In late 1893 Frances Knorr was convicted of the murder of an infant in her care. She was sentenced to hang. The sentence followed a public outcry after the bodies of several infants were found buried in the back yards of houses she had rented. Two had been murdered. There was widespread outrage that many so-called ‘baby farmers’ continued to ply their trade, despite attempts at regulation. But official refusal to establish a foundling hospital meant that poor women had few alternatives.

Photograph of Frances Knorr, taken from her prison register, 1893

Public Record Office Victoria, VPRS 516/P0, Central Register of Female Prisoners, 5926-6415

Baby farming

In nineteenth-century Melbourne poor women who had to work had few childcare options. There were licensed nursing homes for babies, but they could only meet a small fraction of the demand. Unmarried women were especially badly off. Almost all jobs required women to work long hours and provided no childcare. Even live-in domestic positions were rarely prepared to accept a child. The alternative was ‘baby farming’, where women cared for other babies in their homes for a weekly, or sometimes a lump sum payment. In the latter case it is fairly clear that the tacit assumption was that the baby would not survive; that the mother was paying for her baby's quiet disposal.

In many — and probably the majority of — cases, baby farming was a legitimate occupation that merely formalised the informal child-care networks of single mothers and other labouring women. Boarding infants enabled some women to earn a living while remaining at home, making it possible for other women to go to work.

But the industry had its seamier side. Baby farmers were characterised, sometimes justly, as profit-seekers who neglected infants, or killed them outright. Many of the babies died in their care. There were rumours of neglect, insanitary conditions and slow starvation, while periodic exposés in the press contributed to public anxiety. The state attempted reform, requiring homes to be registered with deaths subject to inquest, but this was seldom enforced and many women, including Frances Knorr, evaded the regulations. Many deaths were probably not reported at all and, since the births might not have been registered either, there was no official record to show that these infants had ever existed.

Frances Knorr, popularly known as the ‘Brunswick baby farmer’, was convicted of murdering an infant in her charge and was executed in 1894. Knorr may not have been typical of the many baby farmers who were said to operate in Melbourne at this time, but her story probably gives some indication of the way in which this unsavoury trade operated and of the circumstances that prompted other women to make use of it.

Mrs. Grundy, an icon of Victorian respectability, throws a naked infant to a crocodile in this cartoon, Baby Farming – the real assassin, Bulletin, 1890

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

BABY FARMING EVILS.

Naturally the disclosures made during the hearing of the Brunswick baby farming and baby murder cases…, has somewhat focussed the ever floating question of the evils attendant upon our present defective laws for the preservation of child life, and the proper remedies for the existing state of affairs. For years the proposal to establish a Foundling Hospital has been before the public of Victoria, and it has been strenuously opposed. Now the situation is emphasised by the execution of Mrs Knorr, and many who previously were strongly against anything in the shape of an institution which might be said to offer an encouragement to immorality have seen reason to alter their opinions, and they now hold that of two evils it is certainly better to have the foundling hospital than that the fair fame of the country should be blackened by the ever-recurring baby murders, and the blot of such an execution as that carried out on Monday.

Ovens and Murray Advertiser, 20 January 1894, p.5

Frances Knorr, early life

Frances Lydia Alice (Minnie) Knorr was born on 6 November 1867 at Hoxton New Town, County of Middlesex, England. She was the second daughter (of seven children) of William Sutton Thwaites and his wife Frances.

Frances was from a respectable family in England. Her father was a tailor in Chelsea and she received a good education, including music lessons. However, in her teens she apparently fell in with a ‘fast’ crowd, and at 17 (some reports say 18) eloped with a soldier from the local barracks. He soon abandoned her, and she returned to her parents in a ‘very dirty and neglected state’. Her parents sent her to a reformatory school, but when this failed, they packed her off to Australia, ‘fearing the effects of her evil example on the younger children’.

Frances arrived in Sydney on the Abyssinia in 1887. Initially in domestic service, then a waitress, she seems to have gravitated immediately towards a group of petty criminals. In 1889 she married, or at least claims to have married, German-born waiter (and general lawbreaker) Rudolph (Rudi) Knorr. They were both convicted of theft on several occasions and both served terms of imprisonment in Sydney. There was one child of the marriage, a daughter Gladys, and possibly another child, born in Adelaide. They moved to Melbourne in about 1891.

According to evidence gathered by the police and reported in the press, the Knorrs were ‘carrying on the business of baby farming’. When Rudi was imprisoned in 1892, it seems that Frances continued the business with another partner, a fish-monger’s assistant named Edward Thompson.

Gruesome discoveries

In September 1893 the body of an infant was discovered in the backyard of a house formerly rented by Knorr in Moreland Road, Brunswick. Police immediately investigated another property Knorr had rented in Davis Street, Brunswick, and found the bodies of two more infants.

No obvious cause of death could be identified for the child buried at the Moreland Road property. Of the Davis Street bodies, however, both revealed evidence of foul play. According to reports, the second child had likely suffocated. Of the third infant, known only as No. 3, it was ‘found that a piece of tape was tightly drawn around the neck of the infant in such a manner as must have produced death in three minutes.’ The two infants were never identified; their mothers never came forward.

The case against Knorr

Knorr was arrested and charged with the murder of the infant discovered in Moreland Road. The child was later identified as Gladys Crighton, who was just a few weeks old when she died.

The prosecution painted a poor picture. Testimony showed that Knorr was firmly entrenched in the baby ‘trade’, a ‘broker of babies’ as such. She was the intermediary between the parent and the actual carer - more often a poor, needy woman. Knorr made a profit, pocketing the difference between the parent’s deposit and what was paid to the minder.

The prosecution claimed that Knorr got rid of the infants as soon as she could; and if she could not get rid of them quickly, she was ready to murder them:

What she did was hire out babies, in some instances to pay for them for a time, and then cease to pay, and in other instances to take them back, while in some cases it is not known what became of them… If she could not pay to get rid of the child she had a strong temptation upon her… to get rid of the children by some other means’.

Witnesses were called to comment on Knorr’s ‘dealings with babies’. (Frances Knorr was also known as France Thwaites — her maiden name. The following agreement was presented in court:

This is to certify that I, Mary Lynch, agree to give Lily Lynch to Frances T. Thwaites, to take as her own and adopt her as her own child, without premium. The sum of £5 is for outfit.

MARY LYNCH

I hereby promise that I will not trouble Mary Lynch any more financially.

Receiving £5 sterling, as above.

FRANCES THWAITES.

RUDOLPH THWAITES.

Mary Lynch testified that, ‘having some doubts about the prisoner’, she got her child back.

‘Two girls’ appeared in court and testified that they had seen a baby boy in the Davis Street property. They went out, and on their return, the baby was gone. Another woman, Lizzie Scholfelder, stated that in June 1893 she gave Knorr her sister’s child, together with a sum of £15, and she had not seen the child since.

Evidence presented at her trial suggested that Knorr approached the disposal of the infant Gladys quite systematically. It was revealed that Knorr had moved into the house on the Monday and that the child appeared to be in perfectly good health the day before its death, that it was buried on the Tuesday night or Wednesday morning, and that Knorr vacated the house the following Saturday. A man who lived next door to the house in Moreland Road gave evidence that Knorr had sent a child to him asking to borrow a spade, ostensibly to dig a garden, but returned it saying the ground was too hard.

But the evidence against Knorr was far from conclusive. No cause of death was ever established for the child found in Moreland Road and Knorr was not charged with the murder of the other two infants, although the Judge did admit as evidence the information that they had died of suffocation in one instance and strangulation in the other.

During the trial Knorr herself insisted that Gladys had died of convulsions and that she had buried the body in the garden because she ‘got frightened’. She testified in court:

I slept very well until about 2 o'clock when they woke up for a drink. I had a foot warmer [for heating milk] and when I got up and got the bottles rinsed out I found the milk was turned completely thick, quite sour, and it was impossible to give it to either of the children. I had no barley in the house and could not make barley water. I tried a little bread beaten up in hot water to make a sop. The two children continued screaming until morning and about a quarter to four the child Crichton died. It went black in the face and was working all over. I got vinegar and applied it to the head and put it on the lips but it never came to. It died from convulsions and not from any ill treatment on my part. I swear that 1 did everything in my power to resuscitate it .... 1thought of going to the police first but got frightened. Then 1 thought "I will bury it" .

Knorr charged Thompson with strangling infant No. 3, found in Davis Street, although she admitted to burying it in the garden. When she dug the hole, she found the body of the other child buried there. Knorr was, however, thoroughly discredited as a witness. She had foolishly written to Thompson from prison, asking him to fabricate evidence on her behalf. He immediately turned the letter over to the police, possibly in exchange for evading prosecution, although that is pure speculation.

The prosecution maintained that Knorr was deceitful and a ruthless racketeer. Her letter to Thompson was characterised as an audacious attempt, fortunately frustrated, to get the witness to come to court to swear falsely — ‘a scheme of villainy from beginning to end’. As to Knorr’s accusation against Thompson, the Crown asked what motive Thomson had to murder the child, seeing that he was under no obligation with regard to it. Knorr’s claim that Gladys had died of natural causes was also rebutted. If the child had died of convulsions, as Knorr upheld, why did she not alert the police, or at any rate the neighbours, who could verify her story: ‘If it died from convulsions, it was to her own interest to have the fact known as promptly as possible.’ Burying the baby was, they concluded, merely evidence of foul play.

District Coroner, Mr Candler, summed up. He said that it ‘appeared strange’ that Knorr should dig a garden in a house which she intended to leave. He surmised that the findings of other bodies in a house which she afterwards lived might be a coincidence, but it was certainly suspicious.

Court of public opinion

We would now conclude that there was little prospect of Knorr receiving a ‘fair’ trial. Public opinion ran high against her and there was widespread revulsion as the details of the trade in babies was revealed. During the trial Knorr was described in newspapers as the ‘baby killer’, ‘baby slayer’, or a female ‘Herod’. Some howled for blood. One journalist claimed the lash was ‘too lenient’ for Knorr, who could be ‘likened to nothing else but the priestesses of a modern Molooh [sic].’

The sentence

After only 40 minutes, the jury returned their verdict. Knorr was found guilty of wilful murder and was sentenced to hang. ‘Somewhat of a scene’ followed the verdict:

The prisoner was removed from the dock. She sobbed and cried, and had to be supported by a female warder and a police officer. As she descended the steps from the dock, she turned to the gallery where Thompson was sitting and exclaimed, “God help your sins, Ted”, and still sobbing and crying her last words as she disappeared through the doorway were “God help my poor mother”, and “God help my poor baby”. The scene was a most painful one.

At this time the sentence for murder was execution, although it was possible to petition the Governor for mercy. This was done successfully in other cases — like that of Maggie Heffernan. But Knorr was not a sympathetic character. The more lenient moral and criminal judgements attached to ‘pitiful and destitute’ women charged with killing newborns were not easily transferable to Knorr: she was the ‘wicked’ baby farmer who had no biological relationship to the infants in her care, but appeared to be making money out of the misery of others. Like Emma Williams she was said to be a woman of ’loose habits, immoral character and hardened nature’. Her crimes seemed especially repellent in the climate of anxiety around baby farming.

There was a general reluctance to hang women, yet many came out in full support of the sentence. The following article appeared in the Ballarat Star, 30 December 1893:

Frances Knorr is to be hanged for child murder — a horrible trade to which she had systematically devoted her energies. If capital punishment is to remain a part of the law of the land and infant life is to have any protection, such criminals as this woman must not be allowed to escape. It is impossible to avoid feeling pity and sympathy for a helpless unmarried mother, deserted by the father of her child, burdened with its support, and cut off from her past by the fact of its presence, if she forgets the sacred duties of maternity and attacks the life for which, had her natural instincts been allowed fair play, she would have given her own. But what sympathy can there be for the wretch who preys on such wretchedness as this, for the murderous harpy who, for the sake of a mere trifle of gain, wrings from the miserable mother whatever money can be scraped together, and then slaughters the hapless little being she has undertaken to protect. Our civilisation does not seem to have implanted in the hearts of men the slightest feeling of responsibility for those of their offspring who have no legal claim upon their care. Our legislation appears to break down under the problem of devising a means for dividing in any proper degree the burden of supporting such children between their parents. It may never acquire the necessary strength for such a duty, but at least it can step in and protect those already unfortunate lives from murderous assault. If Parliament were competent to legislate upon a question of such vital importance, the existence of such women as Frances Knorr would be impossible. As it is, the Legislature being confessedly impotent, the only thing that can be done is to sustain the executive when it has to stamp them out and put a stop to their bloodthirsty practices.

There were very few letters written in support of Knorr’s character. There were, however, a number of petitions calling to commute the sentence, arguing that Knorr’s crime was motivated by poverty. The following petition was sent by ten women to the Attorney-General and was summarised in the Herald, 13 January 1894. It began

with a protest against the “abominable, fiendish injustice done by so-called men whose lives are a reproach.” The petition then goes on to allege that the evidence against the prisoner was circumstantial; that the crime was probably die to poverty caused by the struggle for existence. Allusion is made to the fact that men have almost the entire management of the law, and that the acts of men of recent years have produced starvation and other manifold evils. It is argued that justice would be done if the woman were confined for a time and then set free.

A deputation consisting of the Reverend Charles Strong, the Reverend A.R. Edgar, Mr. John Hancock and ‘some ladies’ urged the reprieve of Mrs Knorr:

The deputation was the outcome of a public meeting held on a piece of vacant land in Russell street, and was accompanied by a crowd of a few hundred as far as the gates of Government House. Dr Strong said the deputation desired the Governor if possible to extend the prerogative of mercy to Mrs. Knorr. It was thought that the ends of justice would be served by her imprisonment for life. The Rev. Mr. Edgar said the growing sentiment of the people was in favor [sic] of the extension of mercy to prisoners.

Perhaps the strongest protest against Knorr’s sentence was made by the hangman, William Perrins. The night before Knorr’s execution was scheduled ‘Jones the Hangman’ committed suicide by cutting his own throat. It was said that he was overwhelmed because of his

unwillingness to execute Mrs Knorr, the baby farmer… shrinking from the contemptuous jeers and the persecutions of his neighbours, who, he believed, would be still more hostile if he hanged a woman.

The execution

Despite all this Frances Knorr was hanged on 15 January 1894. It is important to note that on the eve of her execution she confessed to killing two of the babies discovered. In a letter, Knorr claimed

As I feel that I have not expressed myself clearly, I now desire to state that upon the two charges known in evidence as No 1. and 2 babies I confess to be guilty. Placed as I am now, within a few hours of my death, I express a strong desire that this statement be made public, with the hope that my fate will not only be a warning for others, but also act as a deterrent to those who are perhaps carrying on the same practice.

Her last moment in gaol were reported. Editorials like this revelled in the drama:

It needed but a glance to show that the woman had determined to meet death with fortitude. With a firm step she crossed the narrow space between her cell and the railed enclosure, and stood on the fatal trap. Her face was pale, but her head was firmly erect, and there shot from her eyes a look that did not display the most remote evidence of fear. Her hair was neatly rolled up on the top of her head, and surmounted with the hideous white cap, whilst she was clad in a plain wincey dress made specially for the occasion. There was a running string round the bottom of the skirt, which was pulled tight, fastened in front, and leaded.

Her arms were pinioned behind her back, and whilst the hangman adjusted the fatal noose around her neck she leant slightly against the beam, whilst Dr. Shields and the Rev, Mr. Scott stood at her back, the doctor tapping her reassuringly and the chaplain urging her to bear up.

“Have you anything to say?” asked sheriff, Mr. Ellis.

“Yes”, was the woman’s reply, in a voice unbroken by tremor or emotion, “I do not care what man can do for me. I have peace – perfect peace”.

The sheriff signalled… and the last scene in the life of Frances Knorr had been grimly played. For a moment the woman hung suspended in the sight of all. There was no convulsive twitching of the legs – no movement to indicate that death had not been instantaneous, and the curtain falling hid for ever from the shocked spectators the body of the Brunswick baby-slayer.

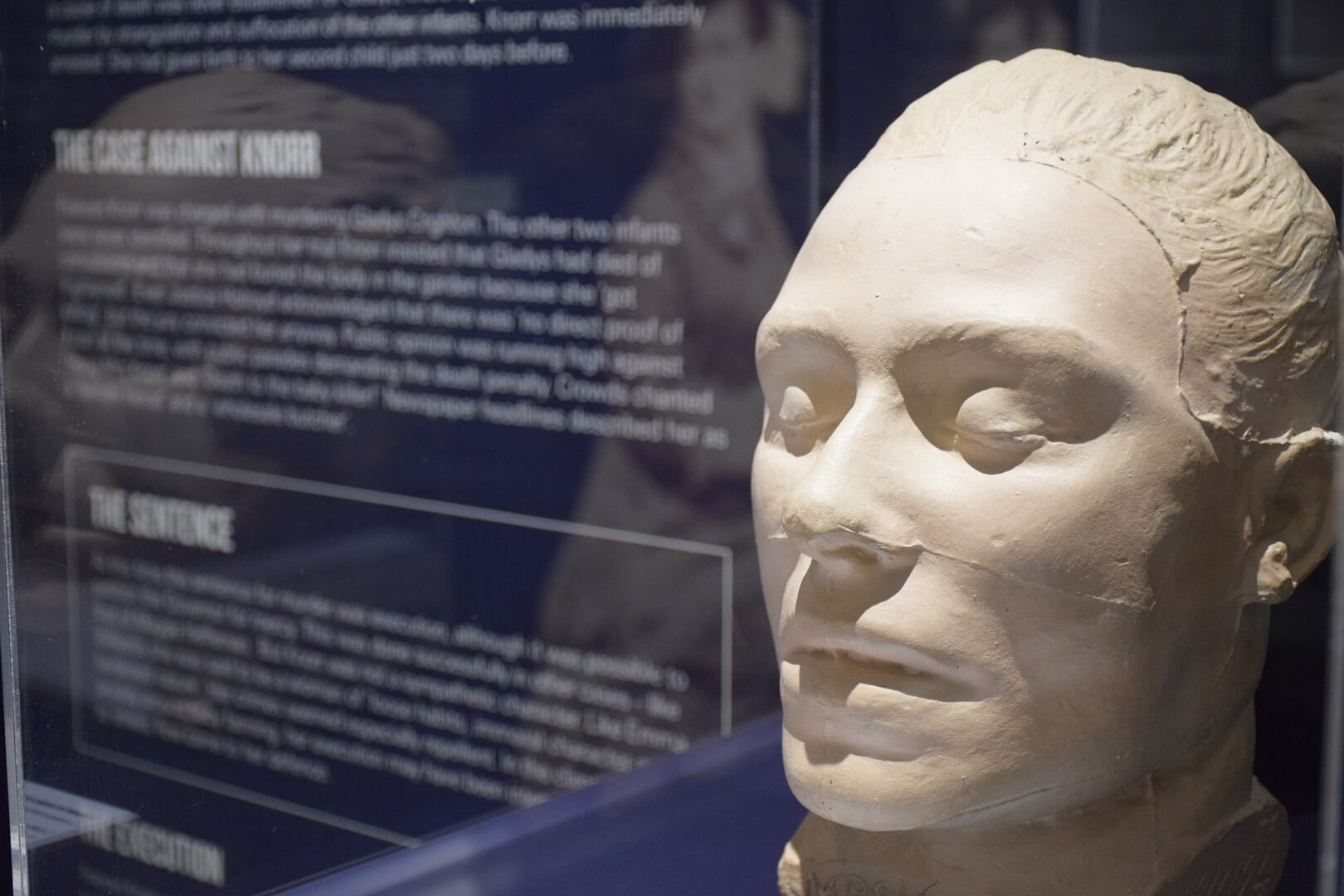

Death mask of Frances Lydia Alice Knorr, 1894

Courtesy National Trust of Australia (Vic)

Death masks were common in Australia from the early 1800s. They were mostly made from criminals and were used for exhibition purposes and for phrenological analysis. Phrenologists believed that the structure and morphology of the skull revealed certain characteristics – notably the existence of a ‘criminal type’.

The aftermath

The trial of Frances Knorr certainly focussed public opinion on an aspect of life in Melbourne that many found shocking, and it helped to stiffen the resolve of government to enforce the new regulations requiring all homes providing infant care to be inspected. But it is unlikely that the overburdened police force was able to suppress the trade entirely. There were simply too many informal arrangements in place. Government also remained trenchantly opposed to funding the creation of a foundling hospital (as advocated by Miss Sullivan amongst others) or adopting the supervised boarding out system followed in South Australia. Moralists insisted that such safety nets only encouraged immorality. And so the trade in human misery almost certainly continued. In January 1894 the Argus sought Miss Sutherland’s views on the need for state assistance. Miss Sutherland was a prominent advocate for single women and their children. She was highly respected and was often approached by the police or the courts to admit girls arrested on the streets to the home she ran in the city. Her response was unequivocal:

The present system leads to murder and to degradation; and the evil that is being wrought is increasing rapidly. If infant life is considered worth saving and the degradation of women and the crime of murder are not desired by the people, then steps should at once be taken to establish a foundling hospital.

Sadly, her pleas fell on deaf ears.

Postscript: What happened to Knorr’s children?

Knorr eldest child, Gladys, saw her mother two days before the execution. The January 20 Weekly Times described the scene: “[T]he sight of the mother clinging to the baby was particularly painful. . . . She heaped kisses on the poor little mite, and prayed that she “should never know” her mother was hanged. We presume Gladys was then cared for by her father Rudolph.

As for Frances’ youngest child (both Rudolph and Ted Thompson denied paternity), the following paragraph appeared in the Argus newspaper, eleven days before Knorr was hanged:

The Case of Mrs Knorr

The Infant Before the City Court

The infant Reita Daisy Knorr, which had been frequently before the City Police Court as a neglected child, was formally handed over to the custody of the department for neglected children. The child was born shortly before Mrs. Knorr was arrested on the charge of child murder (for which she is now under sentence of death)… The child has been in the custody of the police. An order was made by the Bench at the City Police Court for its commitment to the department for neglected children.

References

Trove, National Library of Australia

Public Record Office Victoria

Lucy Sussex, ‘Portrait of a Murderer in Mixed Media: cultural attitudes, infanticide and the representation of Frances Knorr, in The Australian Feminist Law Journal, 1994, volume 4