This is the story of a hardworking teapot — a Robur ‘Perfect Teapot’ like the example pictured above. The ‘Perfect Teapot’ in our story lived for most of its life on a pastoral property in Balranald in NSW near the Victorian border, in a kitchen presided over by Lena Salau. Lena grew up in regional Victoria and married Bill in 1948. The teapot was a wedding present from one of Bill’s married sons and his wife and Lena always treasured it. Silver-plate teapots were expensive items, as we have seen, and this was a generous gesture from a stepson. When they married both Lena and Bill were widowed with children and might have assumed that there would be no more. The unexpected arrival of a daughter four years later was described as a ‘gift’. Their descendants have vivid memories of visits to the farm and remember teatimes around the kitchen table with great affection. They have shared their memories with us. The teapot presided at every meal.

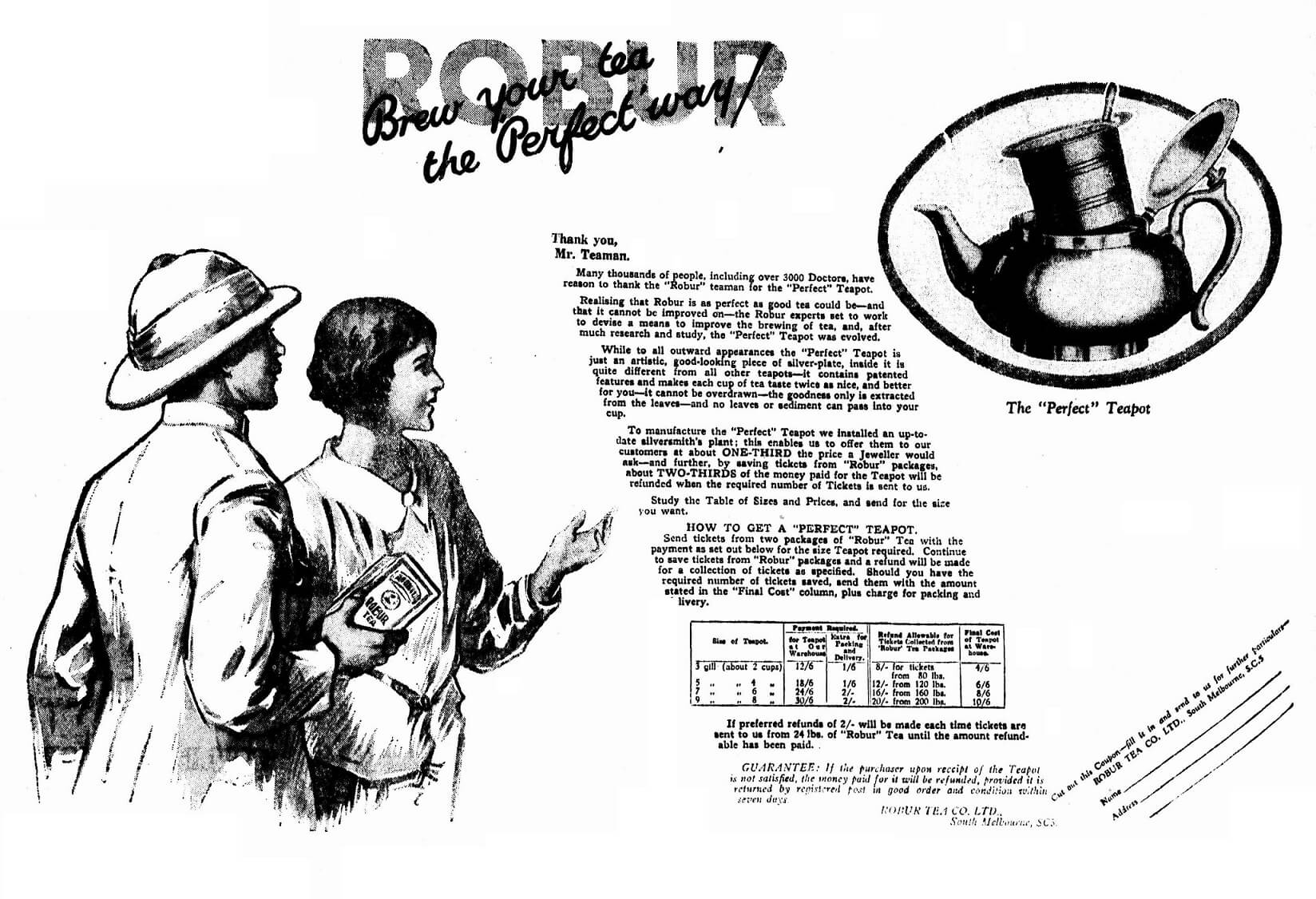

Robur’s ‘Perfect Teapot’ was a clever concept that dealt with two common problems of tea making — the tendency for tea left brewing for too long to become bitter and ‘stewed’ and the annoyance of dealing with tea leaves once the tea was ready. Both problems were eliminated by Robur’s design of a small, perforated cylinder inside the teapot, which contained the leaves for removal once the tea was ready to serve. This allowed tea to be kept warm in the pot without stewing, while also allowing the tea to be poured without depositing tea leaves in the cup. In a very clever marketing strategy, the company also printed ‘tickets’ on their packaged tea which could be used towards the purchase of the teapot. The article below explains how this was done. It was a clever means of helping to make an article of silver plate that was otherwise quite an expensive purchase, appear more affordable, and it apparently worked well. The ‘Perfect Teapot’ was produced from 1927 until at least 2002, long after the Robur Tea Company itself had been taken over by Tetley. Of course, it was also intended to persuade customers to continue purchasing Robur tea rather than another brand. In Lena’s case this strategy did not apply, which is just as well, because the family remembers that she always drank Bushells tea!

In a farmhouse kitchen

There was a routine to life on Lena and Bill’s farm that began early, with tea. The kettle sat on the hob near the fire all night so that it could come to the boil quickly when needed in the morning. Both early risers, Lena served Bill his first cup of tea soon after dawn, along with two biscuits — generally a milk coffee biscuit and a milk arrowroot. She then set about building the fire in the wood stove to cook breakfast, while Bill began on the first outdoor tasks of the day. An hour or so later Bill came in for a cooked breakfast. This varied from day to day, but often comprised meat (sausages or chops), or bacon and eggs, with toast and tea. Both drank their tea with milk and sugar, always from patterned china cups and saucers.

Morning tea followed at about ten o’clock. Biscuits were served once again, but these were home-baked biscuits — cornflake biscuits, little chocolate biscuits with almonds, or rock cakes. Lena was a good baker and bought her supplies in bulk, since the farm was some 26 miles (42 km) out of town. Beside the pantry in her kitchen was a cupboard with two large bins, one for flour and one for sugar, refilled from supplies bought by the bag.

Lunch was served at about 1pm, timed to tune into an episode of Blue Hills on the radio. This was generally a cold meal, with cold meat of some sort, salad, bread and butter — and tea. Hot food was probably served in the winter. Hear Michelle Arrow discuss Blue Hills and its place in Australian popular culture.

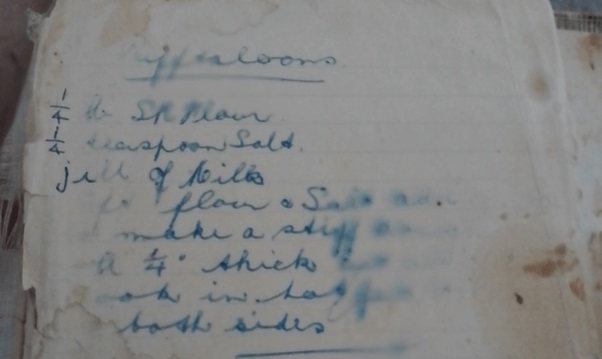

Work stopped again mid-afternoon for afternoon tea. This was a repeat of morning tea, but often cake replaced biscuits on the food menu. Lena’s recipe books are still preserved in the family and include recipes for a wide variety of cakes and biscuits. On special occasions there might be a sponge cake, (ginger was a favourite,) but one of the fondest family memories is of eating fresh pufftaloons hot from the pan. These used an old recipe originating with Lena’s first husband Henry Turner and dated from his time as a drover when he used to make these little cakes on a pan over a campfire. They were a cross between a scone and damper, a bit like Scots or Welsh griddle cakes without the sugar, and were also known as johnnycakes. Lena’s recipe is reproduced below. Like many such recipes, it is stained with use and has faded over time, so we repeat the ingredients and instructions here:

Lena Salau’s pufftaloons

¼ lb [pound] SR [self-raising] Flour

¼ teaspoon Salt

1 gill of Milk

Sift flour and salt, add milk, and make a stiff dough. Pat or roll dough until about ¼ inch thick [cut out rounds] and cook on a hot pan on both sides.

Lena always cooked her pufftaloons in butter. They were served straight from the pan, split and eaten buttered, or filled with jam and cream.

The final meal of the day was served after outside work ceased for the day and was generally called simply ‘tea’. This was almost always a hot meal, with a meat course and vegetables from the farm garden, followed by dessert. Lena’s grandchildren remember that dessert might be as simple as bread, jam and cream, since the farm kept a milch cow and separated their own cream to supply the house with both milk and cream. In the winter she made steamed puddings, and the recipe pages of these puddings are very worn. At some point they acquired a chest freezer, enabling Lena to keep ice cream. The chest freezer was also very helpful in freezing meat since Bill butchered his own mutton for home consumption. After the evening meal was cleared away the teapot came out once again for the last time to serve tea while the family played cards, listened to the radio, or later, watched TV. It sat, kept warm by its knitted tea cosy, until everyone was ready for bed. At that point it was rinsed and set aside ready for the morning.

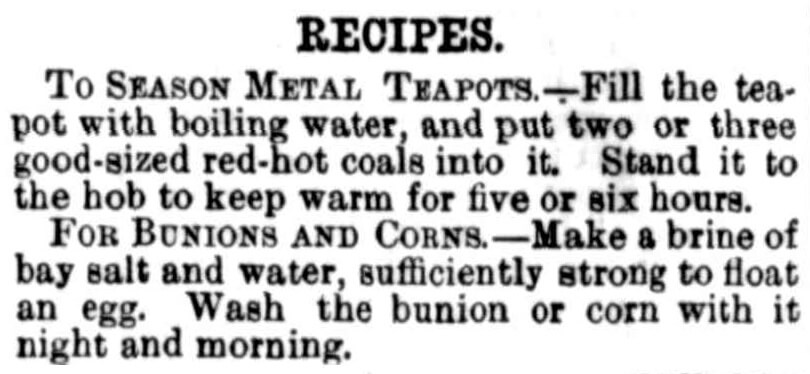

In line with popular tea lore, Lena’s grandchildren remember that the teapot was never washed inside, just rinsed out with water. Lena believed that the staining on the inside improved the flavour and that washing it would ‘spoil the flavour of the tea’. Against this belief, it must be said that there were also lots of directions for removing the accumulated tannin from inside teapots published in the newspapers, mostly by using ‘common salt’. (See e.g. Sunbury News, 14 January 1922, p1) It may be that the ban on cleaning was old lore that was changing in the twentieth century, although it certainly continues into the present. Or it may have been another of those tea beliefs that varied with the individual. Family members were undecided about whether the silver on the outside of the teapot was ever cleaned but do remember that it was tarnished from use. This long-held ban on cleaning the inside of a tea pot may help to explain a curious ‘recipe’ found in The Australasian on 19 June 1880 (p.7). Headed ‘To Season Metal Teapots’, it included the following directions:

Unfortunately, there was no explanation of what this was meant to achieve.

The schedule of meals remembered by Lena’s children and grandchildren seems to have varied very little from day to day. It allowed little rest for the busy housewife, but Lena was used to hard work and expected no less. Her own history had taught her that ‘life could be hard’ and she spared no time in complaining. The meals also suggest incidentally that the household consumed a large amount of sugar. In addition to the sugar added to tea, there were the biscuits, cakes, bread, and jam that accompanied it. We begin to see how Australians became the largest consumers of sugar!

Lena’s teapot (it was always known as ‘Granny’s teapot’ by the grandchildren) continued in use many times each day until Lena herself died in 1989. It was held in such affection by one of her granddaughters (Julie) that Lena promised her a similar Robur teapot when she married. This was duly presented on her marriage in 1983 and was used by another generation for many years. For all the children and grandchildren Lina’s silver teapot conjured happy memories of regular visits to Granny’s farmhouse kitchen, of meals around the large kitchen table, and copious cups of tea. Lena believed that family was of central importance and in her family, the tea ritual was an inextricable part of family life.