‘Tea may fairly claim to be the national beverage. A large majority of the population drink it with every meal.’

Richard Twopeny, Town Life in Australia, 1883

For much of Australia’s history tea and the teapot presided at family meals. In between, morning and afternoon tea helped keep hunger at bay. A cup of tea was both solace and stimulant, the cure for everything from headache to heartache, or simply a good excuse for the busy housewife to sit and rest for a moment.

Australians of all classes were prodigious tea drinkers. From the 1840s until 1900 our consumption of tea was the highest in the world, averaging 4-5 kilograms per person per year. Thereafter it remained the second highest, after Great Britain. It was not until the 1940s that coffee began to make real inroads into annual tea consumption and tea is still very popular: Australians consumed over ten kilograms per household in 2021. In the nineteenth and early-twentieth century bulk tea was shipped to Victoria in wooden boxes (tea chests) and sold by weight in grocer shops. The chests themselves were only used once and were then sold off for general storage use. Many households kept at least some of their belongings in tea chests, so one way or another tea was very much a part of Australian family life.

Why was tea so popular?

By the early nineteenth century tea was becoming increasingly popular in Great Britain and in the British diaspora. Australia was no exception. Part of tea’s appeal was its durability and the fact that it was light and easily transported. A supply was readily carried from place to place by itinerant workers, and it was soon included in rations for shepherds and other rural workers. These men famously drank their tea from tin cans known as billies, carried about by their wire handles and placed directly on a campfire to boil. Over time they became blackened from the fire outside and from accumulated tannin inside. This was thought to make the water boil faster and to add to the flavour! The billy was later immortalized by Banjo Patterson in his famous poem Waltzing Matilda published in 1895, (and seriously considered in 1977 as a potential national anthem,) but the billy was ubiquitous long before that. Most rural families used billies routinely, to take tea out to workers for lunch or afternoon breaks, or to carry small quantities of milk. City families also had billies, for picnics or, until about the 1940s, to receive their daily milk supply from the visiting milkman. There are many photographs showing billies in use in regional Victoria, much like the one we show here. One of the jobs for children on farms was often to ‘take out the lunch’ to the men and women working in the fields. It saved the workers a walk and no doubt saved the housewife from doing it herself. To judge from the quantity of lunch carried by the Bomball girls, it would have been very difficult for a woman with a young child to manage this alone.

‘Taking out the lunch’, by Bill Boyd photographer, Bimbourie, 1921

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

The three Bomball girls take lunch to their father out working on their Mallee farm. One carries a calico lunch bag, while another carries the substantial billy, probably full of sweetened tea. Boyd recorded that lunch was often called ‘afternoon tea’.

March Family having afternoon tea from a large billy, by unknown photographer, Werrimull South, 1937

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

Frank & Jessie March with their children Reg, Shirley & Walter.

First Nations people and tea

Kulin people encountered tea not long after Europeans arrived and soon developed a taste for it. By the 1840s tea was included alongside flour and sugar in rations offered as part of a strategy to keep the Kulin on reserves out of Melbourne and this continued. Richard Broome records that in 1916 the ration for an adult living on a reserve managed under the Aborigines Act included 110 grams of tea per week, while children received half the adult allocation. (p. 203). Later, as the Board pushed more and more mixed-race people from the reserves, many struggled to feed their families. In the depths of the Great Depression, Dora Green pleaded for rations for herself and her family, then living in Bairnsdale and struggling to find work. She asked for clothing and footwear, but also for flour, tea, baking powder, soap, and jam. This suggests the most basic diet of tea, damper, and jam! At least her request was granted, and she was also given oatmeal, treacle and rice. (p.227)

The teapot

Until very recently tea was brewed from dried tea leaves left to steep (or ‘stew’) in a teapot (or billy). Tea bags did not make an appearance until the 1920s, but the commercial varieties were really a product of the 1960s, after which their use spread rapidly. One scholar has estimated that in the 1960s tea bags accounted for only about 3 per cent of all tea consumed in Britain. It is now over 90 per cent.

Before the 1970s almost every family owned a teapot, and many owned several. They were made of many different materials, from fine china to glazed earthenware, silver (and later silver plate) to tin; and they came in many sizes, from tiny tea pots for one or two cups, right up to huge tea pots (often called tea kettles) used to serve the multitudes at functions. The largest pots required serious muscle power to lift and pour! We show two very different tea pots in the exhibition.

Wealthy families usually owned several tea pots to suit different occasions. Special occasions, like formal afternoon teas or the tea served after a formal dinner, called for a full tea ‘service’. This might be made of fine china, or of silver, but the critical thing was that the component parts matched. It was a ‘set’. This generally meant the tea pot itself (of a generous size), a separate hot water jug, milk jug, sugar bowl and tea strainer (with accompanying saucer). If the set was a china one, there might well be matching teacups, saucers, and plates too, but often these were of a different pattern. Some of the commentary on the topsy turvy world of goldfields Victoria mentioned the mismatching china used by otherwise-respectable hostesses at their tent tea parties, but the sense nevertheless, was that the ritual of tea was a reassuring sign of social order in the midst of chaos. Elizabeth Ramsay-Laye was a wealthy young woman, who arrived in Castlemaine with her husband in 1853. She later published an account of her stay in Victoria.

Soon after we settled in our tent-home at Castlemaine we received an invitation to tea. The party was numerous, the tent, one of the largest in the camp, was lined with green baize; one end of it was fitted up with sofas, arm-chairs, and a grand piano. Small round tables were tastefully dispersed, on which some very pretty ornaments, books, and portfolios of drawings were placed. At the other end there was a large table with cups and saucers of every size and pattern …. The ladies — for ladies they were in every sense of the word — were well-dressed, some even elegantly, in the newest fashions. After tea had been disposed of and the things taken away, we had some vocal and instrumental music, and for a time forgot we were in the land of the diggings. (Ramsay-Laye, pp.18-19)

Books, art, music, and tea, however makeshift the arrangements, were symbols of British civilisation even in the diggings. I suppose the most astonishing thing was that anyone even tried to carry china cups and saucers, (let alone a grand piano,) onto the goldfields at all, given the state of the roads! Clearly, they were important objects. Annie Gray argues that the use of matching teacups, saucers and plates became more important socially as the century wore on: by the 1880s ownership of a ‘tea set’ was a necessity in middle-class households. (Gray 2, p.16)

Tea and consumption

By the early-nineteenth century a plethora of tea ware was available, along with other ‘essentials’ like sugar tongs, for lifting the pieces broken from loaf sugar. Later such tongs were used for lump sugar, always an expensive commodity. Tea ware often featured amongst wedding gifts to wealthy brides, suggesting that they formed an essential part of the household equipment required by a society hostess. Such gifts were all carefully described in the newspaper accounts of these occasions (along with the name of the giver). When Blanch Watson married Bertram Armytage in February 1895 the society couple received no less than four afternoon tea services, one described as a ‘Doulton china afternoon tea service’ and another as a ‘Japanese afternoon tea service’. They were also given a silver kettle, a silver afternoon tea service, a silver cake basket, a silver jam jar, a set of silver afternoon teaspoons, a silver tea caddy, a silver coffee tray and a ‘handsome solid silver tray’, along with other essentials like a crumb scoop and tray and a set of silver grape cutters! Mrs Armytage had an impressive array to choose from when she invited her friends to tea! (The Australasian, 2 February 1895, p.38)

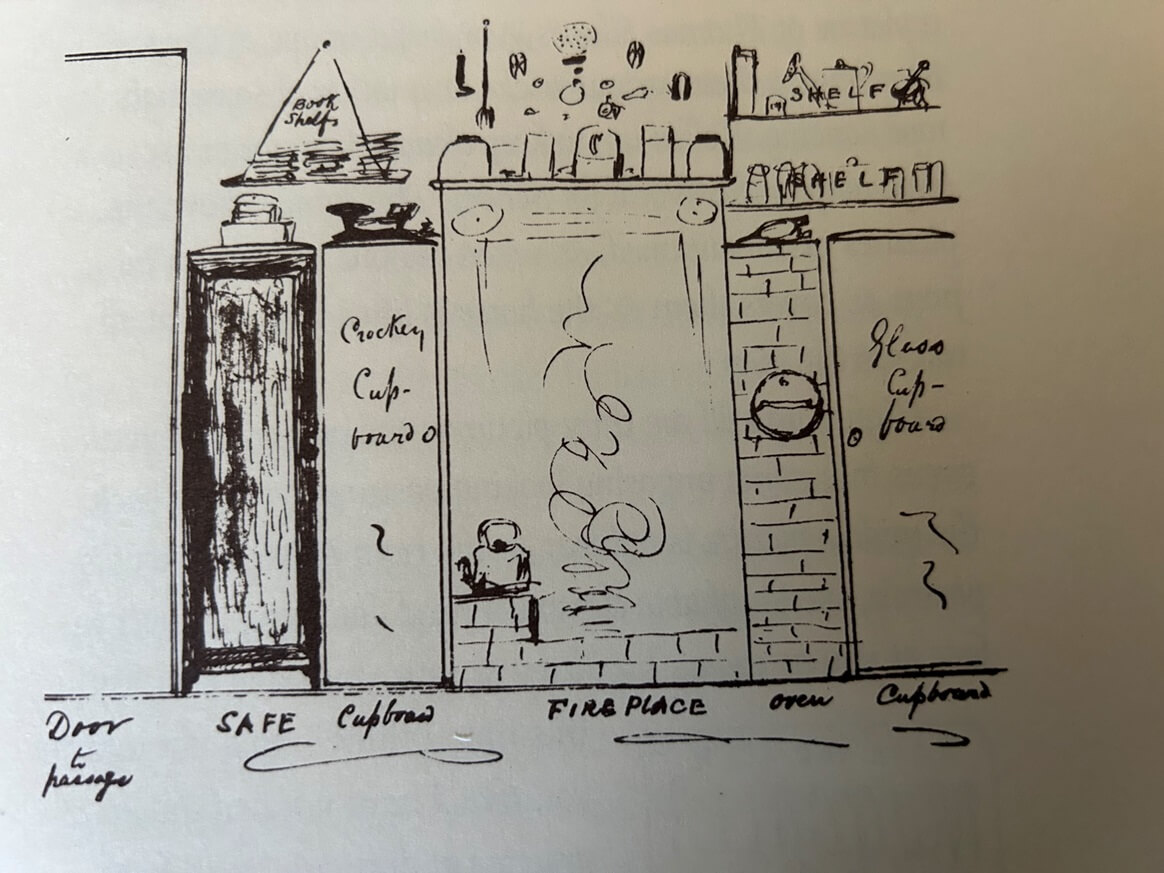

Other more ordinary folk also aspired to own a tea service, if perhaps less grand than some of those listed in accounts of society weddings. In his wonderfully detailed letter to his family describing ‘Our Home In Australia’ (1860) Joseph Elliott paused in describing the belongings stored in one cupboard in the parlour to remark: ‘We do not as yet boast a set of china or it would be in this Cupboard it would be kept’. (p.51) The cupboard in question stored their ‘decanters & other extensive and expensive Glass’. Other requisites for tea were kept on hand in the kitchen, a large room at the back of the house. Here a home-made ‘crockery cupboard’ held their ‘dishes, etc, etc….It is in this that Miss Bep [their daughter, aged 6] several times a day replaces the cup and saucers &c used for breakfast or other meal.’ Above the cupboard and leaning against the wall was their ‘tea tray — not a very decent one — but does us as well as the best.’ The kettle, as expected, sat on the fireplace, while the ‘Teapot’ was stored in a second cupboard by the stove. (pp. 64-5) Joseph’s letter was illustrated with detailed pencil sketches of the various rooms and belongings. One of two showing the kitchen is reproduced here.

Silver teapots or tea services were also considered appropriate gifts to mark significant service, or a long and distinguished working life. Museums Victoria has a very fine tea and coffee service in the collection that was originally presented to William Westgarth, a prominent early colonist, on his return to Britain after seven years at Port Phillip. His fellow colonists engraved the kettle:

Presented to William Westgarth Esquire by one hundred and twenty of his fellow colonists in testimony of their high esteem for his character and appreciation of the benefits conferred on the Province of Port Phillip by his statistical writings and other public services, 1847.

You can see a photo of this tea service on the Museums Victoria webpage.

Such presentations remained popular. In 1872 the retiring town clerk of Ballarat East was presented with a ‘very elegant silver tea service, as a memento of the esteem in which he was held.’ (Argus, 18 January 1872, p.5)

At first silver tea services were made of solid (sterling) silver and were extremely expensive. Mrs. Armytage, as we saw, was presented with a ‘handsome solid silver tray’ on her marriage. Makers stamped every piece with a series of hallmarks, identifying the city of manufacture, the year and often the maker, a system that continues to this day. It guards against forgery and allows for very accurate identification and dating. Of course, only a tiny minority could aspire to own such a service. But from the mid-eighteenth century a process was invented that fused a thin coating of silver to a copper base, allowing for the manufacture of much cheaper products. Ownership of a ‘silver’ teapot was more affordable, if still only for the upper middle classes. Sheffield plate as it was called was replaced in turn by electroplating, a process that was more durable than Sheffield plate, and this soon became the standard process for creating plated products. Some of these producers tried to mimic sterling silver by placing mock hallmarks on the pieces, but by law they also had to include the stamped letters ‘EPNS’ (electro-plated nickel silver), or EPBM (electro-plated Britannia metal) to help to distinguish them from the ‘real’ article. Most of the ‘silver’ teapots sold in Victoria were made from silver plate, including the teapot shown in our exhibition, although they were still an expensive purchase.

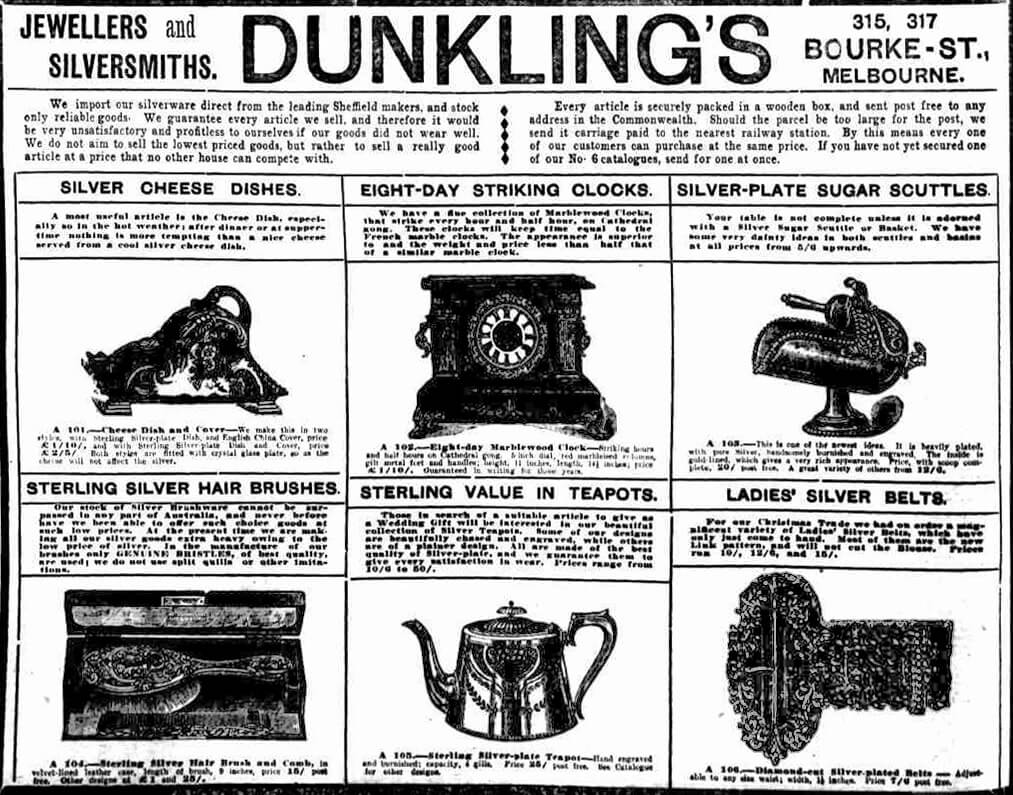

In January 1910 the Melbourne jeweller and silversmith Dunkling’s advertised a similar teapot:

Those in search of a suitable article to give as a Wedding Gift will be interested in our beautiful collection of Silver Teapots. Some of our designs are beautifully chased and engraved, while others are of a plainer design. All are made of the best quality of silver plate, and we guarantee them to give every satisfaction in wear. Prices range from 10/6 to 60/-.

Articles like these were far out of the price range of ordinary working people. In 1908 the Federal Arbitration Court famously nominated 42 shillings per week as a ‘fair and reasonable’ minimum wage, but most workers earned less. Silver teapots were destined for the villas of Melbourne, rather than the cottages.

Advertisement placed by Dunkling’s of Bourke Street Melbourne, The Australasian, 8 January 1910, p.12.

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Everyday teapots were made of much cheaper materials. Some were manufactured from enameled metal, including pots designed to sit directly on a primus stove or gas ring. We show one of these teapots in the exhibition. This is a large teapot, used on the Mont de Lancy farm for many years. Everyday metal teapots were also made from Britannia metal (tin with small amounts of antimony and copper to give it a silvery look), or simple tin. Britannia metal teapots were advertised in the The Age on 31 January 1870 at prices ranging from 4/6d to 20 shillings. (p.1)

Everyday teapot, enamelled metal, made to sit on a primus or other stove, c. early-twentieth century.

Courtesy Mont De Lancey

Ceramic teapots

Like their metal counterparts, ceramic teapots varied hugely in quality and therefore price. Most of the large English potteries made teapots, along with tea sets (matching sets of cups, saucers and plates) and these were imported in large quantities to Victoria. At the top of the hierarchy were the large porcelain factories, manufacturers like Worcester, Spode, or Wedgwood, who produced English ‘porcelain’ goods. At first English potters were unable to replicate the desirable hard-paste porcelain made in East Asia (and from the early-eighteenth century at Meissen in Germany, or mid-eighteenth century at the Sèvres factory in France). But from the 1740s English potters began to experiment by adding bone ash to their soft-paste porcelain mixes, creating a hard paste later known as ‘bone china’. A strong ceramic material, famous for its translucency and ‘whiteness’, bone china was soon adopted by most of the English manufacturers. At last, the English potters had a product to rival those of their Asian and European counterparts. Most of the large English potteries exported their wares to Victoria, but regular consignments of porcelain teapots and other tea ware were also received from China and Japan. The craze for ‘chinoiserie’, so popular in Britain, was also exported to Victoria, via direct imports and through an interest in English tea ware made in the Chinese or Japanese style, as in the tea set from Mont de Lancy shown below.

One style derived from old Chinese porcelain was blue and white printed ware. The design known as the ‘willow pattern’, was enduringly popular, and indeed still appears in catalogues today. It involved applying a printed design by transfer to an unglazed ceramic base, then glazing the whole to preserve the pattern from wear and tear. The capacity to make underglaze transfer ware was developed in England in the 1750s and was used by most of the Staffordshire potteries in the following century. Blue and white china was extremely popular and has been found in archaeological sites dating from the 1840s in Melbourne, on the goldfields and in shipwreck material. The cup shown below was excavated from the inner-city area known as Little Lon in the 1880s. Other popular patterns in the nineteenth century were floral designs, sometimes with gilded rims.

Teacup, blue & white transfer ware, reassembled from fragments, 1805-1880.

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

A matching saucer was found nearby.

Everyday china teapots were usually made of sturdy materials, generally in a glazed earthenware or stoneware. ‘Old brown’ teapots were popular for a long time, as seen in the advertisement from the Argus of 1916 shown here. These teapots were shipped in regular consignments to Victoria, as one story told in the Queenscliff Maritime Museum makes clear. The clipper ship Light of the Age made regular voyages between Liverpool and Melbourne from the mid-1850s. However the final voyage in 1868 ended in disaster, when the ship grounded leaving port in Queenscliff. According to passenger accounts, both the captain and several other crew members were drunk and failed to understand the pilot’s signals. While the passengers were rescued, much of the cargo was lost, including a case of brown teapots. As the museum’s label records: ‘For many years every Queenscliff household was the proud owner of a brown teapot from a case of the cargo strewn along the coast’. (Recorded 18 January 2024) Other items recovered by archaeologists from the wreck can be seen on Victorian Collections.

Argus 26 April 1916 p. 1

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

The tea caddy

Another popular wedding gift was the tea caddy. This was a container, often in a box shape, designed to hold tea. A silver tea caddy was amongst the gifts received by Blanch Armytage in 1895, but tea caddies were made from many different materials. Finely carved wooden caddies were popular in the early decades of the nineteenth century and many fine examples survive in museum collections. The Age reported that several tea caddies made from local wood were exhibited at the Sandhurst Exhibition in 1866. (Age, 14 September 1866, p.5) The great advantage of these caddies was that they could be locked. In the early decades, when tea was expensive, the best tea might well be stored in a locked tea caddy, with the key held by the mistress of the house on her chatelaine — an article of dress worn at the waist and containing small useful items, like keys, tiny scissors, or a watch, all suspended from chains. Later examples often included cosmetics. Tea caddies were also made from japanned metal and in the twentieth century resembled decorative tins. A tea caddy made from tortoiseshell was even advertised for sale in the Argus in 1860. (31 May 1860, p.3) Ordinary folk repurposed tins or jars to store their tea. Amongst many sundries on the mantlepiece above the stove in Rebecca and Joseph Elliott’s house in 1860 were two ‘Pot Preserved Ginger Jars: the one at the right holding coffee, & the one on the left tea’. (Elliott, p.66) Articles of furniture that resembled tables, with tea caddies on top, were also popular and were called teapoys. When the governor’s second daughter Sylvia Madden married Clement Vallange in 1898 one of their wedding presents was an ‘Indian tea table’. This may well have been a teapoy. (Australasian, 20 August 1898, p.44)

Tea caddy owned by Elizabeth Russell, polished wood with inlaid edging. c.1865.

Reproduced courtesy Whitehorse Historical Society

Elizabeth Russell married in 1865. The caddy included two paper-lined compartments and was lockable.

The tea scoop

Tea was often measured from a tea caddy using a tea scoop, yet another article of tea ware popular in the past. These were large spoons with shallow bowls and short handles, useful both for opening tins of tea and for measuring several spoons of tea at a time. I still have my grandmother’s tea scoop, which I use every day. It is Australian, made of brass and has a moulded design of gum leaves and gum nuts on the bowl and handle.

This scoop was used by my paternal grandmother, Gertrude Anderson, by my parents Rae and David Anderson and is now used daily in my kitchen. The photographs show that it is well worn. My grandmother died when I was five and I have only fleeting memories of her. This tea scoop is a tangible link with a shared past.

Shall I be mother?

While both sexes drank tea, often in copious quantities, its social consumption was soon presided over by women. Tea drinking as an opportunity for socializing was well established in Britain before 1830 and was imported to Australia along with other social customs. It was usual for the hostess of any gathering to pour the tea, which was then handed to her guests by a servant (where present). In a family setting, convention assigned this role to the wife and mother, who ‘presided’ over the tea table, poured the tea, and distributed it around the table as required. She also oversaw the manners of those present. Later, when tea rooms became popular additions to urban environments, women might negotiate the pouring role. It was polite to ask: ‘Shall I pour?’, or, more humorously, ‘Shall I be mother?’ At home tea might serve any number of purposes, from an excuse to sit down, to an opportunity to socialize children. Middle-class children learned their tea manners from other adults present long before they ventured into the wider world.

Tea was often served in the garden if the family had one. This photograph shows the Stewart Family at Warracknabeal, c. 1900s. Here, even quite small children have cups, while the table is covered with a fringed ‘tea cloth’ embellished with extensive drawn-thread work. The tea kettle, or large teapot, may be resting on a small primus stove to keep the brew hot.

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

How do you take your tea?

In the nineteenth century most people drank their tea black, but with sugar. Although tea drinking alone did not drive the national consumption of sugar, it undoubtedly contributed, and in the 1800s Australians also led the world in the consumption of sugar. In 1890 we consumed just under one kilogram of sugar per person per week (45.4 kilograms per year). No doubt the jam factories accounted for some of this, but it is still a huge amount of sugar! Our annual consumption of sugar peaked in 1951 at a whopping 57 kilograms per person: it is now about 43 kilograms. Tea was considered a mild stimulant and a ‘refreshing’ drink in the Australian climate, but its energy component was no doubt boosted considerably by the generous addition of sugar. No wonder both housewives and farm labourers found that their well-earned cuppas gave them a ‘boost’ of energy.

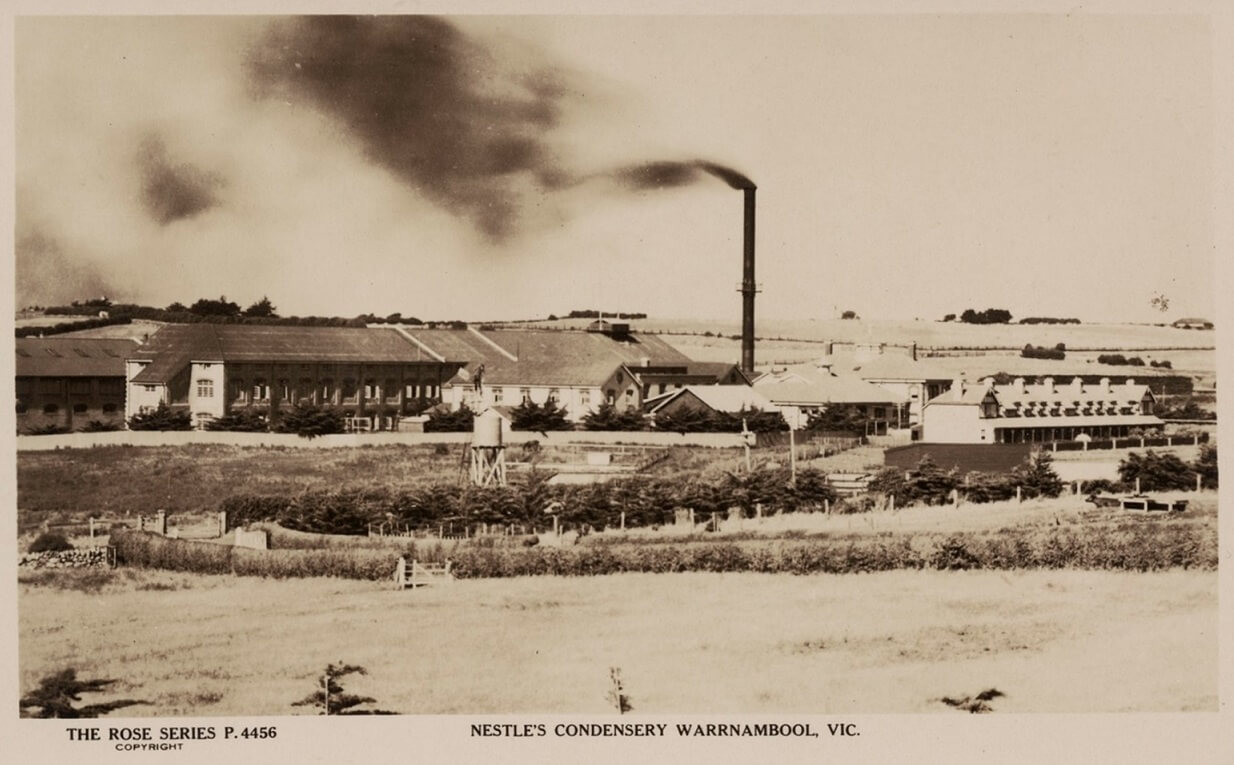

After 1900 more people began to drink their tea with milk (and sugar). The earlier preference for black tea (that is tea without milk) may have reflected the fact that before refrigeration it was difficult to keep milk fresh. The quality of milk sold in cities also improved in the twentieth century, with better hygiene and a crackdown on adulteration. In the meantime, a new milk product appeared that promised to keep fresh longer — this was condensed milk, a product made of sweetened milk from which much of the water had been removed. It was first marketed from the mid-nineteenth century but increased in popularity after its use in the American Civil War. Condensed milk was sold in tins and was useful in households without iceboxes, or other capacity to keep fresh milk from spoiling. Blainey reports that in the 1900s some households preferred it to fresh milk, believing it to be free of infectious contaminants. (p. 254) In 1883 the Victorian government proposed to place a tax on imported condensed milk hoping to bolster local manufacture. In opposing the tax, one correspondent to the Argus stressed that this would impact unfairly on the poor who often could not afford fresh milk and depended on condensed milk to feed their infants. He also suggested that 120,000 tins of condensed milk were consumed in Victoria in the previous year. (The Australasian, 22 September 1883, p.25) The availability of local condensed milk undoubtedly increased after Nestlé opened the largest such manufacturing plant in the world at Dennington, near Warrnambool in 1911.

‘Nestle’s Condensery Warrnambool, Vic.’, undated, unknown photographer

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

All the tea in China

The earlier habit of drinking black tea may also have followed the custom of tea drinking in China, which had a monopoly on global tea exports until later in the nineteenth century. At first all tea imported into Victoria perforce came from China, mostly via British tea merchants. Britain’s dominance in the global tea trade followed its success in the so-called Opium Wars, (1839-42 and 1856-60) which forced Imperial China to allow British merchants to trade in opium to address the trade imbalance created by tea imports. Not content with dominating trade, the mercantile British also sought a stake in the production of tea, and eventually managed to smuggle enough plants out of China to establish their own plantations, initially in Assam, then later in Sri Lanka (then known as Ceylon) and elsewhere. By the late-nineteenth century these plantations were sufficiently developed to supply world markets. Gradually, Australians came to prefer ‘Ceylon’ tea to ‘China’, ostensibly because the Chinese product was often adulterated, and because Ceylon tea was said to produce a stronger brew. Whether there was any truth in the rumours of adulterated Chinese tea is difficult to judge, but certainly late-nineteenth century Australian society was well-primed to believe anti-Chinese stories and to accept the narrative of British plantation owners that their product was superior. Whatever the reasons, from the 1880s Ceylon and Indian tea replaced China tea in consumer preference.

Packaged tea

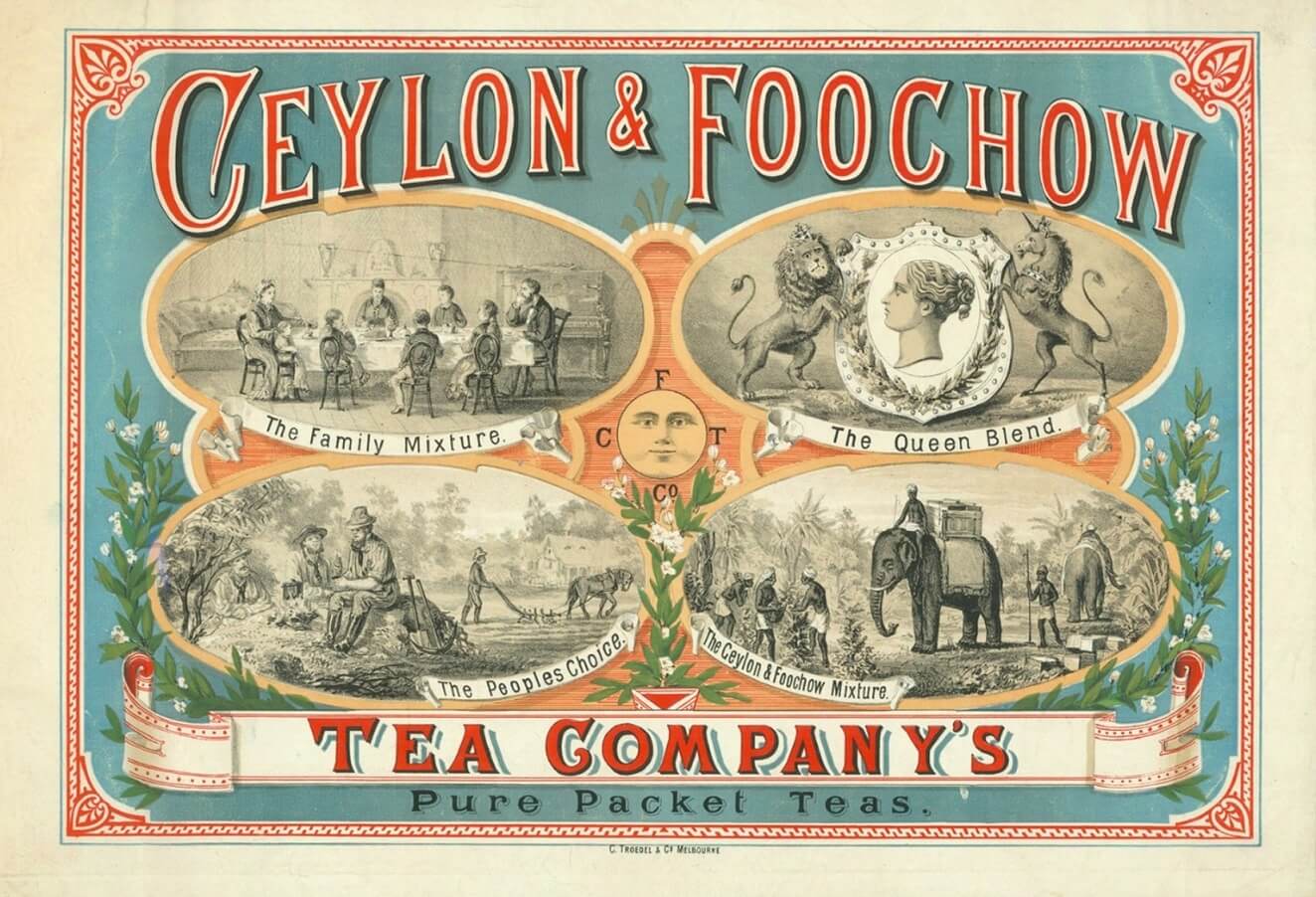

Tea merchants also began to package their tea in decorative tins and pre-weighed packages, with attractive printed labels. Prominent lithographers like Troedel & Co were commissioned to design colourful labels, which helped rival products to attract customer attention. Some companies, like the Ceylon and Fouchow Tea Company, sourced their tea from both the Sub-Continent and China, but gradually Chinese tea varieties became a minority drink. Consumption patterns narrowed in response. Whereas earlier in the century Victorians drank several varieties of tea, including black, green, even white and Oolong, by the late-nineteenth century the ‘standard’ drink was black leaf tea, with sugar (and with or without milk).

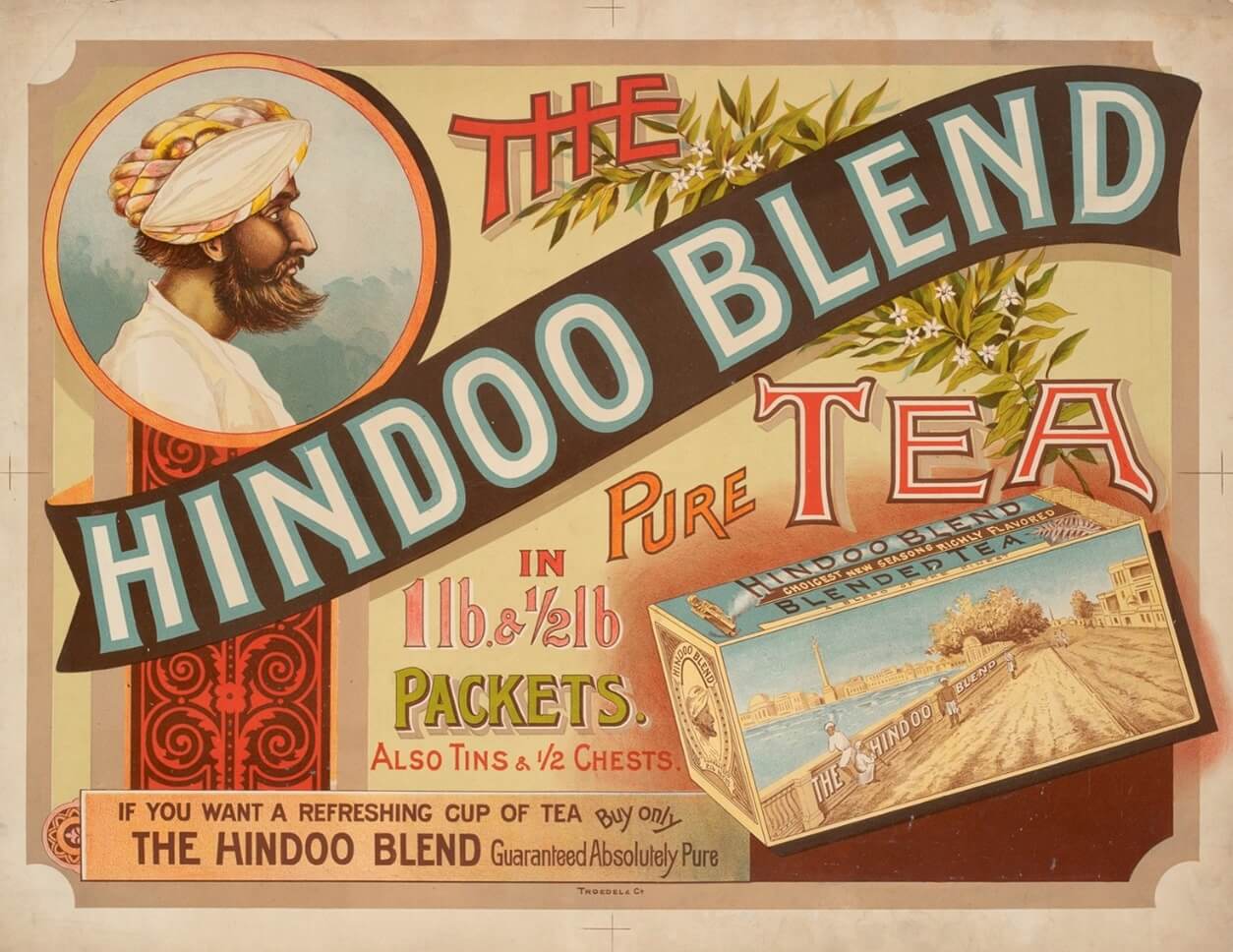

The Hindoo Blend Pure Tea, Troedel & Co., lithographers, 1880-1890

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

The marketing seems to be appealing to doubts about the ‘purity’ of alternative brands.

Poster for Ceylon and Foochow Tea Company’s Pure Packet Teas, by Troedel & Co., lithographer, c.1880-90

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

The iconography on this poster is interesting, suggesting that tea was increasingly promoted to market segments — in this case ‘The Family Mixture’, ‘The Queen Blend’, ‘The Peoples [sic] Choice’ and ‘The Ceylon & Foochow Mixture’. What, if anything, differed between the mixtures is not clear, but certainly the image for the Family Mixture suggests that the children joined their parents in drinking tea.

A drink for the whole family?

That children began drinking tea quite young is suggested in many photographs of the late-nineteenth century. Children tucked into cups of tea, with generous slabs of cake, at picnics, as shown in the photograph of the Stephenson boys at Merrigum in 1910. Note that the boys have both china cups and lacy napkins to accompany the cake piled on their plates. Or they joined their families at afternoon tea in the garden, carefully balancing china cups on saucers, and learning the elaborate etiquette that would accompany such events as adults.

‘Frank Stephenson enjoying afternoon tea with his brother, Merrigum, Victoria’, c. 1910, by Lilian Louisa Pitts photographer

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

Note the large billy nearby.

Beckett family, Charlton, by Thomas Beckett photographer, 1891

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

Thomas Beckett (in his militia uniform), Kate Beckett and their three children George (b. 1884), Nellie (b. 1885) & Lawrence (b. 1890). Both George and Nellie have their own cups, though neither look very enthusiastic about it. They had probably been told to stay absolutely still for the photograph. The tea service is an elaborate one, the teapot possibly Wedgwood’s famous ‘jasper ware’, with fine china cups, saucers, and tea tray.

Play tea parties

Children also played at taking tea, using miniature tea sets if they had them. Here Molly and Arthur Farrell played with a miniature tea set in Heidelberg in 1907.

Molly & Arthur Farrell having a tea party in the backyard of their Heidelberg home, by unknown photographer, 1907

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

Dorothy Fiddes having a tea party with her two dolls, by unknown photographer, c. 1934.

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

Dorothy seems to be drinking from a full-size cup.

Kathleen & Alan Gawler having a tea party, Hawthorn, by unknown photographer, 1925

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

Miniature tea sets were made in the nineteenth century by all the major potteries and were exported to Australia. Their fragility meant that children were sometimes only allowed to play with them on special occasions, but the advent of plastics in the twentieth century made children’s tea sets more widely available and much cheaper!

Some lovely children’s tea sets can be found in museum and historical society collections around Victoria, including those shown here.

Child’s teaset, hand-painted ceramic, belonged to Ida Baker, 1912

Reproduced courtesy Mont De Lancey

Dolls ceramic tea set, c. 1920s

Reproduced courtesy Orbost & District Historical Society

Tea rituals

As tea drinking spread throughout the community, rules and rituals evolved to guide in its preparation. These varied widely but one adage that has survived to the present is the direction to use one teaspoon of tea per person, and one ‘for the pot’. Beyond that, preferences varied widely. But even this ‘old rule’ was questioned from time to time. The ‘Household Hints’ column in The Age in November 1915 dismissed it as ‘absurd’:

since it ignores the size of the pot and the quantity to be drunk by each person. A more accurate and reliable rule is one and a half spoonful to a pint of water, or two and a half to the quart if a large teapot is used. If a good quality of tea is used the quantity may be reduced to two spoonfuls to the quart.

The Age, 17 November 1915, p.12.

Since the context for the column was the high price of tea in wartime, it was perhaps not surprising that the author suggested economy!

Over the years, debate has surrounded most aspects of tea making. Should the water be boiling, or just off the boil? Must it be water ‘freshly boiled’ and, most importantly, should the teapot be warmed before the tea is added. (Most seemed to agree on the necessity of warming the pot.) Later, when tea with milk was more common, equal controversy surrounded the question of when the milk should be added. Should it be placed in the teacup first (warmed or otherwise) or added afterwards? There were passionate adherents of both, including none other than the literary giant George Orwell, who published his 11 rules of tea making in 1946. They can be found here: https://www.orwellfoundation.com/the-orwell-foundation/orwell/essays-and-other-works/a-nice-cup-of-tea/ . Orwell, for the record, added milk to his tea after pouring.

Advice on making a ‘good cup of tea’ appeared from time to time in the newspapers. A couple of examples, from different time periods, are reproduced here.

The Australian Women’s Weekly, 22 August 1936, p.47

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Ruth Frost’s advice in The Australian Women’s Weekly (1936) is interesting on two counts in particular — the suggestion that two teapots should be used (both of which were to be warm and dry) and the insistence that the teapot should be brought to the kettle and not vice-versa, thus ensuring that the water was boiling. Orwell also insisted on this point. Making the tea in the first pot, then pouring it into the second may have been a strategy for containing the tea leaves and preventing the tea from further ‘stewing’. Many other rituals evolved to deal with errant tea leaves, including rotating the teapot both clockwise and anticlockwise. I could never get this to work, but perhaps I never developed the knack! Other writers suggested using little muslin bags, anticipating the later development of tea bags. Modern tea pots with inbuilt strainers are a great boon, though I’m sure that Orwell would disapprove. He rejected the idea of containing the tea leaves by any means!

Tea etiquette

How tea was served and consumed attracted its own set of rules, though like all such social conventions, they changed over time, and probably only ever applied in limited social circles. There is some indication that eighteenth-century tea drinkers sometimes drank from the saucer, perhaps as a means of cooling the liquid, but this was considered decidedly poor form later. ‘Slurping’ tea was also bad manners and middle-class children were corrected if they did so. Beyond that were the many conventions of custom and practice that marked the élite from the rest, often played out at the ritual consumption of tea on social occasions. Whether and when tea should be served to visitors was a case in point. The élite activity of paying and receiving calls was imported to Victoria along with many other social conventions and primarily involved women. Penny Russell has described some of its intricacies in A Wish of Distinction. (pp. 50-55) Essentially it was a means by which élite women determined who would and who would not be accepted into their social circle, although it is clear that in some circumstances the man of the house was expected to set the ball rolling. Who can forget the opening chapter of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice (first published 1811), when Mrs. Bennet, with five daughters to marry off, begs her husband to call on the newly-arrived (and wealthy) bachelor in the district: ‘Indeed you must go’, she pleads, ‘for it will be impossible for us to visit him, if you do not.’ (chapter 1) Paying and receiving calls continued to engage wealthy women until well into the twentieth century, with elaborate rules determining the sequence to be followed, the length of any visit, and whether refreshments (generally tea) should be served. The arcane rules of these encounters were determined by the few to exclude the many and were generally learned by wealthy young ladies by accompanying their mothers on these tiring (and sometimes tedious) afternoons. It was at such gatherings, and at more organized tea parties, that they practised the art of drinking tea from fragile cups, managing cup, saucer, and plate with appropriate delicacy, and avoiding such other social solecisms as prevailed at the time.

Afternoon tea

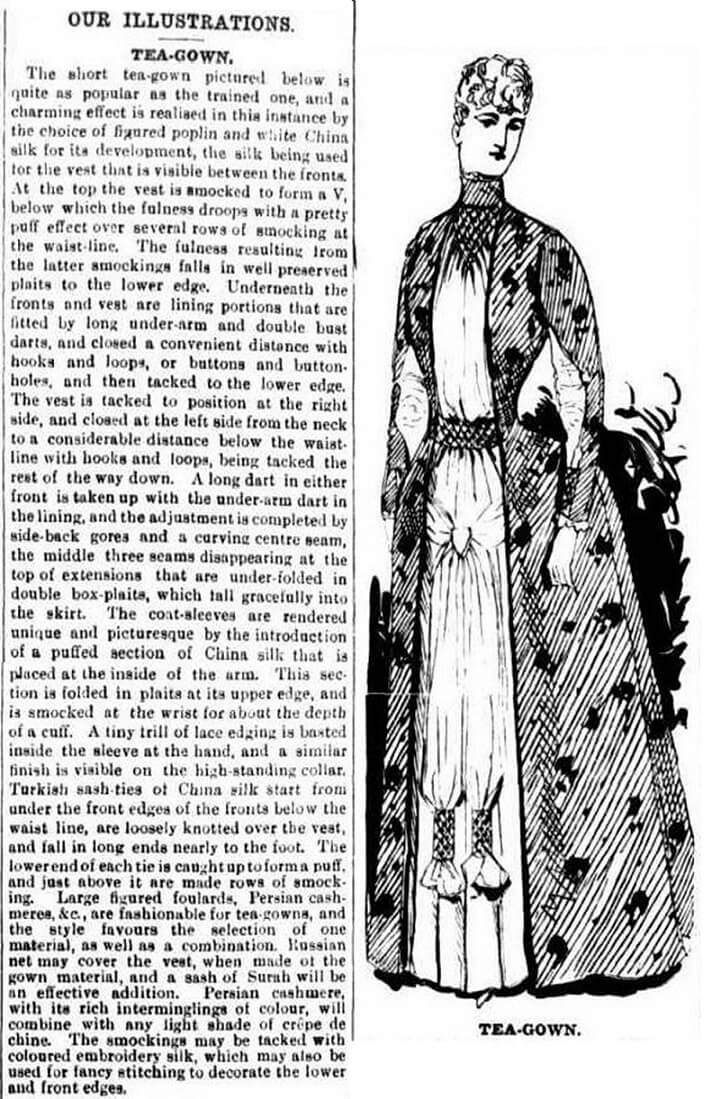

By the late-nineteenth century tea parties were an established form of élite entertainment, often reported in the local newspapers. A new form of costume appeared for these occasions, the ‘tea gown’. Initially this resembled afternoon dress in its cut and style, but later appeared more like a less-formal dinner gown.

The Australasian, 18 August 1888, p. 9

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Up-to-date Tea Gown, The Australasian, 10 October 1914, p. 40

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

For ordinary folk, tea was a more relaxed affair, often consumed at the kitchen table or in the garden, if a family had one. Just when Victorians began to observe the ritual of ‘afternoon tea’ is not clear. One article in The Australasian of 1882 described it as ‘quite a modern luxury’, but implied that many were by then thoroughly addicted to it. (2 December 1882, p.3) Bill Boyd’s memories of Bimbourie in the 1920s however, suggest that lunch and afternoon tea were sometimes conflated, at least amongst those working on small farms. Not for them the luxury of an additional extended break for tea! I did chance on one interesting little tidbit of information, as often happens when trawling through Trove, and this concerns the origins of the break for afternoon tea at the cricket. In 1898 The Age published a snippet under the heading ‘AFTERNOON TEA AT CRICKET/ An Australian custom’. It went on to report that English cricketer Lord Hawke had:

delivered a speech on cricket in which he condemned the Australian practice of allowing an interval in the afternoon’s play for tea. Lord Hawke expressed the hope that English cricketers would avoid the adoption of this practice.

(The Age, 6 May 1898, p.5)

Cricket historians may be able to confirm whether this was indeed a peculiarly Australian contribution to the rules of cricket.

Tea and cakes

By the 1890s local newspapers published regular columns of recipes for cakes and biscuits to serve at afternoon tea. One of Queen Bee’s columns in 1897 printed recipes for ‘hot cakes’, including scones, dropped scones, soda scones, oat cakes and ‘tea cakes’. (The Australasian, 1 May 1897, p.41) By the 1920s the same newspaper reported a change in afternoon tea tastes: ‘A few years ago the little savoury was unknown at afternoon tea, but modern taste often prefers it to the sweeter cakes and biscuits.’ The author proceeded to offer some recipes in ‘answer to special request’ for savoury puffs and eclairs. Some of the suggested fillings seem more than a little odd to contemporary taste. They included grated nuts and shredded celery, mixed with whipped cream seasoned with salt and pepper; or pounded anchovies mixed with a little whipped cream or mayonnaise, and garnished with chopped capers. Additional advice was offered to the hostess/cook:

It must be remembered that these savouries must be kept as small and dainty as possible. No guest desires a huge case of real ‘cream puff’ size, filled with a bulging mixture: it is both difficult to eat and distasteful. A teatime savoury is not meant to be a ‘meal in itself’, but rather a refreshing trifle which intrigues the palate and gives piquancy to the other dishes. (The Australasian, 18 August 1928, p.70)

Afternoon tea and the post-war woman

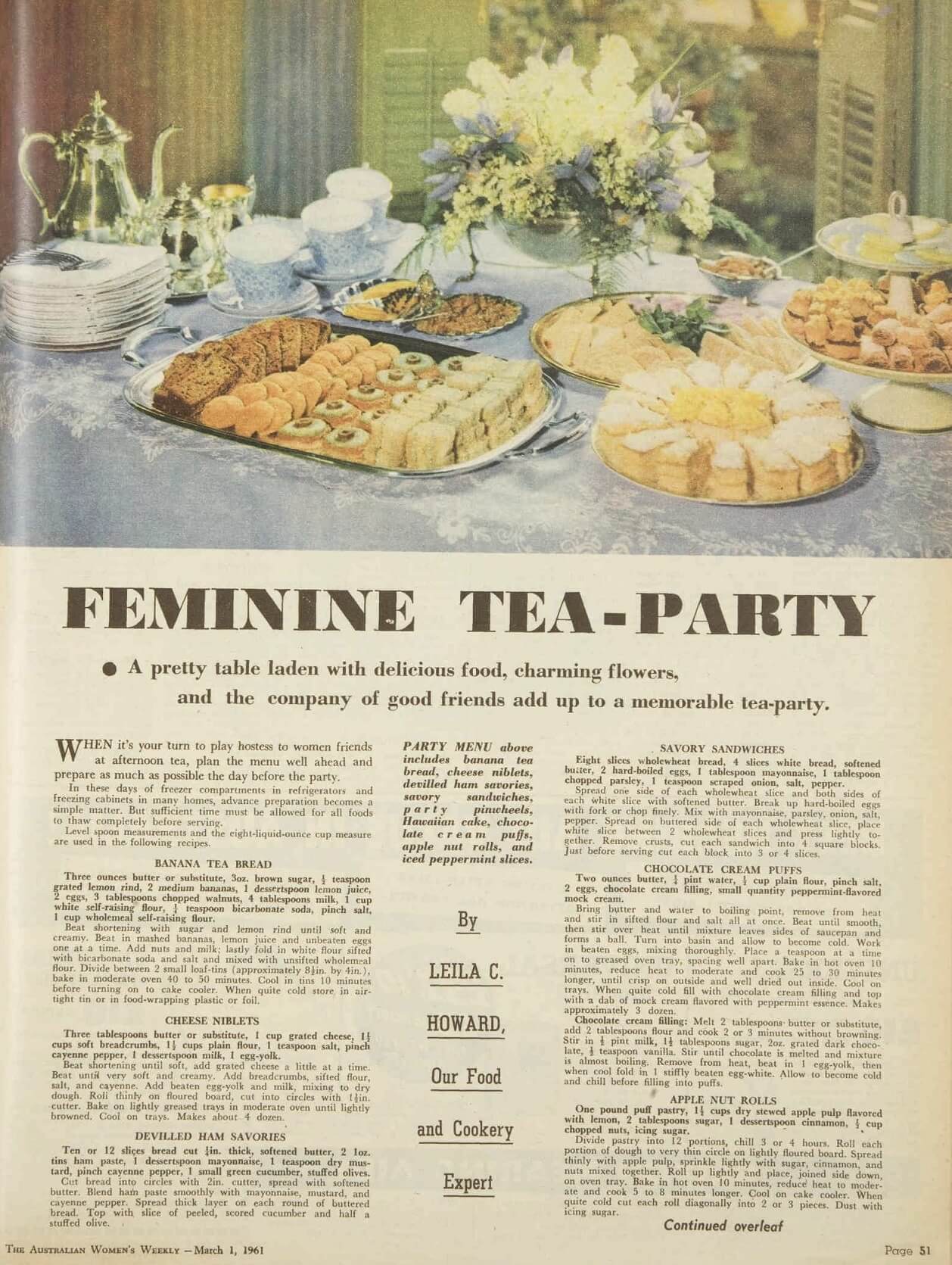

In the 1950s The Australian Women’s Weekly was on hand to offer advice and recipes to the post-war woman, with the added bonus of coloured illustrations to show how to arrange the tea table to best effect. With the restrictions of rationing a distant memory, afternoon tea parties could demonstrate a new abundance. Gone were the old slices of bread and butter: cakes and biscuits, savoury and sweet graced the beautifully dressed table. Afternoon tea parties had long been regarded as a form of women’s entertainment: perforce since men were all working somewhere else! But the Weekly in particular emphasised the ‘feminine’ nature of afternoon tea, in line with post-war rhetoric.

The Australian Women’s Weekly, 1 March 1961, p. 51

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Along with the ‘dainty’ teatime fare, illustrations like this one guided the aspiring hostess in the requisite tea things. In this case they included a silver tea service, a matching set of cups, saucers and plates (each with a small cloth napkin)

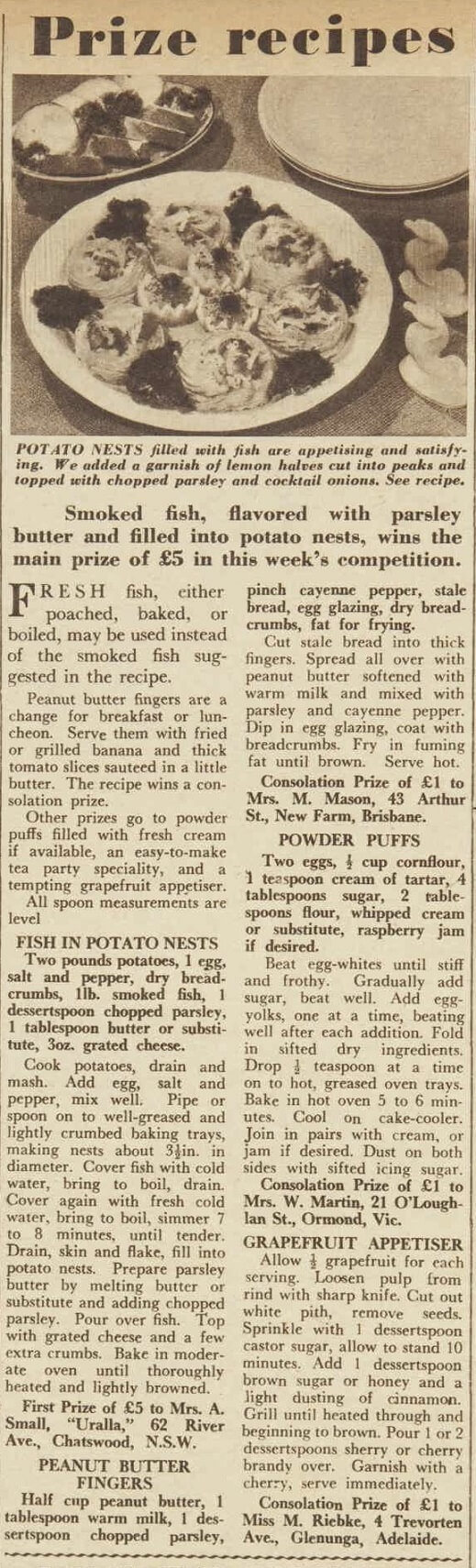

The 1950s and sixties was probably the swansong of afternoon tea. Thereafter it languished somewhat, probably as more and more women entered the workforce. But baby boomer children often have fond memories of those afternoon teas — at family gatherings, tennis afternoons, cricket games or picnics. We hung around the tea trolley hopefully, waiting to swoop on our favourite morsels once the adults had been served. Individual cooks were often famous for particular delicacies. I remember that my mother’s eldest sister, Dorothy, was often prevailed upon to bring along her ‘powder puffs’, little circles of airy sponge filled with whipped cream. She was still making them in the early-twenty-first century for another generation to enjoy. I have her recipe, complete with precise instructions on a complicated baking process devised to work in a post-war electric oven. It was with some surprise and delight that I found a similar recipe in Ottolenghi & Goh’s Sweet collection. This notes that the recipe was contributed by Helen Goh after a recent trip to attend a wedding in regional Victoria, (pp. 82-5) suggesting that powder puffs may well have been another Australian contribution to the afternoon tea table. Indeed, I found a recipe for powder puffs amongst ‘prize recipes’ published by The Australian Women’s Weekly in October 1952. Auntie Dot’s recipe, with instructions, is reproduced below, but I should add that my sister and I amended it to include crushed raspberries with the whipped cream, as do Ottolenghi & Goh. Either way they are delicious little morsels! The Australian Women’s Weekly recipe is shown below for comparison. It mentions using either raspberry jam or whipped cream in the puffs.

Dorothy Fisher’s (née Vickery) powder puffs

2 eggs, separated

2½ ounces castor sugar

1 teaspoon vanilla essence

2 ounces cornflour

1 ounce plain flour

1 teaspoon cream of tartar

½ teaspoon bicarbonate of soda

Beat egg whites then gradually add all sugar. Beat until stiff, then beat in yolks and vanilla. Fold in flours and risings.

Drop dessertspoons of batter on papered tray. Place in oven at 205C (400F) and immediately turn oven off for 6 minutes. Re-set oven temperature to 170 degrees and cook for a further 5-10 minutes. Test by touching. If finger leaves a mark cook for a few more minutes. Bake one tray at a time. The discs will resemble crisp biscuits.

Cool on racks and then fill with stiffly-whipped cream and store in fridge to soften. Dust thickly with icing sugar.

Makes about 15 puffs. The recipe included the instruction not to try to increase the quantities but to make another batch for more puffs.

Oven temperatures are for a standard oven (not fan-forced).

The Australian Women’s Weekly, 15 October 1952, p.42

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

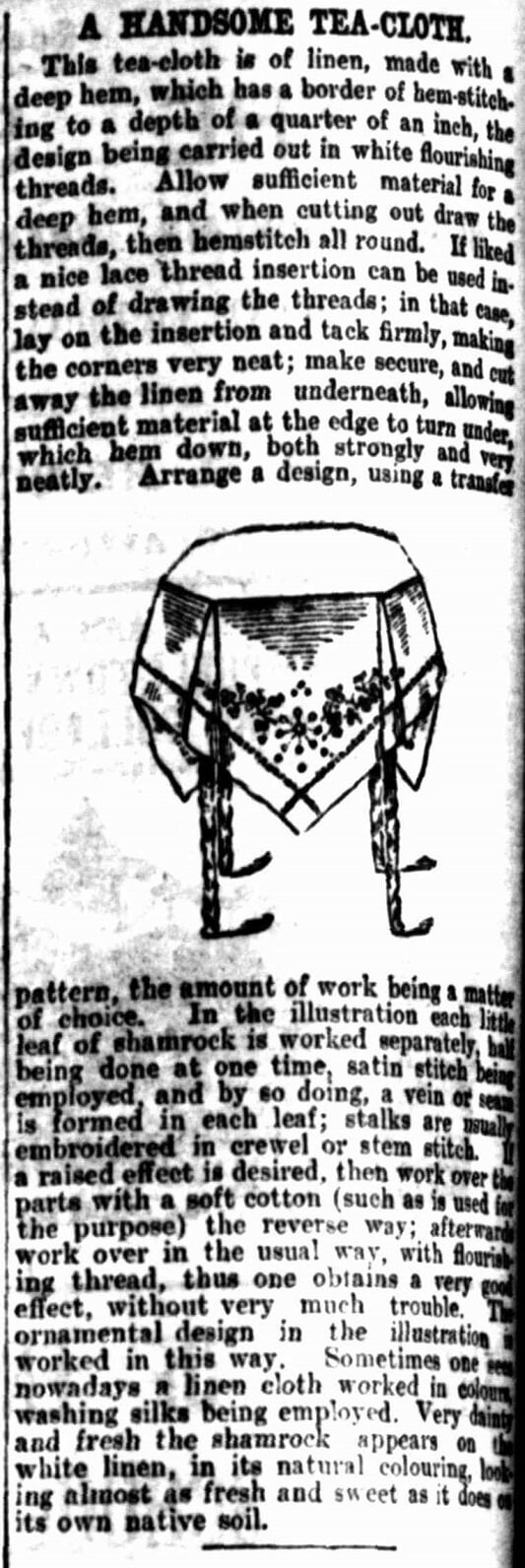

Dressing the tea table

Along with the extensive range of tea ware called for on smart occasions, an aspiring hostess was also required to ‘dress’ the tea table appropriately. From the 1930s The Australian Women’s Weekly provided a visual guide in its many illustrations (see above), but long before this, newspapers provided instructions and patterns for competent needlewomen to make the tablecloths, ‘tea cloths’, doilies and napkins considered essential accompaniments to the tea table. Some of these cloths were minor works of art, exhibiting the varied needlework techniques of the skilled needlewoman: broderie anglaise, drawn-thread work, cutwork and various lace-insertions all appeared on tablecloths, teacloths, and tray cloths in the nineteenth century. From the 1920s embroidery designs using coloured threads became more popular and patterns were reproduced in local newspapers and women’s magazines. Prizes were often awarded for embroidered tablecloths and tea cloths at local fairs and agricultural shows.

Unnamed woman sewing a tablecloth, by unknown photographer, c. 1905

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

The intricate border of this tablecloth features raised embroidery, broderie anglaise and drawn thread work. It took six years to make. The borders were created by pulling threads from the cloth and filling the spaces with different embroidery or lace-making stitches.

Instructions for ‘A Handsome Tea-Cloth’, The Australasian, 3 October 1908, p.48

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Although a relatively simple design, the instructions still assume a high-level of skill in needlecraft.

Sandwich tray cloth with coloured embroidery & crocheted edging, c. 1950s

Reproduced courtesy Kew Historical Society

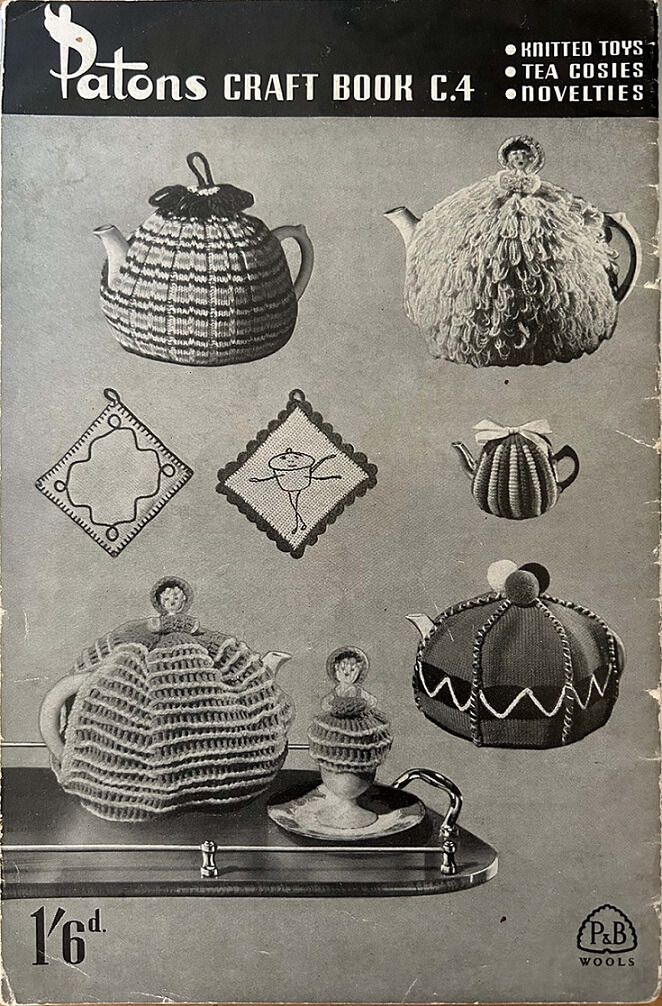

Rather less taxing, but equally essential were the tea cosies, routinely used on tea pots to keep the tea hot. These might be made of embroidered fabric, lined and padded for insulation, but for everyday use were more likely to be knitted or crocheted. Many a child was set the task of knitting a tea cosy as an early knitting project. Families often owned several tea cosies for different sized tea pots and for use on different occasions.

Tea cosy, crochet ‘lace’ with padded blue satin lining, c. 1900-1920

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

Tea cosy, knitted, c. 1950s

Reproduced courtesy National Wool Museum

Knitted by prize-winner Vera Kneale (1901-1990), famed for knitting with one and two-ply wool (very fine) and on piano wire or bicycle spokes as needles. She often entered garments in local agricultural shows in Victoria and NSW.

Much easier were the patterns found amongst my mother’s knitting books from the 1940s, fifties and sixties. These were for the everyday cosies more likely to be found in kitchens throughout Victoria, although I must admit that the instructions for the ‘crinoline’ pattern (with the loops) look very fiddly! We had one that looked remarkably similar to this pattern for the ‘best’ teapot when I was a child, so perhaps my mother used this pattern.

High tea

A variant on the afternoon tea, ‘high tea’ in Australia seems initially to have been a form of entertaining that was half-way between the usual afternoon fare and a more formal dinner. One article in the ‘Ladies’ page’ of the Leader in 1884 suggested that it might be a useful entertainment to offer in the current shortage of servants since it was easier for a harassed hostess to manage. (3 May 1884, p.7) Quite when it assumed its current formula, of an abundance of finger food, comprising scones, sandwiches, fancy cakes and so on it is not clear. One article in a local newspaper suggested that the term was unfamiliar to many attendees at the Ivanhoe Presbyterian High Tea, held in 1916. It was explained that a ‘high tea’ was ‘really a knife and fork tea’. The menu apparently comprised cold ham, ox tongue and salad, scones, cakes, fruit, and ‘bread and butter in abundance’, with tea of course. People ate at tables with their knives and forks. (Heidelberg News and Greensborough and Diamond Creek Chronicle, 10 June 1916, p.2) High teas are now offered by many of the larger hotels in Melbourne, possibly all variants on the ‘afternoon teas’ served at famous hotels like the Ritz. The Ritz however does not use the term ‘high tea’, which it believes is derived from the name given in the nineteenth century to the hot meal eaten by workers at the end of a working day. This, in turn, was often shortened to ‘tea’. The Ritz repeats the popular legend that the term ‘afternoon tea’ derived from the Duchess of Bedford’s practice of consuming a small serve of bread, butter and cake between lunch and her (fashionably late) dinner, begun in 1841. (https://www.theritzlondon.com/2022/09/01/guide-to-afternoon-tea-etiquette/ ) However Annie Gray points to the long history of tea drinking in the afternoon and suggests that the phrase itself derived from expanding cookery and advice manuals in the nineteenth century, rather than from any specific instance. She also argues that the late-nineteenth century used a wide range of terms to describe this repast, some of which were determined by class. (Gray,(1), p.47; Gray (2)), p.19)

The reviving power of tea

Part of the appeal of tea was its alleged capacity to revive flagging energy. Long before the effects of caffeine were fully understood, tea was valued as a restorative, even if at least part of the impact was probably provided by sugar. Commentators were quick to assure consumers that it was a ‘mild’ stimulant of course, to distinguish it from other more harmful drugs like alcohol or opium. But there was always a counter narrative, sometimes reflected in advertisements for products to neutralize the ‘harmful effects’ of components like tannic acid and later caffeine, or serving as alternative drinks to tea and coffee. From 1912 the US required that caffeine be listed as an ingredient in product labels, identifying it as a ‘habit-forming’ and potentially harmful substance, but this narrative rarely focused on tea. Initially it was coffee and then the early Coca-Cola formula that attracted attention.

Ad for Instant Postum from Argus, 30 May 1928, p.15

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

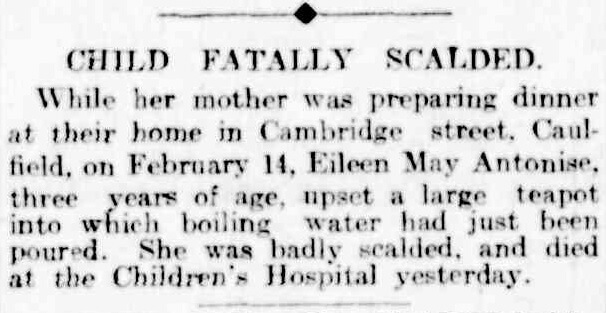

One of the likely health benefits of tea drinking in nineteenth century Victoria was not the leaf itself, but the requirement for water to be boiled in its preparation. At a time when the water supply was far from safe, this may have provided some protection against the various enteric infections that plagued Melbourne until the early twentieth century. Sadly, the boiling water was also a hazard in households in the past and the newspapers are littered with accounts of young children scalded by tipping kettles or teapots of boiling water over themselves, or even of drinking scalding liquid from teapot spouts.

Ironically, households also used cold tea as a remedy for minor scalds and burns: it is remarkably (and immediately) effective, but only so long as the affected part is immersed in the tea.

A ‘nice cup of tea’ as solace or celebration

Along with its everyday appearance at mealtimes, a ‘nice cup of tea’ was often suggested whenever family members or friends were in need of support or consolation. There was comfort in performing the ritual of making the tea, but drinking it was also thought to help restore perspective in the face of troubles. ‘I’ll put the kettle on’ was the recognised prelude to a heart-to-heart talk.

Discover the story of Lena Salau and the hardworking teapot here.

Tea in the English language

Tea and its consumption is now firmly embedded in the English language and in its Australian variants. We might invite a friend home for a ‘cup of tea’ for example, or simply for a ‘cuppa’, or a ‘brew’. Tea itself was sometimes called ‘char’, possibly derived from the Indian ‘chai’, but char is also very like the Chinese word for tea, ‘tcha’. Then there are all the shorthand phrases used to describe how we like to drink our tea. ‘White with one’, means tea with milk and one teaspoon of sugar, while ‘straight black’ means tea with neither milk nor sugar. Both phrases assume tea derived from dried black tea leaves, rather than green tea or other varieties. Other idioms have developed too. It’s ‘not my cup of tea’, means that something is not to our liking; while ‘reading the tea leaves’ means predicting the future, or reading between the lines. I wouldn’t want that ‘for all the tea in China’ we might say, meaning that we really don’t want something and can’t be bribed into changing our minds; while ‘a storm in a teacup’ means a lot of fuss about nothing. Then there are the colloquial descriptions of tea. Tea might, for example, be ‘so weak it’s helpless’, or taste ‘like dishwater’. Strong tea on the other hand, might be ‘strong enough to stand a spoon up in’. There are bound to be more!

Tea or Coffee?

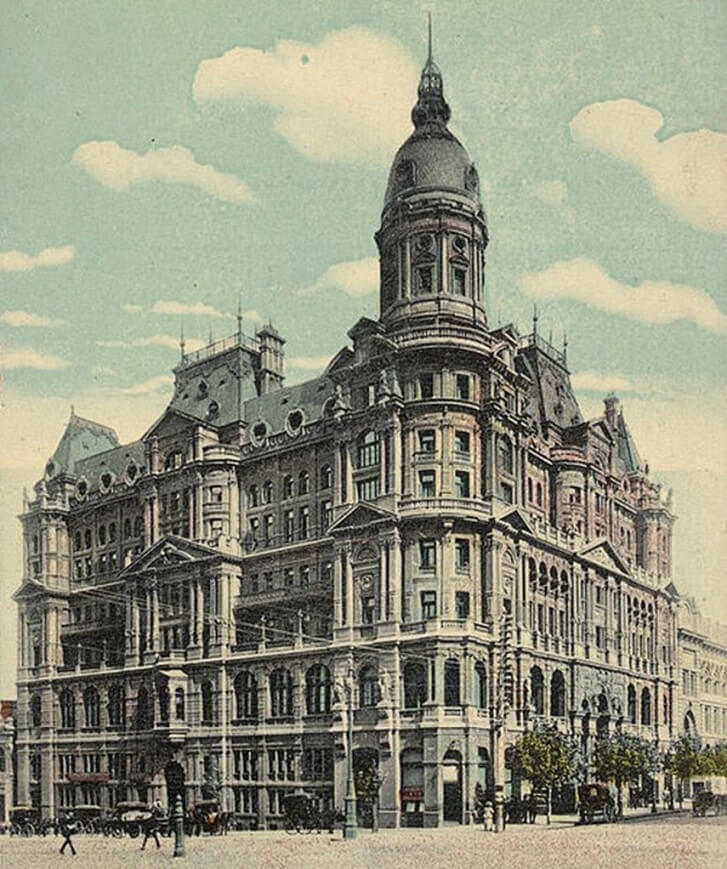

By the 1830s when British pastoralists first arrived at Port Phillip tea drinking was already well established in England. But coffee was also popular. Indeed, coffee drinking was established long before tea became popular, sold in coffee houses in large cities from the mid-seventeenth century. Early colonists certainly drank both tea and coffee, as the silver service presented to William Westgarth in 1847 suggests, but tea consumption was increasingly dominant. Perhaps it was simply easier to prepare, with no necessity to grind beans, or roast them for that matter. In the late-nineteenth century, as the temperance movement gained in strength, so-called ‘coffee palaces’ became increasingly popular. These were large residential hotels that did not serve alcohol. The Federal Coffee Palace, which opened in Collins Street in 1888, was the largest and most splendid coffee palace ever built. It was demolished in 1973. Meanwhile the Grand Coffee Palace in Spring Street survived to become the Windsor Hotel. Although immensely popular in the 1870s and eighties, many of Melbourne’s coffee palaces did not survive the 1890s depression. Some became boarding houses, while others, like the Grand, resumed previous liquor licenses and became hotels.

American troops stationed in Melbourne during the Second World War prompted a revival in coffee consumption. Melbourne hostesses wishing to entertain American servicemen were advised to offer them coffee rather than tea, while other ‘new’ foods like hamburgers also made an appearance. After the war the advent of Nestlé’s ‘instant’ coffee, which was introduced to Australia in 1947, presented the first serious challenge to tea drinking in over a century. It certainly made a cup of coffee a quick and easy alternative, replacing the drink made from coffee essence, a thick syrup that contained chicory, that some favoured at home. ‘Instant’ tea never had the same appeal. But it was the increasing popularity of espresso, introduced by Italian immigrants and sold in cafes in both Melbourne and Carlton, that finally won over many former tea drinkers. Now so-called ‘barista’ coffee is available just about everywhere, even in small country towns.

But however the current craze for barista coffee may have changed the drinking habits of Australians in the last decade or so, tea is still popular: we consumed over 10 kilograms per household in 2021.

Watch Margaret Anderson give a presentation about the Teapot:

References

Jim Bertouch, ‘Taking Tea in the colonies’, Australiana, August 2014, pp. 18-27

Geoffrey Blainey Black Kettle and Full Moon: Daily Life in a Vanished Australia. Penguin Books Australia, 2003

Richard Broome Aboriginal Victorians. Crows Nest, Allen & Unwin, 2005

A.E. Dingle, ‘”The truly magnificent thirst”: An historical survey of Australian drinking habits’. Published online 30 September 2008.

Joseph Elliott Our Home in Australia: A Description of Cottage Life in 1860. Sydney, The Flannel Flower Press, 1984

Geoffrey Godden An Illustrated Encyclopedia of British Pottery and Porcelain. London, Bonanza, 1966

Annie Gray (1), ‘“A Moveable Feast”: Negotiating Gender at the Middle-Class Tea-Table in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century England’, Food & Drink in Archaeology, Vol. 2, 2008, pp. 46-56

Annie Gray (2), ‘”The proud air of an unwilling slave”: Tea, women and domesticity, c.1700-1900’, in Suzanne Spencer-Wood (ed) Historical and Archaeological Perspectives on Gender Transformations: From Private to Public. New York, Springer, 2012, pp. 23-43

Ross W. Jamieson, ‘The Essence of Commodification: Caffeine Dependencies in the Early Modern World’, Journal of Social History, Vol. 35, No. 2, Winter 2001, pp. 269-94

Susie Khamis ‘A Taste for Tea: how tea travelled to (and through) Australian culture’, The Real Thing: Australian Cultural History, Vol. 24, 2006, pp. 57-80

Diane Kirby, ‘“Beer, Glorious Beer”: Gender Politics and Australian Popular Culture’, Journal of Popular Culture, Vol. 37, No. 2, November 2003, pp. 244-56

Anne-Louise Muir, ‘Ceramics in the collection of the Museum of Chinese-Australian History, Melbourne’, Australian Historical Archaeology, Vol. 21, 2003, pp. 42-49

Yottam Ottolenghi & Helen Goh Sweet. London, Ebury Press, 2017

Elizabeth Ramsay-Laye (also Isabel Massary) Social Life and Manners in Australia: Being the Notes of Eight Years’ Experience by a Resident. London, Longman, 1861.

Penny Russell A Wish of Distinction: Colonial Gentility and Femininity. Melbourne University Press, 1994

Stacey Sloboda Chinoiserie: Commerce and Critical Ornament in Eighteenth-Century Britain. Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2014

Linda Young Middle Class Culture in the Nineteenth Century: America, Australia, Britain. Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, 2003, numerous specialist serving dishes and an embroidered tablecloth. A ‘charming’ flower arrangement graced the table.