Anti-war protests have a long history in Melbourne. The Melbourne Peace and Humanity Society (PHS) was formed here in May 1900 by Dr. Charles Strong, Reverend Laurence Rentoul and H.B. Higgins. It was the first such organisation in Australia.

World War I

Even amid the fervent nationalism of the early years of World War I there were those who called for peace. Campaigns led by an alliance of peace and women’s political groups, with later help from the city’s Catholic Archbishop Daniel Mannix, helped defeat two referendums on conscription (compulsory military service) in 1916 and 1917.

The inter-war years

The inter-war years saw a strong move towards internationalism, with the formation of the League of Nations in 1919. Organisations such as the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) remained active throughout this time and in the decades after World War II. Towards the end of the war they campaigned on terms of surrender and peace negotiations. The bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan in 1945 initiated a strong anti-nuclear movement.

Post-war peace

A looming Cold War and the threat of nuclear weapons galvanised the peace movement after the Second World War. In May 1960, Australia’s first Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) group was formed in Melbourne and they organised annual marches at Easter. Groups such as Greenpeace, the Australian Nuclear Disarmament Party, and the Australian Greens have continued to champion the cause.

An elderly woman and young child attend a peace rally in Melbourne in the mid-1960s. The woman carries the modern peace sign, designed in 1958 by Gerald Holtom for the British Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. The inscription on the back reads ‘We both need peace’.

Photograph reproduced courtesy University of Melbourne Archives

The peace movement in the 1960s focussed on nuclear disarmament and opposition to weapons testing, in both Australia and the Pacific. (British nuclear testing, using Australian uranium, occurred at Monte Bello Island off the northwest coast of Australia and at Emu Field and Maralinga in South Australia.) Anti-nuclear demonstrations took place at Easter, the anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima (6 August), and the traditional labour holiday of May Day.

‘Hell no, we won’t go’!

Australia was involved in armed conflict in Vietnam from 1962-73. Always an unpopular commitment, opposition increased significantly when the Government introduced conscription, the National Service Scheme, in November 1964. Young men about to turn 20 had to register for national service (‘the draft’). Twice each year, dates were drawn. Those whose birthdays were drawn served two years in the army, unless they could convince a court that they were ‘conscientious objectors’. Objectors had to prove their opposition to all war, not just Vietnam.

Between 1965 and 1972 more than 800,000 men registered. About 63,000 were conscripted, and more than 19,000 served in Vietnam.

The issue of compulsory military service (conscription) proved hugely divisive, as it had during the First World War.

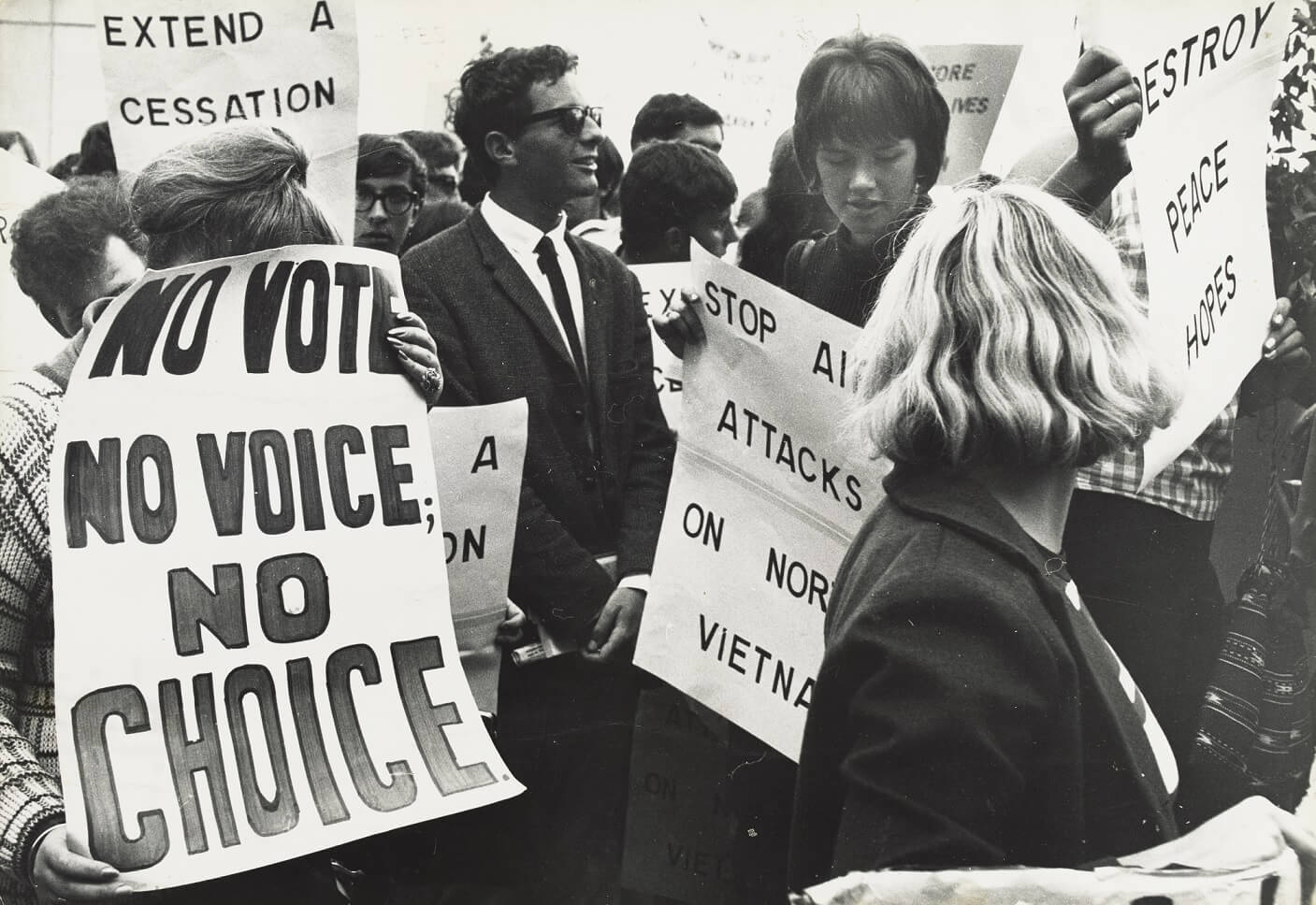

Anti-conscription demonstration held in Melbourne in 1965 while the ‘birthday ballot’ was drawn.

Photograph reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

The Youth Campaign Against Conscription and the Save Our Sons movements were both established in Melbourne in 1965. They participated in marches, meetings, ‘sit-ins’ and public rallies.

Protestors demanding the release of the ‘Fairlea Five’

Photograph reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Save our Sons (SOS) was formed in 1965 by mothers of teenage sons.

SOS members initially stood out as respectable voices of middle-class dissent in their sensible shoes, hats and gloves, but as the war dragged on some became more radical- staging sit-ins at government buildings, chaining themselves to Canberra’s Parliament House, wearing anti-war fashions to the Melbourne Cup, hijacking an evangelical rally, and organising an ‘underground’ to hide draft resisters.

In April 1971 five SOS members were sent to Fairlea Women’s Prison in Melbourne for handing out anti-conscription leaflets in a National Service office. They were arrested under a charge of Wilful Trespass. The ‘Fairlea Five’ became the first civilians charged under the Summary Offences Act of 1971, which limited the rights of protesters, including acts of obstruction and trespassing.

The case received wide publicity, the media emphasising the imprisoned women’s role as parents.

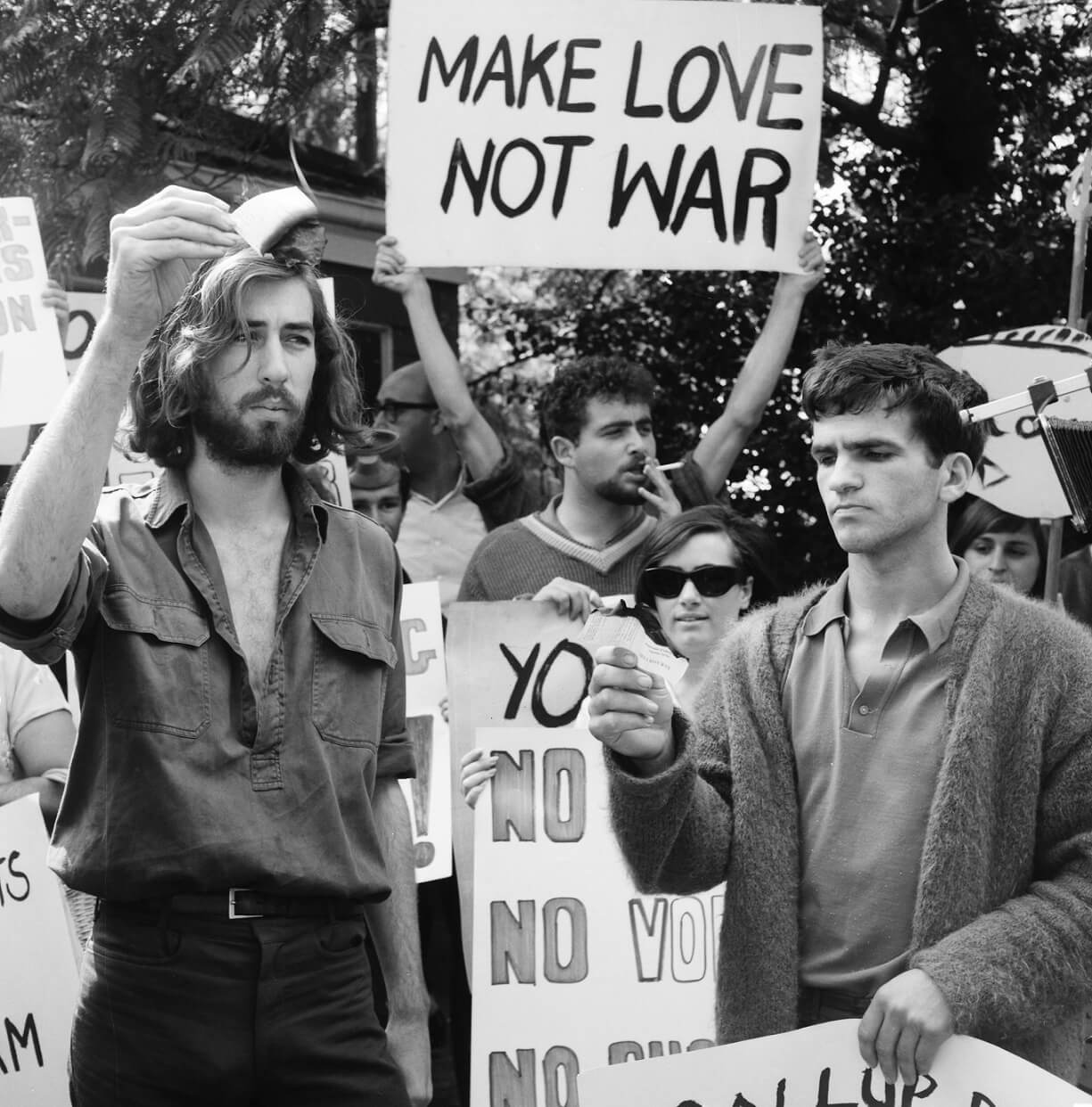

Anti-conscription protest, Melbourne

Photograph reproduced courtesy The Age newspaper

Resistance was led by a growing student ‘New Left’ movement. In March 1966 Andy Blunden burned his national service registration card outside the Melbourne home of Prime Minister Harold Holt.

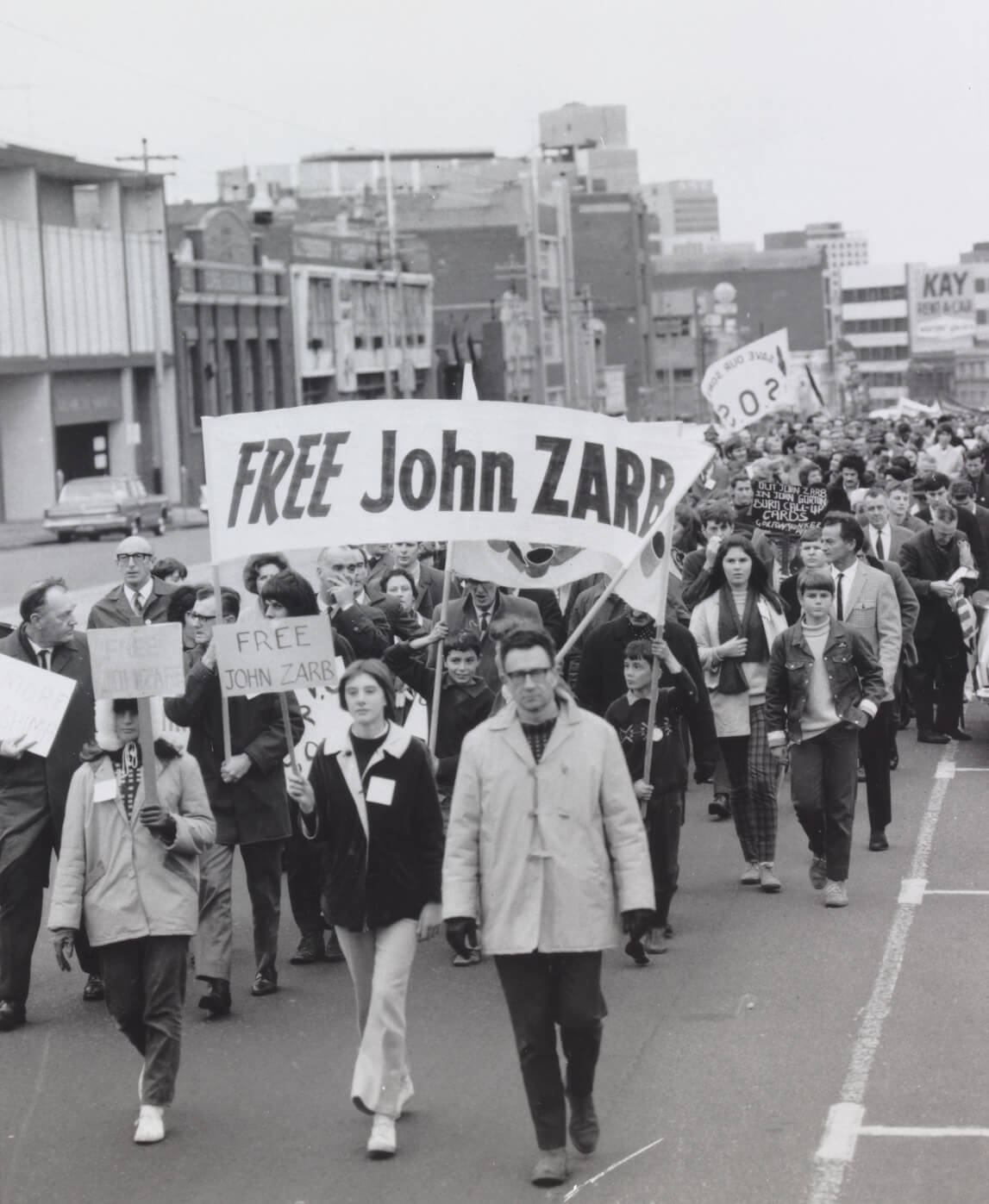

Protesters march down Sydney Road towards Pentridge Prison in support of John Zarb, imprisoned for two years for refusing to enlist.

Photograph reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

John Francis Zarb, a 21-year old postal worker and student, was the first man convicted for failing to comply with his call-up. He was gaoled for non-compliance under the National Service Act. Zarb had applied for registration as a conscientious objector. The magistrate accepted his opposition to Vietnam, but not to war in general.

Zarb was sentenced to two years imprisonment in October 1968, but served only 10 months. His release on compassionate grounds followed sustained protest.

Protests reached their peak with the moratorium movement, led by Labor politician Jim Cairns. On 8 May 1970, 100,000 people gathered in Melbourne’s streets - more than twice the number of any other city.

Photographer Bruce Postle captured the first Vietnam moratorium march in Melbourne from the Manchester Unity Building.

Photograph reproduced courtesy The Age newspaper

By 1968 the Vietnam War had escalated. Media coverage, particularly television, exposed the public to scenes of civilian suffering and brutality.

Opposition to an ‘unwinnable war’ mounted and in Melbourne, in early 1970, anti-war groups from across Australia agreed to hold a moratorium - a ‘halt to business as usual.’

On 8 May 1970 up to 100,000 people marched down Bourke Street in Melbourne. The smaller second and third moratoriums took place on 18 September 1970 and 30 June 1971.

Crowd demonstrating at a moratorium march on the steps of the Old Treasury Building, Melbourne, 1970/71.

Photograph reproduced courtesy Australian War Memorial, AWM POO671.003

Did the moratoriums affect the Government’s decision to withdraw troops from Vietnam? Prime Minister John Gorton had started to withdraw troops in 1970 and Gough Whitlam escalated this in 1972. But the moratoriums certainly emphasised changes in social attitudes.

Not since the conscription referendums of the First World War had there been such widespread and passionate social and political dissent. Families divided, with draft resisters, protestors and conscientious objectors being gaoled, and conscripts and regular soldiers sometimes facing hostility. The moratoriums became one of the defining moments of the baby-boomers’ generation.

The Vietnam War was the most divisive issue in Australia since the conscription referendums of World War I. And for those who served in the Armed Forces, it was not soon forgotten. Many veterans suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder and found it difficult to return to civilian life. Some joined the anti-war protests when they returned: others found them deeply upsetting.

More recently

Since the 1970s peace organisations have formed (and disappeared) in response to events. Uranium mining, US military bases, French and British atomic testing initiated nuclear disarmament protests. Wars in the Gulf (1990) and Indonesia’s attempt to annex East Timor, brought Melburnians out on the streets, as did the 2003 Iraq War – which saw the largest protests since the Vietnam moratoriums.

USS Queenfish protest, Station Pier, Port Melbourne, 5 March 1978

Photograph reproduced courtesy University of Melbourne Archives

By the 1970s anti-nuclear campaigns revolved around the issues of uranium mining and nuclear testing, US military bases and nuclear ship visits and the creation of a nuclear-free zone in the Pacific. Australia was, and is still, one of the world’s largest exporters of uranium.

In 1978 peace activists and anti-nuclear campaigners assembled at Station Pier in Melbourne, protesting the arrival of the USS Queenfish, the first nuclear-attack submarine to visit an Australian port. Police and protesters clashed and several people were injured and arrested.

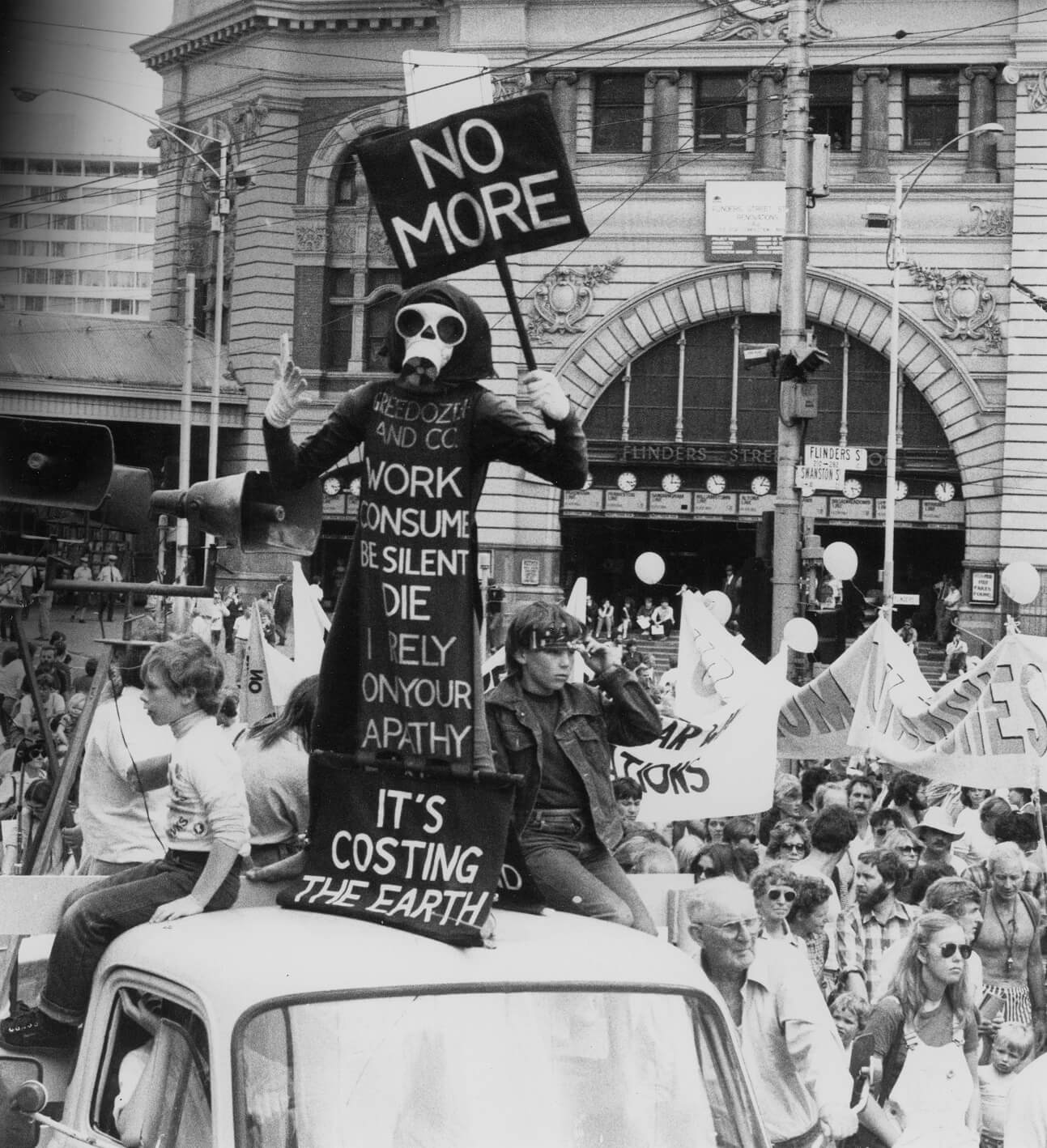

Palm Sunday rally outside Flinders Street Station in Melbourne, 1984

Photograph reproduced courtesy University of Melbourne Archives

Anti-nuclear protests embraced many issues - disarmament, the global weapons race, harm to the environment, the ethical and health-related impact of nuclear testing on First Nations communities and security risks.

Throughout the 1980s the anti-nuclear movement maintained a presence through marches, notably the annual Palm Sunday rally. One of the largest was in 1985, when more than 300,000 people marched across Australia.

Benny Zable at the Palm Sunday Rally, April 1984

Photograph reproduced courtesy University of Melbourne Archives

Peace activist, Benny Zable, has protested in Melbourne for three decades. Zable created a caricature costume of the grim reaper: ‘I visualised a dark character with a skull head, “Greedozer”, to portray the ugly side of civilisation.’

Melbourne protests Australia’s involvement in the Iraq War, 2003

Photograph by Francis Reiss. Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

In February 2003 up to 150,000 people marched through Melbourne protesting Australia’s involvement in the Iraq War. It was Melbourne’s largest-ever peace rally.

These protesters were not alone. In all some 6 million people marched, in more than 600 towns and cities across the world.

Author: Ann Wilcox

Further Reading

Judith Smart, 'Anti-War and Peace Movements', online Encyclopedia of Melbourne.

Hamilton, Clive, What Do We Want? The Story of Protest in Australia, National Library of Australia Publishing: Canberra, A.C.T., 2016

Langley, Greg, A decade of dissent: Vietnam and the conflict on the Australian homefront, Allen & Unwin: North Sydney, 1992

Saunders, Malcolm & Summy, Ralph, The Australian Peace movement: a short history, Peace Research Centre, Australian National University: Canberra, 1986

Sparrow, Jeff, Radical Melbourne 2: the enemy within, Vulgar Press: Carlton North, Victoria 2004

Exhibition catalogue – We Protest! / curator Malcolm McKinnon. Shown at City Gallery, Melbourne, 2018