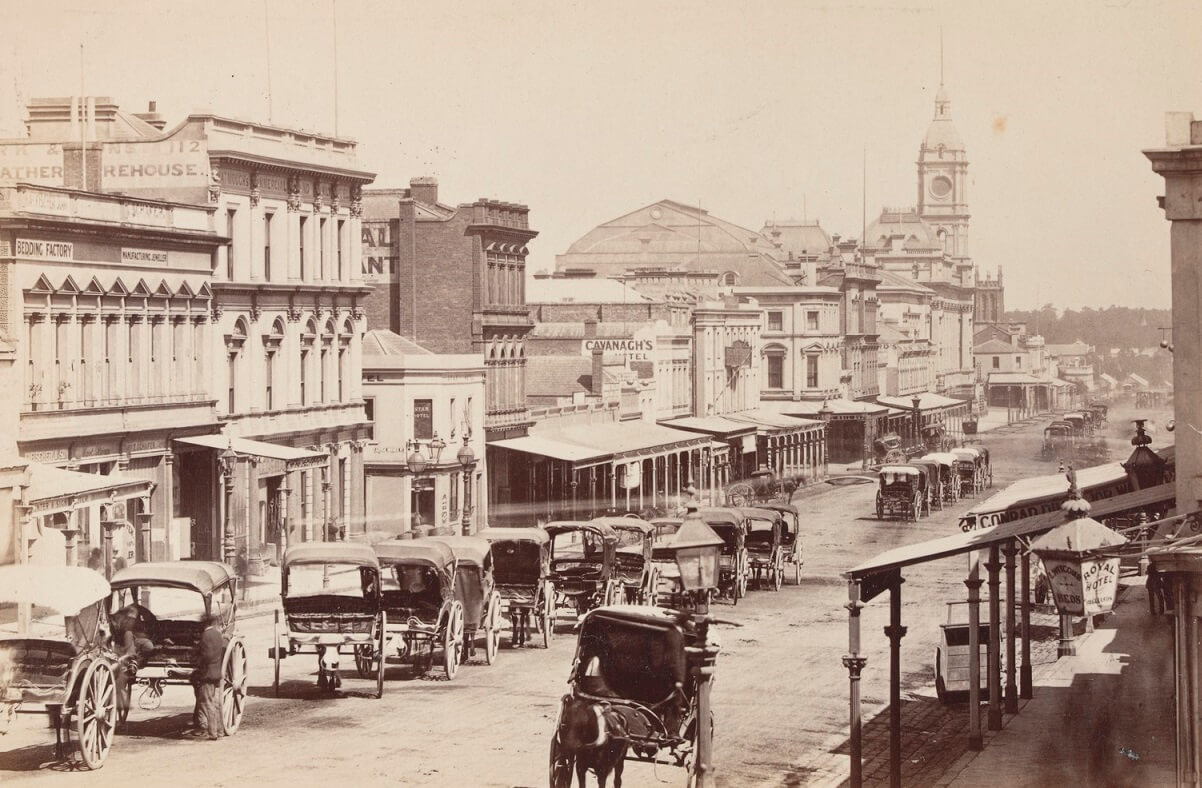

… we are standing at the corner of Bourke and Swanston streets, and having nothing better to do, we while away an hour by watching the Melbourne cabmen. From the position we have taken up, we can command a view of three stands, viz., the Sandridge, St. Kilda, and Collingwood, and we observe that while the main fleet, so to speak, remains at anchor, there are several smart piratical and privateering cabs, who evidently possess letters of marque, and back and tack, and fill and hover about on a kidnapping expedition. We see a stout elderly gentleman in a state of perspiration and nankeen, stop suddenly in front of Bignell’s Hotel; he pauses in order to brush an obtrusive mosquito from his rubicund nose. To do this it is necessary to raise his arm; this is enough – in a moment a half-dozen skirmishers charge vehemently upon him – a half-dozen wheels get irrevocably locked – a half-dozen cabmen swear a half-dozen violent oaths, and the stout gentleman is wedged in a labyrinth of vehicles and loses his presence of mind forthwith. He is emphatically ordered to “jump up,” and in sheer self defence does so, and is driven anywhere and charged anything.

Cab rank, with a line of Wagonettes, in Bourke Street near Swanston Street, by unknown photographer, c.1880

Reproduced courtesy State Library of Victoria

We have ascertained from unreliable authority (the cabmen themselves), that some 700 cars are plied in Melbourne, and as far as we can discover the average earnings of each driver is about 20s per day. The drivers for the most part are hired men, who receive a stated wage, and of course pay scrupulously every penny they earn into their employers’ hands. The cabman of Melbourne is, in real point of fact a nondescript; no two being alike either in personal appearance or individual character. We have no generation or families of cabmen in Melbourne as we have in London; the Melbourne jehu (coachman) for the most knew very little about horses or cabs before he landed in Victoria, and, consequently, despite the knowing air which he assumes, is very easily detected as an imposter. For the most part he affects an American style of driving, and shouts and yells at his horse in an obtrusive and energetic manner, holding his reins with two hands, without any earthly reason whatever.

We are essentially a riding public, a people on wheels, and we adopt to the full that wise axiom of that sensible Roman philosopher, Cassiodorus, “That the man who walks when he can ride is a fool.” Everybody rides in Melbourne, from the artisan to the capitalist (and could we go higher in the social scale), and everybody patronises cabs and cabmen.

Hansom Cab, built by Simmons & Sons, Coachbuilders, South Yarra, c.1880

Reproduced courtesy Museum Victoria

By 1850 regular cab ranks were established in Collins and Bourke Street. Initially cabmen would park close to the kerb and tout for passengers, but by 1858 they were required by council to take their stand in the centre of the road.

Though an undoubted public convenience, the cabs (and cabmen) were a mixed blessing. Some cabmen were rough and inexperienced, badly dressed and ‘smelt of stables’. Others were of dubious character. In 1867, The Argus newspaper labelled the bad cabmen ‘brigands, highwaymen and blackguards’. The following letter was published in the Mount Alexander Mail:

I ask any one to point out a more ill clad, dissipated, uncivil, lazy, sleepy lot of scamps than the cabmen… and why? Because they are under no control – either of police or otherwise, and when not asleep amuse themselves by quarrelling and making use of the most abominable language, and frequently leave their horses without any one to mind them for an hour. They also drive at a furious rate…

There was a range of horse-drawn cabs available for hire. Two-wheeled vehicles, known as ‘jingles’, were the first to appear on Melbourne’s roads. Carrying up to seven passengers, 'Jingles' were not particularly comfortable. Passengers sat over the axle and were bounced around on Melbourne's rough unmade roads. A small canopy provided only partial protection from the rain and sun, and the cabs were difficult to get on or off, especially for ladies in voluminous dresses.

Jingles remained in use until the late 1870s, replaced by the more comfortable ‘wagonettes’. Wagonette’s were four-wheeled vehicles, and passengers sat on benches in the back facing one another. There was an oil-cloth hood and side flaps that could be let down in wet weather. Like today's taxis, wagonettes could be picked up at cab ranks or booked to call at a home. Most suburban train stations had a cab rank, where a line of horses would await incoming trains.

The more affluent opted for a ‘hansom cab’. These had large rubber-tyred wheels for a smoother ride, and were decorated with stain-glass side windows, leather upholstery and carpet inside, sometimes even a vase of flowers. Some hansom cab drivers donned three-piece suits and bowler hats.

But long hours and meagre pay made a cabman’s life hard According to The Age newspaper:

… the cabs prowl through the city and suburbs from street corner to street corner, seeking whom they may drive, but much more often than one likes to think the hire of horse and cab is not taken. It costs on the average about 17s. a week for a cabman to keep his horse, and if he turns out in the early morning, as the industrious Jehu does, he must have two horses. Then there is the wear and tear to his cab and risk of accidents, so that if a man takes 10s a day – which he often does not – there is only the barest margin left for hours of very trying work. But the cabman who is his own proprietor is in an enviable position indeed, compared to his less favored brother who hires. The hiring charges for a hansom vary from 10s. to £1 5s. a day, and it must remain one of those inexplicable mysteries how the cabman under these circumstances can make anything at all out of his bargain. Yet he manages to exist week after week; but he only does so by working such long hours and under conditions that would cause an eight-hour advocate to shudder.

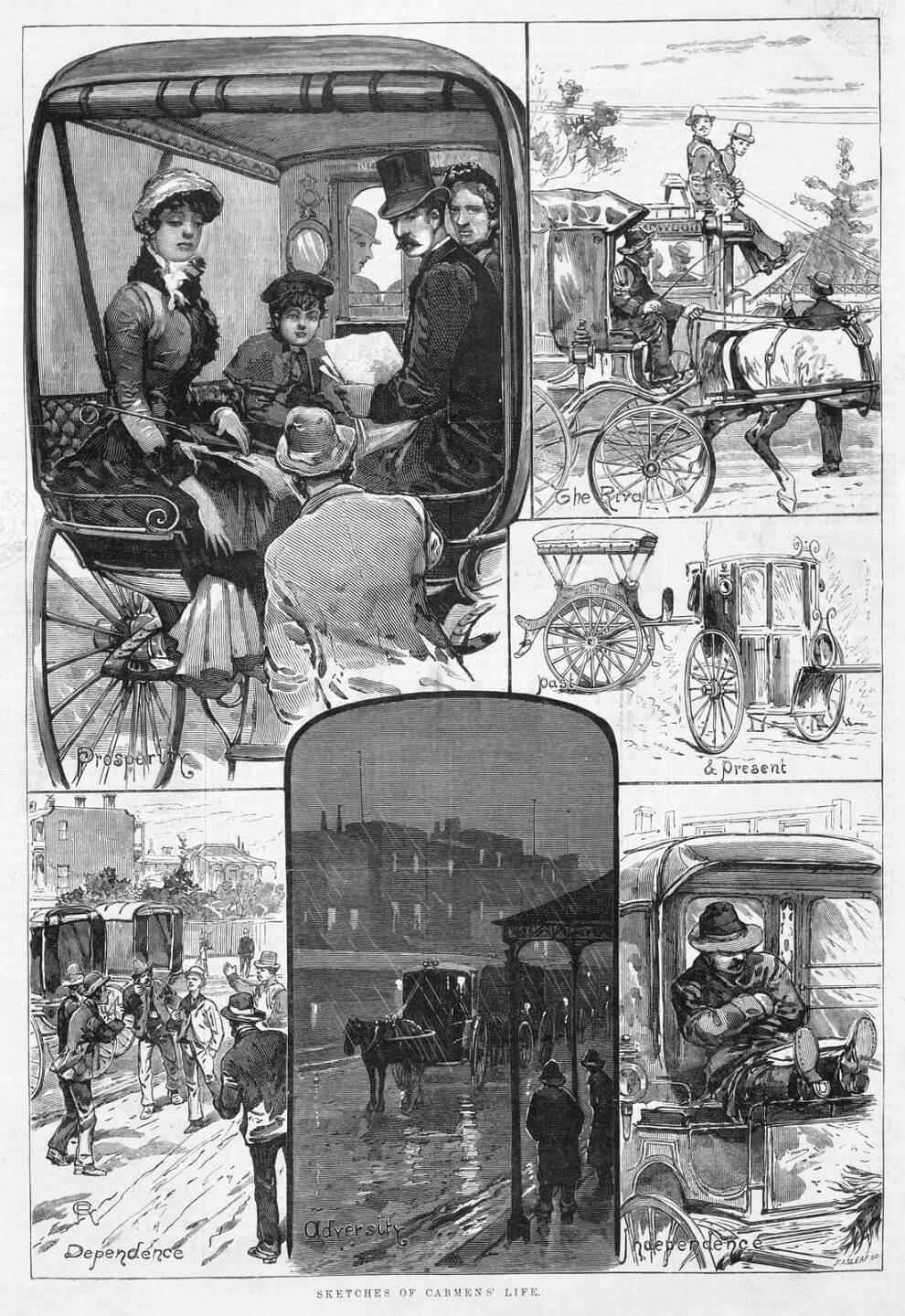

'Sketches of Cabmens' Life', by F.A. Sleap, artist, printed by David Syme and Co., 1885

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Cab rank in Swanston Street, by unknown photographer, c.1880. Note the cabs parked in the middle of the road.

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria