Manufacturing continued to expand in Victoria after the First World War and by 1921 secondary industry outstripped primary industry as the largest source of employment for the first time. Although hit hard by the Great Depression (1929-1933), when some 40,000 jobs were lost, Victorian industry rebounded and was well placed to expand its chemical, munitions and heavy engineering industries during World War II. Clothing and textile mills also repurposed during the war to supply uniforms, while food processing factories expanded to supply troops serving in the Pacific and to top up food supplies in the United Kingdom.

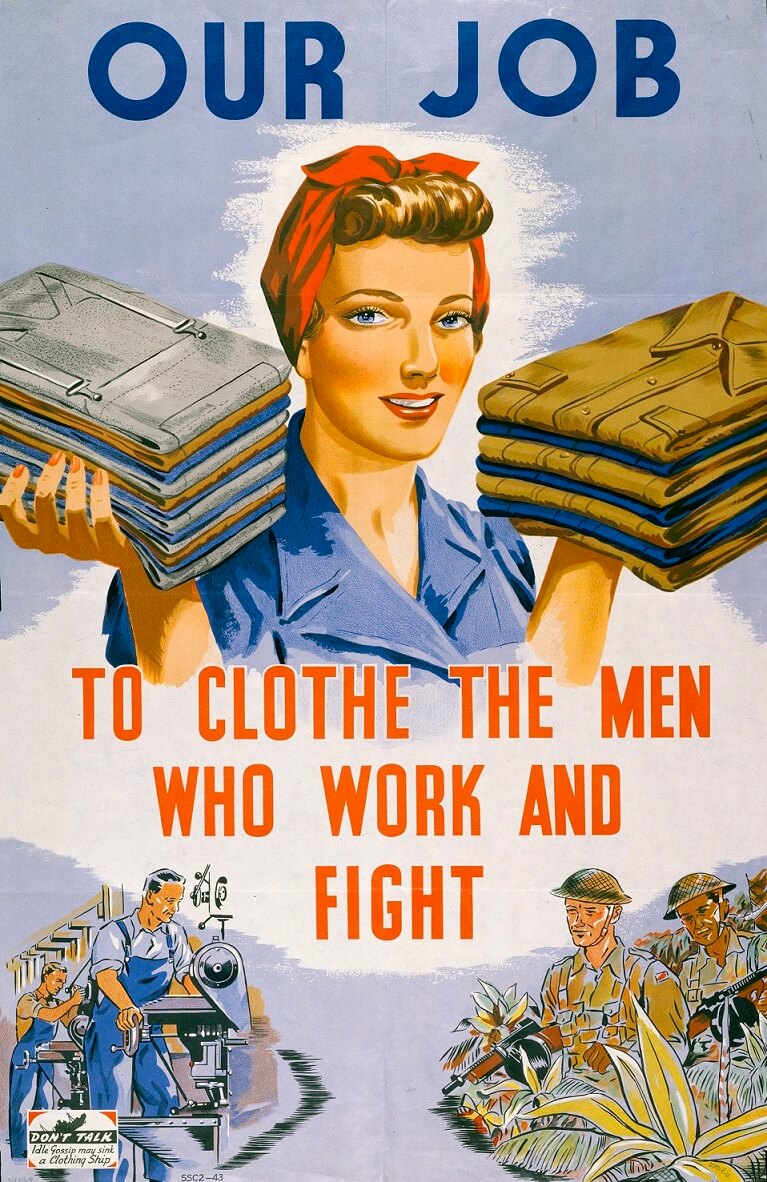

As more men were called up to serve, women were asked to fill the gaps left in the factories. For the first time, women workers were welcomed into heavy engineering works and in the munitions factories, which were male preserves before the war. Although their pay still lagged behind that of their male co-workers, this improved gradually. By the end of the war women working in jobs formerly classified as ‘men’s jobs’ were paid up to 90 per cent of the male rate, although the more common rate was 75 per cent. Unfortunately, those working in traditional women’s jobs in the food and textile industries did not share in this wartime bonus, and those factories began to find it more difficult to recruit workers as a result. A vigorous recruitment campaign began to entice women into the factories.

Recruitment poster for work in clothing factories, c. 1943.

Reproduced courtesy Australian War Memorial

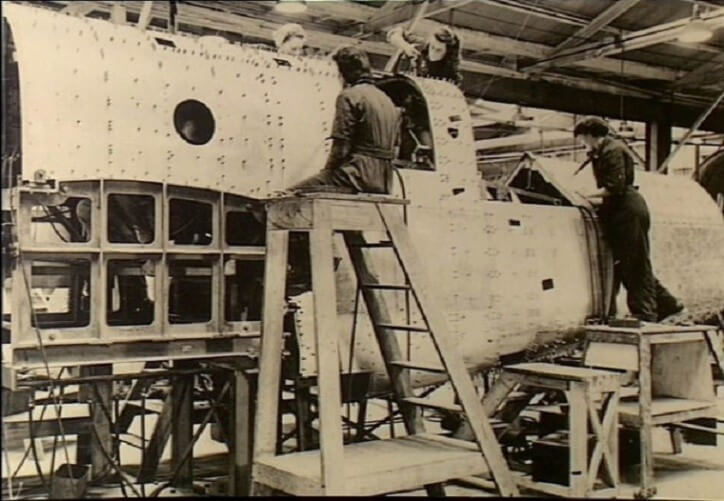

Propaganda photographs during the war recorded the achievements of women working in jobs formerly reserved for men, hoping to encourage others to join them. The general consensus in newspapers and magazines was that women workers did the job quite as well as men — much to the surprise of the commentators!

Women working at the Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation Factory at Fishermens Bend.

Reproduced courtesy Australian War Memorial

Conditions in the factories

Conditions in the factories came as a shock to some of these women, who had not worked in industry before the war. Elly Blackshaw was disgusted by the conditions she found in the local woollen mill. When Elly’s husband enlisted she found herself with time on her hands and found a job working the night shift in a local factory, but she soon left. As she later told researchers:

The smell of scoured wool was awful, the heat oppressive and there were no facilities for washing in the toilets. It was just a dirty job, so I left. (Goldsmith & Sandford, The Girls They Left Behind)

Despite working the night shift and half of each Saturday, her pay was only £2 per week — half the men’s wage. She applied instead to work at the Maribyrnong Explosive Factory. Work in the munitions factory was equally hot and also dangerous, but at least the pay was better. During the war women had options and they exercised them!

Even elementary health and safety precautions were often lacking. In 1936 one group of women toured a local Sunlight soap factory and were horrified by the working conditions they saw.

We were amazed to find that respirators are not provided for the girls working in the department where Rinso soap powders are wrapped. The air was thick with powder, and some of the girls had scanty handkerchiefs over their nose and mouth. What an effect this must have on the lungs of these girls! (Reported in Woman Today, August 1936)

These women decided that such jobs were definitely not for their daughters, but most women (or men) had little choice if they needed the work.