Many small industrial concerns grew up in regional Victoria in the wake of the gold rush. Flour mills, breweries, boot and shoemakers, soap and candle makers, bakeries and dairies all processed local products and supplied local markets. Some products, like butter and cheese, spoiled quickly and before refrigeration could not be transported over long distances. Beer was another product that did not always travel well, encouraging local producers who served surrounding areas. At first these products were all made by hand. Cows were milked by hand (at the rate of about four cows per hour), then the milk was allowed to sit to settle out the cream, which was then hand churned and salted for butter. The process was highly weather dependent, as both milk and cream spoiled quickly in hot weather, especially as the milk itself was unsterilized. It was estimated that milk could not be transported more than about six miles over flat country in safety, or less in hilly areas. This kept milk and cream processing local.

Refrigeration was a game changer. The first commercial ice-making machine was actually patented by a Scottish Victorian, James Harrison, whose business was located on the Barwon River in Geelong. His first machine was patented in 1851 and by 1854 he had built his first commercial ice-making machine. As the technology behind commercial refrigeration improved, the Victorian Railways began to build cool rooms at stations in dairying districts and developed a government cool store in Melbourne. By the 1880s ships fitted with refrigeration were able to export meat successfully from Australia to the UK but refrigerated road transport was still decades away.

The invention of a successful cream separator further improved processes for butter making. However this new machinery was expensive and increasingly butter and cheese making was centralized in larger factories. Government subsidies for exported butter from 1888 encouraged investment and local butter factories became important sources of employment in dairying districts. By 1895 there were 174 butter factories in Victoria and 300 creameries, estimated to produce an average of about 100 tons of butter per year.

Mirboo North Butter Factory, George Sutton photographer, 1910-13

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Butter factory, Alexandra, Lindsay Cumming photographer, c.1910-15

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Cooperatives

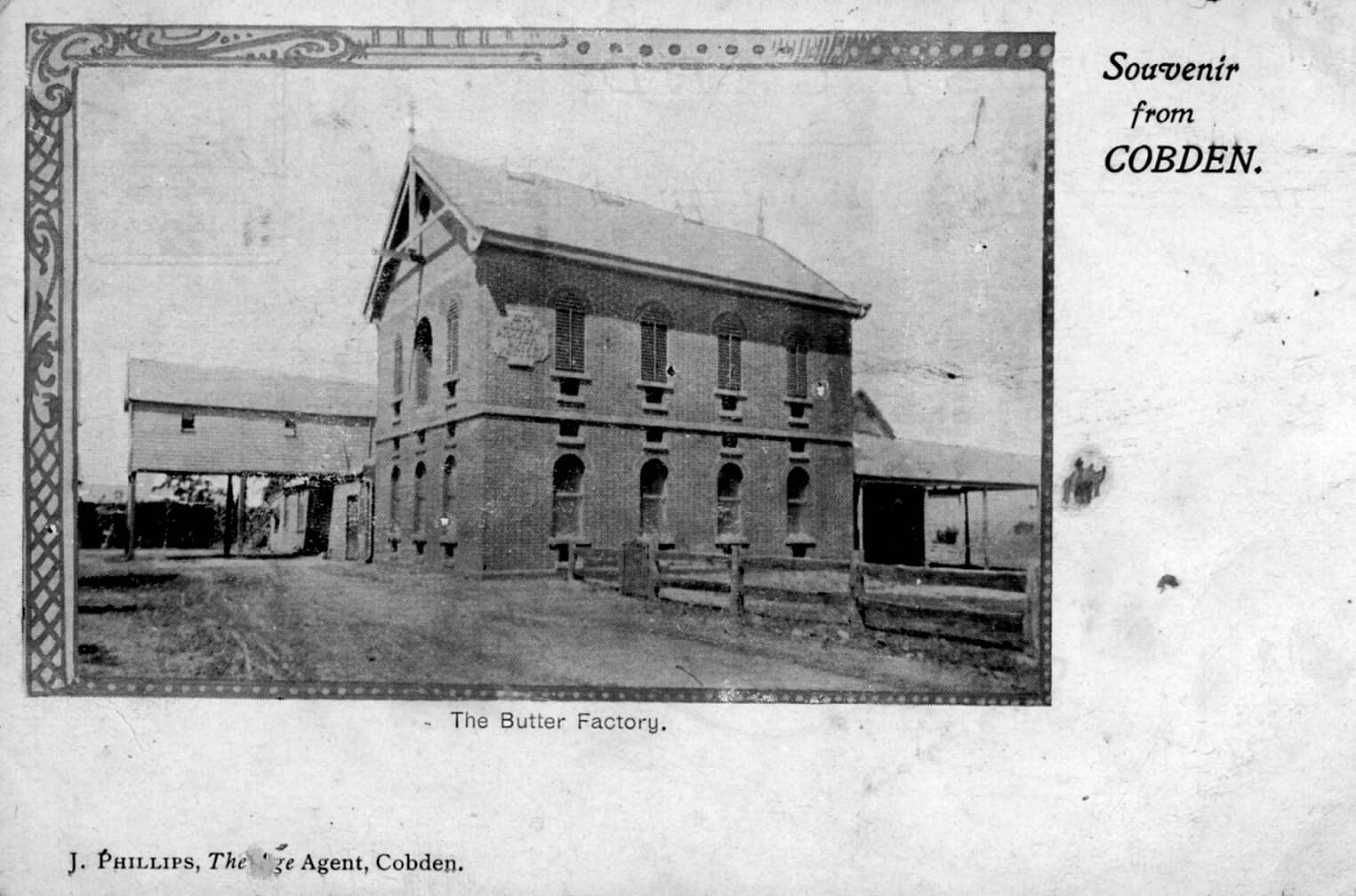

From the 1880s some butter factories and creameries developed as cooperatives, with staff acting as owner/managers. The first was established in Cobden in 1888 and by 1890 there were 32 cooperative factories in business.

Souvenir from Cobden, ‘The Butter Factory’, postcard c. 1912

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Mechanisation and consolidation

Despite the introduction of refrigeration and other improvements in butter making, in 1891 the bulk of butter was still produced on farm dairies. In that year some 15 million pounds of butter was produced in Victoria, two thirds of it on farms. But in the next few years this changed significantly. Overall butter production increased to 40 million pounds in 1894, by which time two-thirds was produced in factories. Exports also grew, from less than 2 million pounds in 1890 to 23 million pounds in 1894. It was a remarkable period of expansion. These factories were often housed in impressive buildings and they were important local employers. There was less change on the farms themselves. Although some of the larger farms could afford to introduce milking machines, most still milked by hand using family labour, which meant that individual herds were small.

Fruit processing

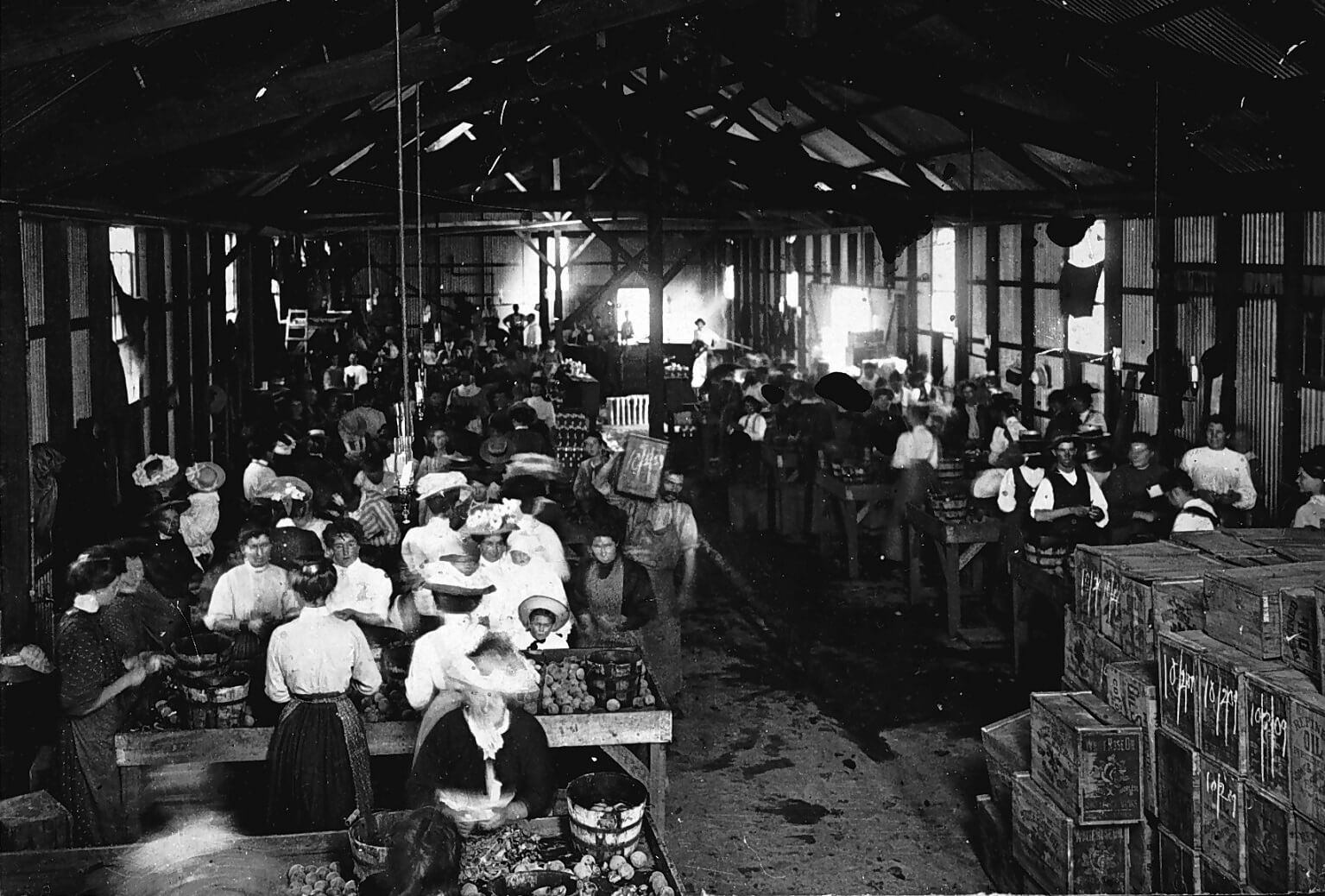

Fruit processing was another important industry, assisted by the irrigation schemes that expanded productive acreage from the 1880s. The Closer Settlement Acts of the late 1890s also saw an increase in intensive agriculture on small holdings. Large companies like the Rosella Preserving Company or the Henry Jones Cooperative helped to supply a growing export market in preserved fruit and vegetables, sauces and pickles in the years around the First World War. Many of these factories were little more than large, corrugated iron sheds, but they provided welcome employment in rural areas for both men and women.

The conditions in this factory were basic and involved workers standing all day in crowded conditions. Perhaps the photograph was something of an occasion though, because several of the female workers are wearing elaborate hats, while one woman seems to have brought along her young children.

Henry Jones IXL factory, c. 1927. Gelatin print.

Courtesy State Library Victoria

Female employees preparing peaches and apricots for canning.

‘Er name’s Doreen’: the girl from the pickle factory

As the nineteenth century progressed more women sought employment in Victoria’s growing industrial sector. Although women were paid only about half the wages of male workers, many women expressed a preference for the ‘freedom’ of the factory, as an alternative to domestic service and the constant oversight of a mistress. Philosophical debate about the moral risks associated with female employment in factories was a constant theme in the later decades of the century. There was often a not-so-subtle implication that factory girls working alongside men all day were easy prey, and that their virtue was open to question. Whether this debate influenced popular poet and author C.J. Dennis is not clear, but he elected to make a factory girl the heroine of his hugely successful verse/novel The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke published in stages in The Bulletin from 1909-1915 and then as a book in 1915. The verse was written in Australian slang and it became immensely popular. The Bloke himself was a larrikin named Bill, who was a member of a gang in Little Lonsdale Street (Little Lon) when he found himself smitten by Doreen. Doreen was a factory girl, whose ‘lurk’ (job) ‘Wus pastin’ labels in a pickle joint’ in Little Bourke Street. The Bloke saw her first at the market, but his usual pick-up line met with a frosty response.

The Intro

Er name's Doreen… Well, spare me bloomin' days!

You could 'a' knocked me down wiv 'arf a brick!

Yes, me, that kids me self I know their ways,

An' 'as a name fer smoogin' in our click!

I jist lines up an' tips the saucy wink.

But strike! The way she piled on dawg! Yeh'd think

A bloke wus givin' back-chat to the Queen….

'Er name's Doreen.

I seen 'er in the markit first uv all,

Inspectin' brums* at Steeny Isaacs' stall.

I backs me barrer in—the same ole way—

An' sez, "Wot O! It's been a bonzer day.

'Ow is it fer a walk?"… Oh, 'oly wars!

The sort o' look she gimme! Jest becors

I tried to chat 'er, like yeh'd make a start

Wiv any tart.

An' I kin take me oaf I wus perlite,

An' never said no word that wasn't right,

An' never tried to maul 'er, or to do

A thing yeh might call crook. To tell yeh true,

I didn't seem to 'ave the nerve—wiv 'er.

I felt as if I couldn't go that fur,

An' start to sling off chiack like I used…

Not intrajuiced!

*Tawdry finery

Bill next encounters Doreen in Little Bourke Street, near where she works, but once again his attempt to speak to her falls on deaf ears. She ignores him.

Once more I tried to chat 'er in the street,

But, bli'me! Did she turn me down a treat!

The way she tossed 'er 'ead an' swished 'er skirt!

Oh, it wus dirt!

A squarer tom, I swear, I never seen,

In all me natchril, than this 'ere Doreen.

It wer'n't no guyver neither; fer I knoo

That any other bloke 'ad Buckley's 'oo

Tried fer to pick 'er up. Yes, she wus square.

She jist sailed by an' lef me standin' there

Like any mug. Thinks I, "I'm out o' luck,"

An' done a duck.

Eventually of course, Bill engineers a proper introduction to Doreen. She agrees to meet him and the romance blossoms. By the end of the book they are married and Doreen has fairly succeeded in reforming her larrikin. Sitting in the garden on a summer’s evening, the Bloke reflects on life and love.

Sittin' at ev'nin' in this sunset-land,

Wiv 'Er in all the World to 'old me 'and,

A son, to bear me name when I am gone.…

Livin' an' lovin'—so life mooches on.

C.J. Dennis The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke. Extracts from The Intro and The Mooch o’ Life. The entire poem can be accessed here.

The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke went on to sell thousands of copies and has never been out of print. It was a favourite for recitation and in time inspired films, musicals, a ballet and theatrical adaptations. Dennis also published a sequel entitled Doreen. Although never as well-known as the Sentimental Bloke, the character of Doreen reflected in these two poems may have helped to create a more positive image of the ‘factory girl’. A glossary of popular slang used in the poems can be found here.