The anti-conscription cause was presented by a loose coalition of groups, including labour organisations, civil libertarians and anti-war groups. Its bedrock was the broad labour movement, expertly coordinated by John Curtin (later Labor Prime Minister), and expressed through the labour press. Newspapers like the Labor Call and the Australian Worker were especially strong and consistent supporters. The Australian Labor Party itself was divided, although a majority supported the 'No' case. Labor's support of the anti-cause was especially strong in Victoria, New South Wales, South Australia and Queensland, although some individual Labor leaders (apart from Hughes himself) were in favour.

Radical groups

These large organisations were joined by smaller, but well-organised radical groups, many of which also opposed the war itself. They included the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), also known as the Wobblies, a socialist group originating in America (Chicago) but established in Australia from 1907. The Wobblies were very organised and extremely committed, with strong networks and effective disruptive tactics. They also used both song and humour very effectively. Many of their meetings and demonstrations were accompanied by rousing songs like 'Solidarity Forever' and 'The Red Flag', which stirred emotions and bonded campaigners. The Wobblies inspired particular hatred in Billy Hughes who did his utmost to suppress the organisation.

The Women's Peace Army was another prominent radical group. It was founded by long-time feminist and pacifist Vida Goldstein and the feminist socialist Adela Pankhurst in 1915 and campaigned for peace throughout the war. Between them Goldstein and Pankhurst, with the assistance of other radical women like Jennie Baines and Lizzie Wallace, convened meetings and led well attended marches, attracting large crowds of supporters. Singing also featured in these meetings. One song in particular, 'I didn't raise my son to be a soldier', became so popular that the government banned it. Pankhurst and Baines were also active in demonstrations against price rises. These demonstrations led to actual food riots in 1917. Pankhurst was another thorn in Hughes' side. He called her a 'damned nuisance' and threatened to deport her. Both Pankhurst and Baines were gaoled for their activities.

The case for 'No' - defence of 'liberty' against 'militarism'

Anti-conscriptionists also argued in the name of 'liberty' - defending the right of ordinary men to decide for themselves whether to fight and die. They argued that conscription was the ultimate form of state tyranny. It would introduce the same kind of militarist oppression Australians were supposedly fighting against in France.

Equality of sacrifice

They also argued passionately for 'equality of sacrifice', believing that the cost of war weighed mostly heavily on workers and the poor. There was particular bitterness that governments had responded quickly to the outbreak of war by abolishing wages boards and effectively freezing wages, while prices soared with wartime inflation. Hughes himself had promised to introduce price control, but later reneged, to the anger of many labor supporters.

Propaganda for the 'No' campaign

The labour press was particularly effective in printing and circulating graphic posters, cartoons and leaflets, despite increasingly repressive government censorship. Brilliant cartoonists like Claude Marquet made effective use of well-established labour caricatures. 'Mr Fat', the rapacious capitalist, appeared in a new guise as the hated war profiteer, or the food exporter, stockpiling food to send overseas while people at home starved. His female equivalent was the equally fat 'Mrs Toorak', a wonderfully supercilious creature, dressed in furs and carrying a lap dog, generally shown looking down on her social inferiors. In the cartoon shown she stands over a poorly dressed mother nursing a baby, with the caption, 'Mrs Toorak: "What a blessing it's a boy. He can work and fight for us." ' Billy Hughes also featured in many anti cartoons, depicted as a small wizened gnome, scribbling the 'death ballot', or sneaking about as the Labor 'rat'.

Image courtesy National Library of Australia

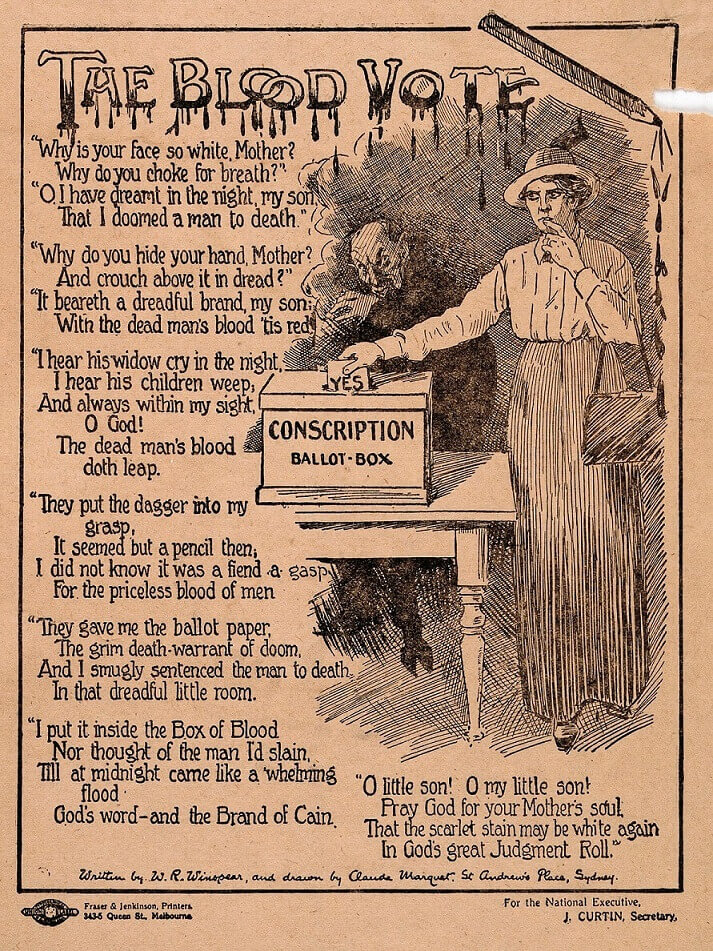

'The Blood Vote'

Perhaps the most famous poster of the conscription debate was the 'No' campaign's 'The Blood Vote', which was aimed at women voters. More than one million copies of this poster were printed after it was first published in the Australian Worker. The Worker ran it twice - the second time as a full-page cartoon on the day before the vote in October 1916. It showed a haunted-looking woman drawn by Claude Marquet in the act of voting 'Yes', prompted by a demonic Hughes in the background. Both the title and the voting pen dripped blood. It was accompanied by a poem which at the time was attributed to W.R. Winspear, but is now thought to have been written by the journalist E.J. Dempsey. Since Dempsey worked for a pro-conscriptionist newspaper, he may have preferred not to be associated with the work. The first verse ran:

'Why is your face so white, Mother?

Why do you choke for breath?'

'O I have dreamt in the night, my son:

That I doomed a man to death.'

'The Blood Vote' was so successful that it prompted the 'Yes' campaign to write a reply, but it was not as effective. Its verse was aimed at men, rather than women.

'Why is your face so white, brother?

Why are your feet so cold?

Are you afraid to fight, brother?

To guard that Mother, old?'

Image courtesy Australian War Memorial

Propaganda and the conscription debate | Read more

Further reading

Verity Burgmann Revolutionary Industrial Unionism: The Industrial Workers of the World in Australia Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1995

Phillip Deery & Julie Kimber (eds) Fighting Against War: Peace Activism in the Twentieth Century Melbourne, Leftbank Press, 2015

Stuart Macintyre & Geoffrey Bolton The Oxford History of Australia, Volume 4. The Succeeding Age, 1901-1942 Melbourne, Oxford University Press, 1993

Judith Smart, 'The Right to Speak and the Right to be Heard: The Popular Disruption of Conscriptionist Meetings in Melbourne, 1916', Australian Historical Studies, vol. 23, no. 92, pp. 203-19.