Madame Brussels (1851-1908) was one of the most famous brothel-keepers in late nineteenth-century Melbourne. Her houses in Lonsdale Street entertained men of influence and made her a wealthy woman. Her clients were said to include parliamentarians, wealthy businessmen and members of the legal profession, who were rumoured to have protected her from prosecution on many occasions. Madame Brussels was one businesswoman who managed to profit from the double sexual standards of Victorian Melbourne.

The ‘Social Evil’

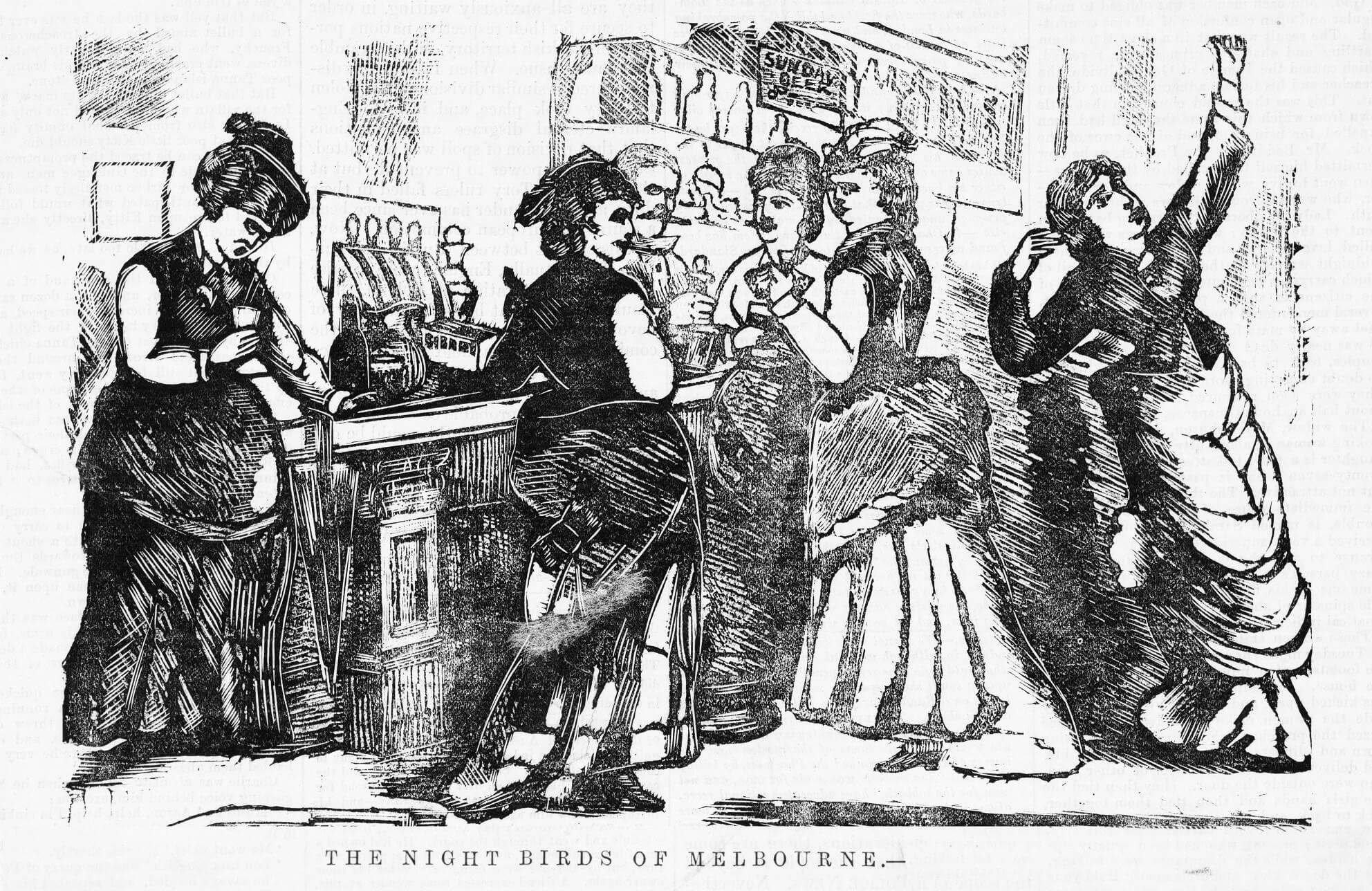

Late nineteenth-century attitudes to sex work were complex and contradictory. Officially sex work was frowned upon. Sex workers were described as women of ‘ill repute’ – ‘loose’ or ‘fallen women’ who led ‘depraved’ lives. Several of the women featured in this exhibition were so-described by the police in background reports preliminary to sentencing. Emma Williams was one whose association with the sex trade was another black mark against her. Reformers called prostitution the ‘Social Evil’ and tried to stamp it out.

But unofficially brothels were often tolerated as ‘necessary evils’, protecting ‘respectable’ women from men’s uncontrollable sexual urges. Soliciting was not made illegal until 1891 and running a brothel was not a crime until 1907. Before that brothel-keepers were mostly prosecuted for ‘keeping disorderly houses’, which tended to mean premises that were noisy, drunken and/or haunts of thieves. Women who conducted themselves ‘quietly’ often evaded prosecution. Street women were controlled through use of the vagrancy laws. Beatrice Phillips had repeated convictions for vagrancy, often a thinly-veiled reference to soliciting. But the association between brothels and other crime also meant that the police still preferred to confine such premises to certain precincts. The most famous was that around ‘Little Lon’ – the city block bounded by Spring, Little Lonsdale, Exhibition (initially Stephen) and Little Bourke streets. By the 1890s Madame Brussels owned several houses in this precinct, conveniently located just across the street from Parliament House.

Little Lon as a sex work precinct

Brothels were located in Little Lon from the early 1860s and by the 1890s they were very numerous. In 1898 the police knew of some 17 brothels in Lonsdale Street, and at least six operating in Exhibition Street, despite attempts to remove them from this grand boulevard at the time of the Centennial International Exhibition in 1888. The more salubrious establishments, known as ‘flash houses’, were located along the north side of Lonsdale Street near Spring Street, and of these the most exclusive were the premises managed by ‘Madame Brussels’. Less desirable houses were located in the side streets, alleys and laneways between Lonsdale and Little Bourke streets. Respectable Melburnians avoided these narrow streets after dark, when the meagre light of the flickering gas lamps barely penetrated the gloom. Only the larger streets boasted the new blazingly-bright electric street lights in the 1890s.

From Caroline Hodgson to ‘Madame Brussels’

Caroline Lohman was born in 1851 in Prussia, and married Studholme George Hodgson in London in February 1871. Hodgson was said to have come from a land-owning family, but immediately after their marriage the couple left for Melbourne to join Studholme’s brother John and his wife Lizzie Jane. Caroline and Lizzie Jane Hodgson became firm friends. The brothers went into business, but both ran into trouble in the recession of the 1870s. John eventually moved to Sydney, while Studholme joined the Victorian Police and was stationed in regional Victoria.

Perhaps life as a country policeman’s wife did not appeal, because Caroline remained in Melbourne running a boarding house. At some point she evidently realised that there were more profitable alternatives, and within the year she was running a brothel in North Melbourne. Within two years she had saved enough to buy a house in Lonsdale Street and by 1874 was running several brothels under the name ‘Madame Brussels’. How this was regarded by her policeman husband is not recorded. The Hodgsons do not appear to have lived together during this period, although they obviously remained friendly. When Studholme was diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1892 Caroline arranged for him to be nursed at ‘Gnarwin’, a property she owned in St Kilda. He died in 1893.

A ‘notorious woman’

By the 1880s Carline was a well-known identity in Melbourne. She lived at one of her establishments at 32-34 Lonsdale Street, described by historian Philip Bentley as ‘a high-class, extravagantly furnished bordello, operating as something of a libidinous gentleman’s club’. (ADB entry) Amongst her friends were prominent politicians David Gaunson, who also acted as her legal representative when required, and (Sir) Samuel Gillott, who was one of her mortgagors. Such ‘high connections’ probably helped her to escape prosecution on several occasions, much to the fury of moralists. But Caroline was also a highly skilled businesswoman, who ran her businesses profitably. She probably knew her way around the law extremely well.

However her very success attracted public attention and drew the ire of moral reformers. As movements for ‘social purity’ grew in strength from the 1880s, government was under increasing pressure to suppress prostitution and close the brothels. Baptist preacher and moral campaigner Henry Varley denounced the ‘degrading vices which were a scandal to the City and colony’ at a public meeting in the Theatre Royal in 1889, and denounced the fact that the ‘stronghold of hideous vice with which the name of Madame Brussels is connected has been tolerated and practically unattacked for nearly thirty years.’ [a great exaggeration] The Weekly Times reported his speech in detail:

Thirty years of consent to the buying and selling of young girls and women for the most degrading immorality, in which Government, magistrates, police, and people have either been silent, or the efforts put forth have been so feeble that the notorious woman has not only laughed at the authorities, but accumulated thousands of pounds in her accursed traffic in the bodies and souls of young girls.

Mr Varley was delighted that ‘Melbourne, the chief City of the southern hemisphere’, would soon see a revival of the Social Purity Society, which would lead a deputation to the Premier in the near future. (Weekly Times, 15 June 1889, p.7)

Campaigning for social purity

Mr Varley was supported in his crusade by other committed and able campaigners. Bessie Harrison Lee was another strong advocate for social purity and allied causes – temperance, raising the age of consent for girls and the suppression of prostitution. Writing in the Weekly Times in September 1893 she deplored the claim that one in 14 births in Victoria was illegitimate, while one in 22 single women were said to be ‘leading an immoral life’. ‘If this be anything even approaching the truth, it is awful’, she wrote, ‘a shame and a disgrace alike to the manhood and womanhood of our nation.’ (Weekly Times, 23 September 1893, p. 24)

Determined groups led deputations to the Premier, arguing for stronger regulation of ‘houses of ill-fame.’ One group met with the Chief Secretary in May 1893, but the Independent newspaper, published in Footscray, was sceptical of the outcome. ‘We must admit with regret the existence of evils in our midst, which are most lamentable, but at the same time the effort must surely be futile which attempts to “make people moral by act of Parliament” ‘, it commented. (24 May 1890, p. 2) Nevertheless the campaigns continued, placing Parliament under increasing pressure to act against the brothels.

‘These poor unfortunate wretches’

Meanwhile the trade continued more-or-less openly. The Geelong Advertiser, which rather enjoyed pointing to the seedier aspects of life in its sister city, reported on ‘The Social Evil’ in Melbourne in January 1903. It cited the well-known Magistrate Mr Panton (who appears in many of these stories, and often heard cases of neglected children), who had heard the case of a brothel-keeper, Julia Norton, on a charge of ‘being the occupier of a disorderly house’. Other occupants of the house were charged with vagrancy. Mrs Norton’s house in Little Lonsdale Street was said to be ‘about the lowest in the city’, but the police who had arrested her in response to ‘complaints’, told a somewhat different story. They agreed that it was probably ‘objectionable’ that the ‘females were in the habit of sitting on the pavement in coloured wrappers, and smoking cigarettes’, in close proximity to a school and a ‘church of England mission home’, although it is not clear which was considered more ‘objectionable’- the smoking or the wrappers. But they pointed out in Mrs Norton’s defence that she ‘had the reputation of being good and kind-hearted to the women who lived at her house, and they would rather stay with her than with anyone else.’ The defence lawyer, Mr Forlonge, (who would later defend Emma Williams) added: ‘these poor unfortunate wretches must live somewhere’ – a grudging defence at best! But Mr Panton agreed in part, observing that ‘the Bench did not wish to be harsh with the defendants, and he would suggest their removal to another locality’. Chris McConville has argued that from the late 1880s and accelerating during the 1890s, the police made concerted efforts to rid the city of prostitutes, which only meant that the trade relocated into the neighbouring suburbs of Fitzroy and Carlton.

Strengthened police powers

Caroline Hodgson survived initial attempts to tighten restrictions on brothels in the 1890s, no doubt assisted by her legal allies. In 1890 a new Police Offences Act made police powers clearer. Then in 1891 an amendment to the act imposed more severe penalties on procuring young women for prostitution. This was a more effective deterrent. Under the 1891 Act brothel-keepers could be sentenced to 10 years’ imprisonment if girls under the age of 13 were found in their brothels, with a two-year sentence for girls between 13 and 16. These were serious penalties, although not as serious as they might have been. The maximum penalty for carnal knowledge of a girl under 16 was 10 years’ imprisonment. In October 1892 Caroline Hodgson narrowly survived an attempt to prosecute her for employing fifteen-year-old Sarah Rogers in one of her houses. Sarah’s family had informed the police, in a vain attempt to ‘rescue her from a life of shame’. It transpired that Sarah had been working as a pupil teacher at the nearby Model School, but had been dismissed. She had then gone to the brothel, claiming to be nineteen. Publishing the details under the heading ‘A Sad Case of Depravity’, the Age lamented Sarah’s apparent lack of remorse:

The girl was not abashed by the proceeding, nor did she make any secret of the life she was leading. Her behaviour at the watchhouse was marked by an apparent disregard of her position. (8 October 1892, p.8)

The advance of social purity

The campaign against Melbourne’s brothel trade grew in strength in the early years of the new century, fuelled by sensationalist stories published in the Truth newspaper in particular. Madame Brussels was a particular target of Truth, although it found her disconcertingly charming. In one column in October 1903 it described her ironically as ‘a perfect little lady’.

The fair-haired, well-behaved, quiet little woman was really charming, and possessed an insinuating, subdued, placid beauty bordering on the Aesthetic. Above all, she was clean of speech and angelically demure. She had none of the loudness and vulgarity associated with the common, fleshly, boozing, boisterous woman who follows illicit pleasure as a profession. In short, Madame Brussells [sic] was a perfect little lady. (Truth, 31 October 1903)

Perhaps this was the secret of her success. But her business days were numbered. In March 1906 Caroline was charged with ‘keeping a disorderly house’ after a wealthy grazier complained to the police that he had been robbed in her house. Seven of her employees were charged with vagrancy, although the charges were later dismissed. The case was widely reported in both the Melbourne and regional press under headlines like ‘A Squatter’s Troubles’. (Horsham Times, 9 March 1906, p.3.)

Later in the same year Truth published a major exposé of Madame Brussels and her associates, including Sir Samuel Gillott, whose role as her mortgagor was exposed. In vain Gillott protested that although he had helped to finance Caroline Hodgson’s properties, he was not aware of the nature of her business. In the resulting scandal he was forced to resign. As a member of parliament he had played a leading role in developing legislation to outlaw gambling and had chaired public meetings on the suppression of vice. The inference of hypocrisy was clear. Rumours soon began circulating that Gillott was suffering from ‘ill health’ and he resigned formally in December. (Herald, 4 December 1906, p.6) Shortly afterwards he returned to England and Madame Brussels lost an influential friend.

The end of Melbourne’s ‘flash houses’

The final blow came in the following year. In 1907 a new Police Offences Act made it illegal to manage a brothel, rent a property for use as a brothel, or live off the earnings of prostitution. The police acted immediately. As the Age reported:

A month ago the police created consternation amongst keepers and frequenters of disorderly houses in Lonsdale-street and neighbouring thoroughfares by baling half a dozen proprietesses of the principal places before the City Court, where Mr Panton added to their confusion by sentencing one of their number, Caroline Hodgson (Madame Brussels) to three months’ imprisonment. This sentence was subsequently altered to a fine of £10 on appeal to a higher court. (Age, 17 May 1907, p.6)

Caroline was back in court in May, before the long-suffering Mr Panton. She was represented by Mr Dethridge, who advised the court that all of the inmates had left her Lonsdale house in the intervening weeks and that business had ceased. Nevertheless Mr Panton only agreed to give her fourteen days ‘to get rid of the house’. The inmates of all of the houses run by the other ‘proprietesses’ had also dispersed. It was the end of the ‘flash houses’ in Lonsdale Street.

Retirement

The career of Madame Brussels was over and Caroline officially retired. By this time she was already seriously ill. She died in the following year of diabetes and chronic pancreatitis, leaving an adopted daughter and loyal servants well provided for. Her estate at probate was valued at £4,828. Caroline Hodgson was buried beside her first husband in the St Kilda Cemetery.

Private life

For all her professional notoriety, Caroline Hodgson kept her private life discrete. Although she and her husband appear to have spent very little time together, she maintained a friendly relationship with him and cared for him in his final illness. In 1895, two years after Studholme’s death, Caroline married again, to Jacob Pohl, a man fifteen years her junior. The marriage was not a success and the couple divorced in 1906, after a long separation. In between there were rumours of a relationship with composer Alfred Plumpton, who possibly fathered the daughter she ‘adopted’, but no birth certificate has ever come to light. Plumpton died in 1902. Caroline maintained her adopted daughter in her St Kilda home, away from the brothels, and very little is known about their relationship.

Remembering Madame Brussels

Although the Social Purity Society hoped to rid the city of the ‘notorious’ Madame Brussels, Melburnians have since celebrated the image of bohemianism her history invoked. There is now a small lane named after her in the former Little Lon area and a bar that bears her name. Other urban myths have also flourished, including a persistent rumour associating Madame Brussels’ establishment with the famous (or infamous) disappearance of the Parliamentary mace.

The disappearance of the parliamentary mace

The mace is the symbol of the office of the Speaker of the Legislative Assembly. In 1891 it disappeared mysteriously and was never recovered. Sensational newspaper stories suggested that it was taken to the nearby brothels by drunken parliamentarians and used in ‘low travesties of parliamentary procedure’. Although Madame Brussels was not linked with this controversy at the time, mythology has since evolved associating her with it. Like many urban myths, this story is remarkably resilient.

Rediscovering Little Lon

Little remains of the former ‘flash houses’ that once dominated the streets of Little Lon. Many were demolished before the First World War to create building sites for factories. These in turn were demolished to allow the construction of the Commonwealth building in the 1990s. In the late 1980s major archaeological excavation of areas of Little Lon took place, with further work in 2003. Although the archaeological sites did not coincide with Madame Brussels’ establishments, recent analysis of the artefacts recovered from these digs has confirmed the long association of prostitution with the Little Lon area, with evidence suggesting that the industry was already established there as early as the 1860s.

Author: Margaret Anderson

Further reading

Raelene Frances Selling Sex: a hidden history of prostitution Sydney, University of NSW Press, 2007.

Chris McConville ’The location of Melbourne’s prostitutes, 1870-1920’, Australian Historical Studies, Vol. 19, No. 74, 1980, pp. 86-97.

Barbarra Minchinton ‘”Prostitutes” and “lodgers” in Little Lon: constructing a life of occupiers in nineteenth century Melbourne’, Australasian Historical Archaeology, Vol. 35, 2017, pp. 64-70

Tim Murray et al The Commonwealth Block, Melbourne: A Historical Archaeology Sydney University Press, 2019