Shorthand and typing provided women with an entrée to the office, but it was a limited opportunity: even where (technically) eligible, they were not encouraged to apply for most general clerk positions, or for positions such as tellers in banks. The Commonwealth Public Service actually banned women from the administrative Third Division until 1947. On its passage in 1902 the Commonwealth Public Service Act also banned the employment of married women as permanent employees, the so-called ‘marriage bar’, that was not removed until 1966. Any married woman employed before the Act was passed was deemed to have ‘retired’!

Although the Victorian Public Service did not ban women from appointment as clerks, few applied successfully before labour shortages during the First World War necessitated their recruitment. Most of those appointments were temporary however, and there was no intention that women should be encouraged to seek a career in the public service. In 1917 a Royal Commission into the State Public Service made it clear that it thought women were ‘peculiarly fitted’ to work in a limited range of jobs, such as shorthand, typing and routine bookkeeping, and advised that they should be confined to appointment at a lower level, ‘thus leaving the path of promotion more open to the male members of the Service.’ (Victorian Parliamentary Papers, 1917, vol. 2, 107-8) Other institutions were even more opposed to the employment of women. Although some banks were also forced to accept female employees during the war, Charles Henderson, Melbourne Superintendent of the Australasian Bank, made his opposition to recruiting women quite plain in a letter to his General Manager in June 1915. Arguing that he preferred to appoint youths or older men to fill any gaps left by enlisted men, he wrote:

The employment of female labour is therefore unnecessary at present, and unless driven to it by absolute necessity, I strongly urge that the principle be not adopted.

I have always been a strong opponent of the employment of women in the Bank. …There are few posts in the Bank suitable for women except possibly for a few typists and one or two purely clerical positions in the largest offices….I should certainly strongly object to employing them as tellers, ledgerkeepers, exchange clerks or bill clerks. All these posts require a certain amount of training, besides secrecy and responsibility and I do not think women possess these qualifications. (ANZ Archives, 30 June 1915)

Similar arguments were repeated when women were asked to step in once again during the Second World War. Although many of these women enjoyed the work, which they generally performed with great efficiency, other aspects of their workplaces were not so congenial. One woman, identified only as ‘Elsie,’ found a clerical job in the public service working in the Treasury precinct. She had tried, unsuccessfully, for appointment before the war. Elsie was married, with a husband serving overseas. He was confirmed as a POW after the fall of Singapore. She very much enjoyed her work and felt that she performed her duties well, but there were other aspects of the workplace culture that she found offensive.

I’ll tell you what I didn’t like. Because you were married and your husband was away, men, it didn’t matter if they were young, old, married or single, seemed to think you were an easy mark. More so than with the single girls, just because you were married - not all men, but a lot of them. I just ignored it, but I used to feel really angry. (in Goldsmith & Sandford, The Girls They Left Behind, 196-8)

Elsie’s reminiscences are a reminder that women faced many challenges in the workforce in the past, including the very real menace of sexual harassment.

The secretary in popular culture

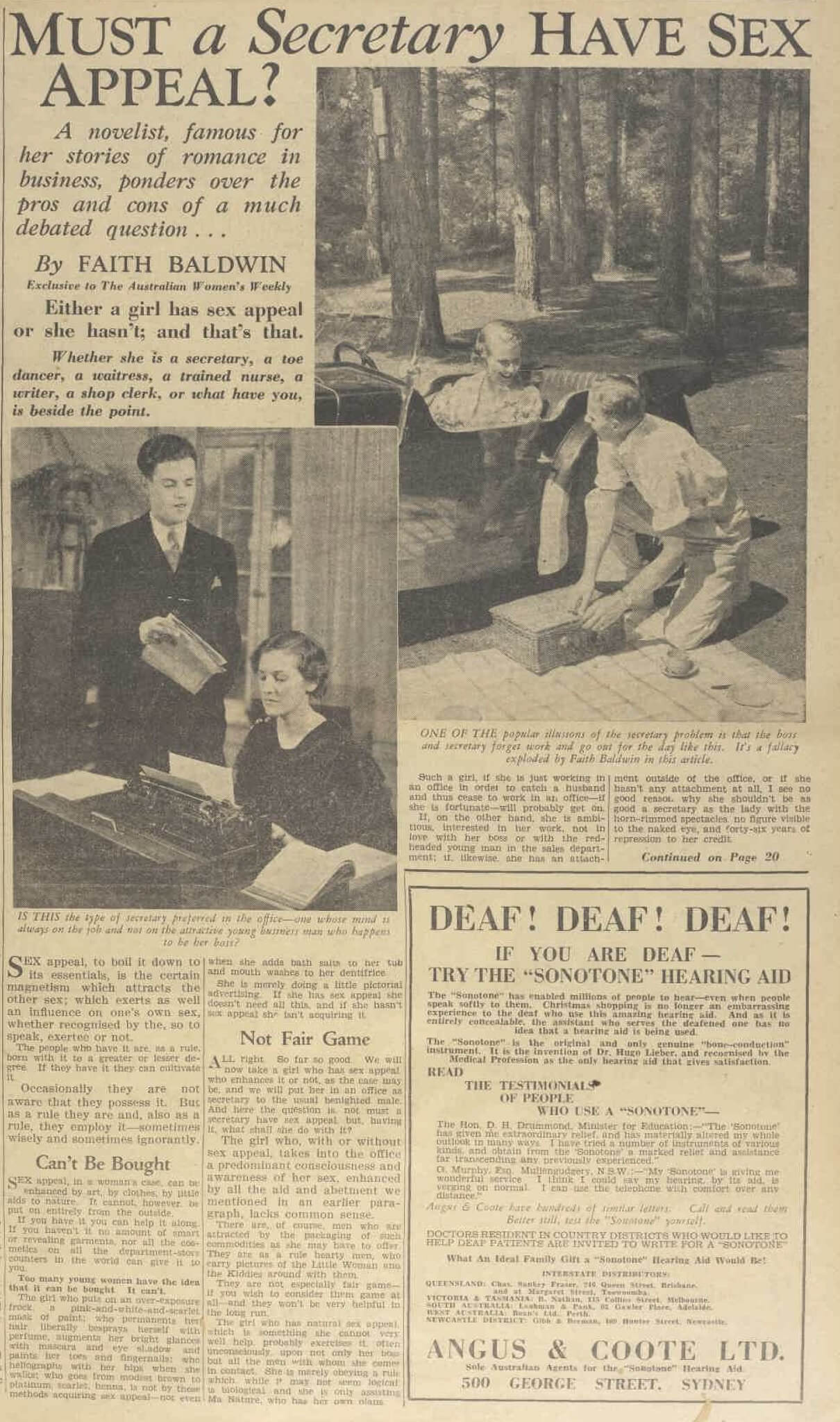

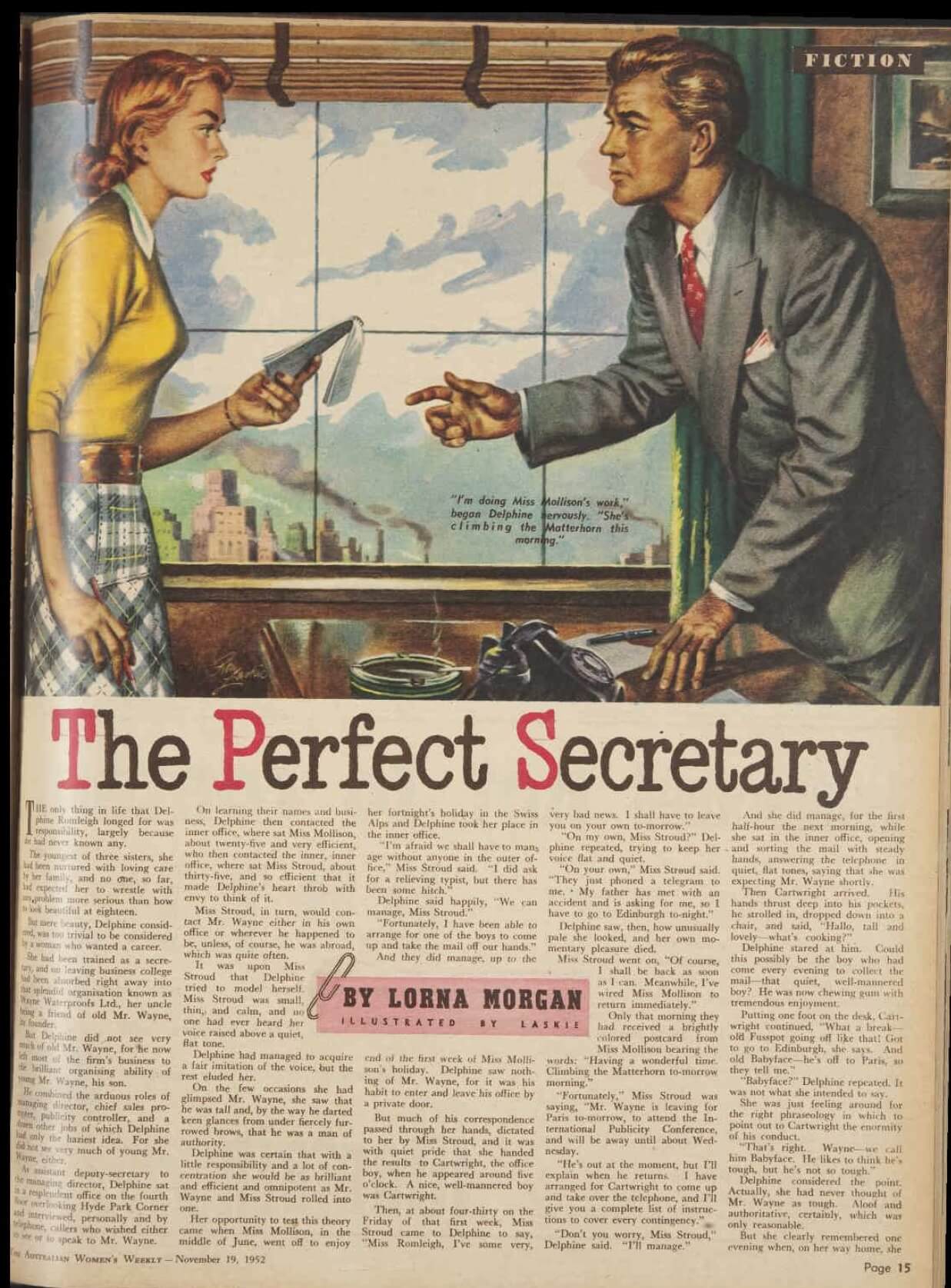

Very strong social pressures also directed women towards a limited range of white-collar jobs, which by the 1920s were strongly feminised and increasingly sexualised. All sorts of advice was offered to the ‘secretary’, from standards of personal grooming to advice on suitably deferential behaviour. There was a clear sense that the secretary should be as much an ornament to her office, as an efficient shorthand typist. Women’s magazines debated the essence of sex appeal, while one article in The Australian Women’s Weekly in 1936 asked the question directly: ‘Must a Secretary have Sex appeal?’ The secretary became a frequent heroine of romantic fiction published in women’s magazines and in the popular cheap novelettes produced by the successful publishers Mills and Boon, whose romantic fiction for women was produced from the 1930s. With minor variations, these romances followed a predictable sequence, in which the (pretty) young secretary fell hopelessly in love with her ruggedly-handsome boss, whom she invariably married in the end. The end game was inevitably not career, but matrimony.

‘Must a secretary have sex appeal?’, The Australian Women’s Weekly, 21 November 1936

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

‘The Perfect Secretary’, fictional story in The Australian Women’s Weekly, 19 November 1952.

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia