In May 1894 15 year-old Margaret Walters appeared before a coroner’s inquest in Drysdale near Geelong, charged with the murder of her new-born daughter. Murder was a capital crime at this time, with a mandatory death sentence, and Margaret’s plight was a pitiful one. Not only did she face the real possibility of conviction and execution, but the unwed pregnancy she had presumably hoped to keep hidden was about to be revealed in a very public way. For such trials were popular spectacles and most of the neighbourhood turned out to watch proceedings. The inquest and subsequent trial were also reported in detail in all of the colonial newspapers, including those in other colonies. There was no anonymity in reporting, and no protection of a child witness. Margaret’s shame was paraded for all to see and read about.

Sadly such stories were all-too common. Faced with the shame and burden of an illegitimate child many women and girls somehow managed to conceal their pregnancies, give birth in secret and abandon their babies undetected. Between 1885 and 1914 some 929 abandoned infants were recorded in Victoria: 614 were found dead and 315 alive. Almost certainly many hundreds more were never found. Reproductive crime has almost disappeared now, but it was a very common category of criminal charge for women in the past. This was the shameful back-story to the double sexual standard of the time.

Margaret’s story

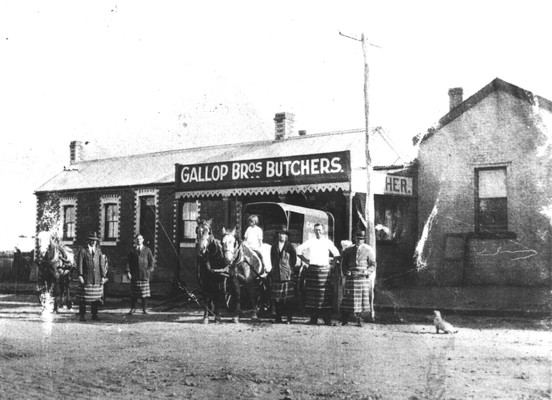

Margaret was aged just 15 years and five months when she faced the inquest. She had lived-in as a domestic servant in the household of the Gallops, local butchers in Drysdale, for some five months. That meant of course that Margaret was already four months’ pregnant when she joined the Gallop household. Somehow she managed to conceal her pregnancy (if indeed she even knew that she was pregnant) for many months, although household members later testified that they had noticed her ‘growing stouter’. Sometime in April Jane Gallop became suspicious. She told the court that ‘she questioned the girl as to her condition, when the prisoner positively denied that anything was wrong with her.’ Mrs Gallop was unconvinced and sent for Margaret’s mother, but after a three-way conversation, Jessie Walters also ‘said that there was nothing wrong with her.’ Nothing more was said, but on 24 April, while Margaret was assisting with the washing, Mrs Gallop noticed that she did not look well. When questioned, Margaret replied that she ‘only had a pain in her back’. In reality she was in the early stages of labour.

A lonely birth

Overnight on 25 April Margaret gave birth alone on her bedroom floor. The rest of the household heard nothing. She later told her mother that the baby ‘never stirred or cried after its birth’. She wrapped it in a pinafore and went back to bed, where she slept for a few hours. Just before dawn she crept from the house, dug a hole in the garden with a hoe and buried the body. Then she went about her usual duties ‘as if nothing had occurred.’

A gruesome discovery

Two days later the body was discovered. Another employee of Mr Gallop, a labourer named Henry Carver, gave evidence that he had noticed Margaret’s changed appearance, and also noticed a patch in the garden where the soil had been disturbed. Suspicious, he fetched a hoe and uncovered the baby’s body. He then alerted several others in the household and the police were called. The child had a major wound on the head and another on the arm, which was also dislocated. Initially Margaret denied that the child was hers, but a search of her room revealed blood stains on the floor and she was taken into custody. At the police station Margaret admitted to her mother, in the presence of the police constable, that she had indeed given birth and buried the child, believing it to be dead. She also named the father of her child as one Arthur Pidgeon.

Tried for murder

In Victoria at this time a woman who was suspected of killing her child was charged with murder. Under the Crimes Act 1890 (Vic) murder carried a mandatory death sentence, mitigated only by the Governor’s right to exercise mercy. Before 1894 no woman had actually been executed for killing her newborn child, although many had been convicted. Nevertheless the possibility was there, and such a trial was a terrifying ordeal for anyone, let alone a 15 year old girl. Although ‘only’ a coroner’s court, this was a trial by jury, with seven men sworn as jurors and with powers to reach a verdict of murder.

All hinged on whether there was any evidence that the child had lived and then whether, in the words of the coroner to the jury, ‘the mother afterwards wilfully and knowingly caused its death’. Margaret did not give evidence herself, and so all hinged on the opinion of the doctor who examined the baby’s body, and probably on the jurors’ perception of Margaret. Perhaps with this in mind, Constable Kirwin, who arrested Margaret, told the court that she ‘had lived at home [code for not running around the streets] and was of a very kind disposition. She was very fond of her brothers and sisters. She was always kind to animals’. The implication was that Margaret was a girl who was unlikely to have murdered her baby.

The medical evidence

The Geelong Advertiser reported on the proceedings at length and devoted considerable space to the medical evidence. This was presented by Dr Fred John Pacey, a local medical practitioner. His opinion was that the child had breathed, but he could not say categorically what had caused her death. He thought that the head wound would have been sufficient to cause death, but could not determine whether this wound was inflicted before or immediately after death. His evidence implied that medical science could not be definitive on that point. In answer to a question from Mr Whyte, representing Margaret, he agreed that the wounds might have been inflicted by the hoe in the process of burial. He also observed that the umbilical cord had been torn and not tied, but ruled that out as a cause of death. In his opinion the child might have died from being left unattended on the floor.

A ‘respectable’ family

Others to give evidence included Margaret’s mother, Mrs Jessie Walters. She was described as ‘a respectable looking woman and who was much affected at the position of her daughter, was accommodated with a chair during her evidence.’ Mrs Walters confirmed the account given by Mrs Gallop and also confirmed that her daughter had admitted to the birth in the lockup and to burying the child in the garden. She added that Margaret had said ‘that she did not think it had lived, as it never stirred or cried after its birth.’

The coroner’s summing up

In addressing the jury Mr W. Patterson, PM expressed the view that the jury had a ‘very difficult and delicate duty to perform, as this case is surrounded with mystery and very suspicious circumstances are connected with it’. Nevertheless he went on to remind the jury that it was their duty to consider only the evidence set before them, and ‘to erase from your minds all outside reports and rumors [sic] which may have reached your ears’. In determining whether the evidence suggested that the child had lived, he reminded them of their duty to bring in a finding of wilful murder, if they thought the evidence was convincing, ‘irrespective altogether of any sympathy you may feel for the young mother in the unfortunate position in which she is placed’. However he went on to add that despite the fact that as a full-term child ‘the probabilities are it should have lived, there is certainly no positive evidence that it did so.’

The verdict

After a short retirement the jury returned a unanimous verdict that the ‘child was found dead, and that there was no evidence to show how it met its death’. Margaret was then formally acquitted, but immediately charged with concealment of birth. This was an automatic charge in matters of this kind. A special Court of Petty Sessions was convened immediately, the evidence was re-stated and Margaret entered a plea of guilty. She also gave evidence to this court, repeating that the child was hers. Her evidence was reported in summary:

The child had never moved or cried after it had been given birth to. She did not hit it with any instrument, neither did she strike it with the hoe. If it was struck at all, it was when it was being covered over.’ [i]

Margaret was then remanded for trial at the Geelong Supreme Court on a charge of concealment of birth. Bail was posted at £25 with a surety of £50, but ‘as bail was not forthcoming’ she was sent to the Geelong Gaol hospital to await her trial.

Geelong Supreme Court - ‘more sinned against than sinning’

Margaret appeared before Justice Hodges in the Geelong Supreme Court on 15 May on the charge of concealment of birth. She entered a plea of guilty and was remanded for sentencing while Justice Hodges read through the depositions. On this occasion His Honour was minded to be merciful. In addressing Margaret he was reported as saying that:

He had not to punish her for being a mother without being a wife. With that he had nothing to do, but simply to administer the law as he found it. She was probably more sinned against than sinning, and being very young had not properly apprehended the fact that the concealment of the birth of her child was a crime…Under the circumstances the case would be met by a light punishment, and he therefore directed that a sentence of three months’ imprisonment should be recorded against her, the sentence to be suspended upon her entering into a surety of £10 to be of good behaviour for 12 months. He sincerely hoped that the girl would profit by the painful position in which she then found herself, and that she would not appear in court again.[ii]

The bond was ‘entered into’ and Margaret left the court with her mother.

Postscript

In 1891 the age of consent increased from 12 to 16 years for girls in Victoria. This meant that Margaret was well under the age of consent when she became pregnant and the authorities immediately determined to charge the man responsible. Margaret had identified Arthur Joseph Pidgeon as the father of her child and the police soon arrested him in Nhill on a carnal knowledge charge. He appeared in the Drysdale Police Court on 22 May. Pidgeon immediately agreed to marry Margaret and it was reported that she ‘consented to become his wife’, despite her age.[iii] The case was adjourned to allow the marriage to take place. Pidgeon was back in court on 29 May to show evidence that the marriage had indeed taken place and police then dropped the charge against him.[iv] Although newspaper reports had described Arthur Pidgeon as a ‘youth’, he was in fact a man of 26 when he married Margaret.

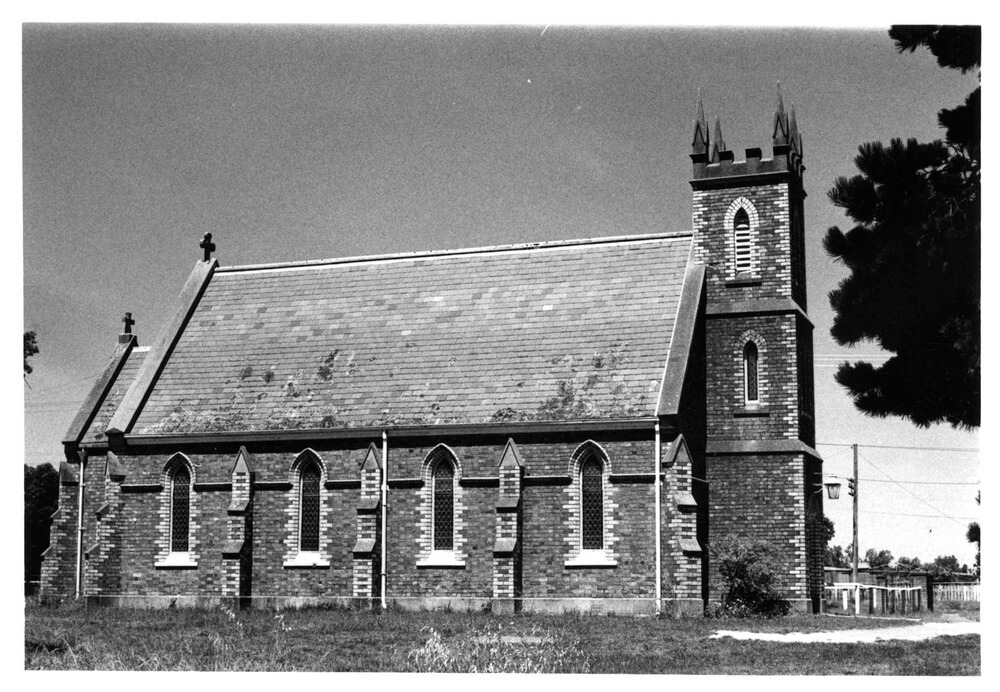

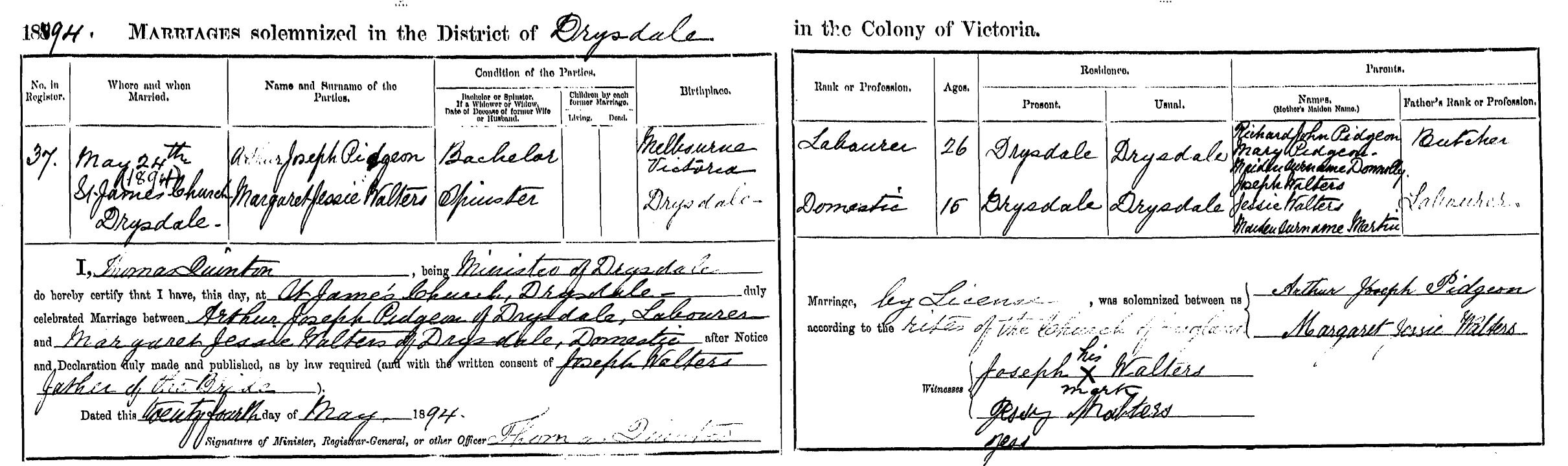

Other information can be gleaned from the marriage record of Margaret and Arthur, provided here by courtesy of the Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages Victoria. It confirms that they married in St James Church Drysdale on 24 May 1894. Arthur's occupation was given as 'labourer' and Margaret's as 'domestic', although it is interesting that Arthur's father was also a butcher. Both signed the register. Witnesses to the marriage were Margaret's parents, Joseph and Jessie Walters. Although Jessie signed her name, Joseph made his mark. Joseph's consent to the marriage was also recorded, given Margaret's age. His occupation was listed as 'labourer'.

Presumably this was seen as a satisfactory resolution of the matter by all concerned - the police, the courts, Margaret’s parents and the parties themselves, although we have no way of knowing what Margaret and Arthur really thought. Perhaps they were genuinely fond of each other. On the other hand, Arthur faced a prison term of at least three years if convicted on a carnal knowledge charge, so his motivation for marriage is obvious. Margaret may well have decided that it was better for her to be married too, since her reputation was decidedly compromised. We can only hope that they managed to put the experience behind them.

Margaret went on to bear another nine children over the following 23 years – the first in May 1895 and the last in May 1917. Their children in order were: Ethel May, born 29 May 1895; Elizabeth, born 17 November 1896; Nellie, born 1898; Sarah Georgina, born 1900; Arthur Joseph, born 2 September 1903; Margaret Jessie, born 1907; Richard John, born 1909; William Francis, born 18 February 1912 and Ruby Mavis, born 13 May 1917. By the time she was 20, Margaret had given birth to four children, three of whom were still living. Her's was a very traditional childbearing pattern and she had a larger family than the average at that time - perhaps partly because she started so young. Whatever family limitation she and Arthur might have attempted, was not very reliable. For those who like to note coincidences, we also point out that May was an oddly significant month in the lives of both Margaret and Arthur. Margaret's trial was in May, they married in May, their first and last children were born in May, Arthur died in May 1920 his age listed as 55 (he was likely closer to 52) and Margaret in May 1934, at the age of 55. Arthur’s death was reported briefly in the Geelong Advertiser. He was described as the father of a ‘grown family’ (although their youngest at that point was only three years old) and his funeral was said to have been ‘well attended’.[v] Two of Margaret's brothers bore his coffin to the grave, suggesting that the families were on cordial terms, despite the difficult beginning.

Questions raised by Margaret’s story

Stories like this one raise many questions that cannot be answered by the historical sources. How did young women like Margaret manage to conceal their pregnancies from those around them and keep up their (very arduous) domestic duties right up to and immediately after birth? How did Margaret manage to convince her mother, who had borne eight children herself, that she was not pregnant? And if she even suspected that her daughter might be pregnant, how could Margaret’s mother leave her without assistance in the Gallop household, to give birth alone? How did a 15 year old girl manage a lone birth – on the floor, with nothing and no-one to help her – without rousing anyone else in the household? And how did she manage the clean-up process without similarly alerting anyone to what had occurred? What was the physical and psychological impact of such a birth on a young girl? However traumatic an event it was, it clearly did not prevent Margaret having many more children. Perhaps she was just lucky and the birth was straightforward. And finally, a question that many such cases at this time present, how clear was the medical evidence in reality? Or were the police, the doctor, the jury (and even perhaps the coroner) happy to seize on any sliver of doubt to avoid a verdict of murder and a sentence of death? We will probably never know!

A note about sources

Most of the stories in this exhibition were drawn from a combination of sources, including official records, mostly held by Public Record Office Victoria (e.g. court transcripts, prison records), other documentary evidence held by the Victoria Police Museum and State Library Victoria, and newspaper accounts. However the court records for the Margaret Walters case could not be found. For this story we were therefore reliant on newspaper summaries of the court proceedings, with confirmation of essential demographic data provided by the Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages Victoria. Locating relevant newspaper articles was facilitated by Trove – the indexing facility managed by the National Library of Australia.

[i] Account from a long article in the Geelong Advertiser, 10 May 1894, p. 3.

[ii] Geelong Advertiser, 16 May 1894, p. 4.

[iii] Reported in the Ovens and Murray Advertiser, 26 May 1894, p. 4

[iv] Geelong Advertiser, 30 May 1894, p. 2.

[v] Geelong Advertiser, 15 May 1920, p. 8