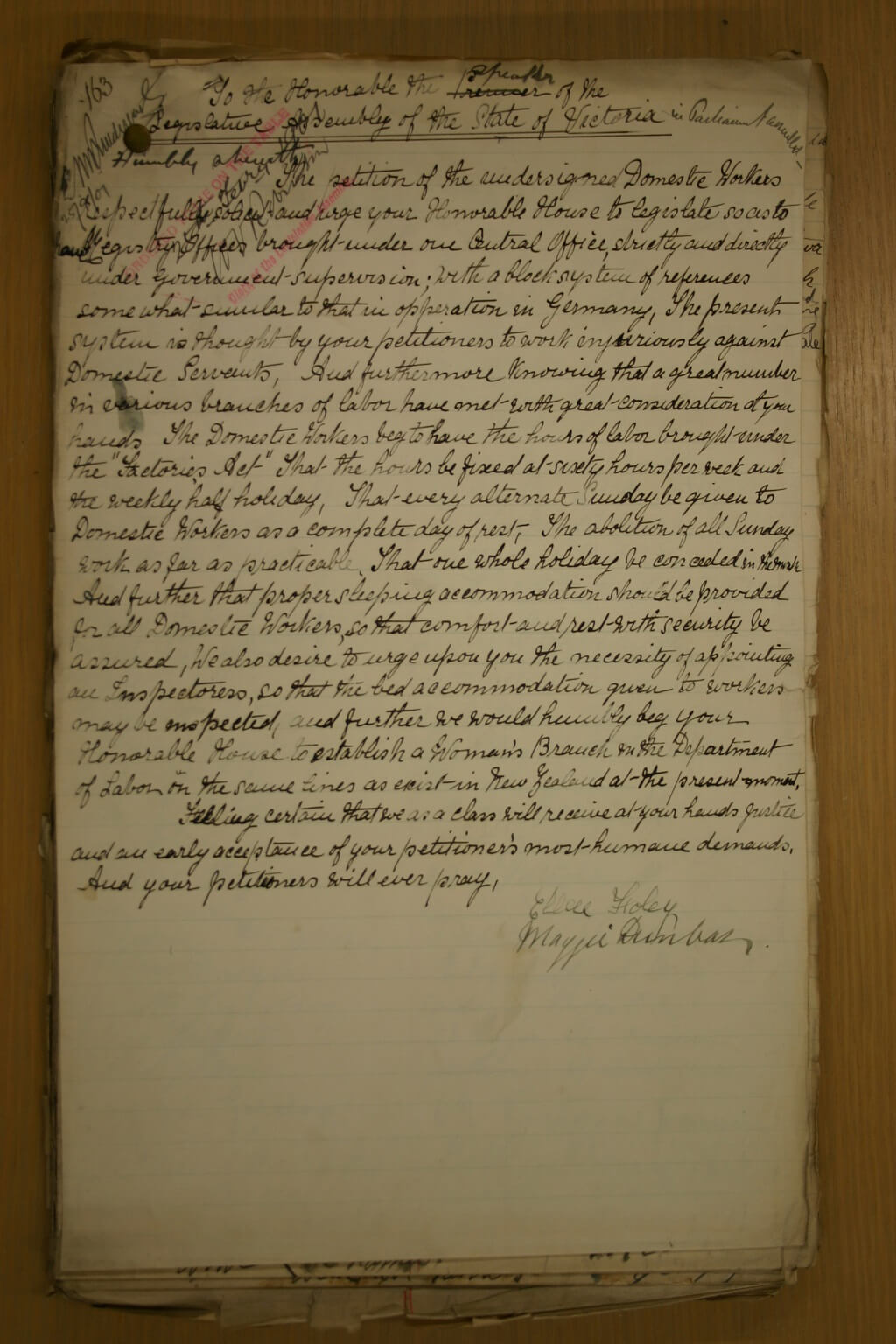

Housework was hard, dirty work. Not surprisingly, those who could afford it employed others to do it for them. In the highly-gendered employment market of the nineteenth century, women were excluded from most jobs and often had little choice but to find work as servants. Domestic service was poorly paid, even in Australia where wages for men were often higher than in Britain. It also frequently required women to live in, where they could be on call at all hours. A servant’s day often began before six in the morning (or five am on wash days) and did not end until well after six or seven at night. A common arrangement allowed every other Sunday off, but some servants were also allowed an hour or two of rest during the afternoon. It all depended on the mistress. One article in a popular series published in the Herald, and purportedly written by ‘An Old Housekeeper’, suggested that a fair wage in 1882 was ten or 12 shillings per week, with ‘plain food’. For this she suggested that ‘poor Mary Ann’ should be expected to work no more than 10 hours per weekday, (by which she meant Monday to Saturday,) and no more than five or six hours on a Sunday. As she pointed out, even these reduced hours asked more of poor Mary Ann than was required of most men at the time. (Herald, 22 December 1882) However even this suggestion was controversial, as An Old Housekeeper admitted. Several correspondents wrote to the Herald complaining that her suggestions were ridiculous and would cause great inconvenience to the household. The implication was that many servants were expected to work more than 12 hours per day. That such hours were common into the early twentieth century is suggested by a remarkable petition from domestic servants working in Melbourne in 1901. In their petition the workers asked for a maximum working week of 60 hours, with every other Sunday off, suggesting that the regular day off was less common than was often assumed. The petitioners also asked for ‘proper sleeping accommodation’ and for this to be inspected, implying that households often misled their servants about the arrangements on offer. There were many reports of servants being required to sleep on kitchen floors, or on verandahs, with little privacy. There is no record of any legislative response to the petition.

Petition from domestic workers seeking a legal limit to working hours and better conditions, 1901

Courtesy Public Record Office Victoria, VPRS 3253/P0, unit 906

The servant ‘problem’

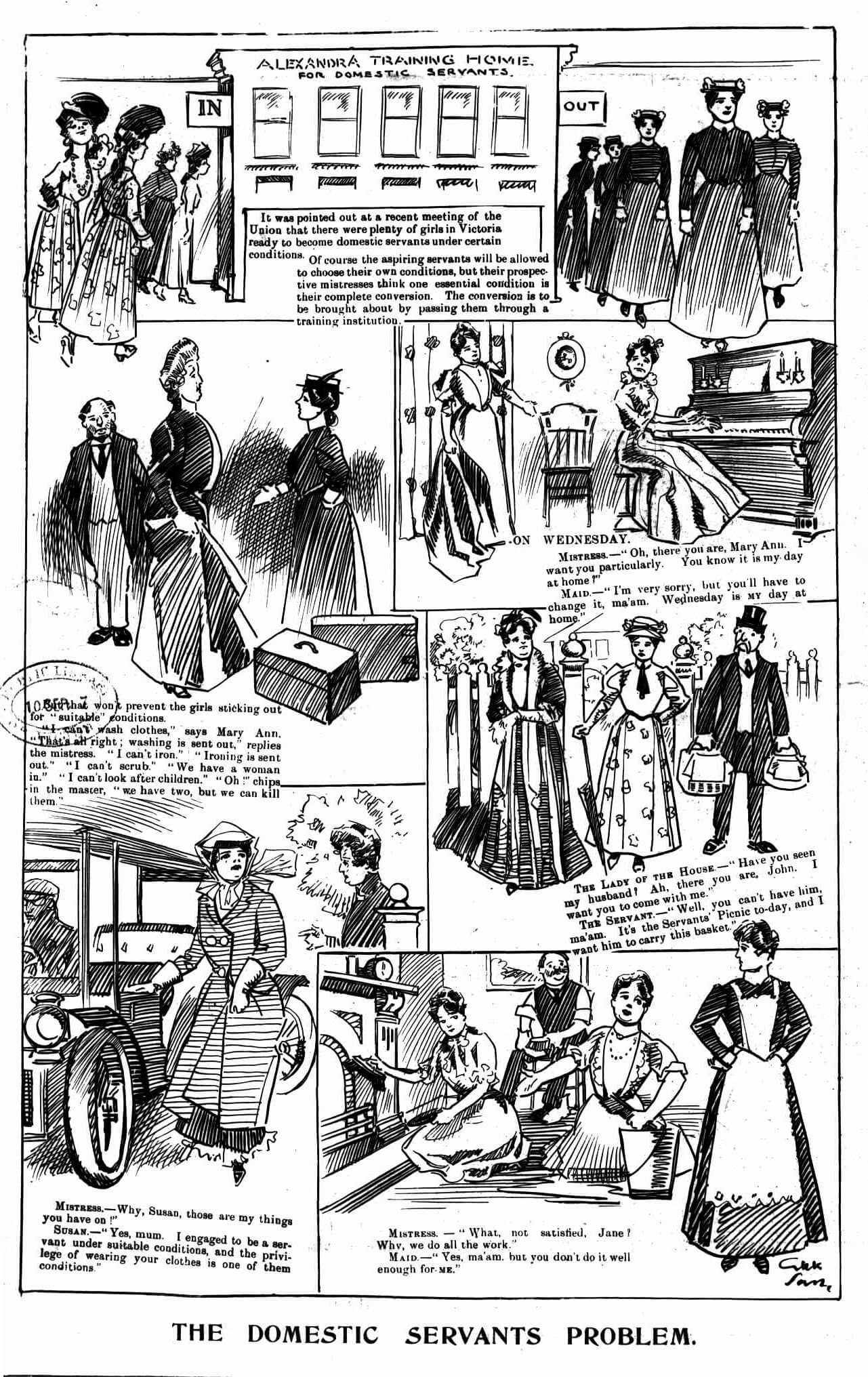

The articles by An Old Housekeeper were unusual: far more common were complaints from mistresses about their servants. The main grievance was always the shortage of servants, but employers also complained endlessly about their unreliability, their general incompetence and a lamentable absence of proper deference, this aimed in particular at the colonial ‘gal’, who was thought to be far more independent than her English equivalent. In the early years at Port Phillip employers sometimes resorted to importing indentured servants from Britain at lower wages, but inevitably the servants swiftly realised their disadvantage and many simply absconded. Attempts to enforce such arrangements through the punitive Masters and Servants Acts was rarely successful. Resentful servants exacted their own revenge. In following decades a common theme of the emerging art of satirical cartooning was the topsy-turvy world of the colonial household, in which the servant held her hapless mistress to ransom with her unreasonable demands.

‘The Domestic Servants Problem’, Melbourne Punch, 5 September 1907

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

From the general servant to the lady’s companion

Domestic service encompassed a multitude of different jobs. By far the most common position in Victoria was that of the general servant. As the term implies, the general servant was expected to do pretty well everything and was often the only servant in a household. An Old Housekeeper’s remarks were addressed to the mistress of such a servant, who usually worked in a household that might have been described as respectable but not wealthy. Wealthy households might employ many servants, including any of a range of more specialised servants. There were kitchen maids (who assisted the cook), scullery maids (who did the washing up and heavy cleaning), parlour maids (who served food and performed a range of cleaning tasks), nursery maids (who looked after the work associated with the nursery), and personal maids (who dressed the mistress and other women in the household and cared for their clothing). In a very wealthy household there might be a butler (always a man), a valet for the master (also a man) and a housekeeper (a woman). Where there were children there could be a nurse (assisted by a nursery maid), and/or a governess (for school-age children). A mother who was unable to breastfeed her child might also employ a wetnurse, who either moved into the household for a year or so, or took the infant into her home. Wetnurses were usually poor women whose own infants had died. Sometimes they were unmarried women who placed their infants elsewhere. [could ref to Maggie Heffernan?] Another common occupation was that of ‘lady’s companion’, a kind of in-between servant who kept a woman company, performed little tasks for her (like sewing or mending), chaperoned her if she was unmarried and generally made herself useful, but did not perform cleaning or other more arduous household tasks. Nor did she dress like a servant, in the starched apron and cap that seems to have been common for servants in wealthy households.

Photograph labelled ‘Belle Richmond 1900’, by Dudley Le Souef, photographer

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

This is a rare photograph of a named domestic servant, shown carrying a tea tray in a garden. Her long, white pinafore and cap seems to have been a common uniform for servants in wealthy households, or in hotels, boarding or coffee houses. This particular apron is richly decorated with lace insertions on the bib.

Men also worked as servants, although in far smaller numbers. Many jobs for men were associated with the outdoors, from gardeners to the more general ‘outdoorsmen’. Households that kept a carriage and horses might employ a driver and/or a groom and a stable ‘boy’. Then a range of other workers might be employed for specific tasks, often by the day. They included seamstresses or dressmakers, washerwomen, chimney sweeps, window cleaners and carpet cleaners/beaters.

Children

Children often began work as domestic servants at quite a young age, although the age of employment increased as the nineteenth century progressed. Early in the century girls as young as ten or eleven might find work as ‘mothers’ helps’, nursery maids or scullery maids, progressing to general servants or more specialised work as they learned more skills. Boys often began as stable boys or gardeners’ assistants. With the advent of compulsory schooling children generally began work later, but many expected to be in the workforce from the time they turned 14 or 15. From 1875 children were required to attend school between the ages of seven and thirteen, but this was easily evaded at the beginning.

The perils of service

Life as a domestic servant held many perils. One that loomed large was the risk of sexual molestation by the master, older sons of the household, or other servants. This was a particular problem where female servants were not allotted bedrooms with doors that locked. Nineteenth-century mistresses were acutely aware of this problem, as were those assigning servants. Caroline Chisholm enquired carefully about the moral standing of families before sending young women to them, and travelled many miles in regional Victoria escorting such women to their new homes. She also noted the reluctance of some potential mistresses to take especially-attractive young women into their homes as servants.

However unwanted pregnancies were common amongst domestic servants: both Sarah Lawton and Gertie Bigwood bore illegitimate children within a year of their release from the industrial schools, and such women were frequent inmates of the various homes for unwed mothers. The fate of such women was very unjust: many were promptly dismissed, often without a ‘character’ (reference), leaving them facing immediate destitution. Their sexual partners, or seducers, almost never were either named or held accountable. Faced with this predicament, and the associated disgrace, some women sought out one of the many abortionists who worked in the shadows of Melbourne’s society. Others gave birth to their babies and surrendered them for adoption. In some tragic cases the babies were either abandoned, sent to the ‘care’ of a ‘baby farmer,’ or even killed by their mothers in desperation. It was almost impossible for a woman to support herself while caring for an infant or small child, as most jobs in service required the woman to live in.

The demise of domestic service

Not surprisingly, women were less and less inclined to enter domestic service when alternative employment was available. Increasingly, Victorian working women found more congenial work in the expanding manufacturing sector. Although the pay was not necessarily better and the hours were often long, they did not have the constant supervision of a mistress to contend with, while their Sundays were their own. In 1857 two-thirds of working women were employed as domestic servants. By 1901 this had declined to 50 per cent and by 1945 to just 18 per cent. By then the day of the live-in servant was well and truly past for all but the wealthiest Victorian households.