It is expedient at all times to remember that a war can be lost on the food front.

Wallace Wurth, National Director-General of Manpower, May 1942

Having seen the value of Women’s work in England I feel you will now be able to give the Women of Australia a more definite lead in our work, and in connection with a Women’s Land Army I would welcome any help the Government could give. A shortage of male labour is already very apparent in many parts of the country and I have been appealed to for women to fill the gap.

Ada Beveridge, the Executive Chairman and Director of the WRANS Land Section, to Prime Minister Menzies, May 1941

Young women from all walks of life responded to the call. Many were city girls with virtually no previous experience of life and work on the land. The response and attitude was magnificent, particularly as there was no glamour being offered with the job; they were volunteering to help replace the ‘sons of the land’. All that was being offered was hard work and long hours, but with this, the opportunity of making a worthwhile contribution to the war effort.

Their working uniform was bib-and-brace overalls, which they donned with pride. They were not afraid to ‘get a little dirt on their hands’ while working side by side with the farmers whose sons were away. Chores like driving horses, milking cows, harvesting, picking grapes, hay-making, repairing fences, work in the shearing shed and lamb-marking must have seemed a far cry from the life these girls had led before joining the AWLA. To those uninitiated young women the work at times must have been arduous and backbreaking, but the cheerful attitude never faltered.

I can write all this with authenticity because my place on a property was taken by one such member of the AWLA while I was away. On my establishment there remained my father and mother and bride wife to manage the property. A call for help was made to the AWLA and without the wonderful response from that volunteer member I do not know how those left behind could have managed.

Mr Allan Forrest, son of a farmer at Springton, South Australia, speaking about ‘Land Girl’ Audrey Lynch, who worked at his family’s farm during the Second World War.

By 1942 Australia’s farmers were struggling. The countryside emptied as young men enlisted, and there was a severe drought. Australia’s rural industry needed to provision both its own people and the Allied forces in the Pacific, while also sending food to Britain. Lobbying to establish a national women’s land army increased, despite government scepticism. Finally, in July 1942, the Australian Women’s Land Army (AWLA) was formed.

Administration of the scheme

From 1939 voluntary ‘land armies’ began to take shape around the country. In New South Wales, the Women's Agricultural Security Production Service (WASPS) assisted with harvesting local crops. The Women’s Auxiliary Transport Service in Queensland directed some of its members to land work and in Victoria, the Country Women's Association Land Army (CWALA) was formed. Established as a national organisation on 27 July 1942, the Australian Women’s Land Army united these groups under the jurisdiction of the Director-General of Manpower.

A Superintendent of the Land Army was appointed in each state. They supervised the selection, enrolment, discipline and welfare of members. There were two divisions: full time members and auxiliary members. Full time members enrolled for continuous service for 12 months (with the option of renewal). These members received badges, a uniform, working clothes and equipment. Auxiliary members worked for short periods only, during seasonal rural operations. They received a badge, working clothes and essential equipment on loan.

The AWLA was a voluntary group, not an enlisted service. The women were paid by the farmer but earned much less than the men they replaced. They worked an average of 48 hours per week and received a minimum of 30s per week, plus keep. This was about two-thirds of the male minimum wage at the time.

AWLA headquarters provided some training in farming skills for women and then organised their employment on rural properties. Training establishments were set up in Victoria, Queensland, Western Australia and Tasmania. Recruits had to be between 18 and 50 years of age and be British subjects.

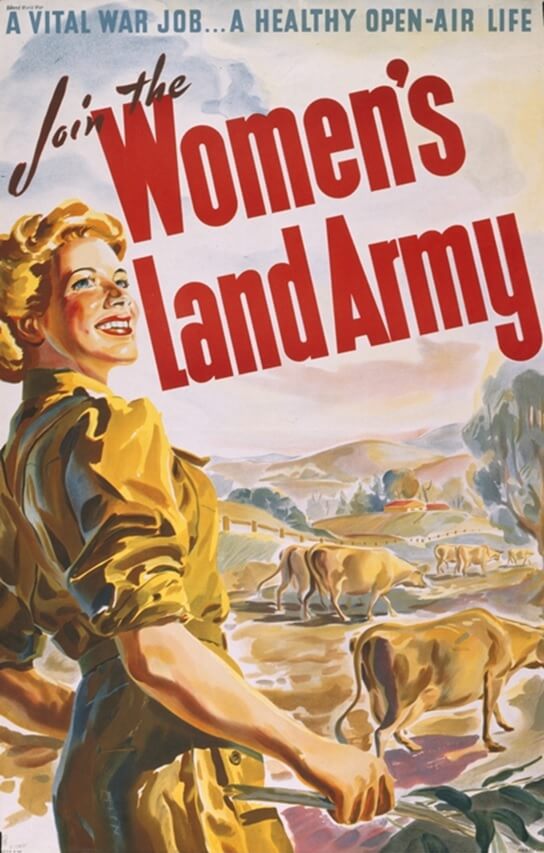

Land Army recruitment poster, 1943

Reproduced courtesy Australian War Memorial

Women were eager to join the armed services, but the AWLA had less appeal. In an attempt to boost recruitment, government produced colourful posters showing peaceful rural scenes and featuring attractive young women. But these promotional campaigns had little impact and the Land Army remained the ‘poor relation’ of the women’s auxiliary services.

Most recruits to the AWLA were unfamiliar with the rigours of farm life and work. According to one land girl: ‘The country girls were much too wise, they knew how hard the work was, they all went and joined the WAAAF and the AWAS'.

Life on the land

The Land Army girls were engaged in all types of rural work - in the fruit, vegetable, dairy, flax, tobacco and cotton industries, in mixed farming, in poultry raising and in pastoral industries. Some members worked in associated industries, such as fruit packing and grading, and wool classing. In Victoria a number of women were qualified as certified herd testers and were assigned to this work. They were trained at Burnley Horticultural School: 24 Victorian girls and one from South Australia attended the tarining and all passed. These girls lived nomadically, travelling from dairy to dairy. It was important work as Australia was, at this time, losing thousands of pounds worth of valuable stock through the spread of mastitis.

Known as ‘land girls’, no job was too hard: post holes were dug, drains cleared, and dead animals and night soil were buried, in the heat of summer and icy winter. Victorian land girl Merle ‘Mickey’ Slattery (nee Goode) remembers the many different tasks she was assigned:

Garfield: asparagus, the rapid growth and the warm earth beneath our bare feet or sic?. The fun of tent life; aching backs and the snacks.

Lysterfield: vegetables, cutting, bagging and weeding. Poor accommodation and we were treated as peasants. Withdrawn by HQ, thank heavens!

Lake Bolac: flax; wind, wind, wind; dry flax, wet flax, frosty flax and more dry flax…

Mont Park: milking, which I found impossible to learn. My shrieks left the shed in chaos; I departed within the week.

Many of the women came from the cities, with little knowledge of the land. One land girl, Jean Scott, reflected on the hazards of rural life:

Insects and vermin were there at all times: March flies, sandflies, mosquitos, stinging wasps and the ubiquitous fly. Spiders and centipedes were simply squashed once the girls overcame their fright, while goannas, lizards and snakes had to be dispatched with a hoe or a spade; nesting magpies dive-bombed the girls from the nearby trees and fruit bats blundered into them at night as they made their way to the latrines.

Conceived in haste, the program’s organisation was poor. One farmer wrote to the Director General of Manpower in 1943: ‘some girls are so short of footwear that they are working in their slippers’. Beryl Price, who joined up at the age of seventeen, remembered the lack of preparation:

I was very excited. I went off on my own on the train... The train was 'packed' with everyone in some kind of uniform. I did not have any issue of clothing from the AWLA… We weren't issued with any clothes for weeks, only a box of washed used Army pants, some overalls, and an old Army hat to use.

Toiletries and other basic needs were purchased by the women. Some women claimed their wage did not cover expenses and they finished with less money than when they joined.

Victorian ‘Land Girl’, Dorothy Arrowsmith, milking a cow.

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

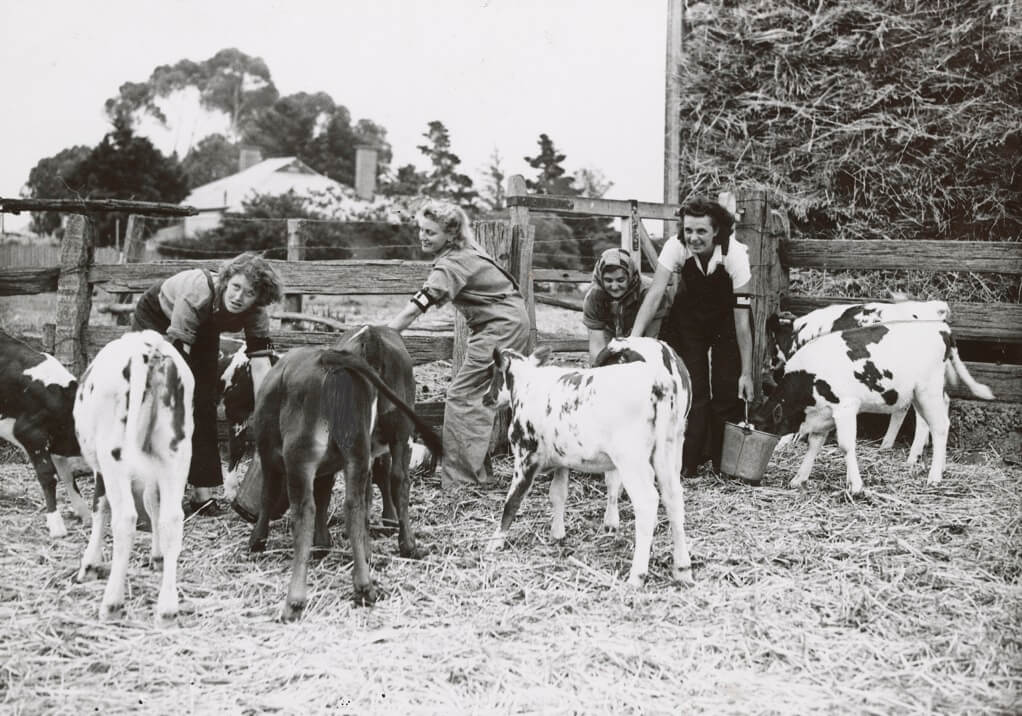

‘Land Girls’ feeding calves.

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

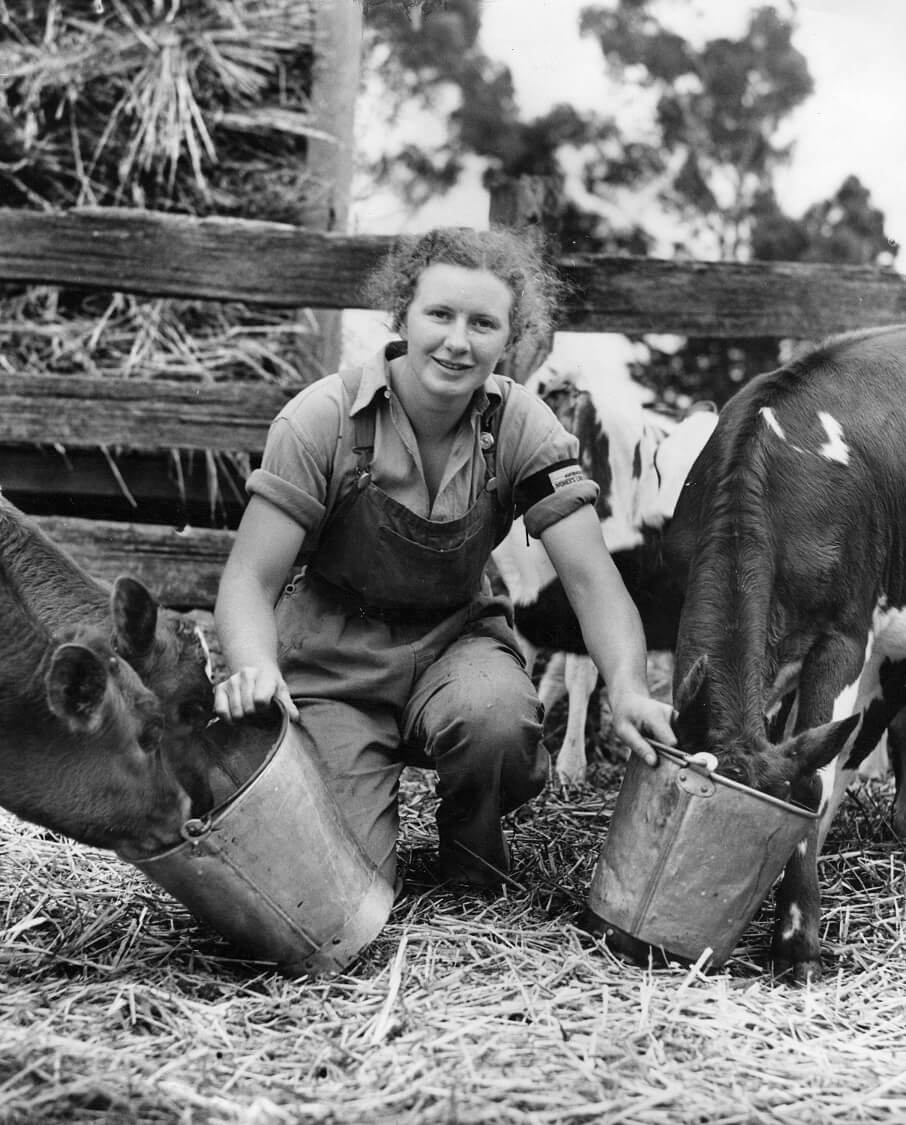

Margaret Dickson feeding calves.

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

The land girls on dairy farms worked hard, starting at 4am with milking. They fed calves, cleaned yards, lugged cans of milk and often transported the milk by dray to the depot. Hand milking was slow and often painful with recalcitrant cows.

Despite the isolation and physical rigours, most women relished the fellowship of the AWLA and their contribution to the war effort.

This video features original footage of land girls picking peaches and the reminiscences of Eileen Baget.

Thanks Girls and Goodbye, running time 3:40 minutes

Courtesy Film Art Media

Living arrangements

Hotels, boarding houses, showground buildings and public halls were occupied as camps, and hostels were established across the state. Some of the land girls were billeted on private farms. The lucky ones were welcomed, but a few encountered suspicion and sometimes harassment:

They encountered suspicioun and jealousy from a few farmers’ wives, rank dislike from some of the local girls because the young fellows of the district showed a lively interest to them. They suffered also a certain unaccountable disdain, which persists to this day, from some members of the other women’s service.

Accommodation was often less than desirable, and living conditions differed from camp to camp. Where possible, two or three would share a room: in other cases accommodation would be dormitory-style. Bathing facilities were often inadequate and laundering done under very primitive conditions. One land girl, Jean Scott, was shocked by the conditions:

Iron cots, communal hanging space, wooden packing cases for our personal belongings, one bath for 30 girls, no laundry and two outdoor toilets. That [first] night was the most unhappy, cold, lonely and homesick that I have ever experienced. I’d packed the straw in my palliasse too tight and made the bed up with sheets, two mistakes which didn’t help my plight.

‘Comfort’ items, mats, curtains or straw for palliasses, were sometimes donated by the local CWA. Some camps held dances or concerts inviting the local people, using the money they made for the comforts and amenities they were missing.

A matron was assigned to the camps. She took on the role of housekeeper, nurse, ‘part-time mother’. And she faced the mammoth task of preparing meals for her hungry ‘family’ each day.

Community trucks or wagons picked up the women from the hostels and delivered them to the farms. Others rode bicycles, sometimes up to ten miles each way.

Reproduced courtesy Australian War Memorial

Winning over the doubters

Farmers were sceptical at first, doubting that a ‘city girl’ could handle the hard physical labour. The media did little to encourage intending recruits:

The suggestion to form an army of women to do the hard work of farms is ridiculous. Our women are wonderful, but is it fair to ask them to shear or crutch sheep, to plough the land?

But respect for the AWLA came quickly. In 1943 the Sun reported: ‘The Land Army used to beg the farmers to employ their girls. Now the farmers are the ones to beg its members to help them. One grower had written to say how pleased he was with his lady pickers and hoped he would not have to revert to male labour after the war’.

Mr Broadfoot, Senior Inspector of the Department of Agriculture, offered high praise: ‘These girls are the greatest boon… both on the land and in the packing house. They have proved so capable and popular that the farmers’ wives have taken them to their hearts.’

Naida Rose and Jennie Schouewille picking asparagus.

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Mrs. M. Wilson, Mrs. R. Doherty and Miss Laurie Fielder washing asparagus.

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Harvesting asparagus also called for early starts. When the asparagus tips pushed their way through they were cut with a chisel-like instrument, thrust beneath the soil to slice the spear at the base. Small bundles were then put into heaps for the pick-up gang, who had to finish their work before the heat could spoil the cut batch.

‘There was no glory in it …’ – Land Girl, Pamela Gosney

At its peak about 3,000 women were members of the AWLA, while thousands of other women worked unpaid on family farms. In all perhaps 60,000 women contributed to rural industries.

But after the war, the contribution of the AWLA was largely forgotten. There were no post-war benefits, schemes or honours available to the land girls, and they did not march in Anzac Day parades until 1985.

Some recognition was given when, in 1995, AWLA members became eligible for the Civilian Service Medal, recognising the service of eligible civilians in Australia during World War II. And in 2012 women from the AWLA were invited to attend a dinner at Parliament House in Canberra. In her speech, Prime Minister Julia Gilliard paid tribute to their service:

You went to take up the work of the men who had let for the front. Some of them were your fathers, brothers, or even sons. In doing so, you brought victory closer, just as if you had picked up a rifle yourself.

Now, I know a thing or two about working in a traditionally male domain. But the life I’ve been privileged to lead is only possible because women of courage like you were there first; in the tough years, the desperate years, when the nation faced its ultimate test. You helped Australia pass that test. And today – here in the nation’s heart – we thank you. I know it’s been a long time coming, these words of thanks…

Ladies, each of you will return home with these certificates graciously signed by the Governor-General, and with booklets created by the Australian War Memorial and, above all, with a commemorative brooch to wear. I know you will wear those brooches with a great deal of pride. And I really hope, I genuinely hope they prompt younger Australians to ask you what they mean, because you’ll be able to tell them. You’ll be able to say ‘I answered the nation’s call. I stood up to be counted when Australia needed help the most.’ And a new generation will learn of the remarkable things you did and the remarkable women you are. So today, on behalf of all Australians, I thank you for your generosity and your service. The Australian Women’s Land Army has achieved a lasting place of honour in the history of our nation. May it be celebrated – truly celebrated – for many years to come.

Sources

Websites:

Books:

Adam-Smith, Patsy, Australian Women at War. The Five Mile Press Pty Ltd, Victoria, 2014.

Darian-Smith, Kate, On the Home Front. Melbourne in Wartime: 1939-1945, Second Edition, Melbourne University Press, Victoria, 2009.

McKernan, Michael, All In! Australia during the Second World War, Thomas Nelson Australia, Victoria, 1983.

Scott, Jean, Girls with Grit, Allen & Unwin Australia Pty Ltd, New South Wales, 1986.

Journals:

Saunders, Kay, Not for them battle fatigues: The Australian women's land army in the second world war, Journal of Australian Studies, published online 18 May 2009

Author: Old Treasury Building