The right to protest is important in a democracy. Many democratic nations include that right in their constitutions, or in separate legislation like a bill of rights. This is not the case in the constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia, although two states have taken that step separately – the ACT and Victoria. In Victoria the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act (2006) established the right of Victorians to freedom of expression, peaceful assembly and freedom of association- all important components of the right to protest.

A long history of protest

But long before 2006 Victorians exercised what they saw as their right to protest. Indeed public protest dates back to the earliest decades of Melbourne’s history. Well before most residents of Melbourne had the right to vote, they took to the streets to express their views. The first recorded protests took place in the 1840s as Melburnians expressed their disapproval of rumours that the British Government intended to send convicts to Port Phillip. This turned out to be far more than a rumour, as a ship carrying convicts berthed in Hobsons Bay in 1849. So great was the feeling against convicts that Lieutenant-Governor Charles La Trobe paid the captain of the vessel £500, a very large sum at that time, to sail on to Sydney. Protest in Melbourne had claimed its first victory!

Separation

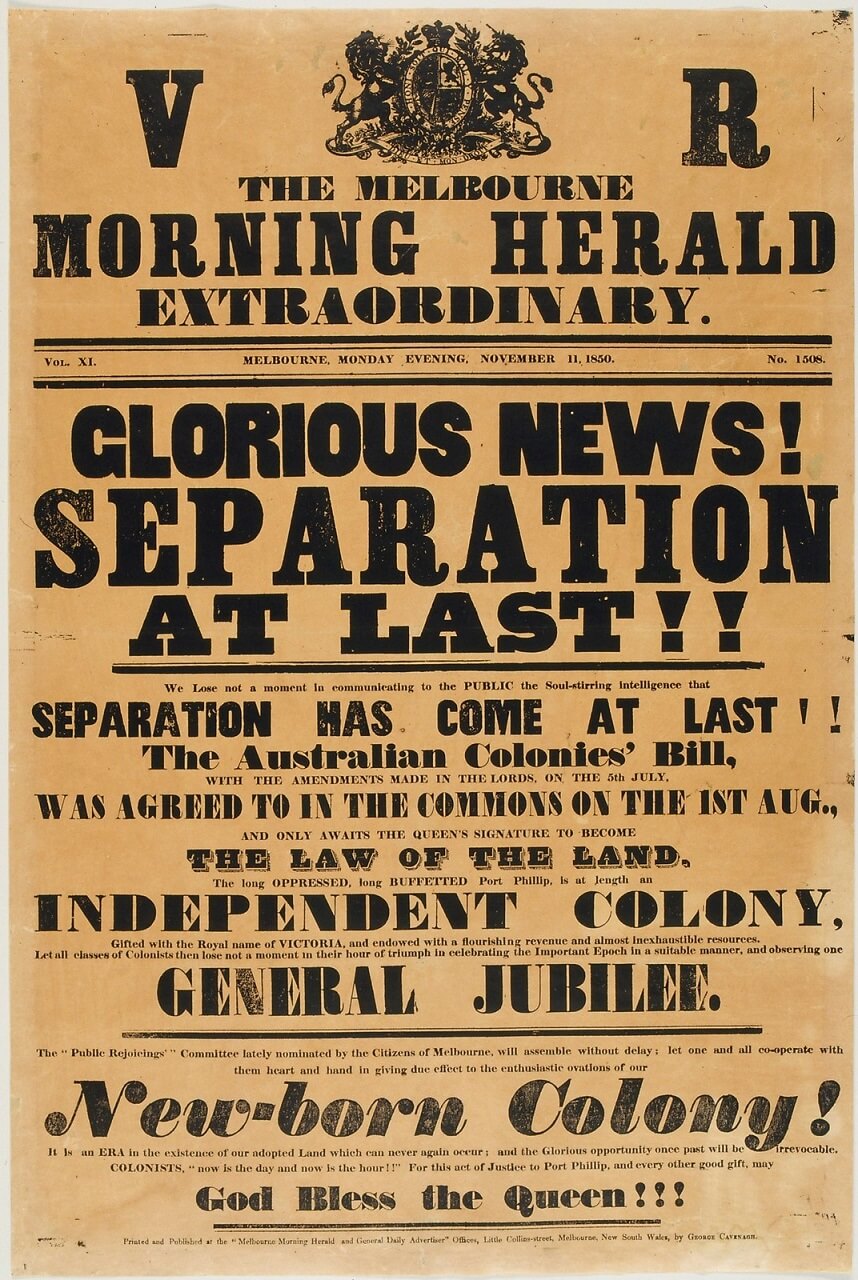

Another issue that stirred public opinion at the same time was a strong desire for the Colony of Port Phillip to be governed from Melbourne rather than Sydney. Until the two colonies separated formally on 1 July 1851, Port Phillip was part of New South Wales and all major decisions were made in Sydney. What was worse, a large proportion of the profits made from booming land sales in Melbourne were spent in Sydney – to the great annoyance of Melbourne’s businessmen.

The first protest meeting calling for separation from NSW was held as early as May 1840, when the town was less than five years old, and meetings continued throughout the next decade. A Separation Association was formed and in December 1840 this organization drew up what was almost certainly Victoria’s first petition, which was sent to Queen Victoria. It fell on deaf ears. The British Government had no wish for a separate colony at Port Phillip and instead offered to reform the NSW Legislative Council to allow for a majority of elected representatives, including six to represent Port Phillip (although only one for Melbourne). The franchise was limited to men of property – those who owned either property worth £200 or who paid an annual rental of £20. From the very beginning, Melbourne was substantially under-represented.

The other problem was finding men who were prepared to stand for election, since the (unpaid) representatives were expected to spend significant amounts of time in Sydney. Not surprisingly only three local men could be found to stand at the first election in 1843, the other three being residents of Sydney who also owned property in Melbourne.

Riots in the streets

When the first elections were held in June 1843 feelings ran high. In Melbourne electors divided on bitter sectarian lines. The leader of the separation movement, Edward Curr, was the obvious candidate to represent Melbourne, but he was a Roman Catholic. It was not long before Melbourne’s Protestants found an alternative candidate, Henry Condell, to stand in opposition to Curr. On election day vocal opponents gathered at the polling place, hoping to influence electors. Since voting took place in public at this time, electors were often jostled, cheered, or booed as they cast their votes. On this occasion the Protestants had the numbers and Henry Condell was declared the victor, to the bitter disappointment of Melbourne’s Catholics. As the result was declared, fighting broke out in the streets, and in the end authorities were forced to read the Riot Act to restore order. It was not a promising start to parliamentary elections in Victoria!

‘Glorious News! Separation At Last!’ poster issued with the Melbourne Morning Herald, 11 November 1850

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Turbulent times

In the lead up to Separation there was much animated debate in Victoria about the merits of a more democratic form of government, but in the end, the constitution agreed for the new colony of Victoria left a controlling influence with the Lieutenant Governor and his executive. There were many at the time who were deeply suspicious of democracy, which they saw as rule by ‘the mob’. Men of property believed that they were the most appropriate people to govern and this was reflected in the franchise for the new Victorian Legislative Council: only men who held property to the equivalent value of £10 in annual rental, or who held a pastoral lease, were entitled to vote. Representation was heavily weighted towards rural areas. But the times were changing rapidly. Democratic ideas were spreading throughout Australia, Britain, America and parts of Europe at this time, and soon many of the men and women involved in those movements elsewhere would arrive on Victoria’s shores.

Revolution!

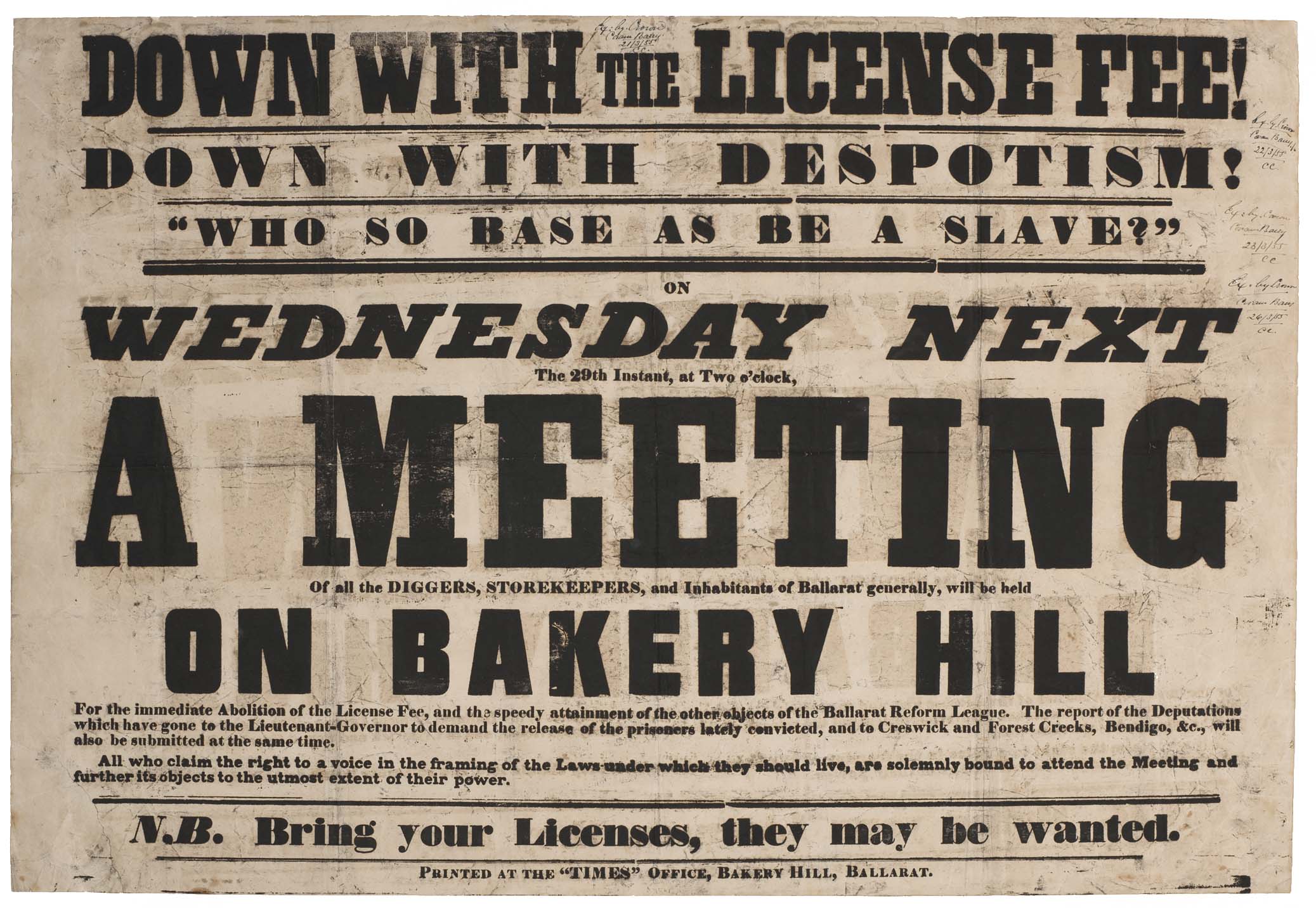

At various times in Victoria’s history public unrest was sufficiently widespread to pose a real threat to government. The first occasion was during the gold rushes of the early 1850s, when miners, angry at what they saw as excessive gold license fees, united to demand an end to ‘tyranny’. Several ‘monster’ meetings were held on the gold fields, and speakers repeated the rallying cry of the American Revolution 80 years before – ‘No taxation without representation.’ Other resolutions called for many of the reforms we now associate with democratic government – manhood suffrage (although not yet universal suffrage), voting by ballot, payment of MPs and regular elections. Amongst the miners were many chartists, members of a political reform movement active in Britain in the 1830s and forties. There were also miners who had fled persecution after failed democratic revolutions in several European countries in 1848. When a group of miners in Ballarat armed themselves and built a defensive stockade in December 1854, many in government regarded their actions as treasonous rebellion. Wealthy citizens in Melbourne feared a ‘democratic revolution,’ but many, perhaps most Melburnians, supported the miners.

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria, VPRS 5527/P0, unit 4, item 1

Original meeting placard rallying ‘the inhabitants of Ballarat’ to Bakery Hill on 29 November 1854. Reports suggest that 10,000 people, about one third of Ballarat’s population, attended the meeting.

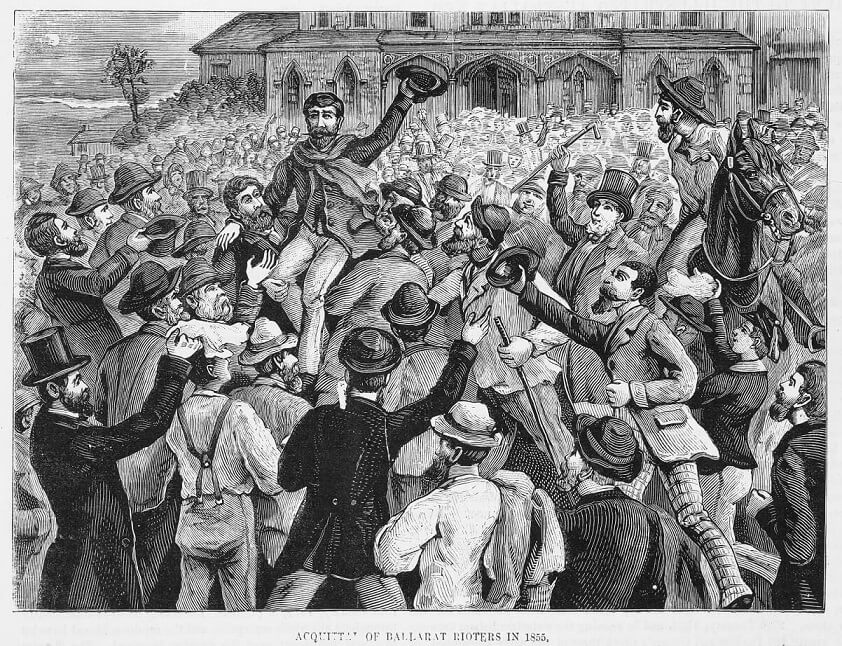

The ‘Eureka Rebellion’

Of course the battle at the Eureka Stockade was brief and resulted in the complete defeat of the miners. Several were arrested and charged with treason. But when they came to be tried angry mobs stationed themselves outside the Supreme Court in Melbourne, demanding their release. Perhaps not surprisingly the beleaguered juries refused to convict and there was wild rejoicing in the streets as each man was acquitted. Reform of the license system and important political reforms followed shortly afterwards. In what may seem a rather amusing side issue, when a new building was constructed for the Parliament of Victoria in the late 1850s-early 1860s, narrow rifle slits were built into the parapets, to allow police or soldiers to fire on any mob threatening Parliament. The slits were never used, but they can still be seen from the street, and are a reminder of the turbulent years of the 1850s.

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

The freed men paraded through the streets of Melbourne, cheered by thousands of people.

Anarchists, Bolsheviks and ‘Reds under the beds’.

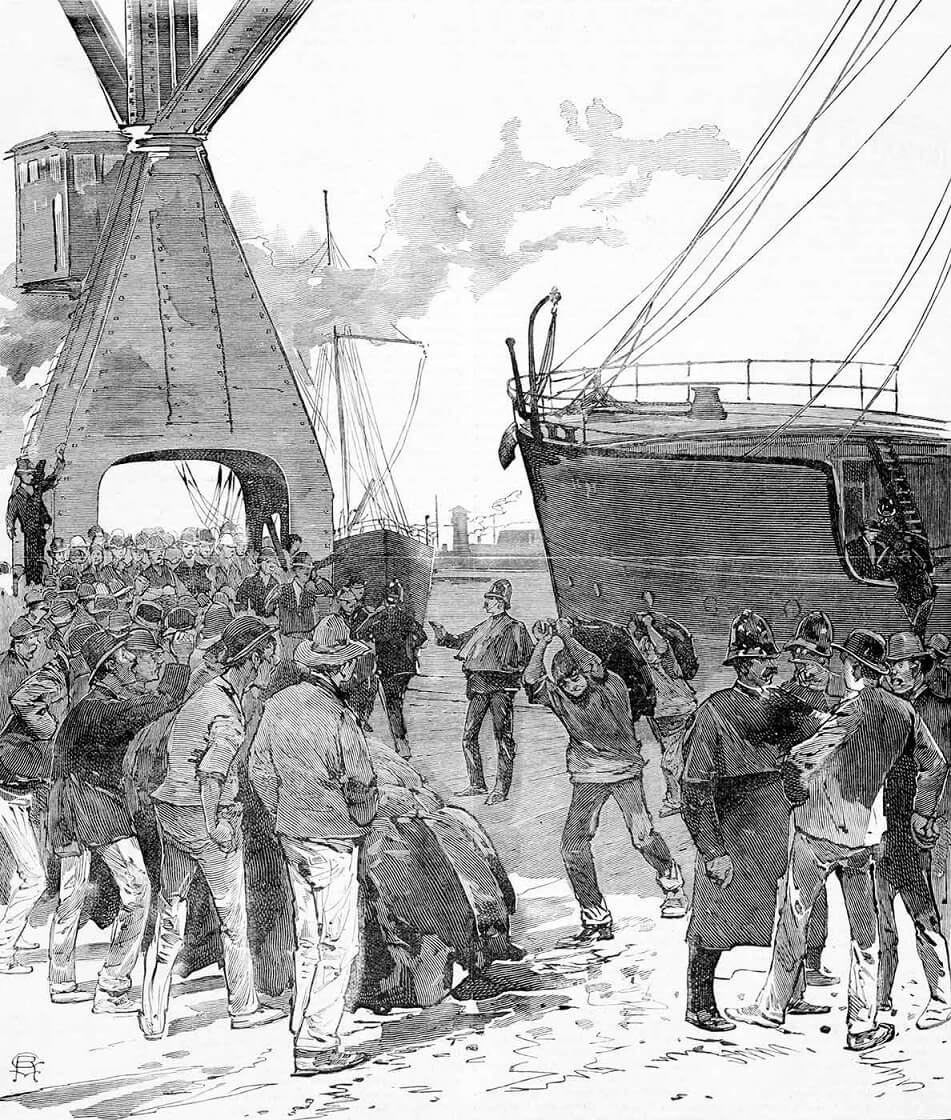

1890s strikes

There were other occasions in later decades when government seriously worried that citizen protest would turn into anarchy. During the 1890s widespread worker dissatisfaction fueled a series of huge strikes, as shearers, maritime workers, then miners and gas workers struck over pay and conditions. Feelings ran high in Melbourne as industry ground to a halt and angry employers tried to recruit replacement (‘scab’) workers. Unfortunately for the strikers Victoria was soon in the grip of a deep depression and the strikes came to nothing, but not before there were wild confrontations on the wharves as angry unionists set upon scab workers.

‘Wharf labourers working under police protection during the 1890s strike, Vic.

John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland; Negative number: 12096

World War I

The First World War was another flash point for violent protest in Melbourne. Although most Victorians supported the war and the war effort, there was increasing anger as uncontrolled inflation drove food prices higher, while wages were frozen. Protest marches erupted in Melbourne’s inner suburbs, as poor women struggled to feed their families. Melbourne’s socialist movement supported the marches and the activists Jennie Baines and Adela Pankhurst were imprisoned for their alleged leadership of the ‘food riots’ as they were called. Both were sent to Pentridge Prison.

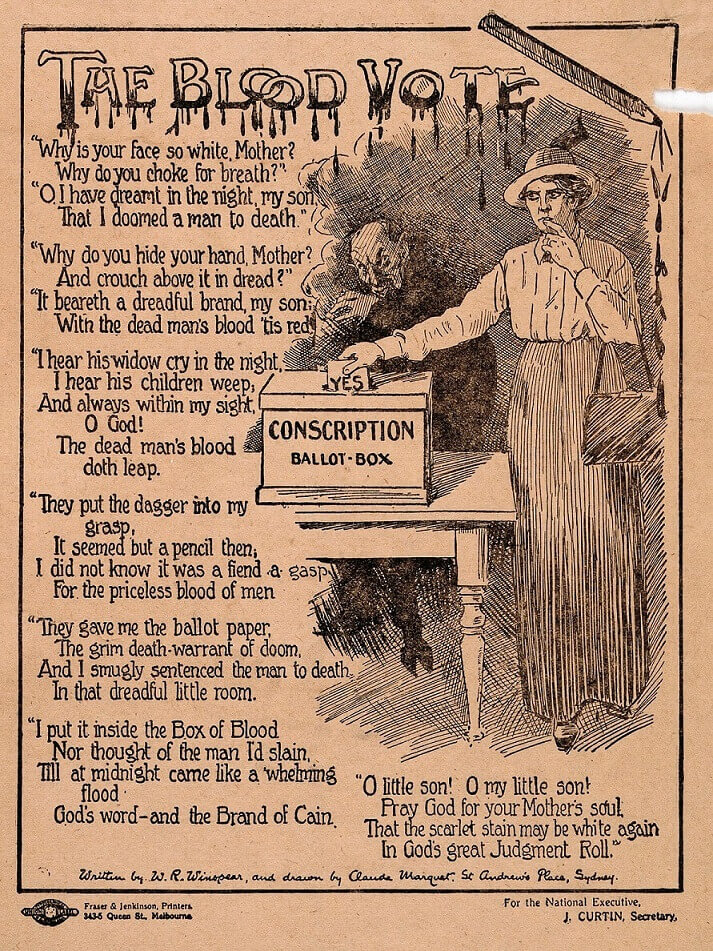

But it was the issue of conscription that really galvanized public opinion. When the Federal government proposed in 1916 to introduce conscription to compel eligible men to serve in the forces overseas, it sparked furious debate on both sides. Huge meetings rallied either for or against conscription, accompanied by a virulent propaganda war.

The Blood Vote, famous poster of the anti-conscription campaign. Drawn by Claude Marquet, words by C J Dempsey.

Reproduced courtesy Australian War Memorial

Two referendums were held, in 1916 and 1917: both were lost amid great bitterness and rancour. Government feared the influence of ‘anarchists’, and after 1917, the ‘bolsheviks’. Some feared an imminent Bolshevik revolution in Melbourne. Such was their fear that the indomitable socialist Jennie Baines was imprisoned in 1919 for the apparently-minor offence of ‘flying the red flag’ on the Yarra Banks and then refusing to promise not to fly it! She promptly went on a hunger strike in prison, almost certainly the first hunger strike in a Victorian prison.

E.J. Holloway, secretary of the No Conscription Committee during the World War I, addressing an anti-conscription rally at Yarra Bank, 1917

Reproduced courtesy Melbourne University Archives

‘Reds under the beds’

The threat of communism continued to frighten Victoria’s rulers, even during the otherwise-prosperous 1950s and sixties. Against the backdrop of the so-called ‘Cold War’, Victoria’s activists were closely monitored by Australia’s secret service agency ASIO, who kept a particular watch on supposed Communist Party members in the union movement. As opposition to the Vietnam conflict grew, and Australia faced conscription once again, mass student protest seemed to threaten the state with ‘anarchy’ once more.

Climate ‘warriors’

The end of the Cold War saw an effective end to fears of a communist takeover, but some of the rhetoric of past eras lingered. In 2019 Liberal Prime Minister Scott Morrison described environmental activists as ‘anarchists’ and threatened to legislate to outlaw their protests.

The power of the people

Protest has been a valued part of Victoria’s democratic system from the earliest days of the city. Long before most citizens were allowed to vote, they realized the power of speaking with a united voice in public. And their voices were heard on many critical occasions. The power of the people won important victories as early as the 1840s and fifties: indeed it was instrumental in creating the democratic system we value today. On each occasion, the extension of democratic rights followed determined public campaigns, first to men, then women, and finally, after a shamefully long period, to First Nations people.

In the 1960s and seventies the determination of young protestors helped to bring Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam conflict to an end: more recently the huge gatherings voicing concern at environmental issues have helped to force all major political parties to take those concerns seriously, even if the desired policy changes are yet to follow. People power is a potent force in a democracy and in Victoria it has seen regular expression, as this exhibition makes clear.