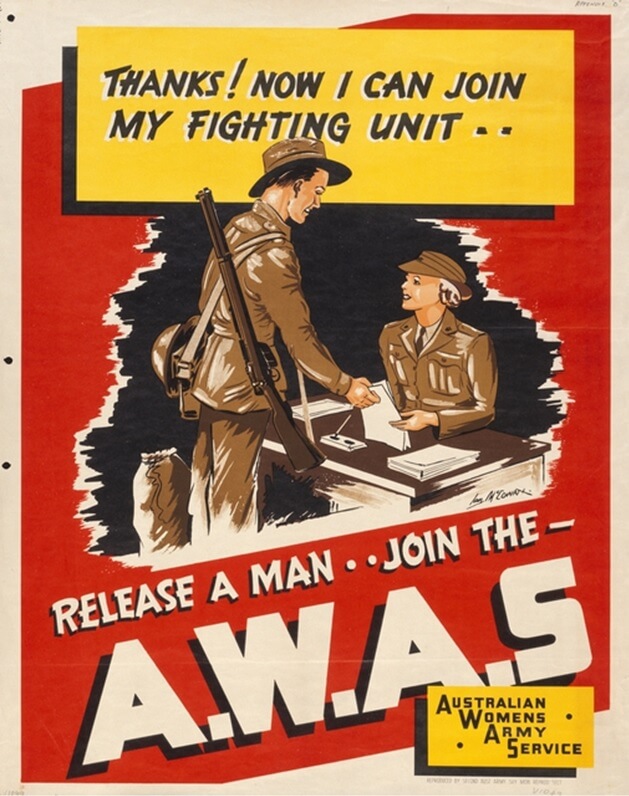

War Cabinet approved the formation of the Australian Women’s Army Service on 13 August 1941 – to ‘release men from certain military duties for employment in fighting units’.

Lieutenant Colonel Sybil Howy Irving was appointed as Controller of the AWAS in October 1941. Recruits were called up and enlistments began in January 1942, with recruit training schools established in all states.

Eligibility criteria for entry into the AWAS included:

- A satisfactory medical examination and X-ray

- Age between 18 and 40 (extended to 50 under special circumstances)

- Ability to commit to full-time military service for the duration of the war

- Security check and clearance by the Manpower Authority

- Character testimonials signed by a clergyman or municipal councillor.

Release a man … Join the A.W.A.S. by Ian McCowan, 1941–1945.

Reproduced courtesy Australian War Memorial

Early recruits were scrutinised, ‘examined under the microscope of established male army tradition’. As one AWAS officer later recalled:

When we were eventually able to get the odd seat on an army plane, we sat in rickety aircraft – no seats, sometimes on the floor, sometimes on forms lengthwise along the sides of the plane, not fastened down. When it was rough, the whole lot of us rolled off.

Then we tumbled off the plane at journey’s end and had to appear smart, yet womanly… because you must remember that, in the beginning, there had been much criticism to the effect that army life would take the lady out of women. It was very stupid, but it was the age…

It was not long, however, before the women were accepted. According to Major Jean Woods:

We just did our best… to get the service going, and once it was on its way we then did not need to do anything, because the results were so magnificent that all talk of “ladies in trousers” and the rest of it stopped.

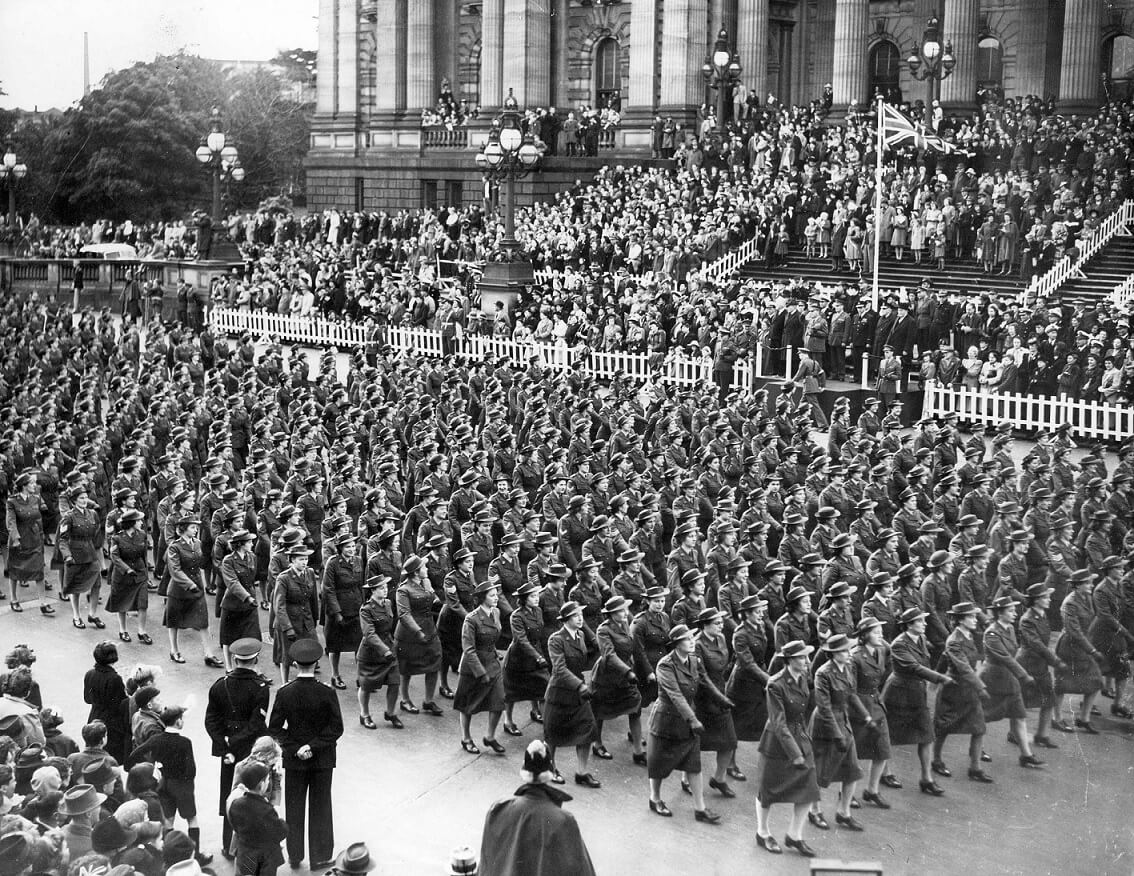

More than 24,000 women served in the AWAS and it was the only non-medical women's service to serve overseas. Approval was given by the War Cabinet in November 1944 for the posting of AWAS members to take up signals and clerical duties in New Guinea. A total of 385 AWAS members served in New Guinea, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Margaret Spencer.

Victory Day march in Melbourne, 1946. AWAS pass Victoria's Parliament House in Spring Street.

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

In the beginning, it was very hard to impress men that we would be of any use at all, let alone become a valuable arm of the military body. Sybil was, of course, impressive. She could be abrupt, decisive and self-assured in the public arena in a way women were not expected – or trained – to be in those days, and this stood her in good stead. She went from state to state selecting her officers… travelling hard all the time, but always cool and assured.

She was held in high regard in Victoria Barracks… When the pressure was intense she would relax for half an hour, striding over the Botanic Gardens at lunchtime, with me, a foot shorter than her, hitching the side of my skirt up trying to stay in step with her.

Major Jean Woods, AWAS

Colonel Sybil Irving

An AWAS girl is a soldier, doing her best for her country, just as the men are. She frees up a man to go and fight by taking on the job he’d be doing at home. That might be driving ambulances, learning signalling, cooking, typing, working in intelligence, and any number of other things that need doing on the home front. You can contribute to this war just as much as the men can. And yet. You’re not the same as the men. You will be in the Australian Women’s Army Service. You will be as feminine, as ladylike, as ever – we don’t want to take that away from you, for if we did, what are the men over there fighting for? But this is our chance to show them that feminine and ladylike can make a difference too, and that even the women can help us win this war.

Colonel Sybil Irving, Controller, AWAS

Colonel Sybil H Irving, Controller, AWAS, painted by war artist Nora Heysen, 1943.

Reproduced courtesy Australian War Memorial

Sybil Irving was born at Victoria Barracks, Melbourne, on 25 February 1897. Her father was an Army officer and Sybil moved house frequently as a child. She later recalled: 'We got used to all the travelling after a while… we had the most travelled canary I have ever known—and each trip we lost another piece of the dinner set'.

In 1924 Sybil became Secretary of the Girl Guides Association of Victoria – a position she held until 1940. In 1935, she helped to set up the Victorian Society for Crippled Children. She was a founding member of its council of management and volunteered for the institution all her life.

In 1941 she was invited to establish and administer the Australian Women's Army Service. She assumed Controller of the A.W.A.S. on 6 October 1941, and travelled around Australia by train to recruit officers. By 1944 she had more than 20,000 women under her direction.

Lieutenant Colonel Irving was an imposing woman, despite her small stature. Her father had been a Major-General and her brother was a Brigadier, and she exemplified the ideal senior officer recruit. At the time of her appointment, Sybil was forty-four and unmarried, and devoted to public service.

Under her management, the roles for AWAS women grew from typists, cooks and clerks to include the manning of anti-aircraft and coastal artillery gun sites, working in ordnance, cipher, electrical, mechanical and intelligence units, and as transport drivers. On the anti-aircraft gun sites, AWAS did everything but load and fire the guns. Women served all over the country and, from May 1945, a small number served in New Guinea.

Sybil strongly supported official policy that women in the A.W.A.S. should not bear arms. 'These girls will be the mothers of the children who will rebuild Australia', she argued. 'They must not have the death of another mother's son on their hands.' Femininity was fostered. Sybil encouraged women to take a pride in their personal appearance, allowing them to wear lipstick - ‘It makes you look better, so naturally you feel better and therefore do a better job’. She urged the women to make their living quarters as attractive, comfortable and homely as possible. Joyce Whitworth remembered that ‘…some of the girls would make bedspreads and curtains and things like that and this was her [Irving’s] idea of women remaining feminine.’ Even anxieties about the ‘uniformed woman’ were addressed:

Sybil… was absolutely insistent that… she wouldn’t have us in caps… Sybil wanted us in hats… She thought they [caps] were masculine… She didn’t want us to look like men.

To ensure the good reputation of AWAS personnel, Irving introduced strict codes of conduct for women, both in camp and when off duty. The First Officers were told:

…do let us remember always that this is the Australian Women’s Army Service. If our conduct is based on good taste and good sense it will naturally follow that conduct will be unobtrusive, courteous and natural…Another thing to watch will be our general attitude towards the men with whom we are working. To some it may be a new experience and they will need to remember that they are on a job of work and conduct themselves accordingly. Don’t be hearty – be womanly.

Sybil Irving remained in charge of the AWAS until after the war, resigning on 31 December 1946. From 1947 to 1959 she was General Secretary of the Victorian Division of the Red Cross and in 1951 was given the rank of honorary colonel in the Women's Royal Australian Army Corps, successor to the Australian Women's Army Corps. She resigned from the Army in 1961 and worked as a consultant to the Victorian Old Peoples' Welfare Organisation, retiring in 1971.

After a ‘lifetime of duty, commitment, uniforms and uniformity’, Colonel Irving died on 28 March 1973 at her South Yarra home. She was buried with Anglican rites and military honours in Fawkner cemetery.

The auxiliary services allowed members of volunteer organisations such as the Women’s Transport Corps and Women’s Emergency Signalling Corps to test their new skills.

Women served with eagerness and competence, surprising their higher-ranking male colleagues and challenging gendered assumptions.

AWAS servicewomen march through Melbourne, September 1942.

Reproduced courtesy Australian War Memorial

Many searchlight stations were manned entirely by AWAS personnel, doing their guard in all weathers.

Sgt. Jack Shaw provides maintenance instruction to AWAS members Private Irene Jack, Ida Skinner, Thelma Skinner and Violet Powell.

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Members of an AWAS searchlight crew overhaul their equipment while another member continues to search for planes, Melbourne, January 1943.

Reproduced courtesy Australian War Memorial

AWAS members handling a beach searchlight.

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Members of the AWAS took on roles such as drivers, provosts, canteen workers, cooks, typists, signallers, and cipher clerks. There were other unusual roles, such as a Japanese translator, a veterinary surgeon, and an anthropologist who liaised with Indigenous groups.

AWAS Drivers, D. Austin and D. Pelling, Melbourne, c.1944.

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria