The first conscription referendum was held on Saturday 28 October 1916. Australian electors were asked to answer 'Yes' or 'No' to the following question:

Are you in favour of the Government having, in this grave emergency, the same compulsory powers over citizens in regard to requiring their military service, for the term of this war, outside the Commonwealth, as it has now with regard to military service within the Commonwealth?

The question was long and complex. There was no explicit mention of conscription. The reference to existing military service meant the requirement for compulsory military service within Australia for all men aged between 18 and 60, in existence since 1911.

The campaign

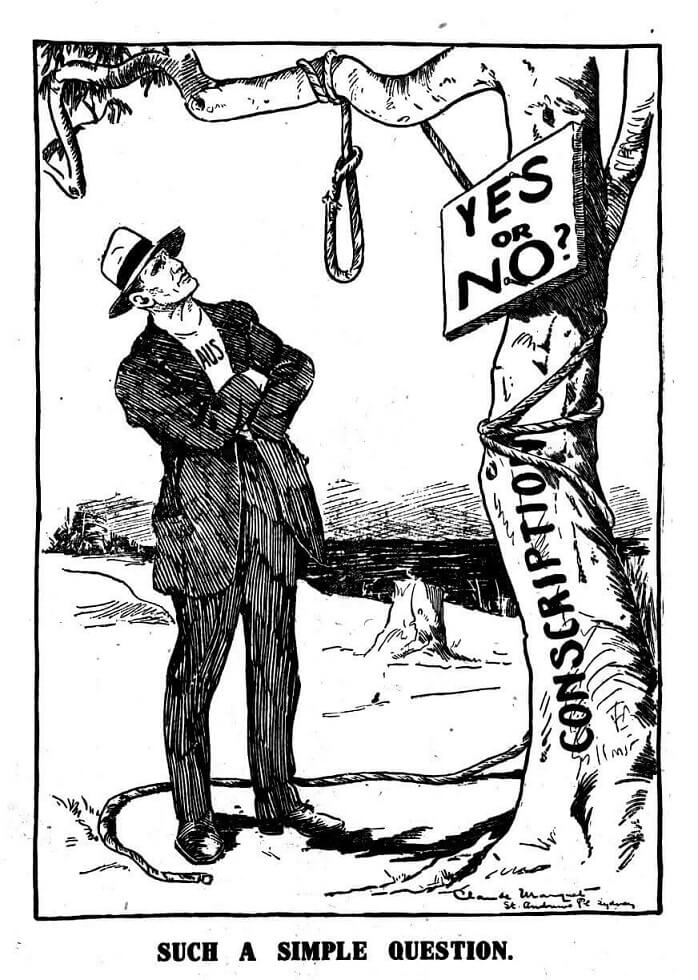

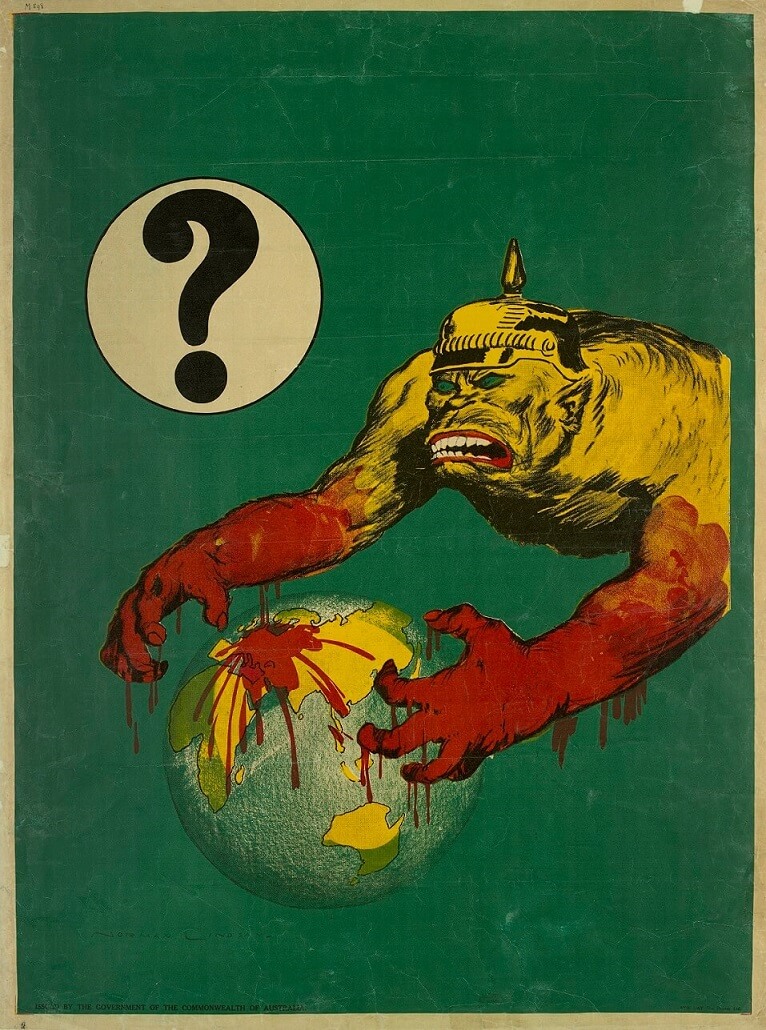

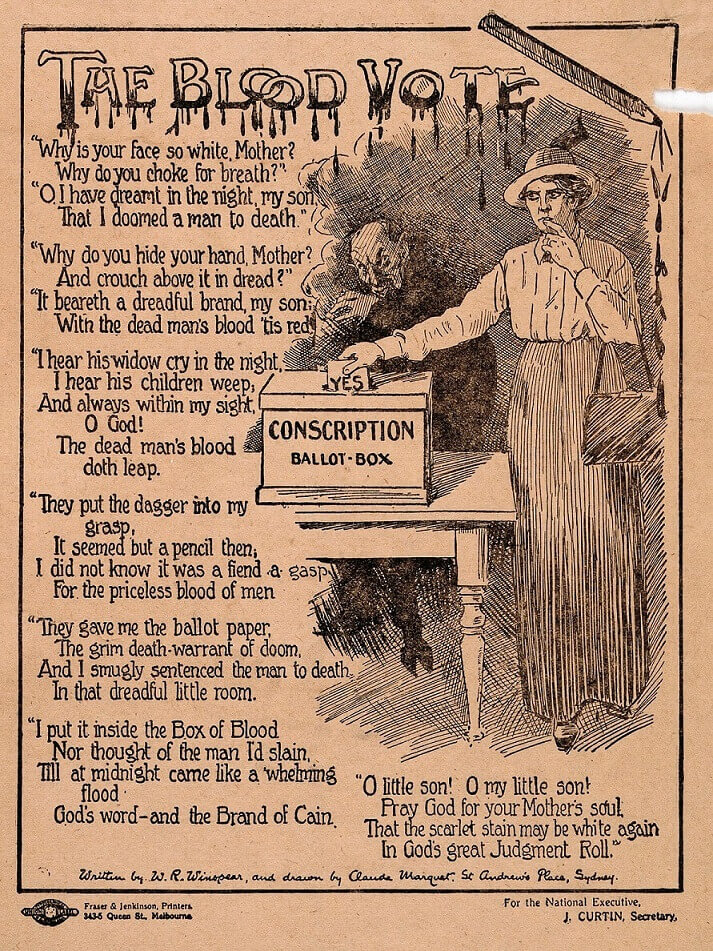

There were eight weeks of bitter campaigning before the vote. Since voting was not compulsory in 1916, either for the referendum or for elections, each side needed to persuade electors both to support their cause, and to turn out and vote. In the days before radio, public meetings and rallies were popular means of recruiting followers. Huge meetings, marches and rallies were held by both sides and noisy, even violent heckling was common. Women were not exempt from rough treatment. The marches organised by Vida Goldstein and Adela Pankhurst's Women's Peace Army were regularly disrupted by returned soldiers and others, and many marches ended in public brawls. Both sides made extensive use of graphic pamphlets, posters and cartoons, designed to appeal to patriotism, or inspire fear. Depictions of the enemy Germany were particularly gruesome, playing on grotesque stereotypes of the murderous 'Hun'.

Courtesy National Library of Australia

Image courtesy Australian War Memorial

Image courtesy National Library of Australia

The 'Yes' campaigners

The Australian Government was the main proponent of the 'Yes' case, although many government MPs actually campaigned against it. It was an extraordinary situation. Almost all of the daily press was in favour, and kept up a barrage of editorial content designed to persuade voters to support conscription. The Liberal Party supported conscription, as did many conservative organisations like the Australian Natives Association, or the Australian Women's National League. Most municipal councils (Richmond and Brunswick/Coburg were exceptions), employers' groups and Chambers of Commerce also supported the 'Yes' case. Many of these groups banded together in a newly formed National Referendum League. Generally the mainstream Protestant Churches seem to have favoured conscription, but some, notably the Quakers, opposed both conscription and the war on conscientious grounds. The Catholic hierarchy took no official stance in 1916, though many individual priests were thought to oppose the measure. Catholic bishops were divided.

The arguments in favour of conscription

Proponents of conscription appealed to voters' patriotism, their support for Empire and the Mother Country in its hour of need. Emotional appeals were made to defence of British 'liberty', seen as threatened by the rampant 'militarism' and 'tyranny' of 'Prussianism'. Much of the propaganda also centred on the need to help 'our boys at the front', who were depicted in graphic posters wounded and exhausted, appealing desperately for support from home. This was often an extension of the general recruitment campaign, which played on men's conscience, or sense of shame. 'Shirkers' were stigmatised for leaving others to fight for them while they languished at home. Women were targeted specifically, now that they had the vote. Propaganda appealed to womanly pride if their husbands or sons were soldiers, or shame if they were not.

Image courtesy Australian War Memorial

The 'No' campaigners

The 'No' campaigners faced extraordinary odds, pitted against the might of the government and national press combined. At the base of the 'No' campaign was organised labour and the labour press. Their resources were stretched to the limit, but they were highly organised, resolute, passionate and energetic. They also had the services of several very talented cartoonists, who created some of the most potent imagery of the campaign. Claude Marquet, who drew for various labour publications, created a series of graphic cartoons and posters, including the image on perhaps the most famous poster of the campaign - 'The Blood Vote'. The words were written by E.J. Dempsey, who ironically worked for a conservative newspaper, though attributed, perhaps for this reason, to W.R. Winspear. It is estimated that one million copies of this poster were distributed in 1916-17, to great effect.

Other groups who were important to the 'No' campaign included the radical Industrial Workers of the World - the IWW or 'Wobblies'. With other radical groups they formed the Anti-Conscription and Anti-Militarist League in Melbourne in July 1915. Although small in number, they were highly organised and adept at disrupting opposition meetings. They also enlivened many public meetings with rousing radical songs, including 'The Red Flag' and 'Solidarity Forever', both originating in America. Hughes saw them as seditious. Women's organisations like Vida Goldstein's Women's Peace Army, organised many large meetings and led mass rallies, supported by various other civil libertarian and anti-war groups and the Victorian Socialist Party. These rallies also featured singing. Especially popular was the American song 'I didn't raise my son to be a soldier'. This was so effective that the government declared it a 'prohibited song'.

The arguments against conscription

It is important to remember that opposition to conscription did not necessarily mean opposition to the war itself. Although there were anti-war groups, many who opposed conscription still supported Australia's involvement in the war. But they opposed compulsion on principle, arguing that it was the worst of all tyrannies. The 'No' campaigners also claimed to speak in the name of 'liberty' - the liberty of ordinary people to decide for themselves whether to fight and die. They argued that conscription was an expression of the very 'militarism' Australians were fighting in Europe.

The labour movement and the IWW also demanded what they called 'equality of sacrifice', believing that the burdens of war were borne disproportionately by working people. They feared that military conscription was only a prelude to industrial conscription, (conscripting women and foreign workers to work at lower wages as Australian men went off to war,) and indeed an employers' group in Victoria had begun to argue for industrial conscription in 1916. The trade unions feared that industrial conscription would break the power of the union movement forever. They also resented deeply the fact that while the Wages Boards had been suspended at the start of the war, effectively freezing wages, the government had made no attempt to control prices, despite promising to do so. The cost of living had risen by 28 per cent by 1917, while the value of the pound fell, compounding the impact on workers and the poor. There was deep resentment at what was seen as war profiteering and the 'famine prices' it created.

The 'No' campaign therefore drew on a complex mix of principled opposition to compulsion and deeply felt class antagonism. It was to prove a powerful combination.

A free debate?

At the start of the campaign Hughes seemed confident of victory. In fact most commentators assumed that the 'Yes' case would prevail. Hughes had promised a free debate and vote on conscription. But as the bitterness of the debate escalated, and more and more mass meetings and rallies were held, the Government became increasingly repressive. 'No' campaigners found municipal halls closed to them, forcing them into lesser halls or the open air. Government also made free use of its wartime powers of censorship, seizing literature it deemed subversive, censoring newspaper comment (although only the opposition press) and finally seizing some of the actual presses themselves. As the war progressed more regulations were added to the War Precautions Act 1915, until there were more than 100 of them. The Wobblies were subject to particularly close surveillance. Twelve of their members in Sydney were arrested during the campaign and charged with treason-felony for allegedly planning to burn down Sydney businesses. Later Hughes moved to criminalise the organization itself through the Unlawful Associations Act 1916. Such attempts to repress 'free speech' were deeply resented and were probably counter-productive.

The result

The result was a narrow victory for the 'No' campaign. Commentators were stunned. Hughes was devastated. Voter turn-out was the highest on record: 83 per cent of registered electors cast a vote. The 'No' vote secured 51.6% of overall votes : the 'Yes' vote 48.4%. A majority of voters voted 'No' in New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia and in the country as a whole. The 'Yes' vote prevailed in Victoria, Tasmania and Western Australia. In Victoria the count divided 51.9% in favour and 48.1% against, to the great disappointment of local anti-conscriptionists.

Of particular interest was the vote of the armed forces. Hughes had ordered that the forces be polled first, assuming that they would vote overwhelmingly in favour. He planned to release those figures in advance of the poll to encourage support for conscription. But he was disappointed. Although a majority did vote in favour, it was by a much smaller margin than Hughes had hoped (55%) and he withheld the figures until after the referendum date.

The political fallout

The aftermath of the 1916 referendum was as bitter as the campaign itself. The Labor caucus moved an immediate vote of no confidence in Hughes as leader. A defiant Hughes walked out of the party room taking a group of supporters with him, and formed a coalition government with his Liberal opponents. He was expelled from the Labor Party shortly afterwards and was ever after derided in the Labor press as a 'Labor rat' - or deserter.

The opinion of the Australian people was rather different however and reflected the contradictions embedded in attitudes to conscription itself. Hughes went on to lead his coalition Nationalist Party to an overwhelming victory at the following federal election held in May 1917. In the House of Representatives the coalition won 53 seats to Labor's 22. In the Senate they won all 18 vacancies. Hughes contested the election from a new seat in Bendigo, having lost pre-selection for his former seat of West Sydney. Despite many scandals in the lead-up to the election, including actions that have been labelled 'corrupt' by historians, the Australian people seem to have trusted Hughes to manage the country in wartime. Hughes remained Prime Minister until 1923. The outcome for the Australian Labor Party was far more serious. Apart from a brief period during the Great Depression, Labor did not regain office federally until 1941.