Introduction

In the ten years from 1851, Melbourne more than quadrupled its population ― from 77,000 to 540,000, almost half the total population of Australia. Resident, Archibald Michie, wrote in 1860 that the small, ‘inferior English town’ had transformed into ‘a great city, as comfortable, as elegant, as luxurious as any place out of London or Paris.’

Public buildings were built on a grand scale, amongst them the impressive Parliament, Public Library, University, and Treasury. The cultural scene thrived, with internationally-renowned performers attracted by the prospect of large, affluent audiences. European-born artists and photographers sought out the colonial city and established successful studios.

The muddy city streets were flagged, kerbed and channeled, and harbingers of the modern age abounded. Gasworks provided gas to fuel the first city street lamps, piped water supply was installed, and new rail and telegraph services connected the city to country towns.

But beneath these signs of wealth and progress, Gold Rush Melbourne had its darker side. Tucked away in the narrow courts and lanes were the brothels and ‘disorderly houses’ of the city’s vice zone, and it was a brave person indeed who ventured down the meaner alleyways after dark. Life for the poor especially women and children, was particularly grim.

Henry Burn painted this view of Melbourne from Princes Bridge in 1862. At left is the just-completed Princes Bridge Hotel (today Young & Jackson’s). The twin-towered structure in the middle of the picture was St Paul’s School, opened in 1857. It adjoined St Paul’s Church, predecessor of today’s St Paul’s Cathedral. The square building in front of St Paul’s was the original City Morgue.

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

‘Collins Street’, by Francois Cogné, artist, 1864

Courtesy State Library Victoria

Collins Street became the city’s, and indeed the nation’s, ‘financial heart’. Just visible at the end of Collins Street is the elegant Treasury Building, built between 1858 and 1862.

Streets paved with gold?

The gold decade (1851-61) was a period of spectacular growth. Timber buildings in the city were rebuilt in solid stone and brick and work commenced on important public institutions ―the State Library and the University of Melbourne in 1854, Parliament House in 1856, and the Treasury Building in 1858. Houses were built for thousands of new immigrants and by 1853 large-scale subdivisions mushroomed in the city fringes. Better roads and the development of a rail network accelerated the suburban boom.

The suburban divide

The demand for housing sent land prices skyrocketing. The poor, displaced from the centre of the city by commercial and industrial development, clustered in tiny ‘gimcrack’ housing in Fitzroy, Collingwood and North Melbourne, while the wealthy built villas in Toorak, Hawthorn, and Kew. The ‘poor west vs affluent east’ pattern was established early.

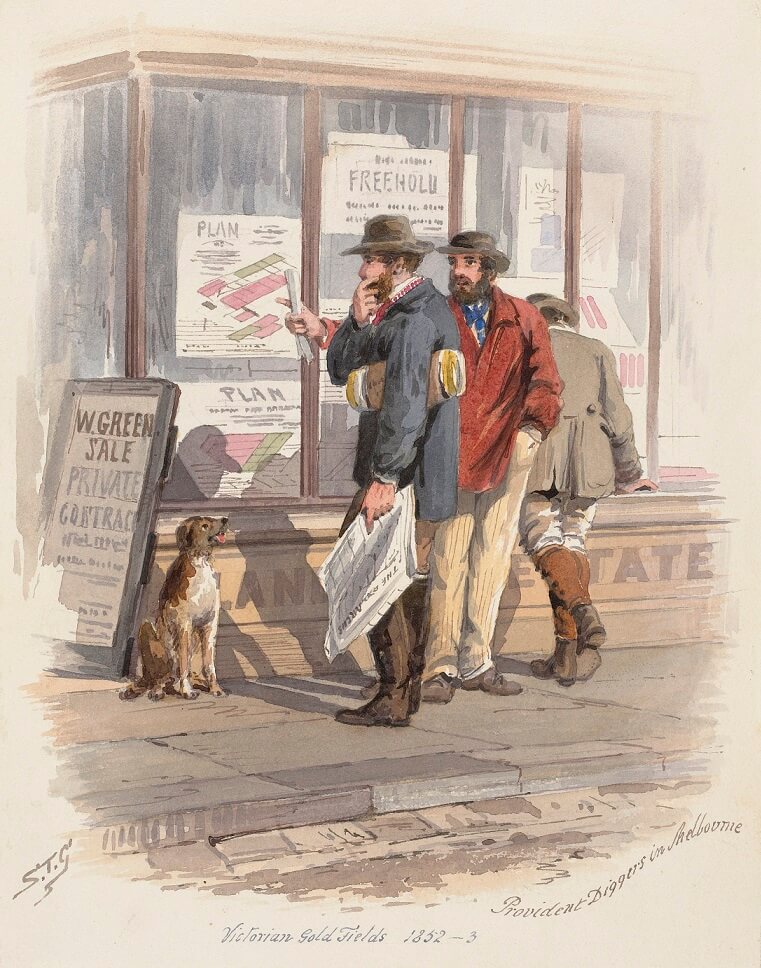

Provident diggers in Melbourne 1853, by S.T. Gill, artist, 1872

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Large numbers of subdivisional sales were held during the 1850s. Private owners, who had bought broad acres during earlier slumps, reaped large profits.

An ‘instant city’

Historian, Graeme Davison, describes Gold Rush Melbourne as an ‘instant’ city, with all the problems associated with rapid urban growth ― providing clean food and water, sufficient housing, help for the poor and public order.

Hygiene and sanitation were inadequate, undermining the city’s claims to greatness. Visitors complained of the filth that littered the city’s streets. There was no drainage or sewerage, and house blocks were often contaminated with sewage. City Inspectors found one yard covered ‘with twelve inches of green stagnant water’. Inside the dwelling, all five children were lying ill, some dying.

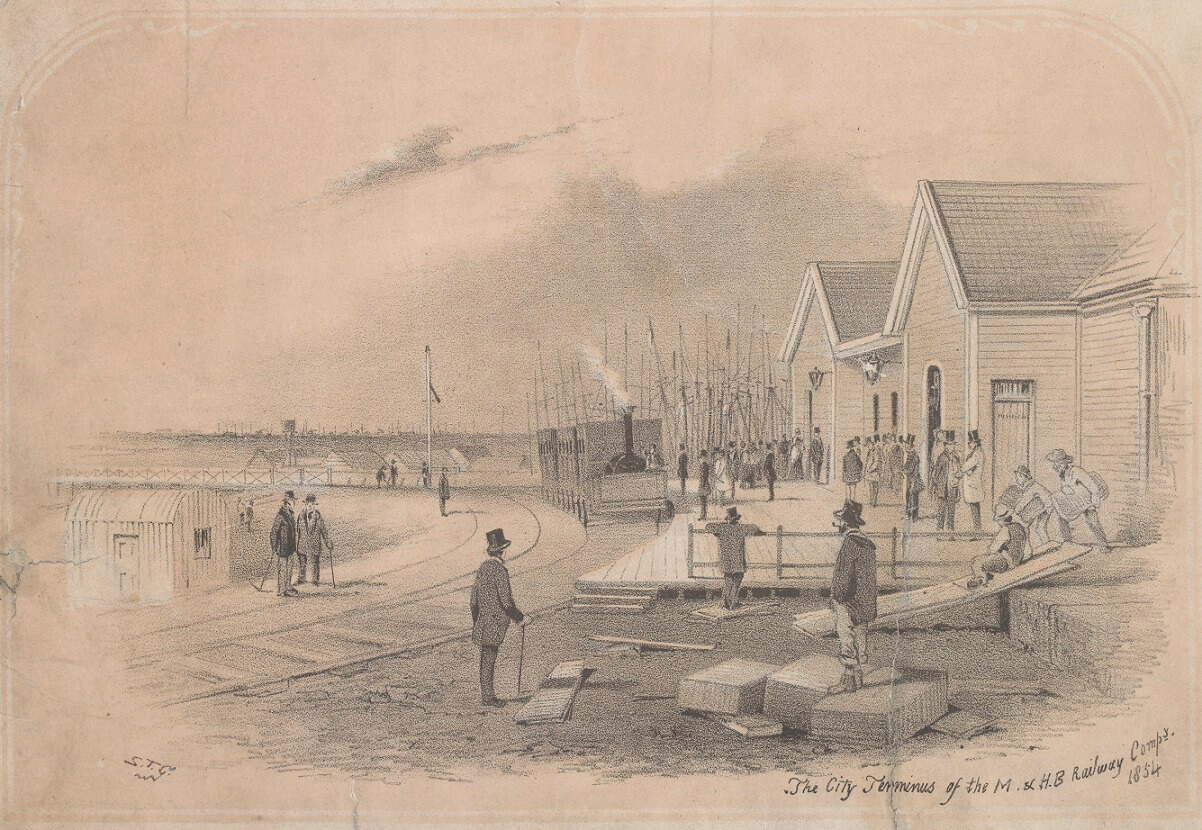

‘The City Terminus of the M. & H. B. Railway Compy. 1854’, by S. T. Gill, artist, 1854

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

The first railway line was built in 1854, linking the town centre and Sandridge (Port Melbourne). Other lines soon followed, linking the city and its fast-growing suburbs. Country areas, including Geelong and Ballarat, were among the first to be connected to the city, and in the 1860s a large central station at Spencer Street was built to service these routes.

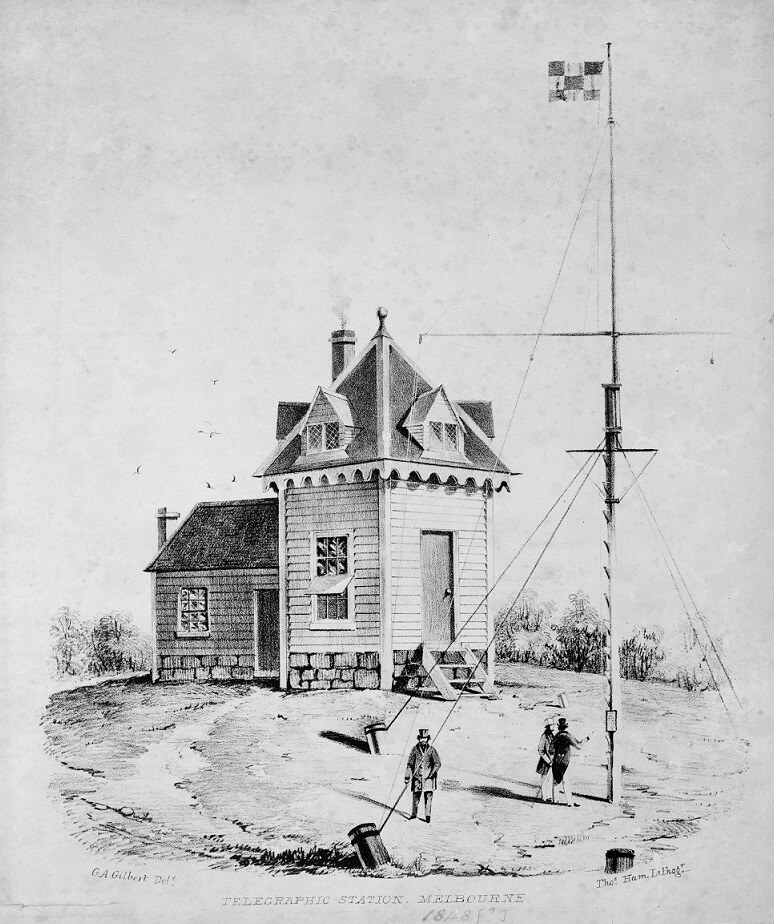

Telegraph Station, Melbourne, by Thomas Ham, lithographer, c.1854

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

It is hard to over-estimate the impact of the telegraph in a society accustomed to the leisurely pace of communication by letter. The telegraph, transmitting signals over an electric cable, offered what appeared to be almost instantaneous communication. News, business affairs and personal messages could be transmitted and answered in hours, not weeks.

The first telegraph line linked Melbourne and Williamstown in 1854 and by 1867 almost all Victorian towns were linked by telegraph.

‘The Public Library’, by Nicholas Chevalier, 1860

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

The Melbourne Public Library (now State Library Victoria) was established in 1853 by Lieutenant-Governor Charles Joseph La Trobe and Supreme Court judge Redmond Barry ― ‘one of a group of institutions intended to counteract the upheaval of the gold rush.’ The library was secular, democratic and enlightened, offering free access to self-improvement through learning, providing people had clean hands!

Melbourne Lying-In Hospital, by Charles Nettleton, c. 1868

Reproduced courtesy Medical History Museum, University of Melbourne (MHMA1309.1)

Medical care in the gold city was rudimentary at best. Most patients were treated at home by visiting doctors or were simply left to die. Paupers were sometimes admitted to Melbourne Hospital, the only public hospital, but demands for medical services in the early 1850s overwhelmed the hospital’s facilities. The death rate of patients was as high as one in four.

Women’s health services commenced in 1856 with the opening of the Lying-in Hospital, later the Royal Women's Hospital. Before this, poor women, widowed or deserted by partners, or pregnant out of wedlock, were largely excluded from access to care.

A commercial city

By the mid-1850s gold surpassed wool as Victoria’s chief export. Profits were channelled into public projects, and with private investment Melbourne became a thriving commercial centre.

Local manufacturing for building supplies ― lumber and bricks, in particular ― boomed as did agricultural production. Tens of thousands of acres were cleared for wheat, cereals, market gardens, and orchards.

With population growth came a new consumer market. Before the Gold Rush, 50 merchants operated in Melbourne: by the peak of the gold boom there were more than 300. This new merchant class challenged the previously-unrivalled power of the pastoral generation. As E. Carlton Booth recalled: ‘Every shopkeeper became a merchant and every merchant a prince’.

Bank of Victoria, Collins Street East, Melbourne, by Samuel Calvert, engraver, c.1863

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

A booming economy needed credit, and a place for savings. By 1860 eight of Australia's 15 trading banks were headquartered in Melbourne.

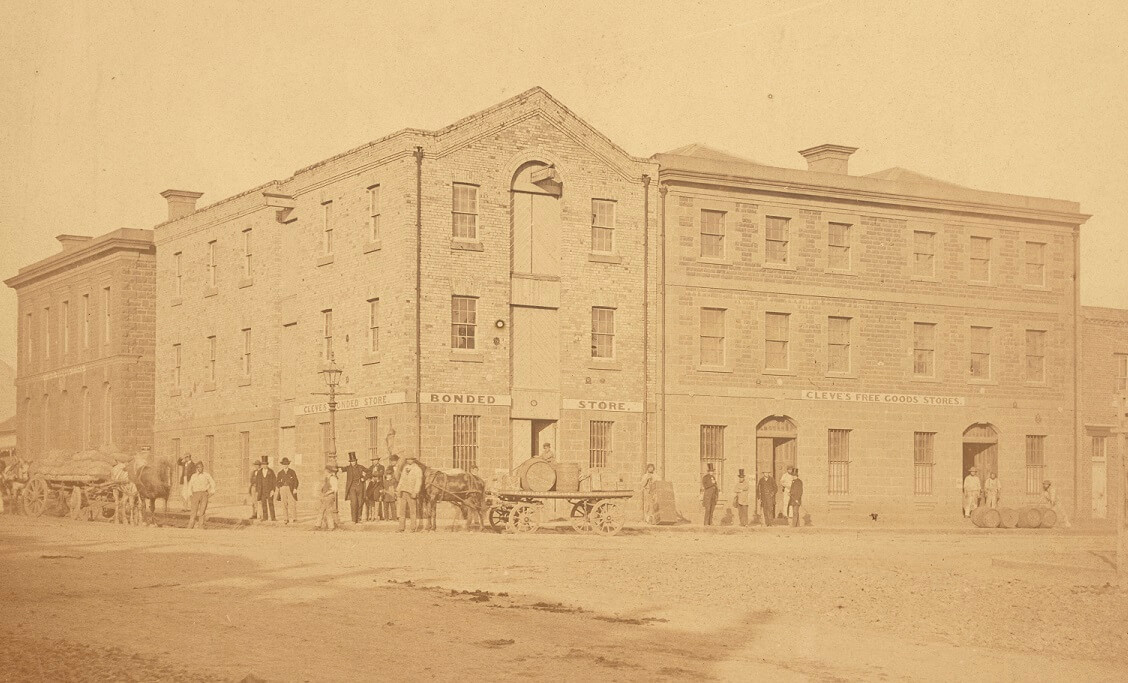

Warehouse on the corner of King and Lonsdale streets, by Cox and Luckin, photographer, 1861

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

New warehouses appeared near cargo discharge points on the Yarra River and railway termini. Most warehouses were built in bluestone, as security against thieves and fire.

Retail economy

Retail activity in the city settled into a pattern, one maintained to this day. Bourke Street became the preferred ‘strip’, while Collins Street had smaller, specialty stores. The first of Melbourne’s shopping arcades, Queen’s Arcade, opened in 1853.

Royal Arcade, by S. T. Gill, artist, c.1871

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

The Royal Arcade, the longest-standing arcade in Australia, opened in Bourke Street in 1870. This new style of shopping ‘centre’ used expensive city land efficiently and offered respite from the noise and grime of city streets.

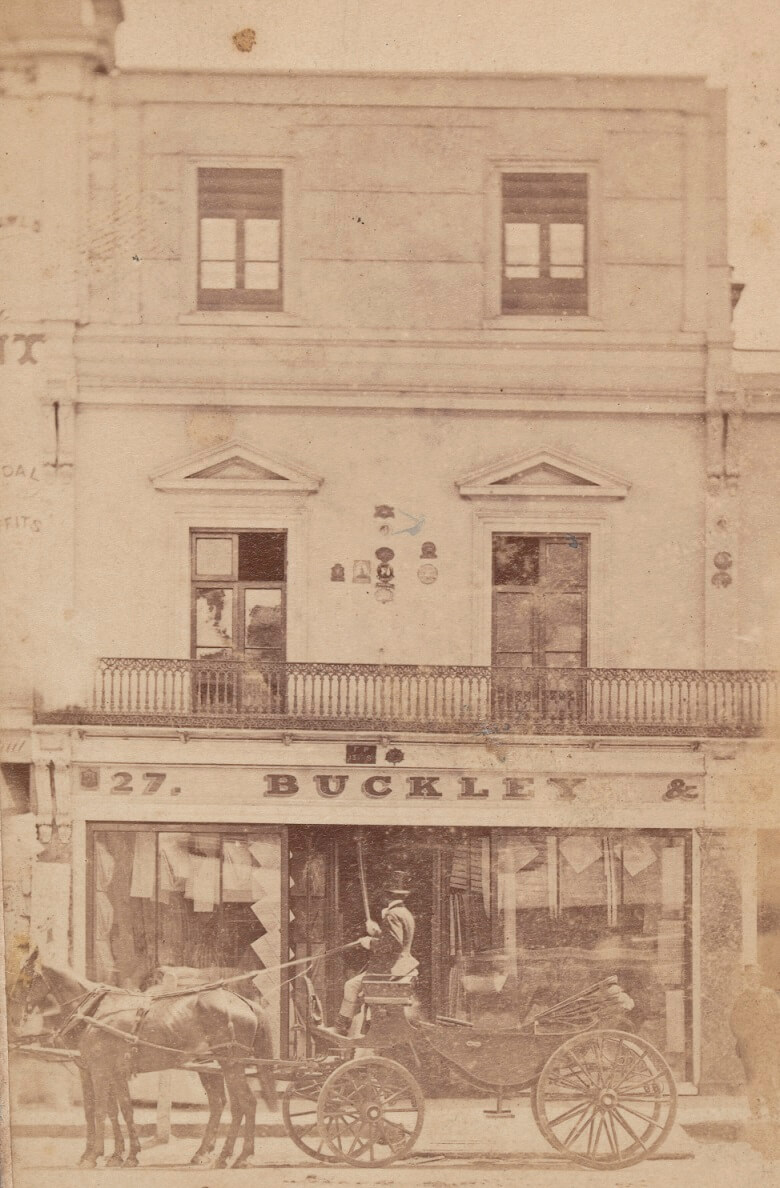

Buckley & Nunn, 27 Bourke Street East, Melbourne, by Davies & Co., photographer, c.1865

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Many families returned to Melbourne from the diggings and established businesses. Hundreds put their savings into small shops, becoming known as ‘the shopocracy of Melbourne’.

A typical shop in Gold Rush Melbourne had a small street frontage with the tenant and his family living upstairs. Opening hours were from early morning until late at night, six days a week, with the wife often taking charge.

The most successful of Gold Rush retailers was Irish-born Mars Buckley, who with his wife Elizabeth and partner C. J. Nunn, started a drapery business in Bourke Street in 1852. By 1861 the store was making an extraordinary £40,000 per year profit.

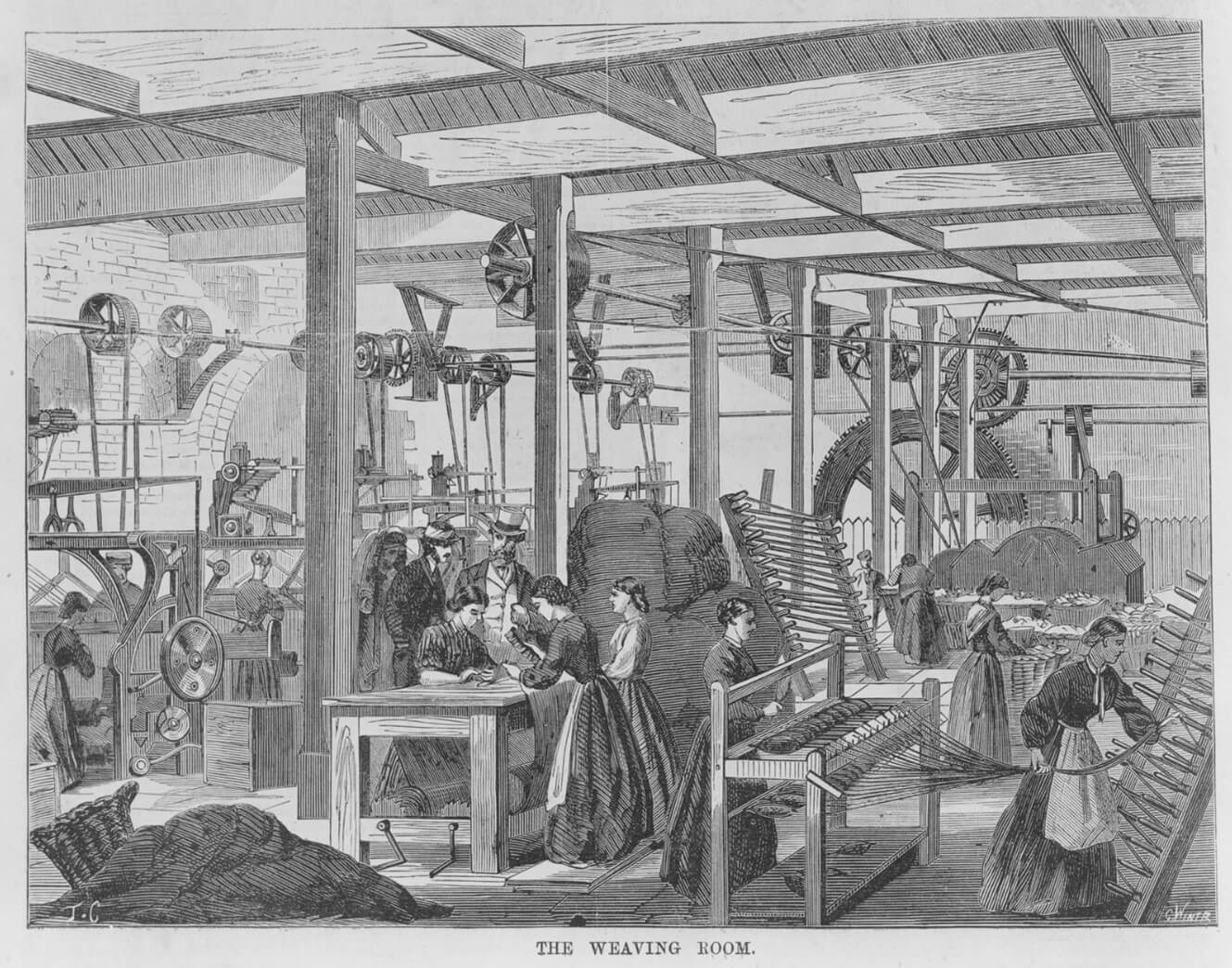

Working life

Merchant, William Westgarth, marveled in 1857: ‘Business is on a great scale, with great works of all kinds going on, and high wages to the labouring classes.’ Wages may have been high, but men laboured hard to earn them. No sickness entitlements were available or compensation for work-related death or injury.

Local manufacturing expanded, helped by protective tariffs. By 1871 more than 30 per cent of wage-earners worked in manufacturing. Factories and workshops lined the Yarra River and other waterways, their smells mingling with the stench of drains and untreated sewage.

A cultured city

Gold Rush Melbourne offered a dizzying array of entertainment, catering for every taste.

Bourke Street attracted the bachelor, with its brightly-lit bars, bowling alleys and billiard saloons. Promenading along Collins Street between Swanston and Elizabeth, or 'Doing the Block', became a favourite pastime of the wealthy.

There were excursions by railway to the beach at St Kilda, parks and gardens were created and sport as a spectacle emerged. Several new theatres were built, the most popular being George Coppin’s Theatre Royal, where stars such as the notorious Lola Montez performed.

Botanical Gardens by François Cogné, artist and lithographer, 1863

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

By the late 1850s some 300,000 people visited the Botanic Gardens each year. Ferdinand von Mueller, Director from 1857, aroused curiosity with his constant introduction of new plant species and an aviary.

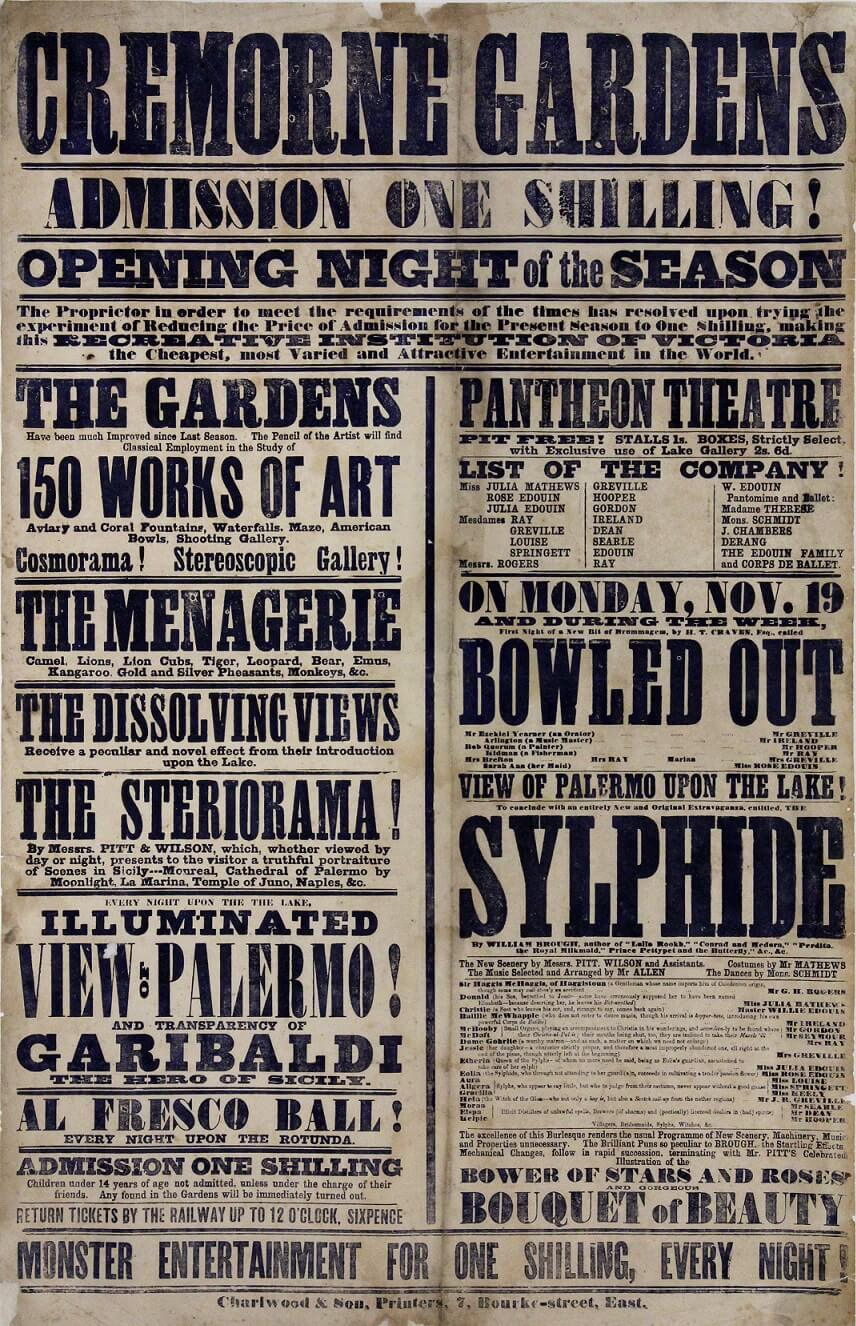

Cremorne Gardens broadsheet for the season 1860-61

Reproduced courtesy Performing Arts Collection, Arts Centre Melbourne

Some Gold Rush amusements were less restrained. At Cremorne Gardens, established in 1853, unmarried men and women socialised and danced late into the night ― much to the ire of moralists.

A sporting public

Melburnians’ passion for sport emerged in the gold decade. Richard Horne wrote of cricket in 1859: ‘The mania for bats and balls in the broiling sun during the last summer exceeded all rational excitements.’

Australian Rules Football also emerged in the 1850s. By 1859 it was codified. Teams, based on suburbs, gained members and ‘barrackers’ and a distinctly-Melbourne winter leisure pattern was established.

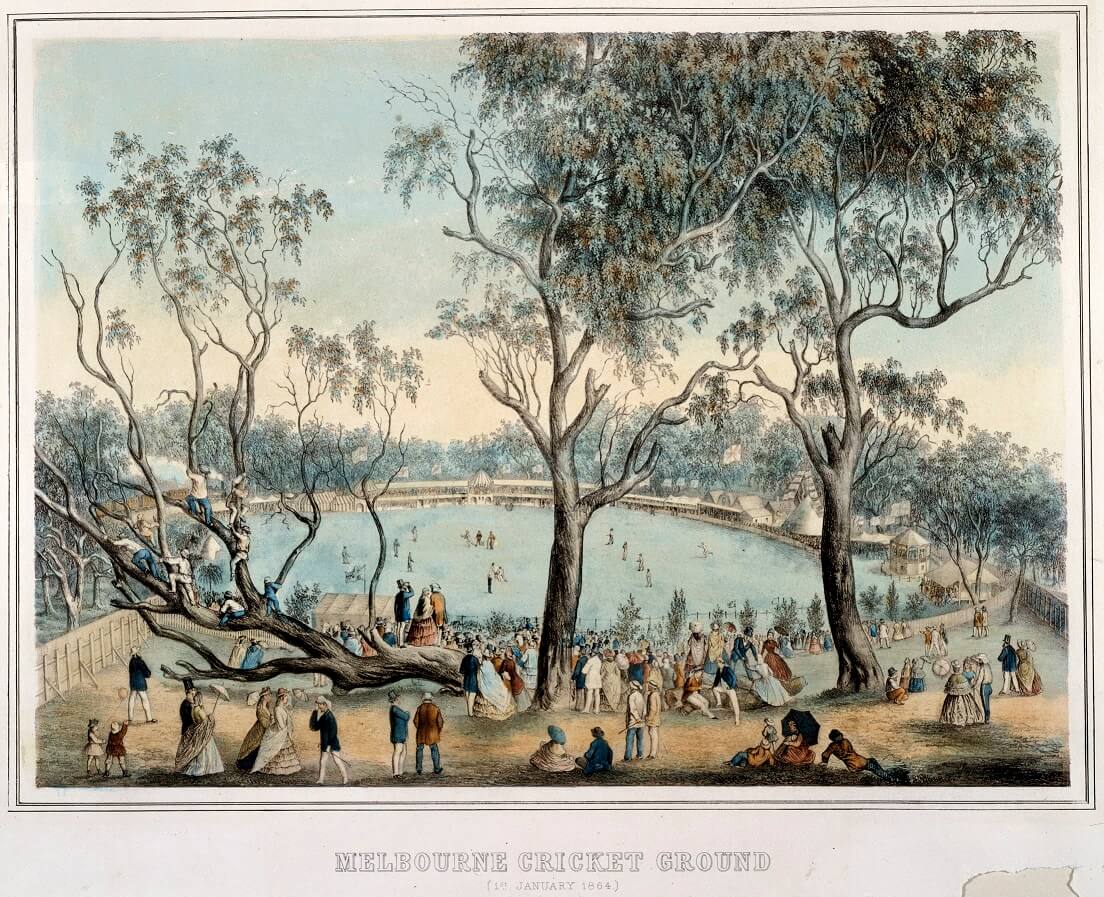

Melbourne Cricket Ground, published by Charles Troedel, 1864

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

The first English cricket team arrived in Melbourne in 1861. The long tradition of a series played between England and Australia for ‘The Ashes’ (of the first ball) began.

Arts and Culture

Increased wealth in the colony, and a growing middle class, also saw a market for colonial art. The influx of skilled artists like Eugene von Guerard, William Strutt and Nicholas Chevalier saw the growth of professional art societies, schools, and galleries.

Booksellers and publishers thrived and the increased circulation of daily newspapers, the Age, Argus and Australasian, expanded reading into people’s homes.

A City of Contrasts

The impact of the Gold Rush on the muddy village that was Melbourne was nothing less than spectacular. The city evolved into a structured society ― wealthy and open to significant political reforms. This period saw the introduction of the secret ballot, universal male suffrage and the eight-hour day for some lucky workers. Settlement was encouraged through changes to the land selection acts.

But the profits of gold were unevenly shared. Melbourne’s back-lane ‘slums’ presented a stark contrast to the city’s brash prosperity, while Victoria’s democratic reforms ignored the rights of women and First People.

‘Lucky Digger that returned’, by S.T. Gill, artist, 1869

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Artist S.T. Gill depicts a scene of family comfort, a successful digger surrounded by wife and child. Sadly, there were more unlucky than lucky diggers. Most who sought their fortune never found it and families suffered.

‘In Melbourne the extremes of wealth and poverty meet…’ – Ellen Clacy

A stone’s throw from fashionable Collins Street were the laneways of Little Lonsdale and Bourke streets, labelled in the 1860s as Melbourne’s slum district. Popular accounts painted these back streets as sinks of iniquity, a disreputable public ‘nuisance’. The public was both scandalised and fascinated by tales of overcrowded hovels, gambling dens, rampant prostitution and dirty, lice-ridden children. The Chinese that settled here struggled against racist jibes and overt discrimination.

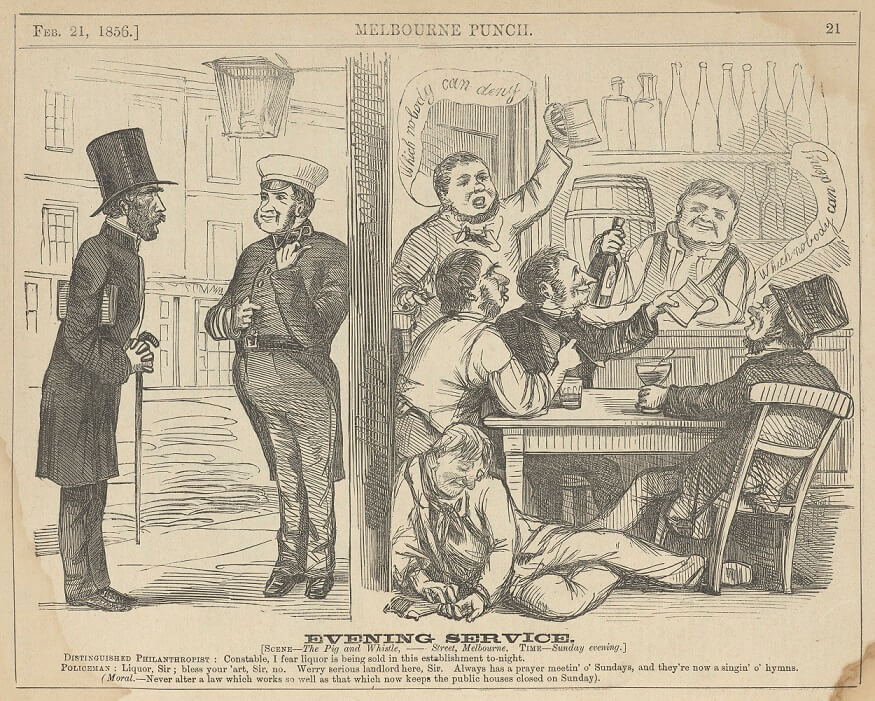

‘Evening Service’, Melbourne Punch, 21 February 1856

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Criminal activity flourished in the gold city, notably the sale of ‘sly grog’ (selling alcohol, mainly spirits, without a license). According to Lesley Moody, Chief Inspector of Distilleries, ‘every third lodging-house’ in Gold Rush Melbourne was a sly-grog shop.

Melbourne police were notorious for turning a blind eye. In this Melbourne Punch cartoon, a policeman tells a ‘distinguished philanthropist’ that the publican is holding his regular Sunday prayer meeting.

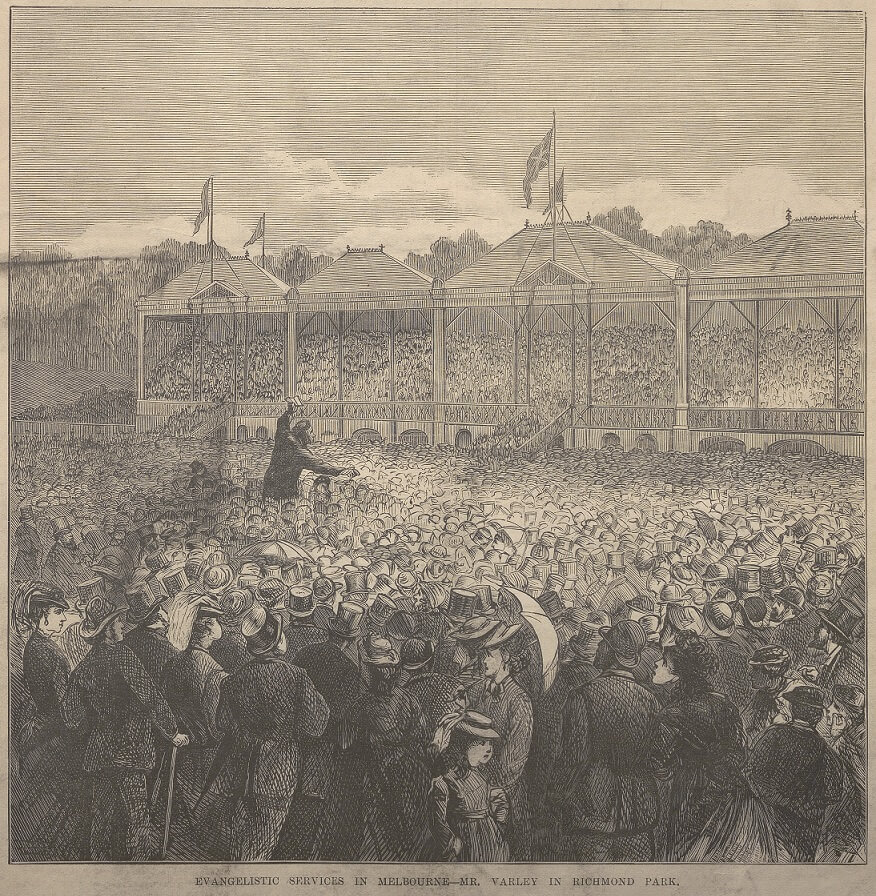

Visiting Baptist Henry Varley addresses large crowds in Richmond Park. Varley campaigned against Melbourne’s ‘social evil’ (i.e. ‘prostitution’).

Published in the Illustrated Australian News, by unknown artist, 3 October 1877

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Although not always classed as illegal, ‘prostitution’ was of great concern to moralists and social reformers, and they strove to eradicate it. Not surprisingly, they met with little success. Low female wages made it almost impossible for lone women to support themselves, let alone a family. For some the rewards of sex work outweighed its disadvantages.

Dirt, disease and destitution

The human costs of the Gold Rush were apparent in persistent outbreaks of typhus, cholera and dysentery. Children were most at risk: more than 80 per cent of Melbourne’s dead in 1853 were under 2 years of age. Sickness, death or desertion of the breadwinner pushed families into poverty and destitution. In desperation, abandoned wives and vagrant children sought the reluctant protection of the Benevolent Asylum in Flemington Road.

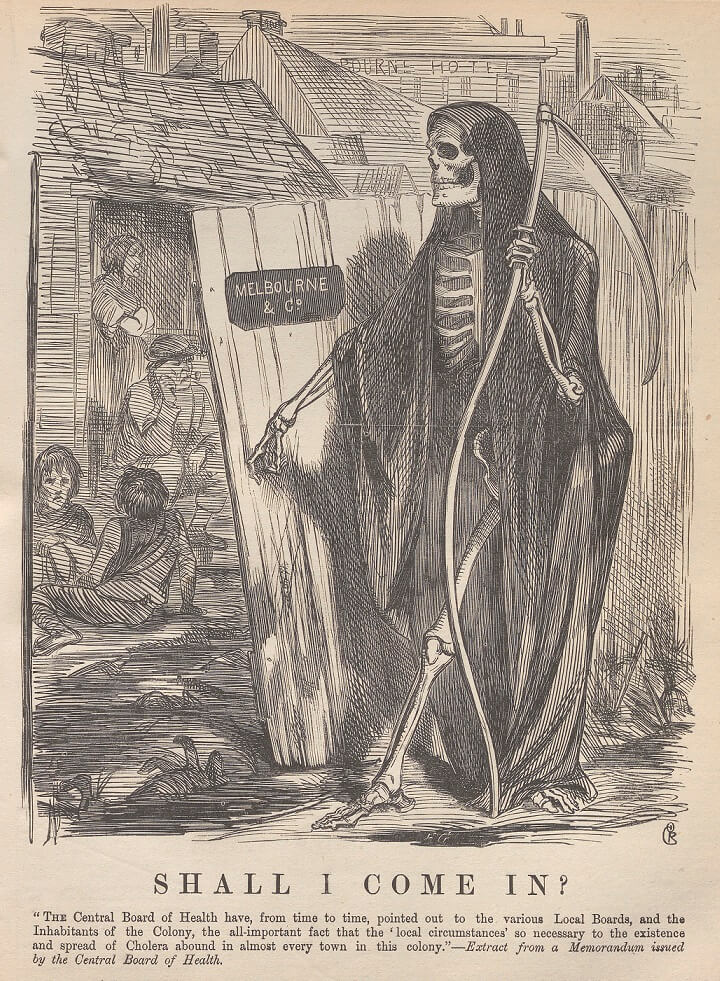

‘Shall I come in?’, by Oswald Rose Campbell, artist, Melbourne Punch, 4 October 1866

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

Prevailing theories of disease suggested deadly illness was spread by foul-smelling ‘bad air’. Melbourne’s backstreet ‘slums’, with their squalor and narrow laneways, aroused both fear and horror.

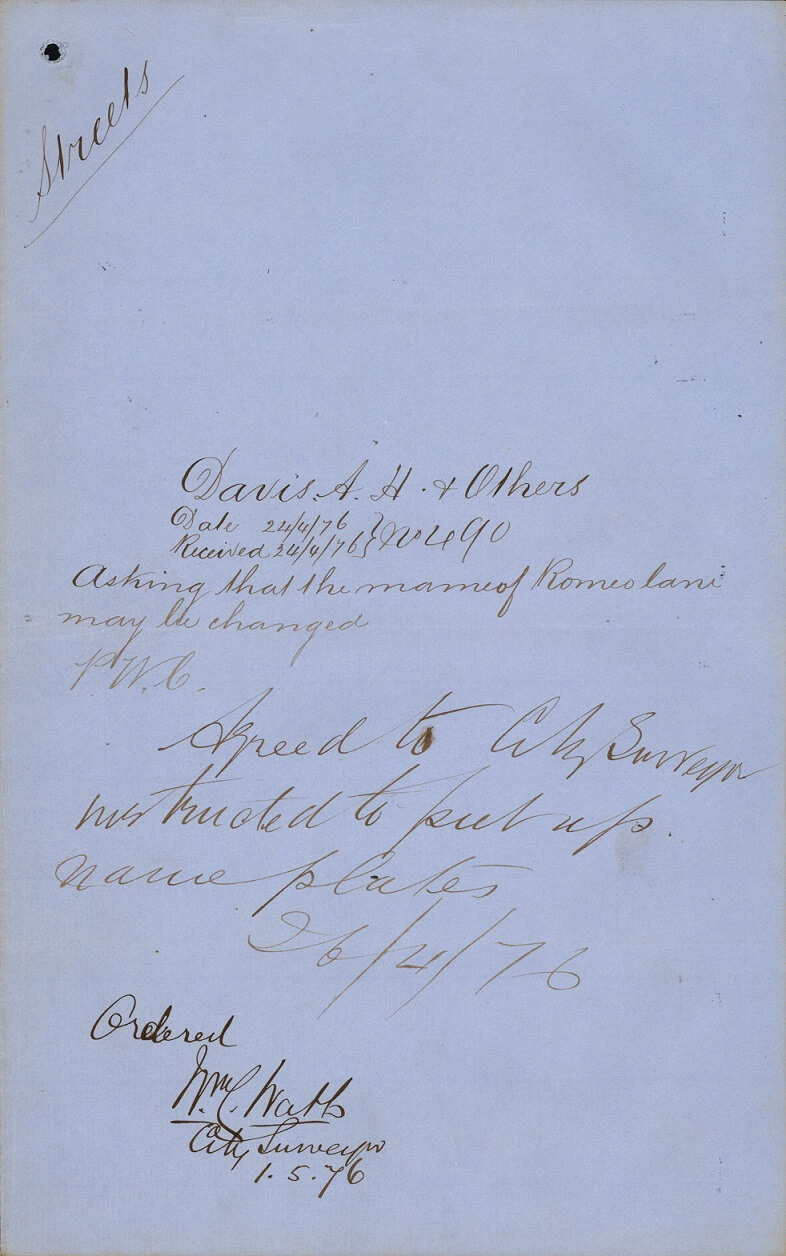

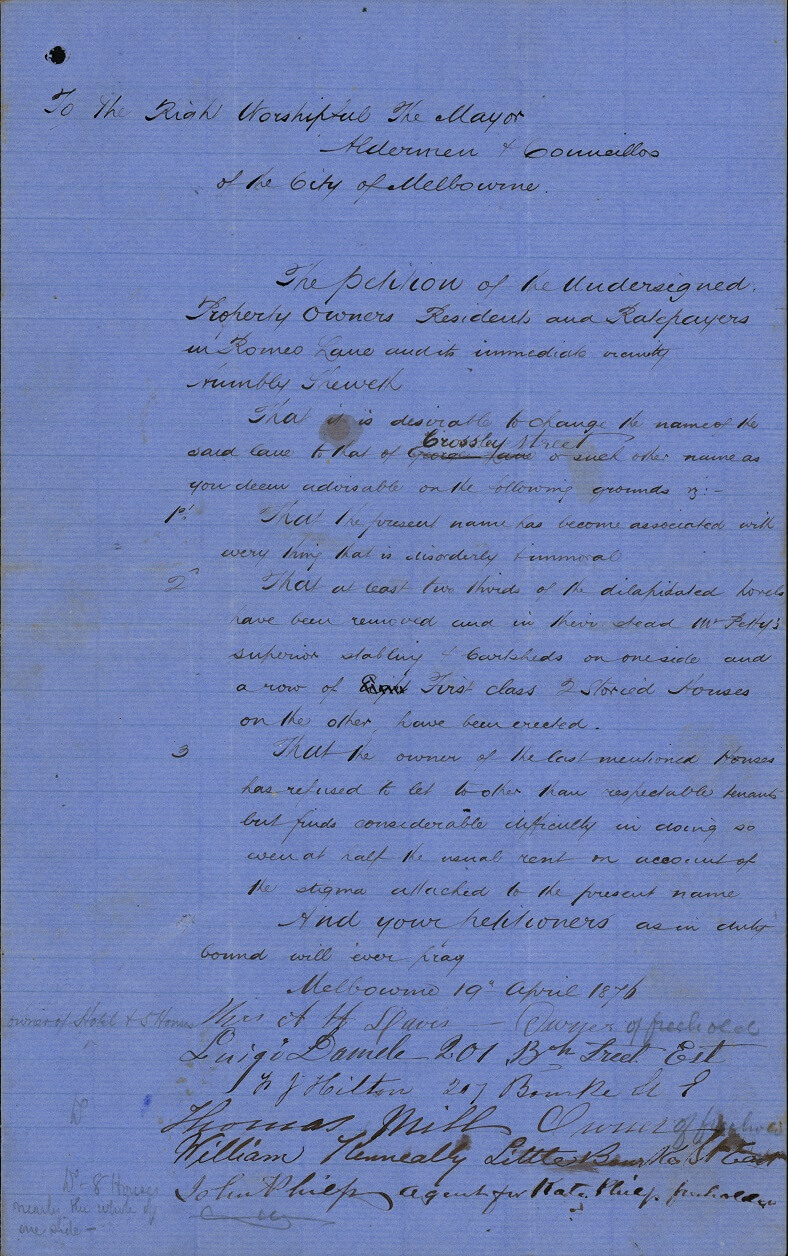

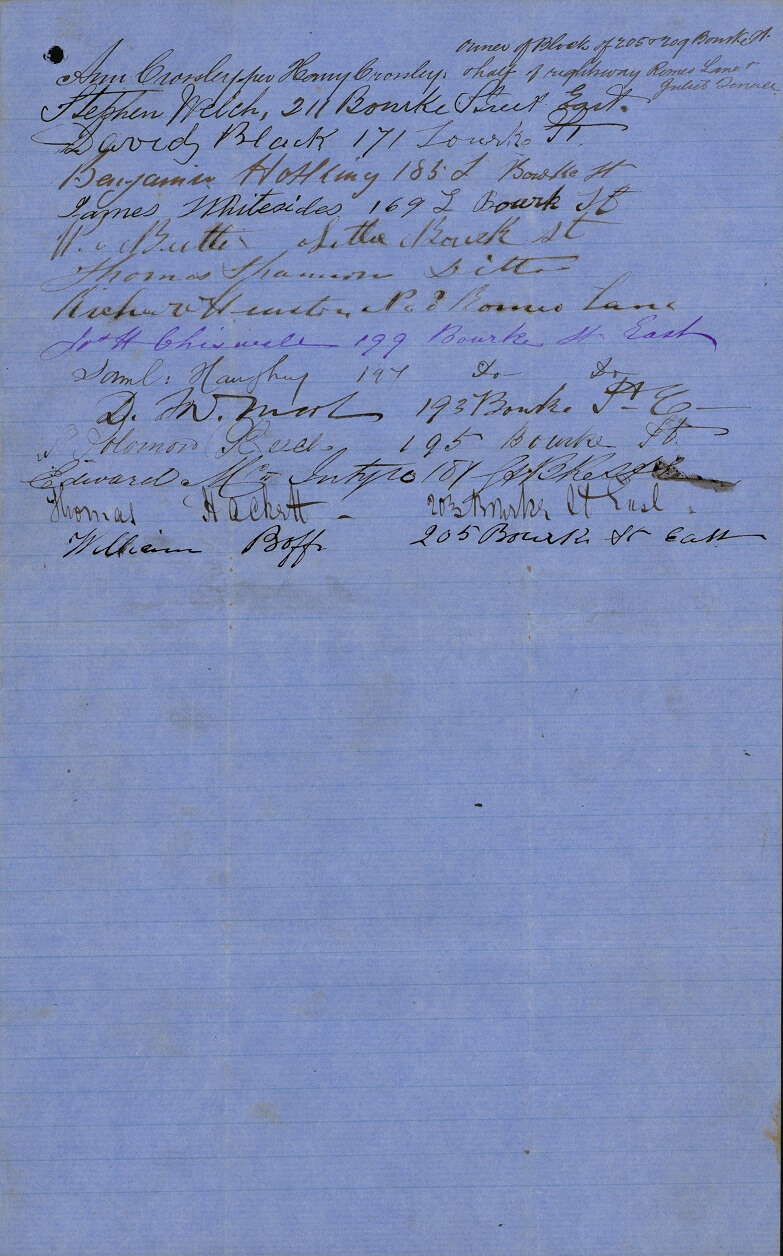

Petition of the ‘Property Owners, Residents and Ratepayers in Romeo Lane’, 24 April 1876

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria, VPRS 3181/P0, unit 834

In 1876 The Argus condemned the red-light alleys around Romeo Lane as ‘a plague spot to the city’, full of ‘hovels…vile haunts…thieves and bad characters’. In a bid to shake off its dubious reputation, residents successfully petitioned the Melbourne City Council in 1876 to change the name. Romeo Lane, with its 'disorderly' and 'immoral' associations, was changed to Crossley Street.

Isometrical plan of Melbourne, by de Gruchy & Leigh, lithographers, 1866

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

A plan of Melbourne showing the growth of suburbs such as East Melbourne, Collingwood and St Kilda to the south. Swampy land adjacent to the Botanic Gardens would later become Middle Park and Albert Park.

Collingwood, with more than 12,000 residents, was the most populous suburb in the 1860s. Local trades such as boot making, brewing, quarrying and brickmaking offered employment for the many unskilled and semi-skilled workers living in cheap, poorly-built houses. East Melbourne, with better-quality housing attracted middle-class residents, especially those from the medical profession ― a trend that continues today.

Prominent landmarks include St Patrick’s Cathedral, Parliament House, and the Treasury. Above this is the Richmond train and Melbourne Cricket Ground. Other features include the Melbourne Gaol, Public Library, Melbourne Hospital, and the Eastern Market. Spencer Street (now Southern Cross) Station can be seen on the far right.

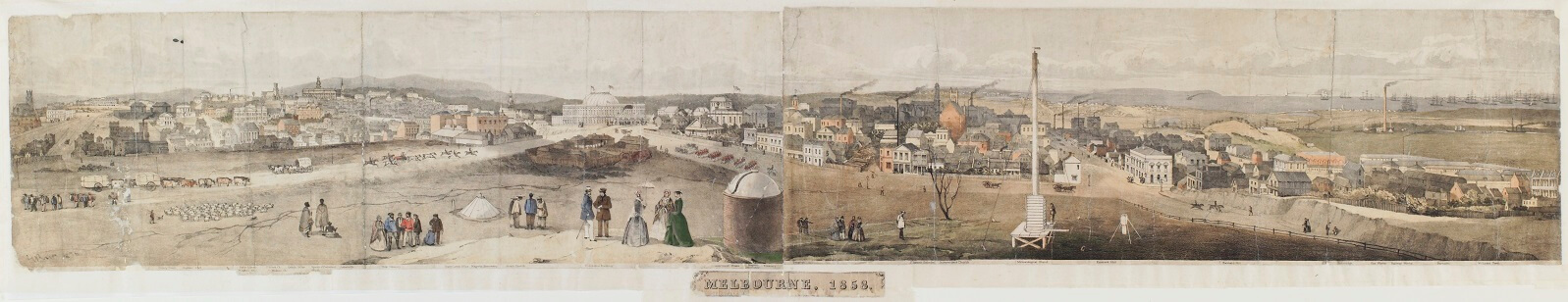

‘Melbourne from the Observatory’, by George Rowe, lithographer, 1858

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

George Rowe’s painting offers a different perspective of the gold city, looking from Flagstaff Hill in West Melbourne to the growing suburbs of East Melbourne and St Kilda.

Rowe includes landmarks like the 1854 Exhibition Building (demolished in the late 1860s), the Public Library (now State Library Victoria), Parliament House, the Police Barracks and the ‘New’ Treasury, as yet unbuilt. Centre stage is Professor Neumayer’s magnetic and meteorological observatory, which commenced observations in March 1858.

Flagstaff Hill was a popular meeting place, where the latest 'news from the Bay' could be had and fine views enjoyed. Ladies and gentlemen strolled, while others met in conversation. At the base of the hill Rowe depicts a shepherd tending to his flock, and bullock drays loaded with wool. A gold escort gallops along William Street, presumably towards the ‘Old’ Treasury.

The artist portrays a small group of First People on the hillside. For Traditional Owners the discovery of gold meant further incursions on Country. Some were forced to regather in and around Melbourne, despite colonial hostility. William Thomas, Guardian of Aborigines, reported in 1854 that the condition of First People had 'lamentably deteriorated’, and they were only 'with great difficulty kept from the town itself'.

Resources

Primary source material:

Public Record Office Victoria

State Library Victoria

Trove, National Library of Australia

Secondary source material:

David Goodman, Gold Seeking: Victoria and California in the 1850s, New South Wales, Allen & Unwin, 1994

David Hill, The Gold Rush, Sydney, Random House Australia, 2010

Don Garden, Victoria: A History, Melbourne, Thomas Nelson Australia, 1984

Geoffrey Serle, The Golden Age: A history of the colony of Victoria 1851-1861, Melbourne, Melbourne University Press, 1977

Graeme Davison, ‘Gold-Rush Melbourne’, in Iain McCalman, Alexander Cook and Andrew Reeves (eds), Gold: Forgotten Histories and Lost Objects of Australia, United Kingdom, Cambridge University Press, 2001

Helen Doyle, ‘Thematic History – A history of the City of Melbourne’s Urban Environment’, Melbourne, City of Melbourne, 2012

James Lesh, ‘Cremorne Gardens, Gold-Rush Melbourne, and the Victorian-era Pleasure Garden, 1853-63, Victorian Historical Journal, Volume 90, Number 2, December 2019

Margaret Anderson, ‘Mrs Charles Clacy, Lola Montez and Poll the Grogseller: Glimpses of Women on the Early Victorian Goldfields’, in Iain McCalman, Alexander Cook and Andrew Reeves (eds), Gold: Forgotten Histories and Lost Objects of Australia, United Kingdom, Cambridge University Press, 2001

Meg Mundell, ‘From hotbeds of depravity to hidden treasures: the narrative evolution of Melbourne’s Laneways, Text, Special Issue 55, April 2019, accessed online

Michael Cannon, Melbourne after the Gold Rush, Main Ridge, Victoria, Loch Haven Books, 1993

Shurlee Swain, ‘Mrs Hughes and the ‘Deserving Poor’, in Marilyn Lake and Farley Kelly (eds) Double Time: Women in Victoria – 150 Years Ringwood, Penguin, 1985

Weston Bate, Essential but Unplanned: The Story of Melbourne’s Lanes, Melbourne, The Griffin Press/State Library of Victoria, 1994