followed – the ‘baby boomers,’ defined as those born between 1946 and 1964. They would experience one of the longest periods of peaceful economic expansion in Australia’s history and it was their memories of full employment and unprecedented levels of home ownership that defined the ‘Australian dream’ for the rest of the twentieth century.

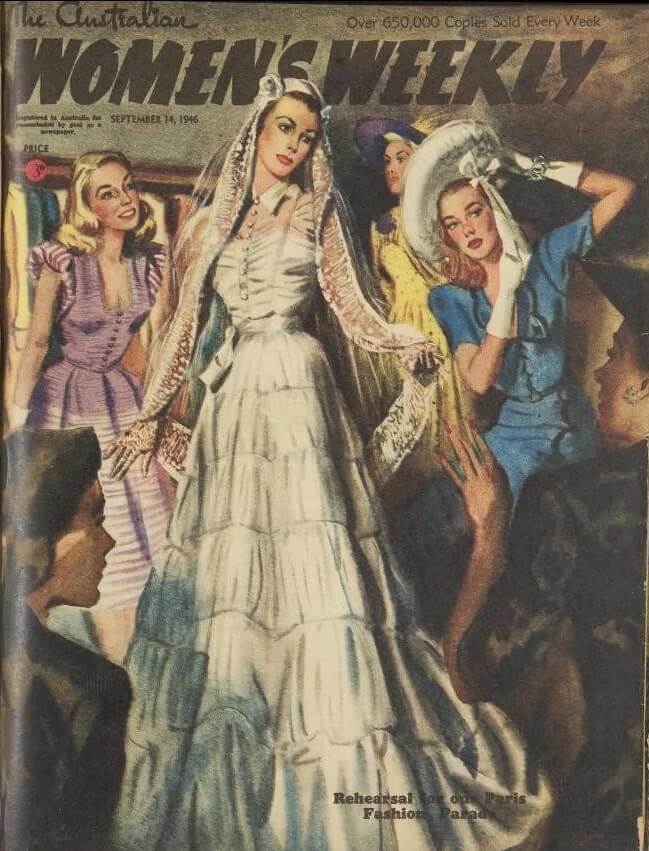

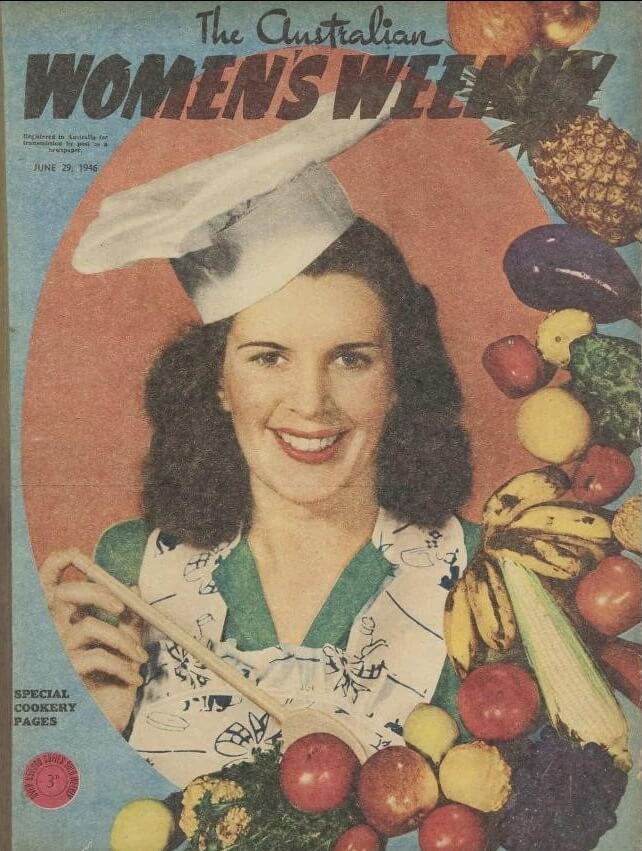

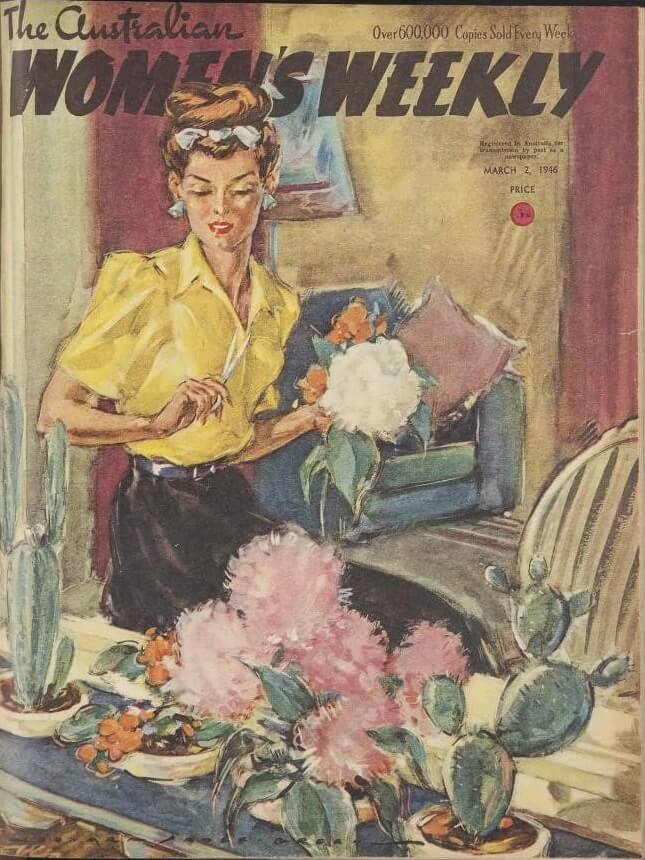

‘Mrs Australia’

The image of woman as homemaker and mother was promoted relentlessly from the end of the war. Newspapers and magazines that during hostilities had supported working women, and encouraged women to move into men’s jobs to help the war effort, switched overnight to present women almost exclusively in domestic roles. A woman was either married, or hoping to be married, while girls were in training for their later lives as wives and mothers. Femininity, fashion, grooming and sexual attractiveness dominated women’s magazines, along with articles on housekeeping and cooking. Magazines like the Australian Women’s Weekly, which had expanded its readership significantly during the war, was ready for the peace with bridal fashions, patterns and advice. It also printed regular features on cooking, including recipes, and in time began to publish cookery books that became best sellers. In the immediate post-war period features on home design were also popular.

Australian Women’s Weekly cover, 14 September 1946.

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Bridal fashions in the post-war period were already moving away from the economical styles of wartime rationing.

The Australian Women’s Weekly cover, 29 May 1948

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Australian Women’s Weekly cover, 29 June 1946.

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Cookery was soon to become a lucrative market for the Weekly.

Australian Women’s Weekly cover, 2 March 1946.

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

‘Mrs Australia’ in her modern home.

Wives and mothers

In the post-war period women were bombarded with idealized images of family life. Advertisements for products from kitchen materials to new appliances presented perfectly-groomed, smiling women, usually with children – all perfectly behaved. Some examples are shown below. The advertisement for Masonite, a new building product, is typical of many. It reflects the post-war preoccupation with homemaking and with do-it-yourself building tasks. While the men do the carpentry, the glamorous wife in her spotless kitchen cooks for her two well-behaved children.

Advertisement for Masonite, The Australian Women’s Weekly, 8 January 1949

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Populate or perish

Despite the baby boom, the Australian Government hoped to persuade women to have still more children. Australia’s wide open spaces and long, sparsely-settled coastline seemed to leave the country vulnerable to the threat of invasion and it was believed that the country needed a larger population to make it secure. But most Australian women were not interested in large families and the ‘average’ family hovered between two and three children throughout the 1950s. Government turned instead to immigration, hoping to attract British migrants in the first instance. When this failed to provide sufficient numbers of potential immigrants, they turned their attention to the many thousands of refugees still housed in camps in Europe.

Advertisers also saw value in depicting large families and in the 1950s Unilever, manufacturer of the popular laundry detergent Rinso, created a series of advertisements featuring such families. Ideal families were exclusively heterosexual at this time. No hint of alternate sexuality entered this discourse. Homosexual activity was illegal and was suppressed.

The home beautiful

It was one thing to promise ‘Mrs Australia’ a dream home in the suburbs, quite another to provide it. In the immediate post-war period and well into the 1950s there was an acute shortage of both housing and building materials, while strict regulations controlled house size and building products. Many families were forced to share houses with relatives, often parents, while others rented backyard ‘studios’, or even garden sheds. Many of those waiting for social housing found temporary homes in former army camps, including Camp Pell in Carlton, or in disused railway carriages. Conditions in the camps were far from the ideal of post-war Australia.

Not surprisingly, there was strong public interest in house design and in do-it-yourself building projects. Partly to meet this need, and to provide a service for those on limited budgets, the Royal Institute of Architects created the Small Homes Service, which it ran out of the Myer Department Store. The service offered prospective home owners affordable advice and access to cheap, architecturally-designed house plans. The plans reflected modernist design principles, aiming to maximize use of space, and were strongly influenced by the eminent architect Robin Boyd. Many prospective home builders made use of them. Home ownership was a powerful component of the ‘Australian dream’ and by 1966, after two decades of full employment, 72 per cent of Australian families were buying their own homes. The building trade was also an important employer in Australia at this time and itself contributed to achieving full employment during this period.

Brochure featuring a range of ‘Small Homes’ available, 1959

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Domestic bliss?

Creating the ‘home beautiful’ was a lot of work. Many household tasks had changed very little since the previous century and the highly-desired, labour-saving appliances of the advertisements were still beyond the means of most ordinary housewives. The household wash could still take most of one day and generally still involved boiling clothes in a copper, before lifting heavy wet clothes in and out of rinsing tubs. It was hot, heavy work and especially unpleasant in the summer. Domestic assistance had also vanished in all but the wealthiest households, leaving ‘Mrs Australia’ to do the work herself.

At the top of the list of desirable household appliances was the refrigerator and many families made this their first major purchase. Washing machines took longer to reach the majority of homes, while the newest invention, the ‘fully automatic washing machine’ remained a dream until well into the 1960s for most families. However, the whitegoods manufacturing industry was expanding fast, with local manufacturers taking advantage of protective tariffs to build their markets. Growing numbers of women, many of them recent migrants, found employment on their assembly lines and ‘Mrs Australia’ took advantage of expanding time payment arrangements.

Advertisement for a Simpson fully automatic washing machine, 1957

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

These were the ‘top-of-the-range’ machines in 1957, but most women had to be content with the models shown below – variants of the machines with hand-operated wringers attached, and designed to run alongside the older system of rinsing troughs. Home laundries often had a system of three troughs for rinsing, the last trough containing the ‘blue’ rinse water to whiten the wash.

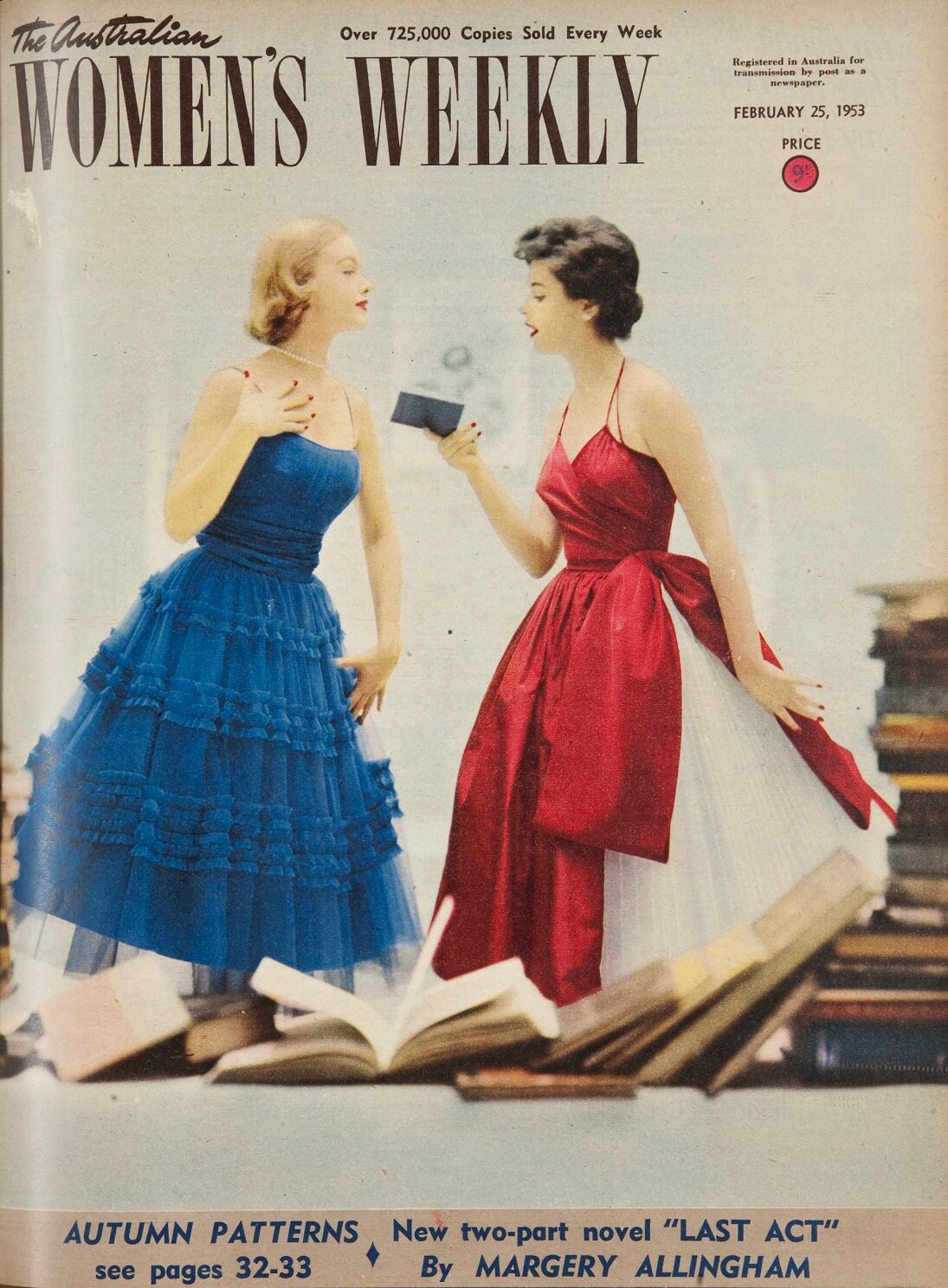

Post-war fashion

As wartime restrictions gradually loosened, the fashion industry celebrated with exuberant new styles in women’s dress. Although rationing of clothing and fabrics continued, until March 1949 in Britain and July 1950 in Australia, Christian Dior’s celebrated ‘new look’, launched in Paris in February 1947, set the trend for the decade. With its fitted bodice, tight waist and full skirt, the ‘new look’ cast austerity aside to celebrate the female form. Other fashion houses followed suit, and women’s magazines were soon filled with illustrations and dressmaking patterns for those with skill at the sewing machine. It was a style reminiscent of the crinoline of the previous century and indeed the full skirts were often supported by especially-stiffened petticoats.

Many Victorian women found fashion tips in the Australian Women’s Weekly, where regular features provided seasonal information. The celebrated Royal tour of South Africa in February 1947 was reported in detail, with a special feature illustrating in colour a selection of the gowns made for the Queen and princesses. Although obviously made in advance of Dior’s famous launch, these gowns by Norman Hartnell and other British designers, anticipated some of the elements of the ‘new look’, with their flared skirts and fitted waistlines. Other dresses were more reminiscent of recent wartime styling. Hartnell went on to design Princess Elizabeth’s wedding dress

Australian Women’s Weekly, 8 March 1947.

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Although ordinary women could not aspire to the glamour of a Dior or Hartnell creation, they adopted the main stylistic elements of the ‘new look’ with enthusiasm.

An unidentified mother and her children dressed for a Sunday walk, Biggest Family Album.

Reproduced courtesy Museum Victoria

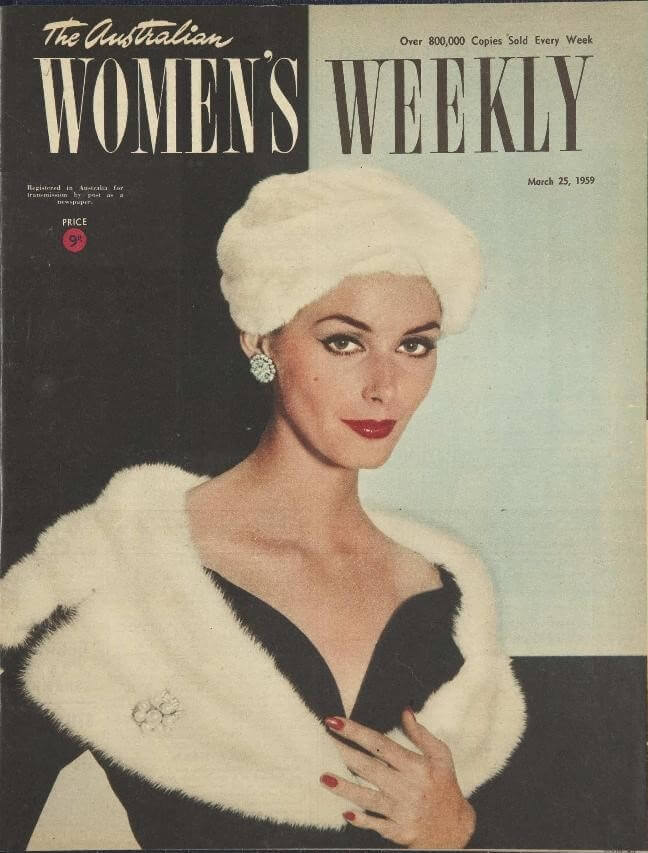

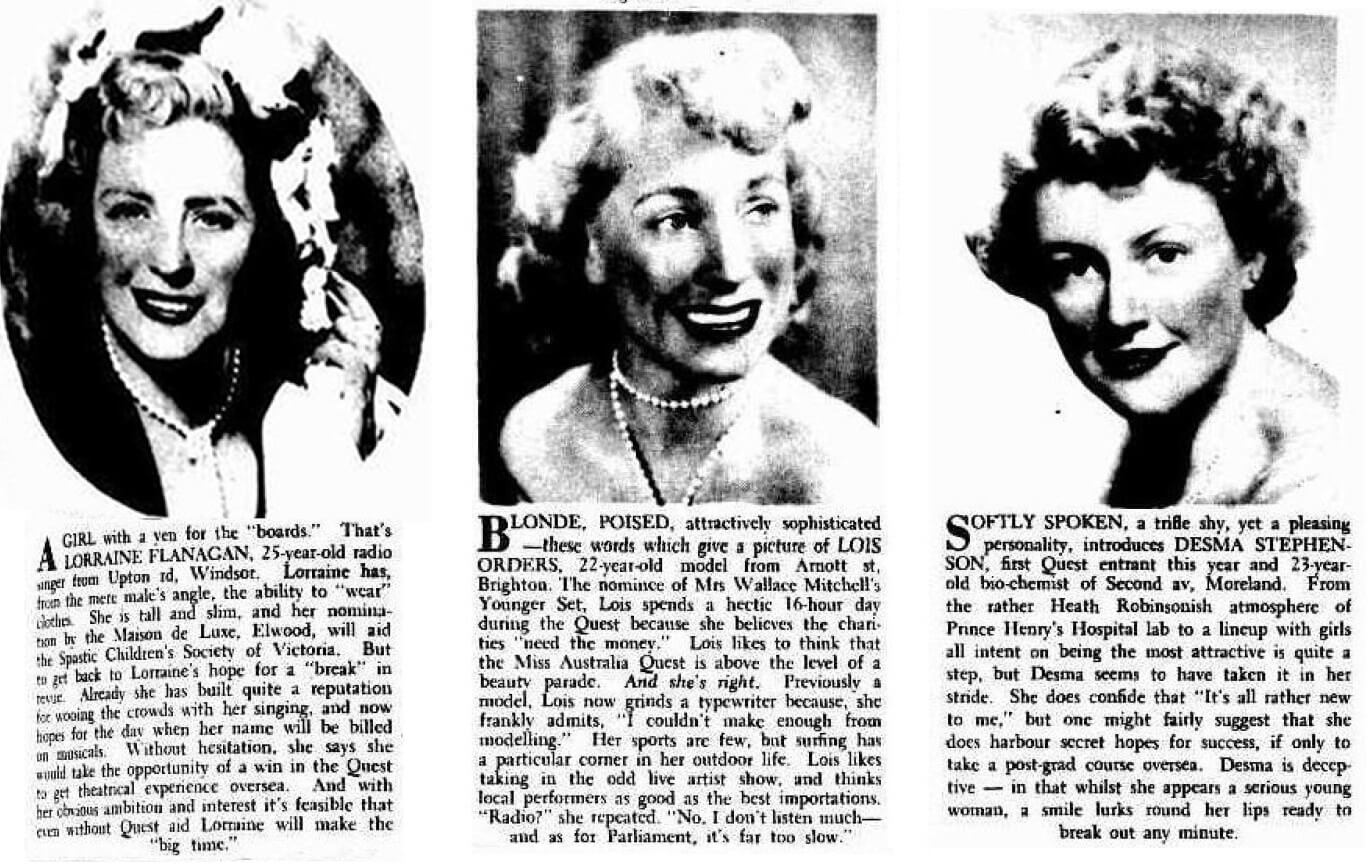

Femininity and sexuality

An emphasis on femininity was not a new development: it was a preoccupation of the war years as well. But the post-war period saw an increasing emphasis on women’s sexuality and women’ sexualized bodies dominated advertising to a growing extent. The plus side of this was that women’s right to sexual pleasure in marriage was acknowledged, although not yet outside marriage: the down side was that women were characterized increasingly as sexual beings above all else. Popular beauty contests drove home the message, even on university campuses. The beauty contest reigned supreme until it was challenged by the Women’s Liberation Movement of the 1970s.

Australian Women’s Weekly cover, 25 March 1959.

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

In images like this the line between ‘glamour’ and sex appeal was blurred.

‘Miss Victoria’ 1947 The Argus 29 October 1947.

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Beauty contests generally involved contestants parading before (all male) judges in a variety of outfits, including bathing costumes.

‘Miss Victoria’ beauty queen competitors, The Argus 5 November 1949.

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Further reading

Joy Damousi & Marilyn Lake (eds) Gender and War: Australians at war in the twentieth century, Cambridge University Press, 1995

Patricia Grimshaw et al, Creating a Nation 1788-1990, McPhee Gribble, 1994

Stuart Macintyre, Australia’s Boldest Experiment: war and reconstruction in the 1940s, New South, 2015

Susan Sheridan, Who Was That Woman?: The Australian Women’s Weekly in the Postwar Years, University of NSW Press, 2001.

Author: Margaret Anderson