Gold! Gold! Gold! Gold!

Bright and yellow, hard and cold,

Molten, graven, hammer’d, and roll’d;

Heavy to get, and light to hold;

Hoarded, barter’d, bought, and sold,

Price of many a crime untold.

Gold! Gold! Gold! Gold!

-Thomas Hood (1799-1845)

The gold washed every day is dried, then dust and other light impurities are blown off, bits of iron are removed with a magnet, and the rest is minded by one of the miners until Saturday, when it is divided between partners.

- Seweryn Korzelinski, Memoirs of gold-digging in Australia, 1852-1856

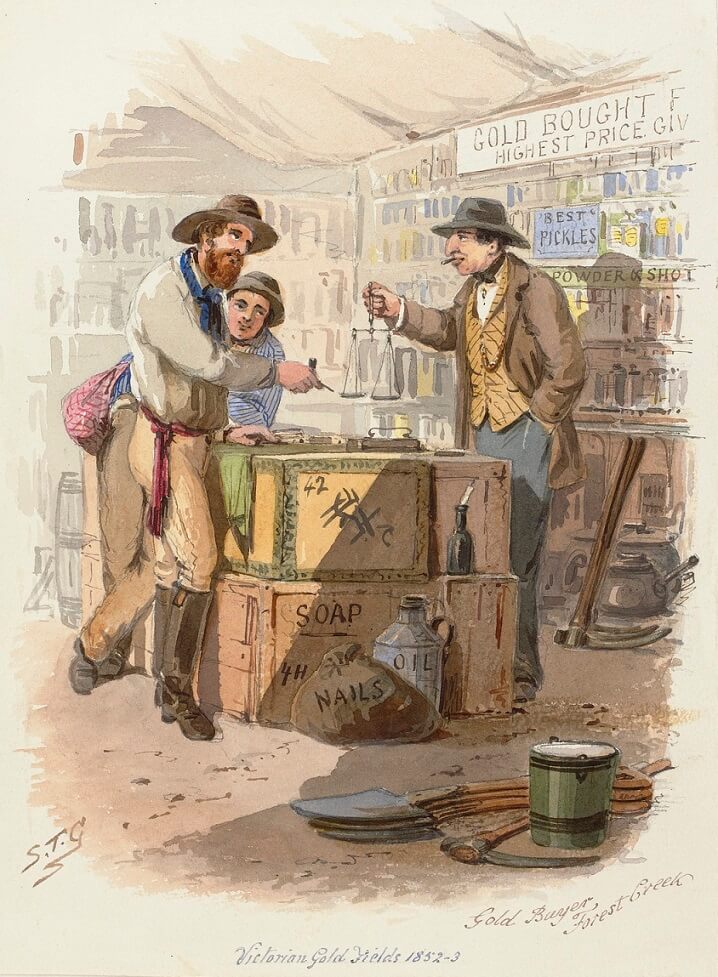

It is really most absurd to see rough, illiterate labourers come with their ounces and pounds of gold tied up in a bit of dirty rag … Most of them bring it in little round wooden matchboxes…

- Gold buyer at Mount Alexander, November 1851, cited in Murray’s Guide to the Gold Diggings, 1852

How did miners turn their gold dust, flakes and nuggets into usable money?

In the earliest days, diggers could sell their gold in stores on the goldfields. Storekeepers would weigh the gold and exchange it for goods or currency. There was no standard price, so the storekeepers set the rate. In Melbourne an ounce of gold fetched over £3 in 1852; at the diggings it sold for only £2 6s.

Tricks of the trade

Some shopkeepers could be unscrupulous and miners were warned about the many tricks used to cheat them. Some traders used faulty scales; others grew long fingernails under which they hid the gold flakes. Most miners preferred to get their gold back to Melbourne for sale, but this meant leaving the goldfields and days of work digging. It was also a dangerous journey. The preferred method was to pay to have their gold transported by armed escort.

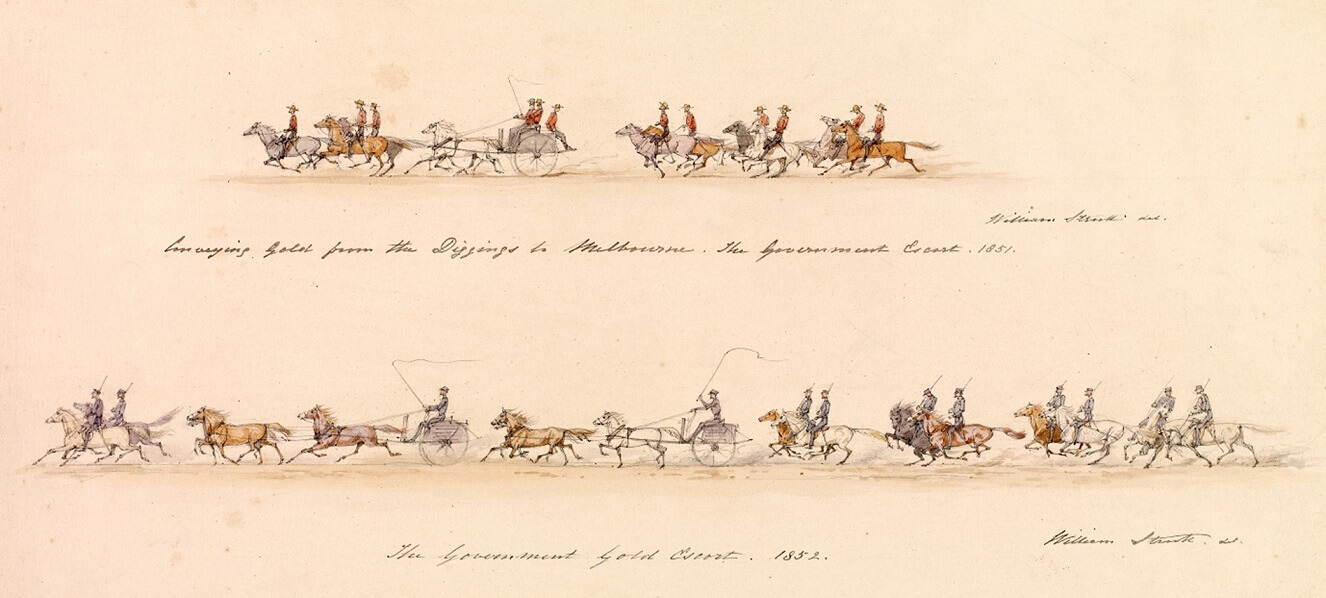

‘The Government Gold Escort’, by William Strutt, artist, 1852

Reproduced courtesy Victorian Parliamentary Library

A government-run escort service commenced in October 1851, departing the Ballarat diggings every Tuesday at 6am. For a small fee ― roughly sixpence per ounce ― the digger could send gold to support his family, or for safekeeping to his bank or the Colonial Treasury.

How did it work?

Miners took their gold to the Gold Commissioner’s camp, where it was weighed and bagged. A receipt was attached to the neck of the bag and a duplicate issued to the owner as proof of ownership. Gold could be collected from the Treasury in William Street between 10am-2pm Monday to Wednesday and Fridays; and Saturday 10am till noon. To reclaim his gold the digger produced a receipt and described the parcel: failure to do so saw the gold forfeited to the government.

What next?

The miner could sell his gold to a bank or private buyer or auction it for the highest price. Some had it processed into refined gold ingots (small bars). By July 1852 there were more than 200 gold buyers in Melbourne.

Almost all the gold (apart from that used at the Sydney Mint from 1855) was exported to Britain and France, where it was sold for coinage. What remained was quickly absorbed by industry for use as jewellery, goldleaf and plate, and in such trades as electrotype-processing and porcelain manufacture.

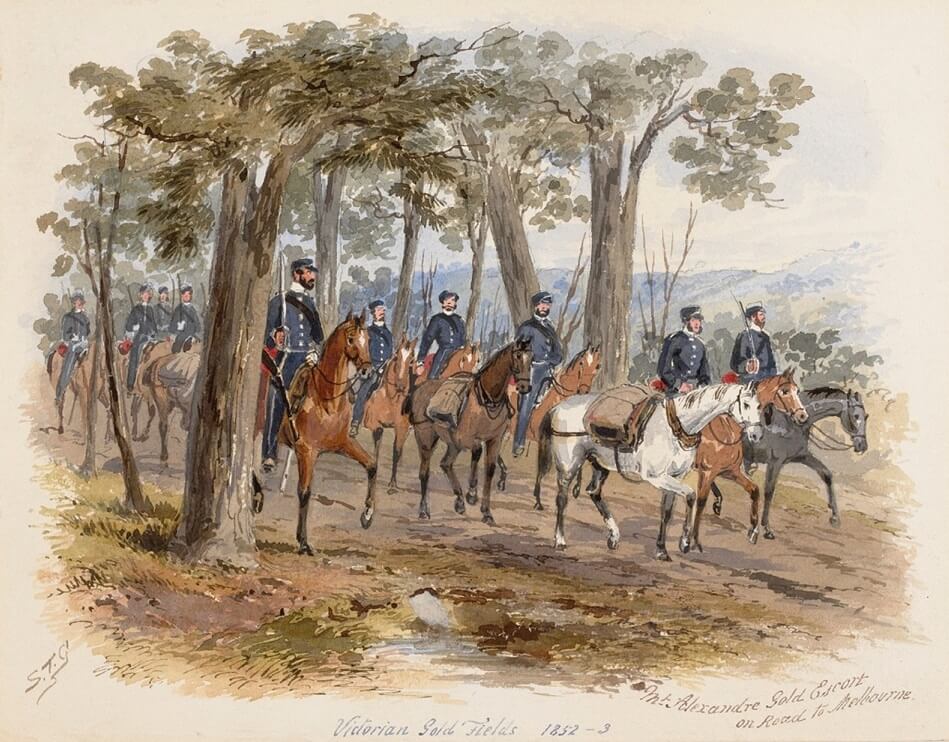

Mount Alexander gold escort on the road to Melbourne, by S.T. Gill, artist, 1852

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

The government escort service was unpopular amongst miners. Its gold-carts were slow, with no guarantee of safe delivery, or liability for loss. Private escort companies, such as the Melbourne and Mount Alexander Escort Company, commenced business in 1852. Unlike the government service, these companies guaranteed the safe passage of gold.

A Royal Mint opened in Sydney in May 1855 ― the first overseas branch of the Royal Mint, London. It processed raw gold into coins called ‘sovereigns’. It took about 8 grams of refined gold to make a sovereign, valued at £1. Sovereigns were quickly accepted in shops, banks, hotels and other businesses as payment for goods and services.

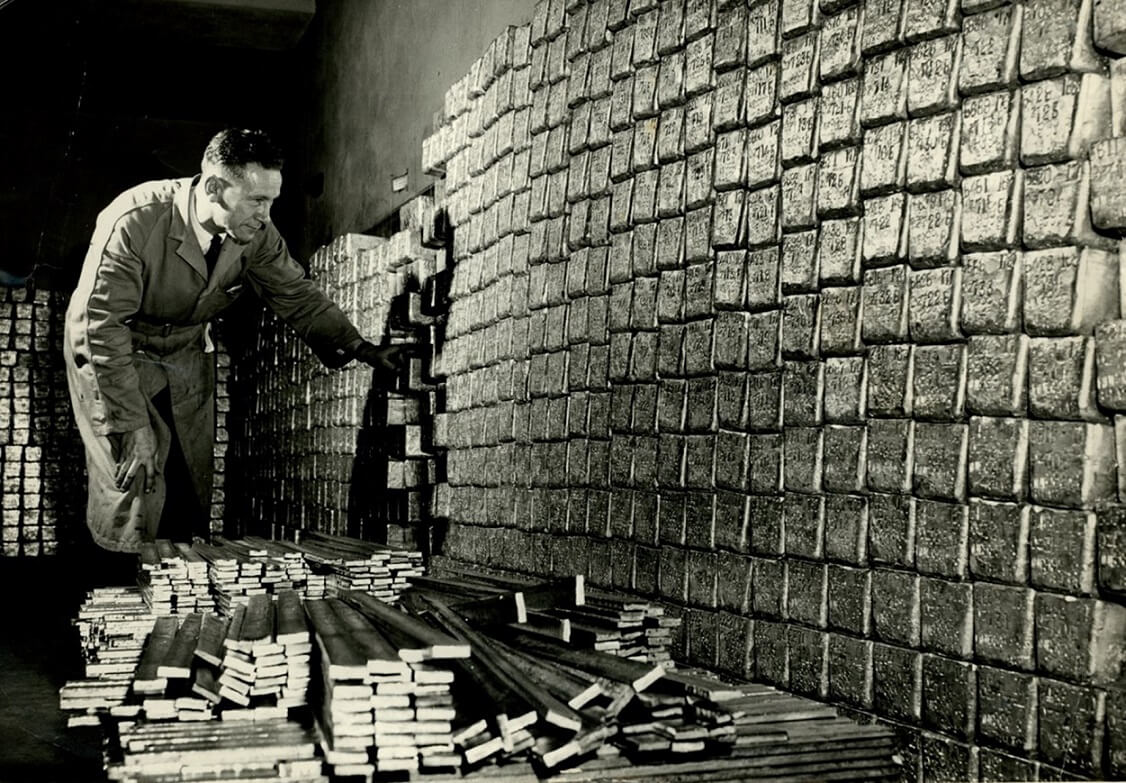

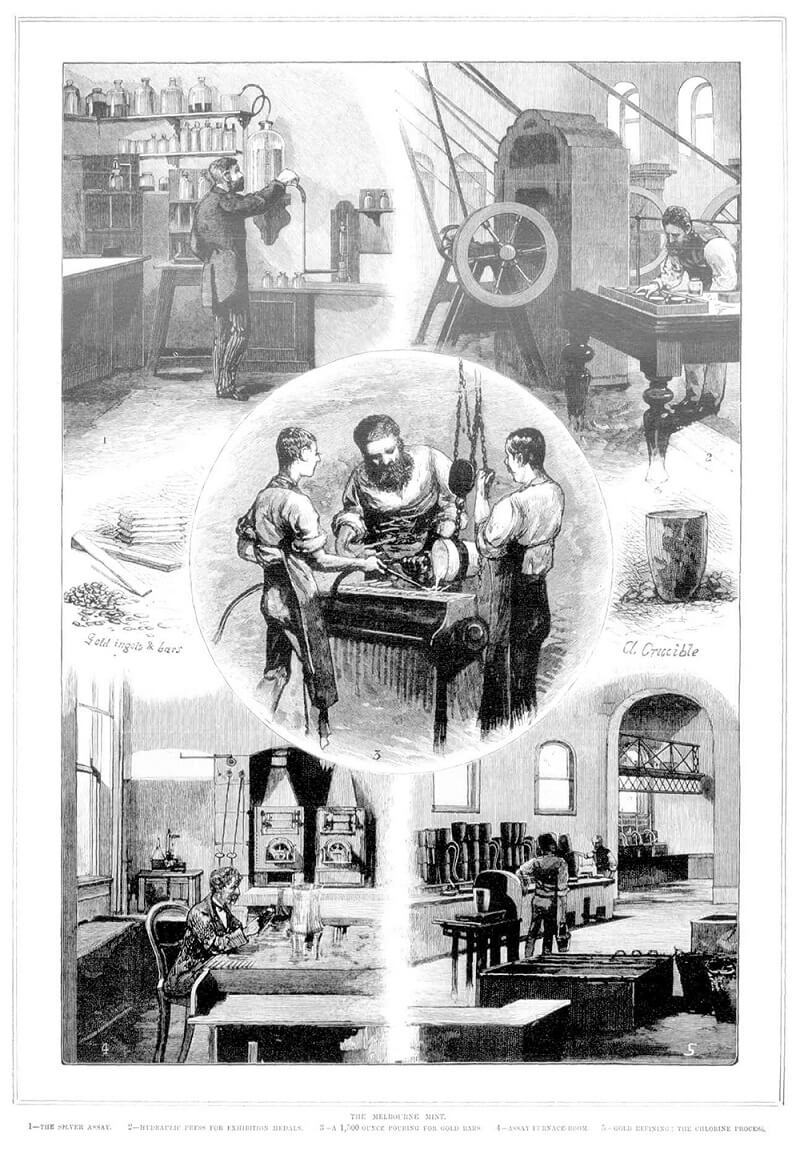

The Melbourne Branch of the Royal Mint opened for coinage in 1872. In the first 10 years, gold coins to the value of £15 million were minted. Refined gold was also cast into fine gold bars for export.

Stick ‘em up

Armed bandits occasionally robbed the gold escorts on their way to Melbourne. Known as ‘bushrangers’, these men (rarely women) were usually ex-convicts, escapees or failed gold-diggers. Some were cruel and cold-blooded: others were young and stole, not gold, but food and clothing to survive.

The police were little help. In fact, by the mid-1850s, most of the Melbourne City Police had deserted to the goldfields to try their luck.

The McIvor gold escort

In July 1853 the 'gold run' from McIvor was ambushed near Kyneton. Four men were wounded, and more than 2,000 ounces of gold was taken. Hundreds of miners set off in futile pursuit of the bushrangers. The Victorian police offered a reward and free pardon to any member of the gang who came forward. Two members did, leading to the capture of five of their fellow fugitives.

The Black Forest

The famed Black Forest, about 60 kms north-west of Melbourne, was feared by all travellers. As early as 1851 it had acquired the reputation of being ‘a dismal looking place, and one where a gang is most likely to resort to’. (The Argus, November 1851)

Black Forest was the haunt of notorious bushranger ‘Captain Melville’, who arrived in Victoria in 1851 after 15 years as a convict in Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). Subject to violent, uncontrollable rages, Melville sometimes showed a gallant side. In December 1852 he bailed up two diggers, robbed them of £37, then returned £10 to give them cash for Christmas.

Some suspicious characters lurk in the Black Forest near Kyneton, by George A. Kenyon, artist, c.1855

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Gold at the Old Treasury Building

Much of the interior of the old Treasury is similar to that of Government offices of the older type, but the building contains many odd corners of historical interest with which few but the caretaker Mr Herbert Patterson are familiar.

“Here”, said Mr. Patterson, pointing to a vault at the southern end of the building, fitted with double iron door, “is the place in which the gold was kept when the Treasury officers occupied the building. When I was a boy, more than 50 years ago, I remember seeing soldiers in the blue uniform of the 40th Regiment marching up and down the terraces guarding the gold in the vaults below. The red, wooden door in the south wall, just round the corner from Spring Street, was once the door of the guard house. I remember seeing the soldiers going in and out of the gloomy guardroom all day and all night.”

The Argus, 21 November 1931

We do not know how much gold was stored in the Old Treasury’s vaults: this information was rarely published. We can confirm that the Beechworth Escort delivered their gold to the Old Treasury from 1865, with some 300,000 ounces brought here.

When the building opened in 1862 gold could also be taken directly to the Customs Office for export, or to the numerous bank vaults in the city. From 1872 most gold went to the Royal Mint in Melbourne for processing into gold ingots and sovereigns. Find out more about this process at Museum Victoria.

Ovens and Murray Advertiser, 18 November 1865, pg 4

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

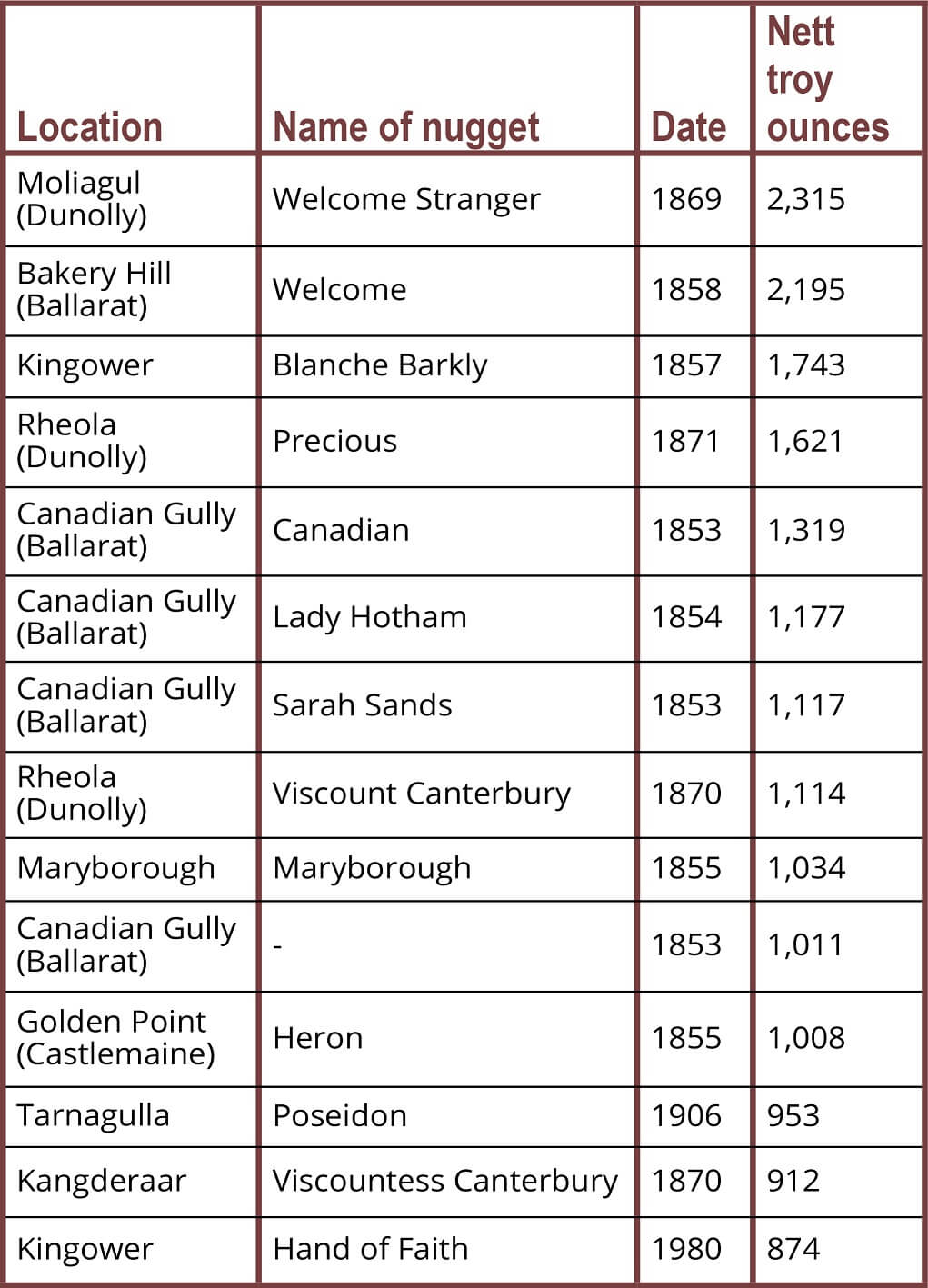

The Victorian gold nuggets were spectacular and unsurpassed. The ‘Welcome Stranger’ nugget, discovered on a bush track near Moliagul in 1869, remains today the largest alluvial gold nugget ever found in the world.

Nuggets – or rather, one big nugget – were what every digger dreamed of.

Few of the larger nuggets found in the first gold rush have survived intact. Most gold nuggets were sold and melted down, to minimise the chances of theft. Some of the smaller nuggets found their way to Europe, as gifts for royalty.

In recent times the metal detector has revolutionised the discovery of alluvial (surface) gold, and some lucky few have found sizeable nuggets. The ‘Hand of Faith’ nugget ― weighing a magnificent 27 kilograms (874 ounces) ― was found in Kingower in 1980 and sold to a Las Vegas casino for one million dollars. The 8 kilogram (256 ounces)’ Pride of Australia’ was discovered by two prospectors near Inglewood in 1981 and purchased by the State Bank of Victoria. It was stolen from the Museum of Victoria in 1991 and has never been recovered.

Exploration for gold continues to be an important activity for mining companies in Australia, with Australia one of the world’s largest producers of gold.

The lucky find!

The discovery of large nuggets aroused such excitement that news spread far and wide. It was, after all, equal to any modern lottery win.

At the sight of a ‘jeweller’s shop’ (large nugget) men reacted in various ways. Some were known to faint: others dropped to their knees to thank God. Most roared with delight and called out to their neighbours.

Some men banked their gains and returned to the fields. A few went back to Britain, their hopes fulfilled. But for others the new-found wealth was short-lived:

Johnston is said to have built a castle in Dandenong Road and to have been a working digger again a few years later. One Flanagan is said to have taken his £3,000 in sovereigns to a hotel, to have stripped off and rolled in them, and to have disposed of them within a week.

Geoffrey Serle, The Golden Age, p. 87

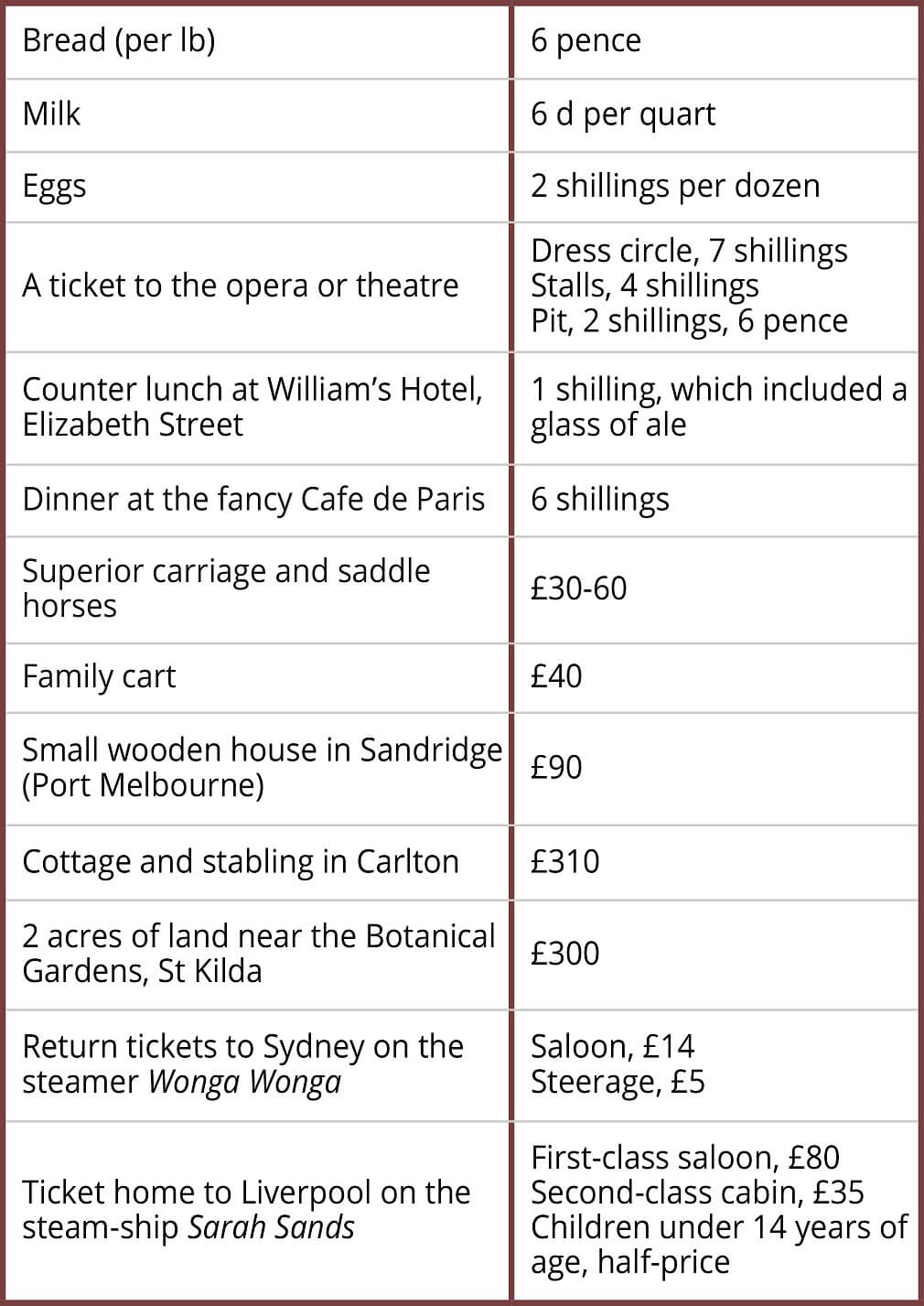

What could your gold buy in Gold Rush Melbourne?

1 lb = 0.45 kg

1 quart = 946 ml

12 pence (d) = 1 shilling (s)

20 shillings = 1 pound (£)

The allure of gold

Gold has been valued by nearly all societies over much of human history. And small wonder. It is shiny and beautiful. It does not rust, corrode or tarnish and it can be hammered into thin sheets (malleable) or drawn out into thin wires (ductile).

Above all, gold is extraordinarily rare. Copper is present in the earth’s crust at 55 parts per million (ppm) and iron at 56,000 ppm. Gold makes up less than 3 parts per billion of the Earth's outer layer. (Imagine 1 billion smarties in a bowl and only 3 of them are made of gold!)

Gold as currency

Gold has long been used as a medium of exchange or money. The first known use of gold in financial transactions dates back over 6,000 years. By the late-nineteenth century gold underwrote the world economy. The ‘gold standard’ was used to fix the value of money a bank could issue to the amount of gold it held in store. The idea was that currency issued (such as bank notes) represented a promise to pay the bearer in gold, so banks should hold enough to honour this promise.

Britain departed from the gold standard in 1931, and Australia followed suit in 1932. Banks were no longer required to retain gold reserves.

Gold’s value today

Gold is a highly conductive metal and is useful as a protective shield against heat and light. It is used in almost every sophisticated electronic device, from iPhones to smart TVs. Thin layers of gold are used as light filters in helmets for astronauts and the glass of aeroplane cockpits: it was even used as a coating on the Apollo 14 lunar module, the vehicle which first landed men on the moon.

Gold is also used in medical technologies, including dental fillings, stents, pacemakers and even targeted cancer medications.