From the very beginning Aboriginal Victorians have fought to retain their land and their culture. In the first decades after the European invasion access to water and land was the primary issue. Later, leaders like William Barak began to focus on political rights and the right to self-determination. In the twenty-first century, these issues are still unresolved.

Exclusion

As the scale of the European invasion became apparent, some First Nations Victorians took up arms to defend their access to water and hunting grounds. They were soon overwhelmed by superior weaponry and by the sheer number of the invaders. Within a few years the fragile food supplies that had sustained groups for generations were depleted, but Europeans refused to compensate by sharing their herds and flocks. Attempts to spear stock for food led immediately to accusations of theft and retribution.

In 1840 the Woi wurrung and Boon wurrung were even excluded from the town of Melbourne, on the express orders of Governor Gipps and Superintendent Charles La Trobe. The newly-appointed Protectors of Aborigines were instructed to ensure that the governor’s decree was enforced, and by 1850 most of the Kulin were forced to live on designated missions and reserves.

The ‘Coranderrk rebellion’

But even these meagre reserves were not safe. The first ‘mission’ was established on the south bank of the Yarra near the present site of the Botanic Gardens, but this land was soon considered to be too valuable for such a use, and the land was resumed. It was to be a common pattern for land set aside for the use of First Nations people. In fact the first documented ‘protest’ by First Nations Victorians took place in 1876 in response to plans to close the reserve at Coranderrk, located on the banks of the Yarra River near present-day Healesville. William Barak, ngurungaeta (leader) of the Woi wurrung, marched a delegation of men from Coranderrk over 60 kilometres to Melbourne to see the Chief Secretary. They persuaded Chief Secretary James McCulloch that Coranderrk should be retained, but better managed.

The Aboriginal Protection Amendment Act, 1886

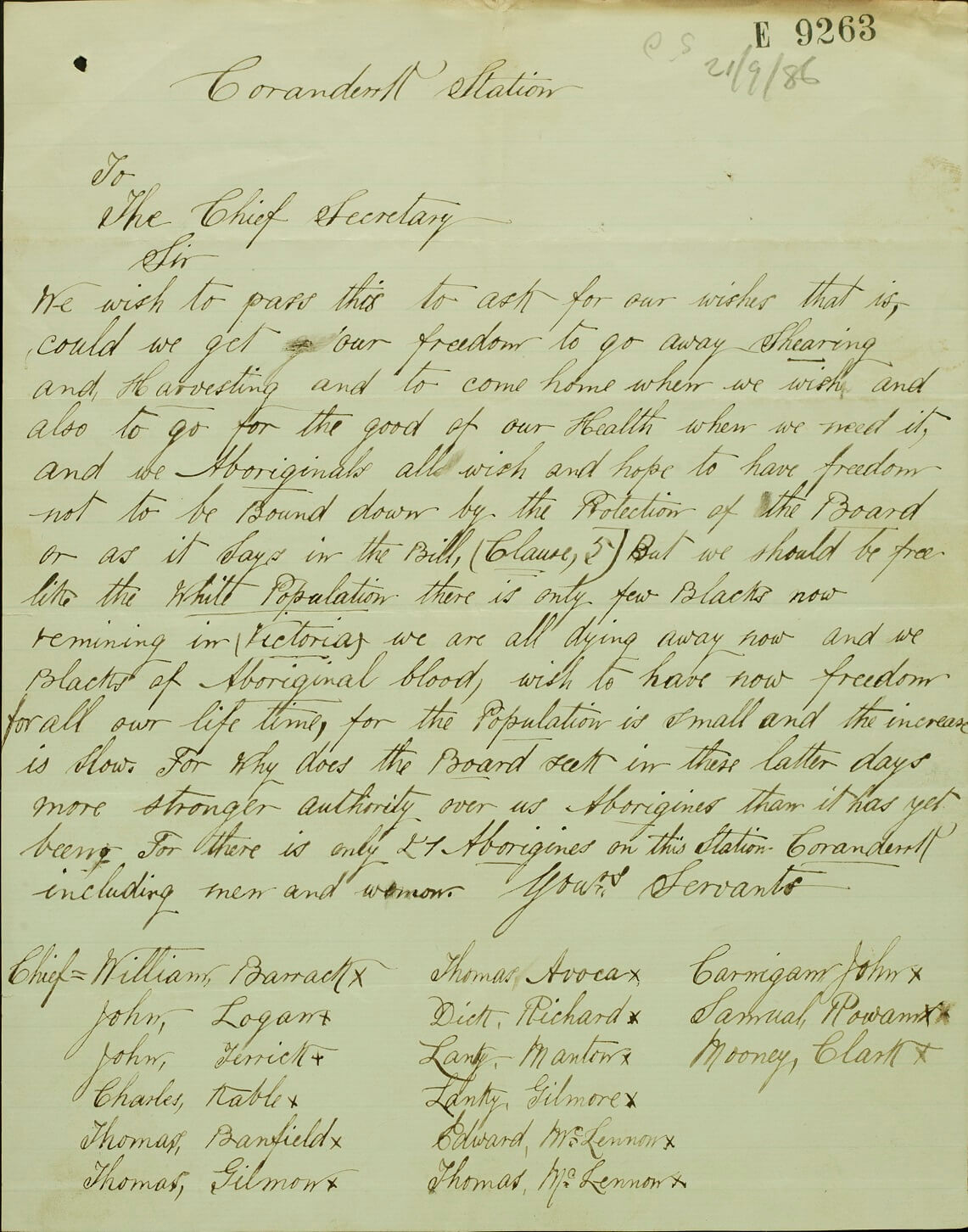

Barak led a second delegation to see Chief Secretary Duncan Gillies 10 years later, opposing aspects of a new law, the Aboriginal Protection Amendment Act, 1886 (Vic). The 1886 Act defined ‘Aboriginal’ people in terms of race, rather than culture, part of its aim being to exclude so-called ‘half-caste’ (mixed race) people from living on the reserves. This was designed as a cost-saving measure, but effectively separated families. It also began the systematic removal of children of mixed descent from their families. In a signed petition dated September 1886 Barak and the other petitioners sought the right to travel on and off the reserve for work, and informed Gillies: ‘we Aboriginals all wish and hope to have freedom…we should be free like the White Population.’ Barak organized other similar petitions to government seeking the retention of Coranderrk and protesting against the Act. He was a remarkable leader, who did his best to use the mechanisms of the democratic process to help his people.

Petition to the Chief Secretary from Coranderrk Station.

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

The long fight for citizenship

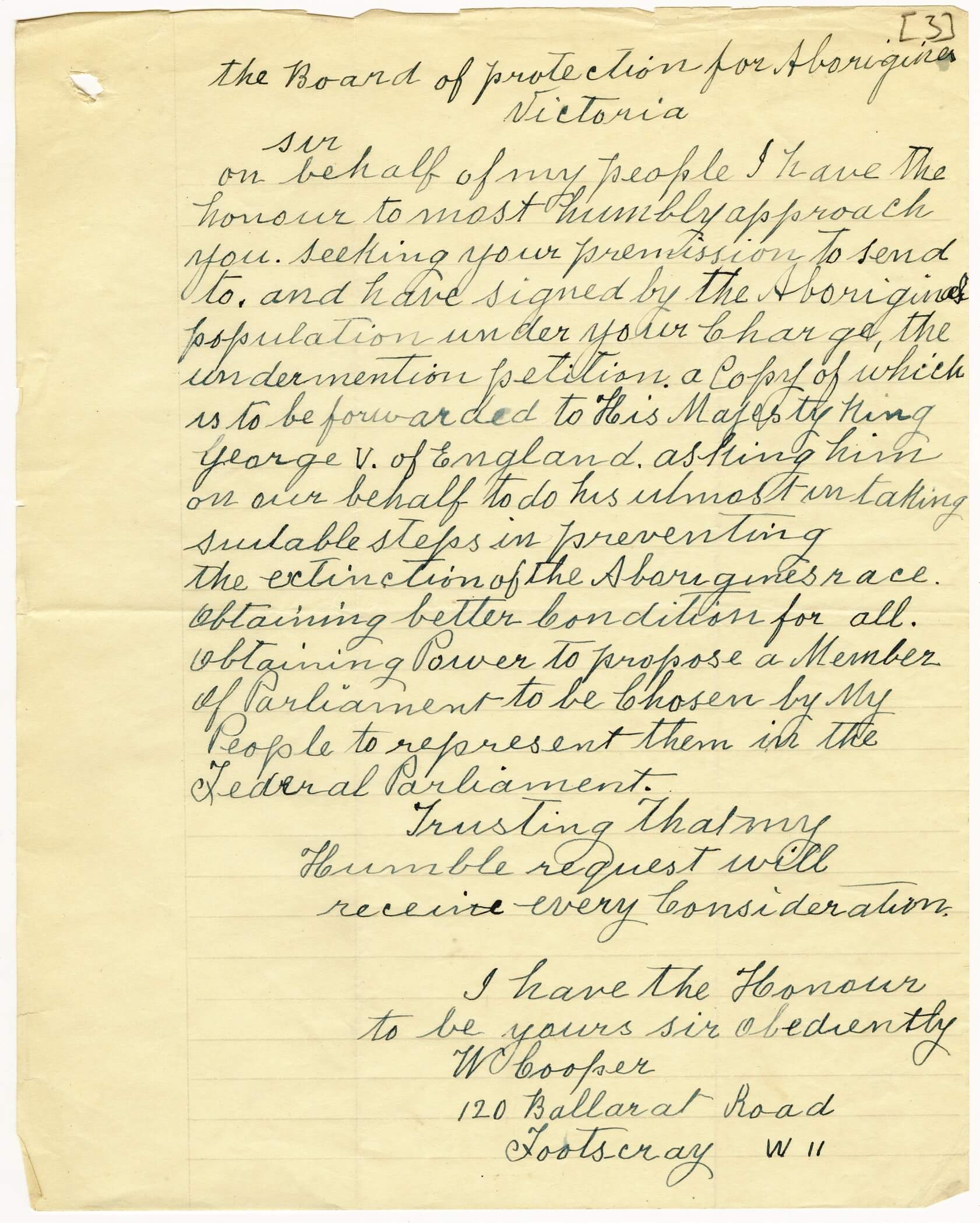

Barak’s death in 1903 deprived First Nations People in Victoria of a redoubtable leader, but in the following decades others emerged to take his place. By the 1930s First People had reclaimed the right to live in Melbourne and an identifiable community formed in the inner-city suburbs of Fitzroy and Footscray. It was there in 1933 that Yorta Yorta man William Cooper and others formed the Australian Aborigines League to fight for ‘a fair deal for the dark race.’ They campaigned for equal political rights and for the repeal of discriminatory legislation. In 1937 they tried to petition King George V for direct representation in the Parliament of Australia, and sought his ‘utmost’ in ‘taking suitable steps to preventing the extinction of the Aborigines race’. Their petition was signed by 1,814 First Nations people, but the Board for the Protection of Aborigines refused to forward it to the king. The issue of direct representation for Indigenous people in the Parliament of Australia continues to resonate today.

The League’s work continued after World War II, led by Rev. (later Sir) Douglas and Gladys Nichols and Bill Onus. Their campaign for equal political rights gradually bore fruit: from 1949 all Indigenous people who had served in the armed forces were entitled to vote in federal elections, but the exclusion of others was not removed until 1962.

Letter from William Cooper seeking permission to petition King George V.

Reproduced courtesy National Archives of Australia

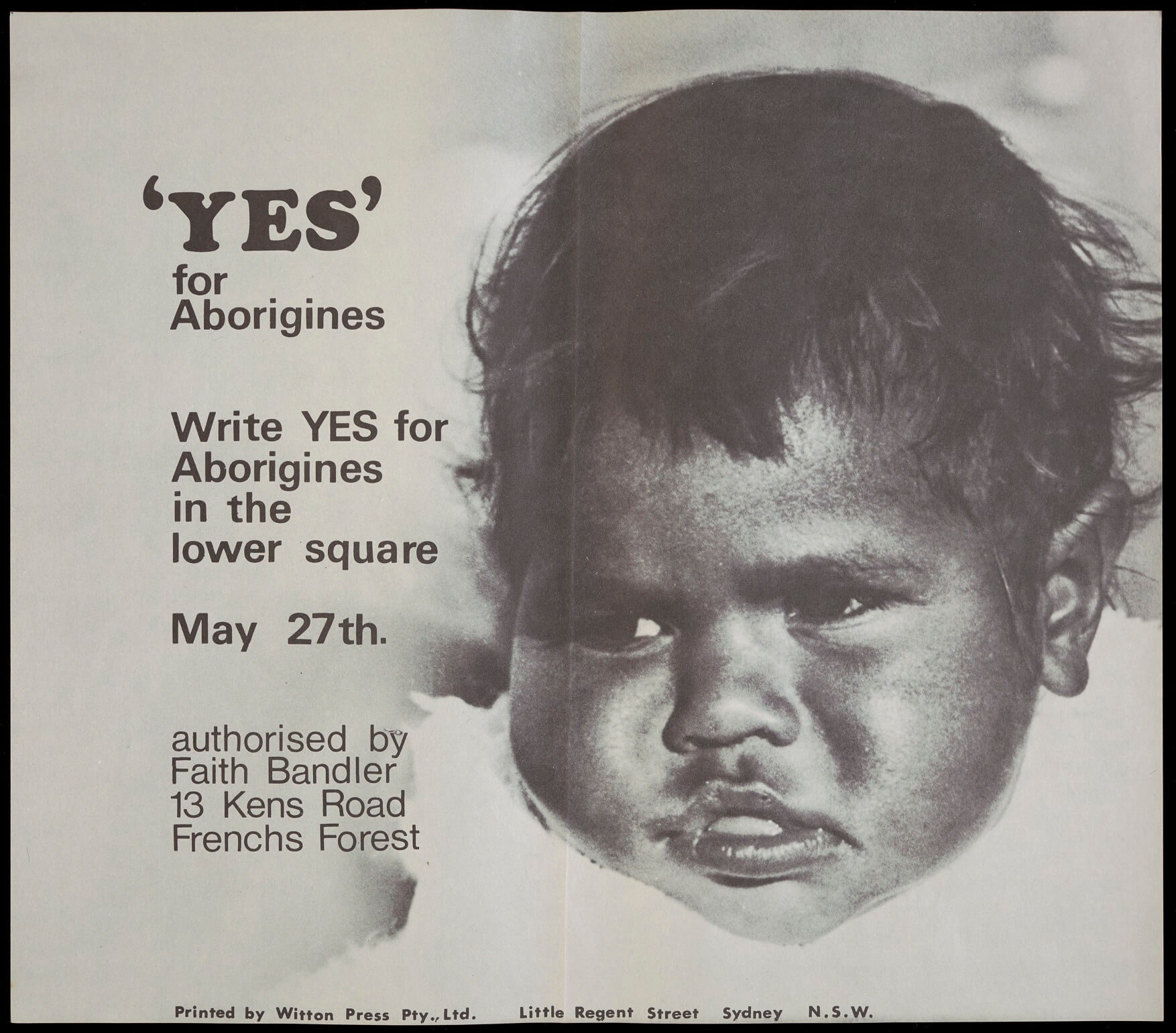

The 1967 referendum

Although from 1962 First Nations people were finally considered to be citizens of Australia, discrimination continued in many aspects of their lives. Restrictions were greater in some states than others. In 1967 the federal government held a referendum to transfer the power to legislate for Aboriginal Australians from the states to the Commonwealth: it also sought the power to include Aboriginal Australians in the national census. The referendum passed with a resounding majority – 91% voting in favour nationally and 95% in Victoria.

Iconic 1967 Referendum poster ‘Yes’ for Aborigines.

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Land rights

Recognition of Indigenous land rights was an issue of continuing resonance. First Nations people fought to retain their hold on reserves, against successive government attempts at resumption. In 1965 Rev. Doug Nicholls led a protest outside Parliament against the threatened closure of Lake Tyers reserve in Gippsland. The Lake Tyers reserve was home to former residents of Coranderrk, Ebenezer and Ramahyuck, all of which closed in the decades after 1904. The protest was ultimately successful and the mission was declared a permanent reserve. In 1970 the Aboriginal Lands Act 1970 finally recognised land rights in Victoria and the management of Lake Tyers was vested in the Lake Tyers Aboriginal Trust. Lake Tyers is also known as Bung Yarnda.

Pastor (later Sir) Douglas Nicholls leads a protest against the threatened closure of Lake Tyers Aboriginal Settlement, March 1965

Reproduced courtesy The Age newspaper

However the general issue of land rights has continued to be a focus of First Nations protest.

Aboriginal Land Rights protest, Collins and Spring Streets Melbourne, 1971

Reproduced courtesy The Age newspaper

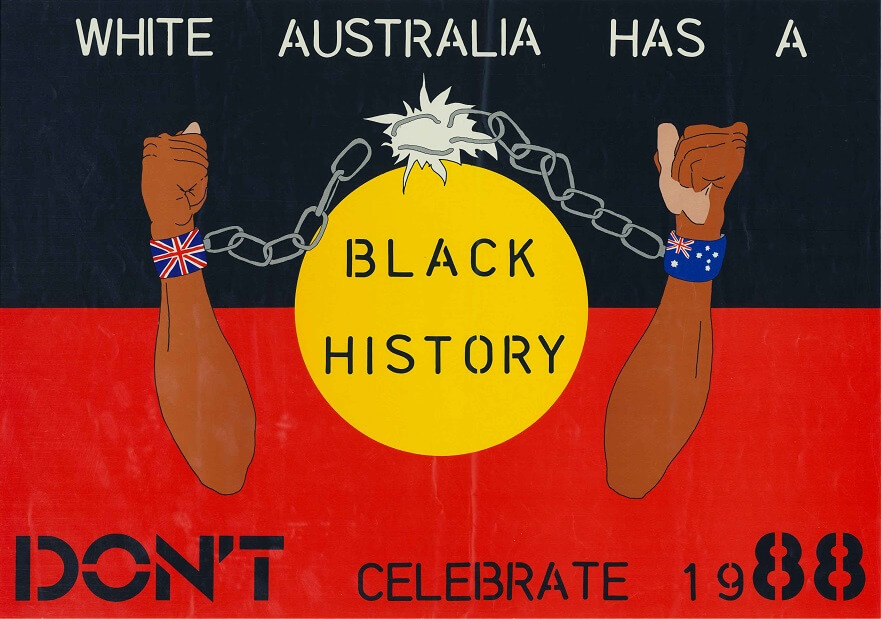

White Australia has a black history

Along with land rights, a recurring focus of First Nations’ protest has been the better recognition of black history. The celebration of Australia Day on the date that the First Fleet arrived in Botany Bay has been especially contentious. Again, this is an issue with a long history. The Australian Aborigines League held the first Invasion Day protest as early as 1938, at the time of the sesqui-centennial celebrations, and it has continued ever since. One of the most successful slogans has been ‘White Australia has a Black History’. Used to great effect during the celebrations marking the bicentenary of European settlement in 1988, it continues to resonate. As a nation we have yet to find an alternative, more inclusive date to celebrate our national day.

White Australia has a Black History poster, c. 1988

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Invasion Day Rally, Melbourne 2017

Reproduced courtesy The Age newspaper

Black lives matter

Another significant issue to inspire black protest has been the disproportionate incarceration rate of Indigenous people and the tragic number of associated deaths in custody. The deaths continue, despite numerous enquiries into prisons and the police service, provoking anger in First Nations people. April 2020 marked 30 years since the Royal Commission into Black Deaths in Custody reported, prompting protests in commemoration. Then in May 2020 the murder in America of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer, sparked global protest. Rallies in support were held in many Australian cities, including Melbourne, despite lockdown regulations associated with the COVID pandemic. Protests in Australia expressed solidarity with the black community in the United States, but also highlighted the persistent local tragedy of black deaths in custody. ‘Black lives matter’ was the theme of these rallies.

Author: Margaret Anderson

Further Reading

Bain Attwood and Andrew Markus, Thinking Black: William Cooper and the Australian Aborigines’ League. Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 2004.

Richard Broome Aboriginal Victorians: a history since 1800. Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2005.