The home was the primary workplace for most women until the 1970s. Wives and mothers were expected to remain at home, either performing household tasks themselves, or supervising others. Only a small number of professional women, or the poor, went out to work after marriage. By the middle years of the nineteenth century a new term had emerged to describe this uniquely-female occupation – the ‘housewife’. The Argus newspaper used the term in July 1868, possibly for the first time, but it was soon commonplace.

Women in the paid workforce earned far less than men, even where they did similar work. This was partly a social construct to keep women in the home. It was widely believed in the nineteenth century that women’s role as wife and mother was essential to maintaining social order, especially in new societies like Victoria. Women believed this as well as men. Caroline Chisolm, who worked tirelessly herself to bring immigrant girls to Australia and to find them suitable work, believed passionately in the civilising power of ‘wives and little children’. She also believed that women’s wages should be kept low to encourage women to marry. As she wrote in 1845:

The rate payable for female labour should be proportional on a lower scale than that paid to men… High wages tempt many girls to keep single while it encourages indolent and lazy men to depend more and more upon their wives’ industry … thus partly reversing the design of nature.

Progress

In the Factory

In the Office

-In the Home

On the Water

In Print

On the Land

On the Street

On the Tracks

On the Road

In the Shadows

Odd Jobs

Domestic service was the most common female occupation in the paid workforce for all of the nineteenth century. About half of all working women still earned their living in this way in 1901, but times were changing rapidly. More and more women preferred other work, and by 1945 the days of the live-in servant had gone for good. The burden of housework then fell squarely on the housewife.

In contrast with other areas of work, technological change was slow to reach the home. In fact, housework changed very little from the 1840s to the 1940s: it was hard, heavy work with endless repetition. Not surprisingly, many who advertised for domestic servants often specified ‘good, strong girls’. But the pace of change increased after the Second World War, as new labour-saving devices became more affordable. This was just in time, as women increasingly looked to find paid work outside the home. In 1954 one in eight married women worked outside the home: by 1970 it was one in three. Now most women are in the paid workforce, but they still perform far more household tasks than men. Some things have been even slower to change!

This section looks at the home as workplace, for both paid and unpaid workers. It is a story of slow transformation over time, with more continuities than we might imagine.

Housework

It is hard to imagine life without modern household appliances - the automatic washing machines, microwave ovens and electric kettles we use every day. Thinking about life without electricity is even more difficult. Almost everything we do now involves reliable access to power, as we discover to our cost during occasional power outages. But women in the past had none of these things. The slow transition to the modern home was just that – slow! For much of the period from 1835 to the present, women supplied the labour that cooked the meals, cleaned the houses, made, washed, ironed and mended the clothes. Most of them were unpaid wives, mothers and daughters.

Wives and mothers

Watching period dramas suggests that households in the past were full of servants, but the reality for most people was very different. For all of this period, most household work was performed by wives, mothers and daughters. Although domestic service was a very common female occupation, there were never enough servants to meet the demand for them, and most women had to do at least some of their own housework. It is also important to understand that even with Victoria’s relatively high wages, most families could not afford even a general servant, let alone the range of maids employed in wealthy households.

Most families in the past also included far more children than the average family today, and there is good evidence to suggest that families were even larger in Australia than in Britain at the same time. This was probably because women tended to marry earlier in Australia. While family size varied a great deal from one household to another, it was not unusual for a woman who married in the 1850s to have seven or more children over her lifetime, while many had more than this. There was no reliable means of contraception available until quite late in the nineteenth century (and arguably much later than this,) and no real understanding of how female reproduction worked until about the same time. That meant that a woman might expect to have her first child quite soon after marriage, with another baby following every two to three years until she reached menopause. The only sure way to avoid conception was to abstain, and not surprisingly this was never a very popular option! All of which meant that before about the 1920s children tended to grow up surrounded by a sizeable group of siblings, all of whom had to be fed, clothed, and housed. Contrary to popular opinion, infant mortality, although much higher than today, was not as high in Australia as in Britain or Europe. While families might well experience the death of one or perhaps two children, it was unusual to lose more than this. Large groups of siblings were the norm until about the 1920s.

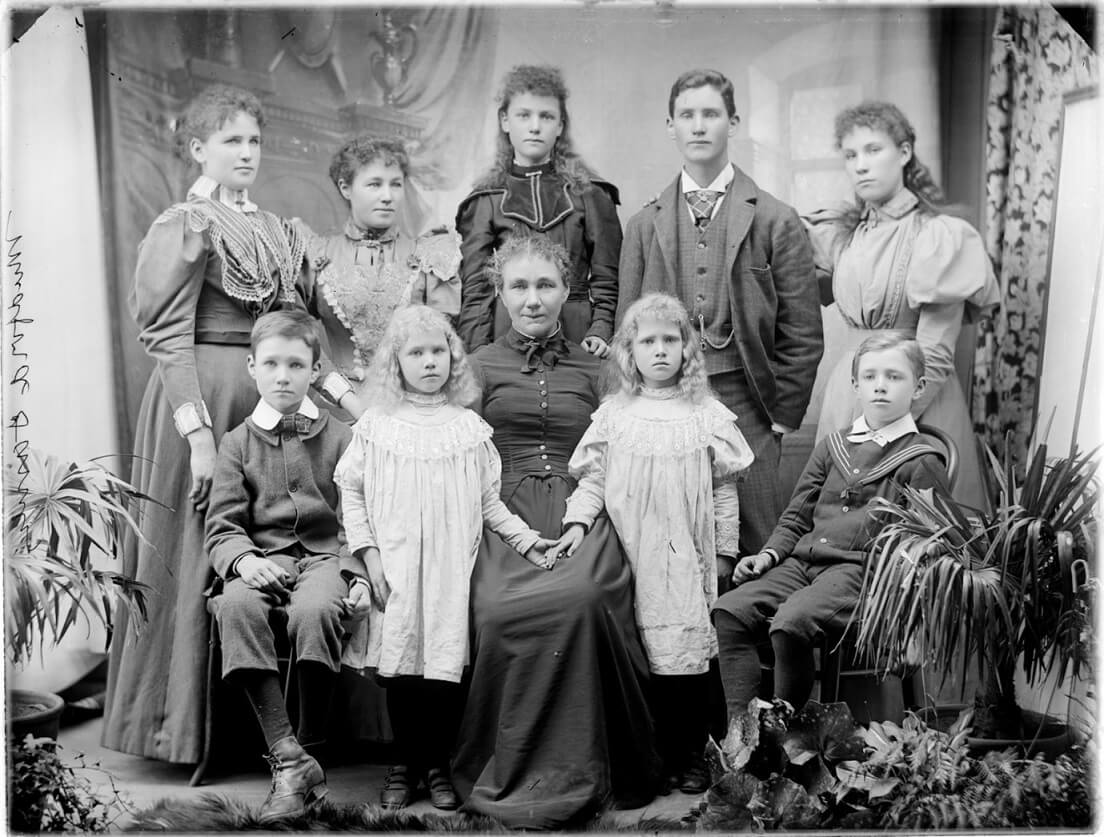

The Mudford family, Kyneton, 1890s

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Families of this size were quite common in the 1890s, although family size was definitely falling. Mrs Mudford was pictured with nine children, including twin girls. Caring for a family of this size involved a great deal of work and girls were usually expected to help in the house. Boys often had jobs outside.

Then as now, babies and children made for a lot of work and mothers with large families, who found time to write at all, often recorded their exhaustion at the end of each day. Let’s look at some common household tasks and think about how they were done in the past.

Author: Margaret Anderson

Next Topic- On the Water

Further Reading:

Anderson, Margaret, ‘Good Strong Girls: colonial women and work’, in Kay Saunders & Raymond Evans (eds) Gender Relations in Australia: Domination and Negotiation. Sydney, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1992, pp. 225-45.

Australian Bureau of Statistics ‘Trends in Household Work’, Australian Social Trends, March 2009: https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/lookup/4102.0main+features40march%202009

Aveling, Marian & Damousi, Joy (eds) Stepping Out of History: documents of women and work in Australia. North Sydney, Allen & Unwin, 1991, especially chapters 2, 3, & 5

Bosworth, Michal Australian Lives: a history of clothing, food and domestic technology. Melbourne, Nelson, 1988

Clarke, Patricia Great Expectations: emigrant governesses in colonial Australia. Canberra, National Library of Australia Publishing, 2020

Cramer, Lorinda Needlework and Women’s Identity in Colonial Australia. London, Bloomsbury, 2021

Darian-Smith, Kate, On the Home Front. Melbourne in wartime: 1939-194. Second edition, Melbourne University Press, 2009.

Evans, Raymond & Saunders, Kay, ‘No Place Like Home: the evolution of the Australian housewife’, in Evans & Saunders, Gender Relations in Australia, pp. 175-91

Friedan, Betty The Feminine Mystique. New York, Norton, 1963

Howard, Sally, ‘Coming Clean About Housework’, Australian Financial Review, 20 June 2020: https://www.afr.com/work-and-careers/workplace/coming-clean-about-housework-20200601-p54yik

Kingston, Beverley Basket, Bag and Trolley: a history of Shopping in Australia Melbourne, Oxford University Press, 1994

Kingston, Beverley My Wife, My Daughter and Poor Mary Ann: women and work in Australia. Melbourne, Thomas Nelson, 1975

Russell, Penny A Wish of Distinction: colonial gentility and femininity Carlton, Melbourne University Press, 1994

Strasser, Susan Never Done: a history of American housework. New York, Pantheon, 1982. New edition published 2013

Webber, Kimberley Romancing the Machine: the enchantment of domestic technology in the Australian home, 1850-1914. PhD thesis, University of Sydney, Department of History, March 1996