The campaign for workers’ rights - for better wages, conditions or working hours - has a long (and loud) history in Victoria.

In 1856 a group of stonemasons in Melbourne first made a stand. They demanded a shorter working day - ‘eight hours labour, eight hours recreation and eight hours rest’. Melbourne building workers were among the first in the world to gain an eight-hour day, followed by metal workers in the 1870s.

The expansion of commerce and industry in the 1870s and 1880s brought a concentrated workforce with it. Working conditions came under pressure and workers became ‘increasingly aware of the powers inherent in organisation’. Australia, the ‘workingman’s paradise’, proved a fertile ground for the fledging union movement and by the 1890s there were 200,000 union members spread across 1400 unions, ‘making Australia the most unionised nation in the world per capita’. The larger unions were those of navvies (men who built the railways), shop assistants, coalminers, railway workers and maritime and wharf labourers.

The fight for workers’ rights continues today. Issues of privatisation, de-regulation, the attempted abolition of penalty rates and the use of contract and casual labour have occasioned public protest. One of the largest rallies in Victoria’s history occurred in November 2005 when more than 150,000 people marched in protest against the Liberal Howard Government’s industrial relations legislation known as WorkChoices.

The eight-hour day

It is neither right nor just that we should cross the trackless region of immensity between us and our fatherland to be rewarded with excessive toil, a bare existence and a premature grave.

James Galloway, secretary of the Operative Stonemasons Society, 1856

On 21 April 1856 stonemasons working at the University of Melbourne walked off the job – demanding shorter working hours. After months of negotiation, their protest was rewarded and their working day was reduced from ten to eight hours, for the same wage.

[The masons] have succeed, at least in all the building trades in enforcing [the 8 hour day] without effort. The employers have found it necessary and politic to give in, and without struggle; agreeing, we believe, to pay the same amount of wages as formerly for ten hours' labour.

The Herald, 1 May 1856

The success of the stonemasons’ campaign for the Eight Hour Day was celebrated on 12 May 1856 with a grand march from Carlton Gardens to Cremorne Gardens in Richmond. Known as the Eight Hours Procession, the march on Labour Day became a major event in Melbourne. (In 1955 it was replaced by the Melbourne Moomba Festival parade.)

Workers in the parade marched under the banner of their union.

Eight Hours Procession, 17 April 1914

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

The Eight Hours Procession, 1905

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Carlton Brewery in Melbourne adopted the eight-hour day in 1885. This photograph shows the 8-hour day street parade in 1905 – and the Carlton Brewery mascot, John Jolly Barleycorn, has pride of place. The float was the height of a building and the wheels were giant barrels made at the brewery’s cooperage. The Australian Brewers’ Journal described it:

It took the form of a perambulating emblem of geniality, whose fat smiling face and inexhaustible good humour were presumably attributed to a moderate but regular indulgence in the famous Carlton brews.

Only some workers, mainly in the building trades, were awarded the eight-hour day at this time. Most workers, including women and children, had to work much longer hours for less pay and it was not until 1948 that the Commonwealth Arbitration Court approved a 40-hour, five-day working week for all workers.

But this fight for the eight-hour day was a watershed moment - the first of many campaigns for better working conditions.

United we stand

Union membership increased in the late-nineteenth century with trade and labour councils mediating disputes between workers and employers. With unions came the bargaining tool of withdrawal of labour – striking and public protest.

Melbourne has ‘a rich history of strike action’. One of the first strikes in Melbourne was in 1857, which saw a wage rise at the Argus newspaper. In 1882 Beith Shiess & Co, a clothing manufacturer, tried to reduce the wages of its women workers. The workers struck, winning their demand for better pay. They formed the Tailoresses Union - Australia’s first union comprised wholly of working women. Strikes continued throughout the 20th century. In May 1903 railway employees went on strike for nine days and in 1911, workers at the Sunshine Harvester Works laid down their tools, calling on the owner, H.V. McKay to dismiss non-union labour. McKay refused and locked unionised workers out of his factory.

The 1890 Maritime Strike was the largest and longest strike to date. Union members in Melbourne struck in August and were soon followed by coalminers, gas stokers, transport unionists and shearers in four states. By September, 50,000 workers throughout Australia and New Zealand were involved.

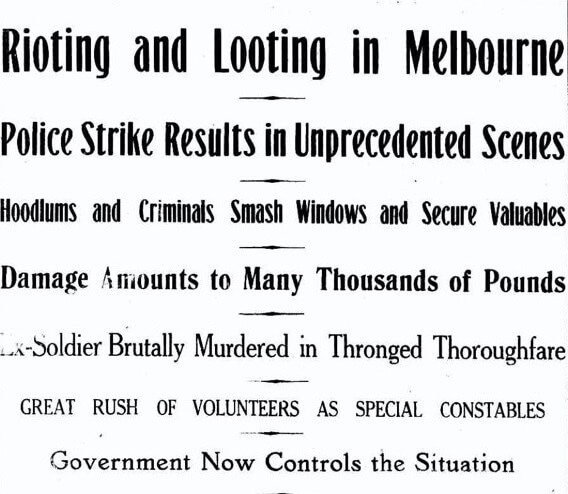

Perhaps the most memorable strike in Melbourne took place in 1923, when over 600 police struck, protesting against a ‘spook’ system in which plain-clothes officers spied on police on the beat. Without police on the streets, rioting and looting broke out, with 78 shopfronts smashed and a tram set alight. Volunteer ‘special’ constables were sworn in to restore order, but they struggled to keep the peace. Outside the Town Hall, a ‘crowd of thousands’ attacked the constables, ‘pelting them with missiles and forcing them to retreat until reinforcements arrived and the crowd was driven back by fire hoses and batons.’

The Age newspaper reported:

Emboldened by the disorganisation of the police force, the worst elements of the population ran amok, and for a while Melbourne and all it contained was theirs. Shop windows were ruthlessly smashed. Jewellery shops were looted. Clothing establishments were plundered. Those citizens who tried to restore order were brutally assaulted…

One thing is now certain. If the mutinous police had any public sympathy before Saturday, they have none now. Their only friends are the hoodlums and criminals. All decent-minded people stand aghast at the display of vandalism and crime which took place on Saturday, and for which the mutinous police must take full responsibility. A cause which exposes life and property to the mercy of those who prey on society is no cause for any decent person to espouse, and those who shirk their duty will find that out to their sorrow.

‘Rioting and Looting in Melbourne – Police Strike Results in Unprecedented Scenes’, article published in The Age, 5 November 1923.

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

After a week of unrest the government passed a Public Safety Bill, which brought in a special force to replace the strikers - and by 6 November, it was all over. A royal commission later acknowledged the strikers' grievances, but dismissed their actions. They were never reinstated.

Men line up outside the Melbourne Town Hall to volunteer as special constables during the Police strike, 1923

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Police and 'specials' charge the rioters in Bourke Street during the Melbourne Police Strike, 1923.

Reproduced courtesy Herald Sun newspaper

Two-metre tall wooden barricades protect the ornate buildings on Collins Street during the Police Strike.

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

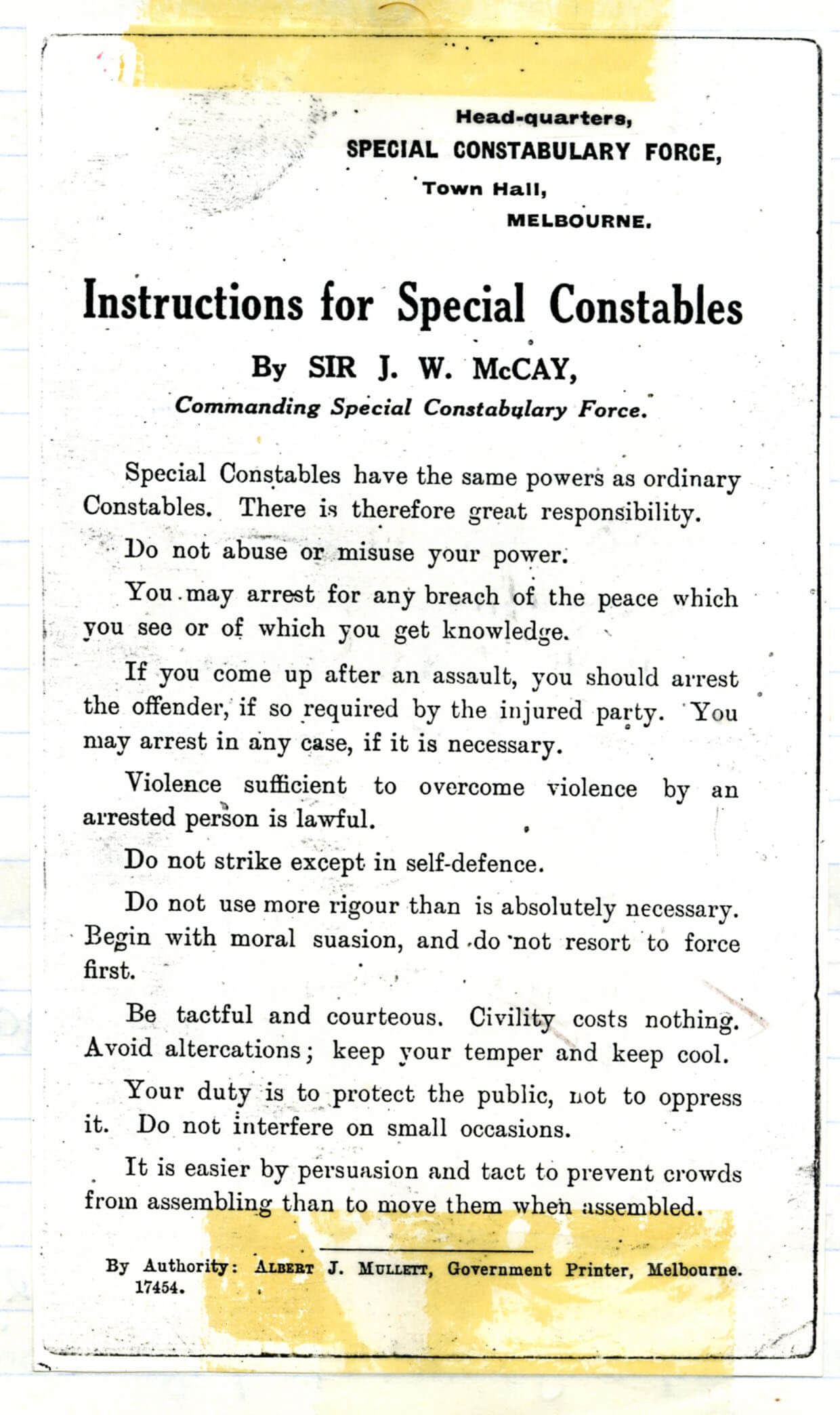

Instructions given to ‘special constables’ during the 1923 strike. Some 2,360 special constables were sworn in at Melbourne and suburban town halls.

Reproduced courtesy Victoria Police Museum

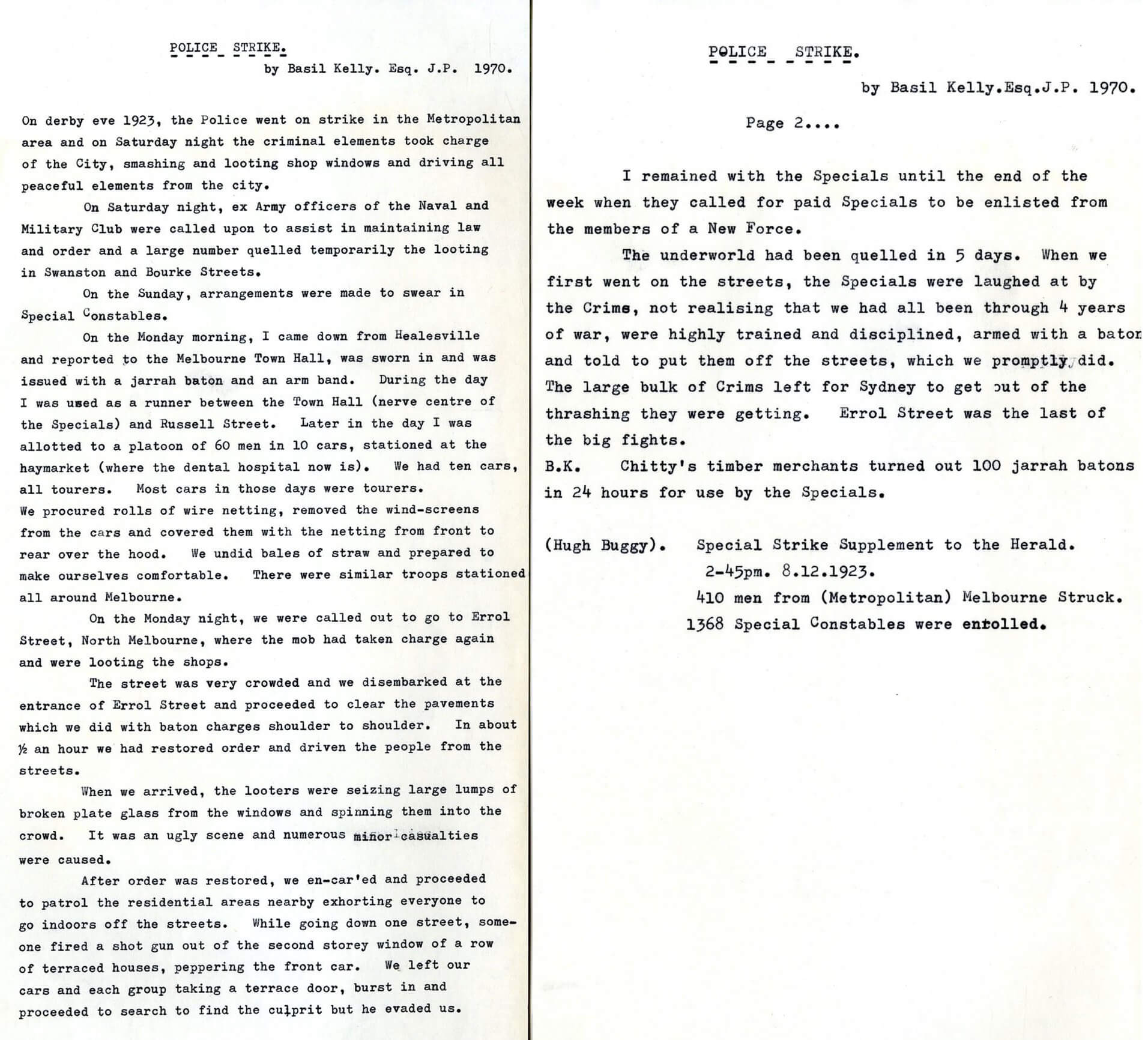

Basil Kelly was sworn in as a ‘special constable’ during the Police Strike in 1923. This is his first-hand account of events.

Reproduced courtesy Victoria Police Museum

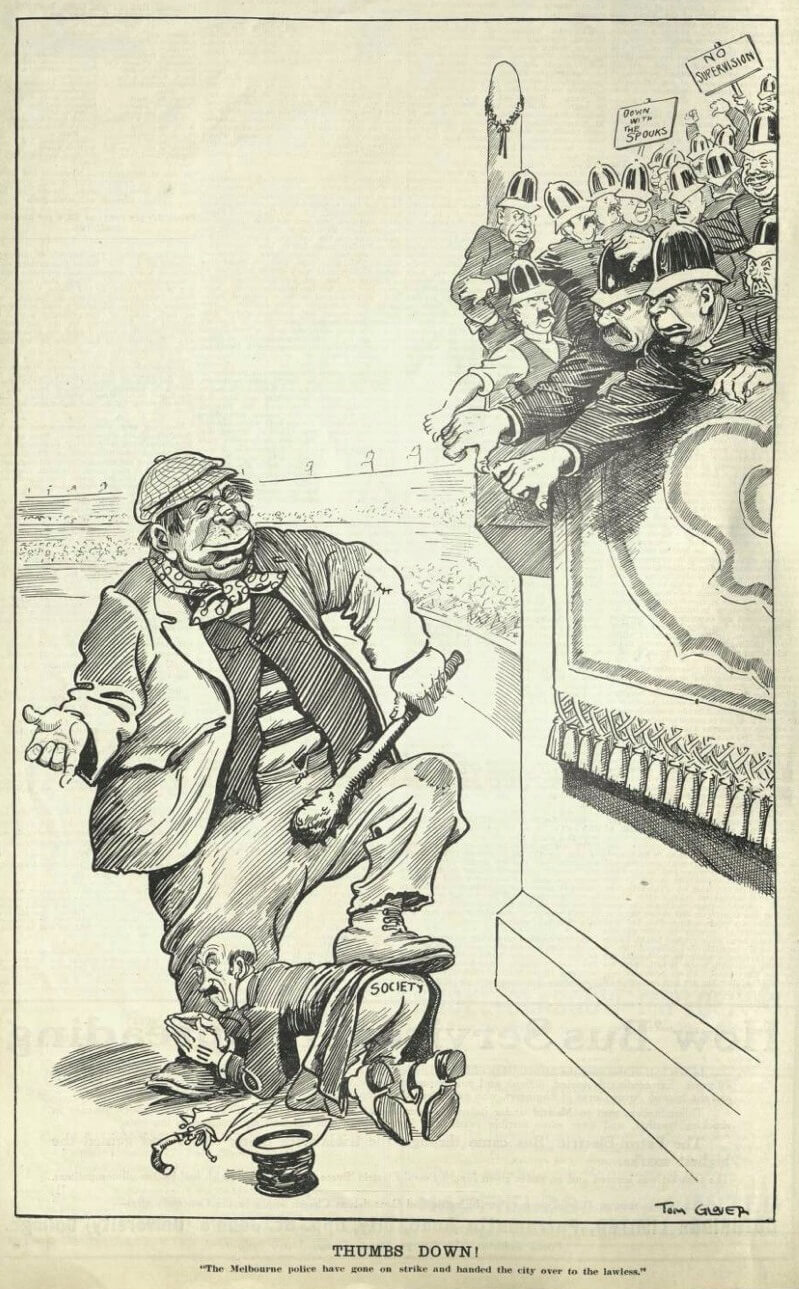

‘Thumbs Down! “The Melbourne police have gone on strike and handed the city over to the lawless”, cartoon published in The Bulletin, 8 November 1923.

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

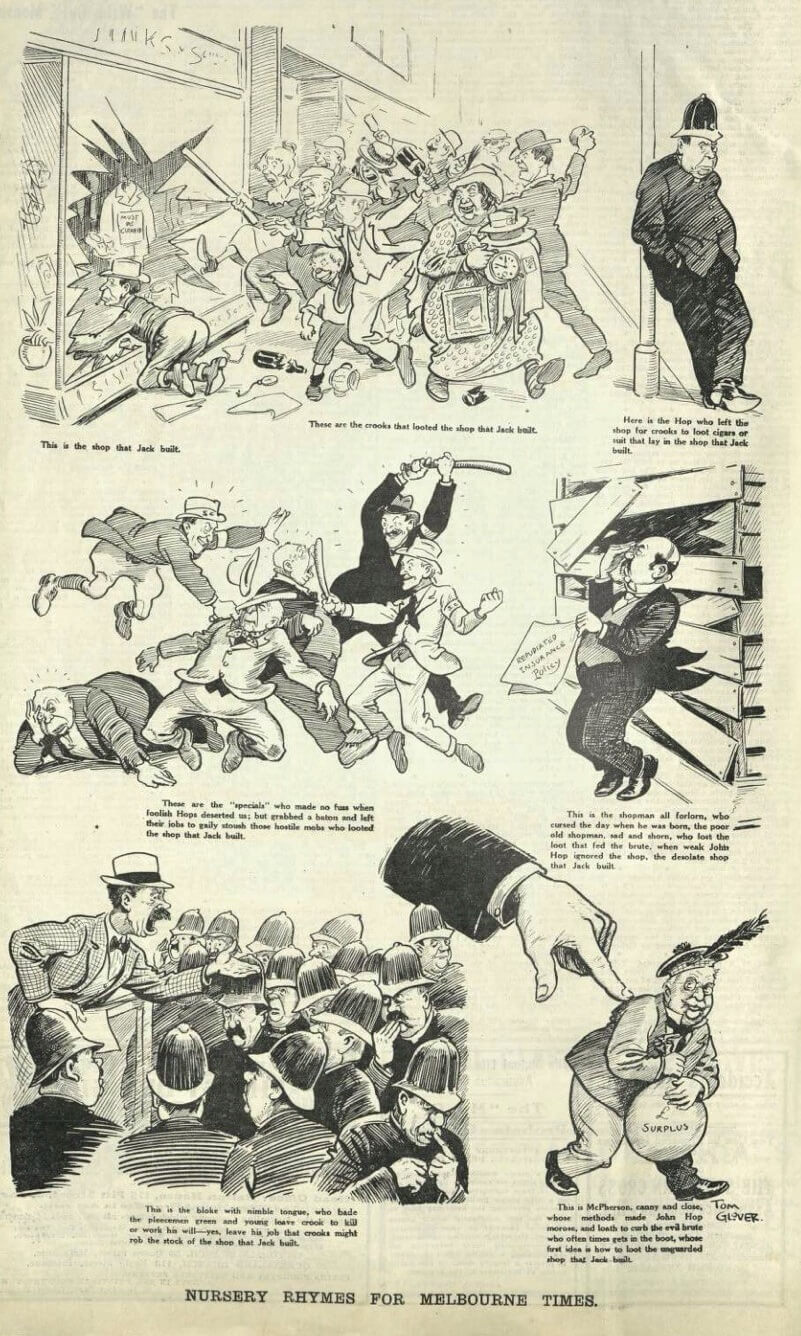

‘Nursery Rhymes for Melbourne Times’, cartoon published in The Bulletin, 15 November 1923.

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

The waterfront

The waterfront has long been a focus of industrial unrest. Insecure employment, combined with hazardous working conditions, fuelled discontent.

1890 Maritime Strike

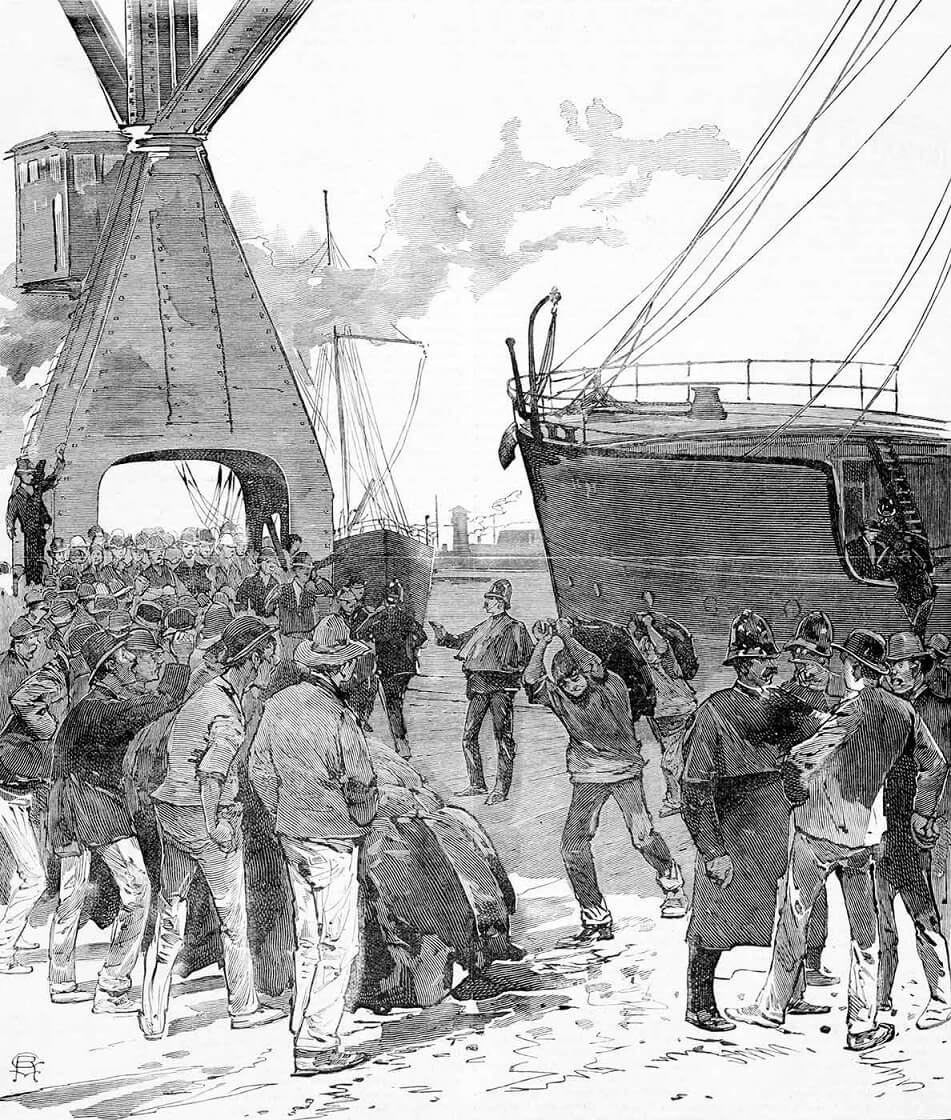

Union members struck in August 1890, resulting in ‘the largest, most violent industrial actions seen in Australia’. This strike was not over wages, conditions or working hours. For the workers, it was the freedom to join unions and restrict work to union members: for the ship owners, it was the right to employ non-union labour.

Strike action soon spread to include miners, labourers, railwaymen, shearers and storemen, with more than 50,000 workers across Australia involved. The strike paralysed Melbourne’s ports, the state’s coal mines, pastoral stations and industry. Melbourne was ‘plunged into darkness’ when coal deliveries from New South Wales were stopped and refineries could not provide street lighting.

Scenes got ugly at the Railway Pier in October when a group of men confronted non-unionists waiting to unload a German steamer. Shouting ‘we will give you blacklegs something for your trouble’, they allegedly attacked the men with ‘sticks, stones… almost anything that came handy.’

By the end of the year, the unions had been defeated. A deepening depression saw widespread unemployment, destroying the bargaining power of the unions. (At the height of the depression as many as one third of wage-earners were out of work.) The maritime workers agreed to their employers’ terms and went back to work. It was, however, ‘the most serious industrial dispute in Australian history’ – and a watershed moment in Australia’s political history. The formation of the Australian Labor Party followed from the realisation that combined union and political action was essential for change.

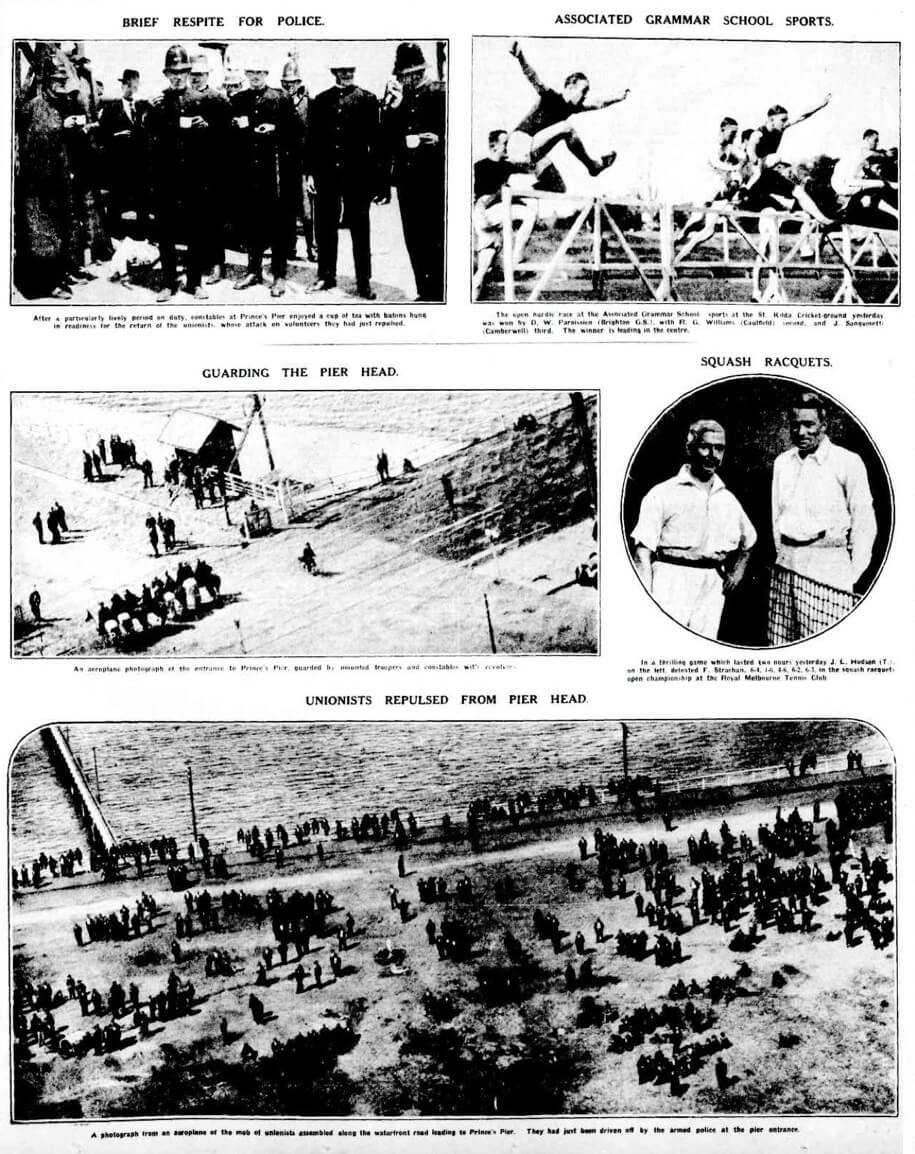

The 1890s strike was one of many waterfront protests. In 1919 a seamen's strike ‘brought shipping around Australia to a standstill’, and hundreds of Melbourne workers were stood down. In 1928 watersiders went on strike when employers attempted to introduce new hiring practices. Non-union labour - Italian and Greek migrants and volunteer university students untrained for waterside work - was brought in to man the wharves and piers. Unionists picketed the piers, threw stones at barges carrying ‘scab’ labourers down the Yarra River to work and jumped a train at Flinders Street Station carrying ‘volunteer’ passengers. At Prince’s Pier, it got violent. Watersiders threw stones at police. The police charged the men with batons, and fired their guns into the air. Four union members were wounded. Alan Whittaker, shot in the neck, died later in hospital.

Wharf ‘scab’ labourers working under police protection during the 1890 Maritime Strike.

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

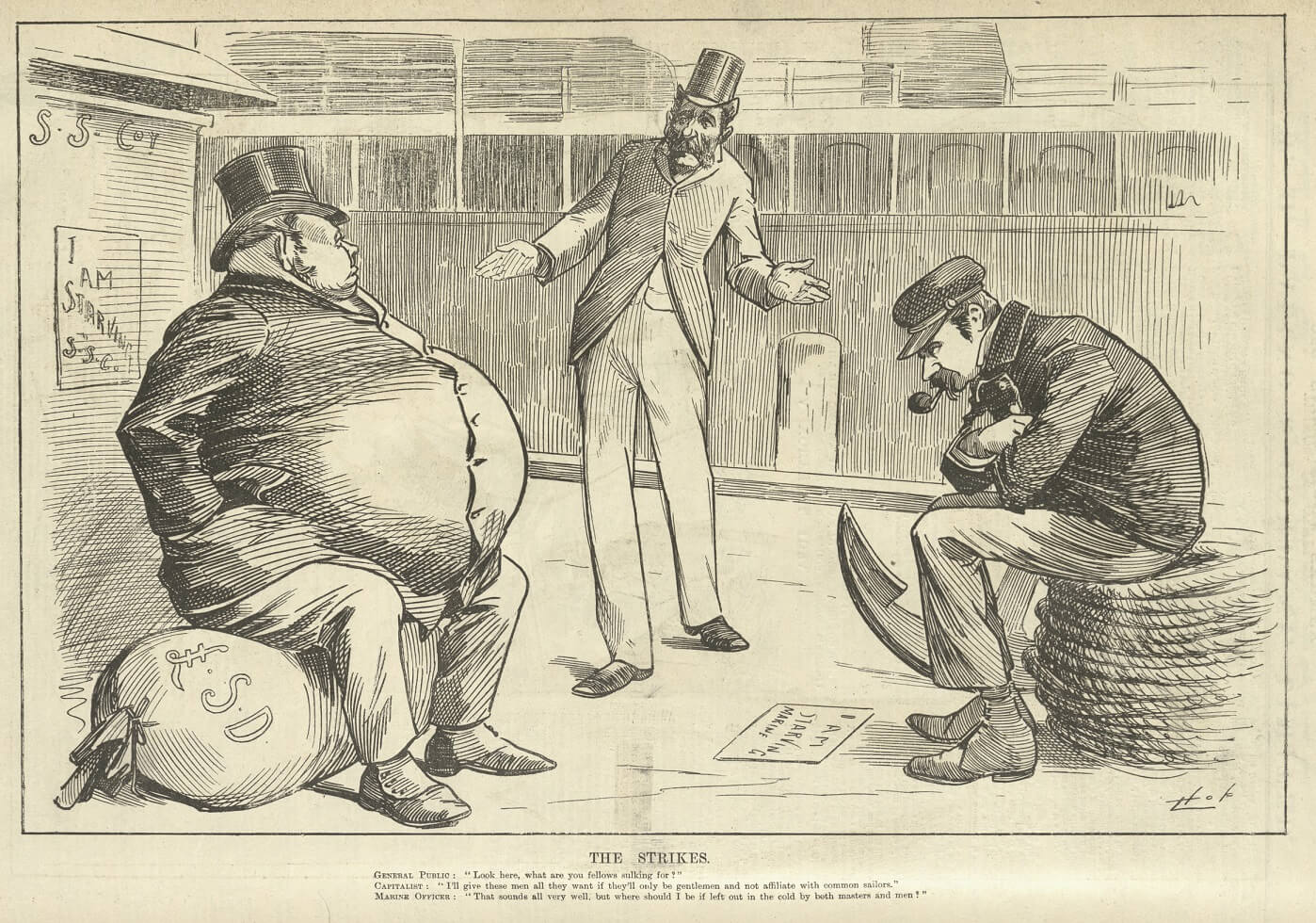

‘The Strikers’, cartoon published in The Bulletin, 23 August 1890

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

More recent times

Public protest continues to play an important role in the struggle for workers’ rights.

In November 1992, a crowd of about 100,000 people gathered outside Parliament House in Melbourne, protesting changes brought in by Liberal Premier Jeff Kennett. These changes included the closure of government schools, employment contracts outlawing penalty rates, leave loading and strikes, and privatisation of essential services. Protesters were drawn from a wide spectrum - from the more radical manufacturing and construction unions, to ‘white collar’ unions such as journalists and the Australian Teachers Union.

In 2006, workers again took to the streets, protesting the Liberal Howard government's Work Choices package. This legislation ignited fierce debate, facing strong opposition from both unions and the public. Workers’ conditions and rights were hard-fought and many opposed the new laws, which removed many formerly-compulsory conditions and ‘unfair dismissal’ protection. Across the country, an estimated 500,000 workers participated in rallies. The largest mobilisation took place in Melbourne on 15 November 2005, when 150,000 people marched. WorkChoices was repealed by an incoming Labor government in 2009.

Workers strike! Anti-Kennett Government rally, 1992

Reproduced courtesy The Age newspaper

Workers protesting the introduction of the Commonwealth Government’s Industrial Relations legislation, WorkChoices, Federation Square, Melbourne, 15 November 2005.

Reproduced courtesy The Age newspaper

Author: Ann Wilcox

Further Reading

Hamilton, Clive, What Do We Want? The Story of Protest in Australia, National Library of Australia Publishing: Canberra, A.C.T., 2016

Hocking, Geoff, Under the Southern Cross: the rebels, martyrs, exiles and activists who shaped Australia, Five Mile Press: Scoresby, Victoria, 2012

Sparrow, Jeff & Sparrow, Jill, Radical Melbourne, Vulgar Press: Carlton North, Victoria, 2001

Turner, Ian, In union is strength: a history of trade unions in Australia, 1788-1983, Nelson: Melbourne, 1983

Formation of the Labor Party- National Museum Australia