A small army of labourers worked on the docks throughout the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth, loading and unloading ships’ cargo. It was hard work and insecure: most wharf labour was hired on a daily basis, with men seeking work lining up at day-break to sign on. Conditions were basic, with little regard for safety and sick or injured workers were not paid. Before the 1930s most grains and goods were shipped in bags, barrels or crates, but coal was often shipped loose in the holds of ships. Coal ‘lumpers’ were employed to shovel the loose coal into bags for unloading. The work of coal lumpers was probably the most arduous and dangerous of all wharf-labouring jobs. Men working in the ship’s hold shovelling coal worked in clouds of coal dust, while standing on loose piles of coal. If the coal moved they could be pulled down into shutes, or buried under the coal. Hours were long and inhaling coal dust could lead to short-term dizziness. In the long-term it caused serious lung disease. It was said that only the strongest and fittest men could survive as coal lumpers.

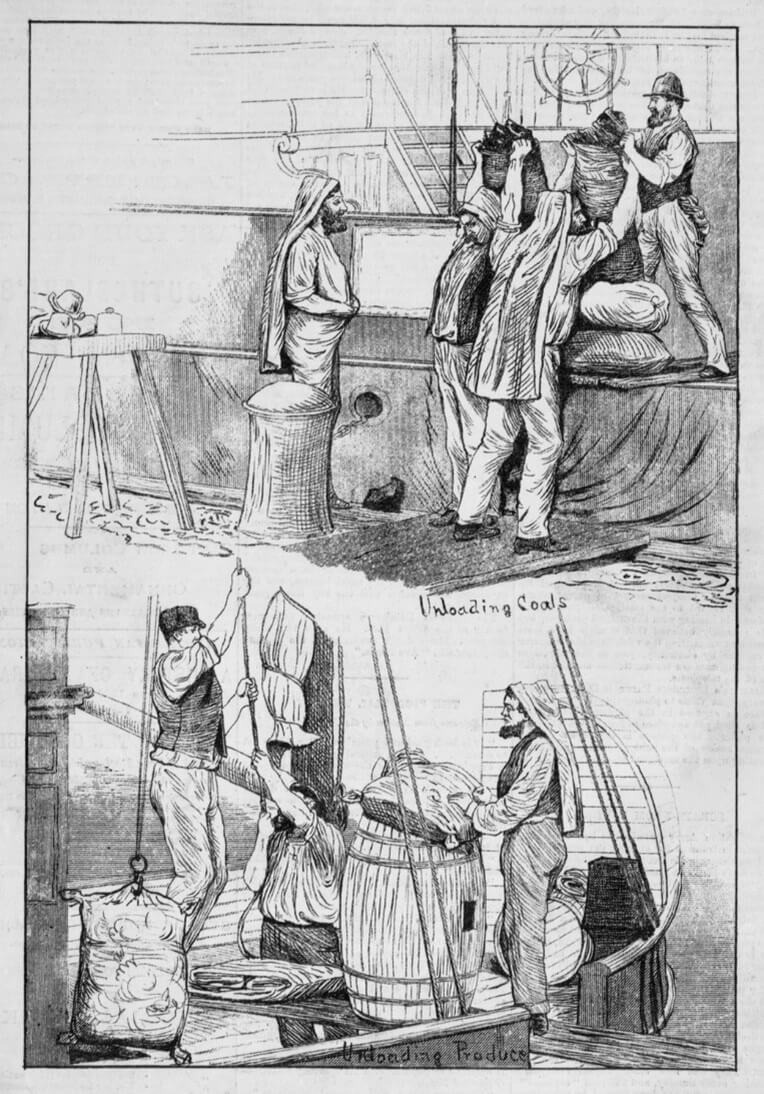

Wood engraving, ‘Sketches on Queen’s Wharf’, Australian Pictorial Weekly, 24 July 1880

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

This wood engraving from 1880 shows coal lumpers above and men unloading ‘products’ below. Several of the men wear a kind of cape over their heads and backs, to protect their skin from the rough hessian bags they carried. The bags of coal were filled to overflowing and must have been extremely heavy to carry. It is now hard to imagine doing this kind of work for eight or more hours each day.

Grain was shipped in bags. The grain was bagged on the farm and transported either by wagon, or later by rail or coastal shipping to the wharf for export. Grain ‘humpers’ moved the bags to and fro. Each bag weighed about 60 kilos, sometimes more than the man himself. Grain ‘humpers’ used similar capes to other wharf labourers to protect their necks from the rough hessian bags. Later grain was moved by conveyor belts and stored in bulk silos before shipping. Bulk handling was introduced progressively from the 1930s, reducing the need for manual labour.

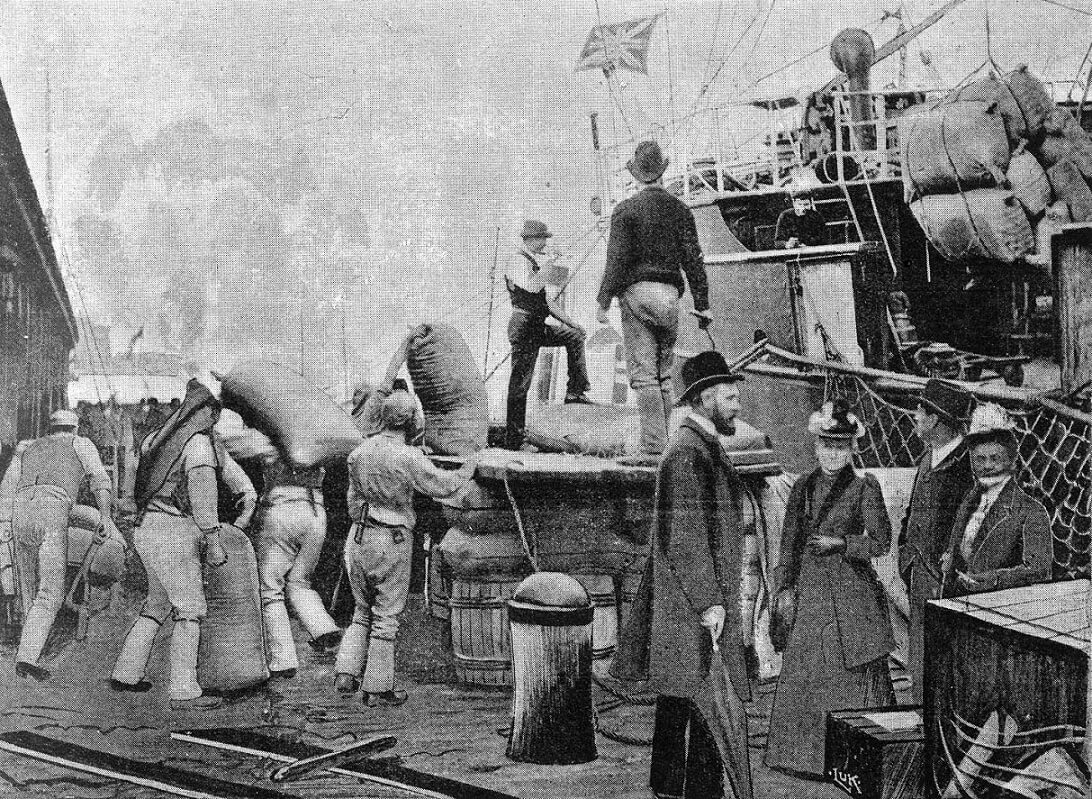

Working cargo, Queen’s Wharf, 1893

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

This print was published in the Illustrated Australian News on 1 September 1893. It shows wheat humpers (or lumpers) carrying large bags, probably of wheat, on their backs. Some are wearing the distinctive cap and cape that protected their necks and shoulders from the hessian bags. The bags are being lifted onto the wharf from the ship’s hold with the aid of a pulley system. The man wearing a jacket and standing on the platform may be holding a wharfie’s hook to help lift the bags for the humpers. A group of prosperous onlookers stands in the foreground.

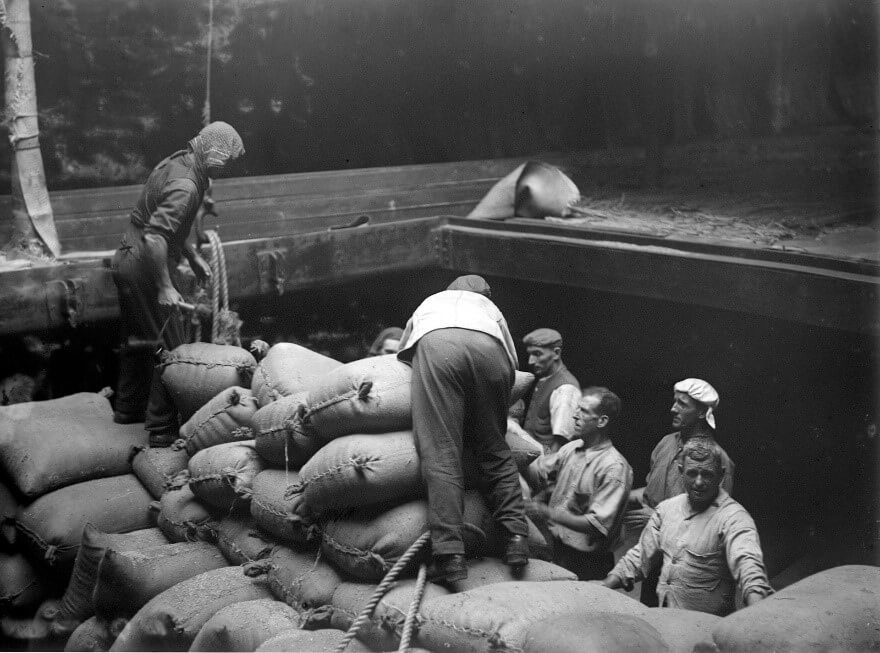

Loading wheat, Port Melbourne, c. 1920

Alan C. Green Photographer

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

The worker to the left of the photograph is holding a wharfie’s hook, used to help lift hessian bags and bales.

Loading wheat, Port Melbourne, c. 1920

Alan C. Green Photographer

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Wharf labourers were also known as wharfies, or more formally as stevedores. They used hooks like this one to lift and guide hessian bags and bales. This particular hook was used by the late Rob Clyde of Port Melbourne. He worked on Melbourne’s waterfront for more than 40 years.

Wharfie’s hook, 1950s

Courtesy City of Melbourne Art & Heritage Collection

Using a wharfie’s hook, Victoria Dock, 1938

VPRS 8363/P2, unit 2, item 50177

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

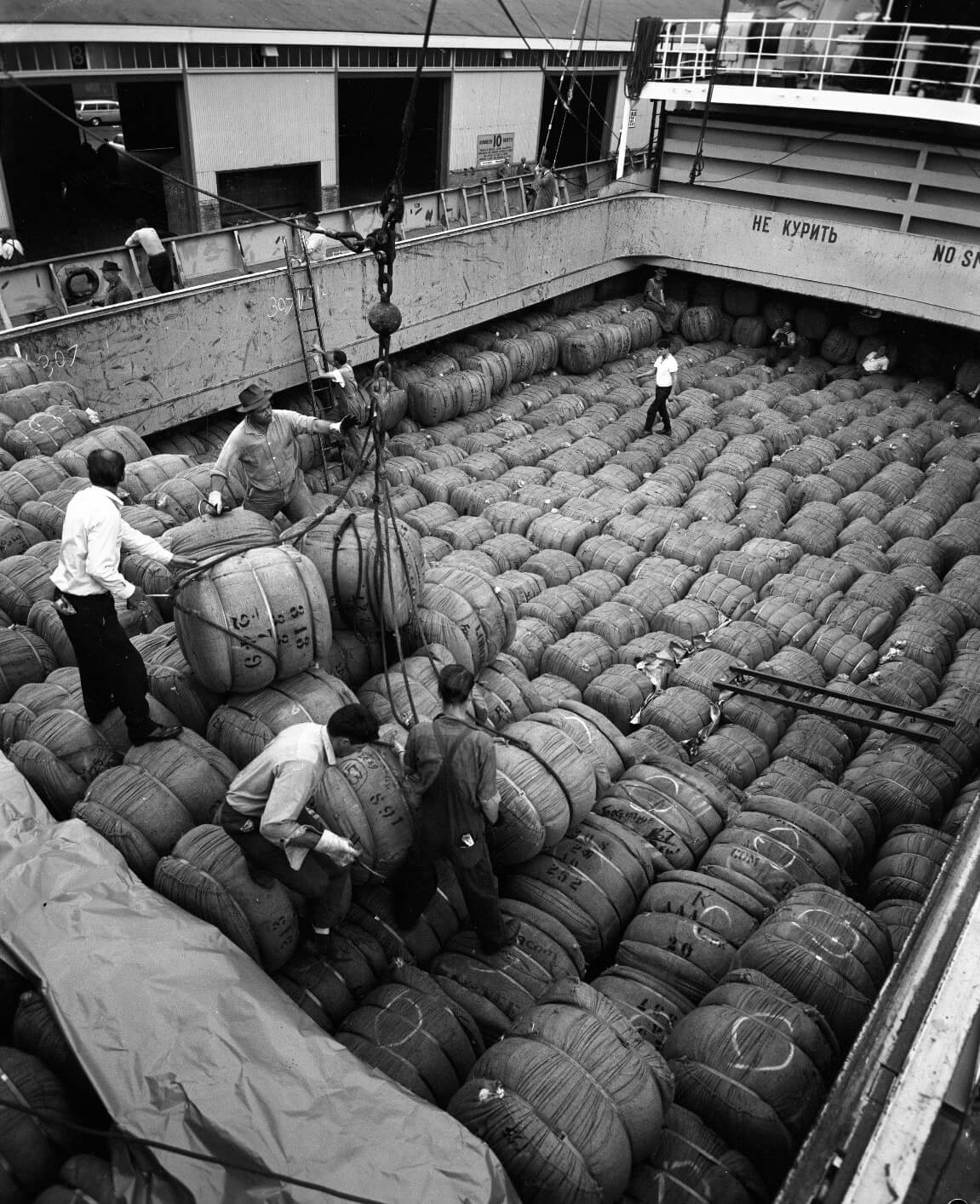

The cargo here is wool bales. Over the years there were many disputes about the size and weight of bales, especially as new pressing technologies pressed more wool into the same volume, increasing the weight of the bales.

Wool cargo, c. 1940

VPRS 8363/P2, unit 2 item 68134

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

Loading wool bales, c. 1950

VPRS 8363/P2, unit 2, item 50165

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

Metal barrels on Victoria Dock, 1938

VPRS 8362/P1, unit 9, item 305

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

Mechanisation

Loading crates & sacks, Victoria Dock, c. 1920

VPRS 8362/P1, unit 9, item 299

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

A complex system of strong nets and pulleys is shown lifting cargo aboard in this photograph. The sacks in the foreground may contain mail. Men in suits are supervising.

Mechanisation gradually made moving cargo less arduous, but also replaced workers. This photograph seems to show an early version of the fork-lift truck, possibly operated manually, and shown shifting cargo on Victoria Dock. Fork-lifts were first invented in the early 1900s. The man on the right may be demonstrating the operation of the machine, since his suit suggests that he is not a wharf labourer.

Victoria Dock, 1927

VPRS 8362/P1, unit 4, item 399

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

Mechanisation improved efficiency on the wharves. It helped to make wharf labour less arduous, and probably reduced the rate of workplace injury, but it also began the inexorable process of reducing the need for labour. Bulk-handling of grain and liquids was especially important, introduced gradually through the 1930s. Storing grain in silos rather than bags also greatly reduced losses from mouse and other pest infestation. The grain was transferred from the silos and into the ships’ holds by conveyor belts, eventually replacing the need for grain ‘humpers’ altogether. Liquids like oil and motor fuel were also stored in large bulk silos, often near the ports.

Opening of Geelong wheat silos and wharf loading equipment, 1939

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

The silos and conveyor belt were built by the Victorian Government.

Containerisation was the next major innovation in the management of cargo. From the 1960s in Victoria an increasing volume of cargo was shipped in large containers, which were loaded and unloaded from vessels by machine. Once in the containers, the contents were not handled until they reached their final destination, reducing the need for wharf labour significantly. Melbourne is Australia’s largest container port.

Bulk flour wagon, 31 August 1966.

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

Ship loaded with containers, Port of Melbourne, no date

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

Patrick Stevedoring Company loading containerised cargo, no date

Reproduced courtesy Public Record Office Victoria

Maritime unions

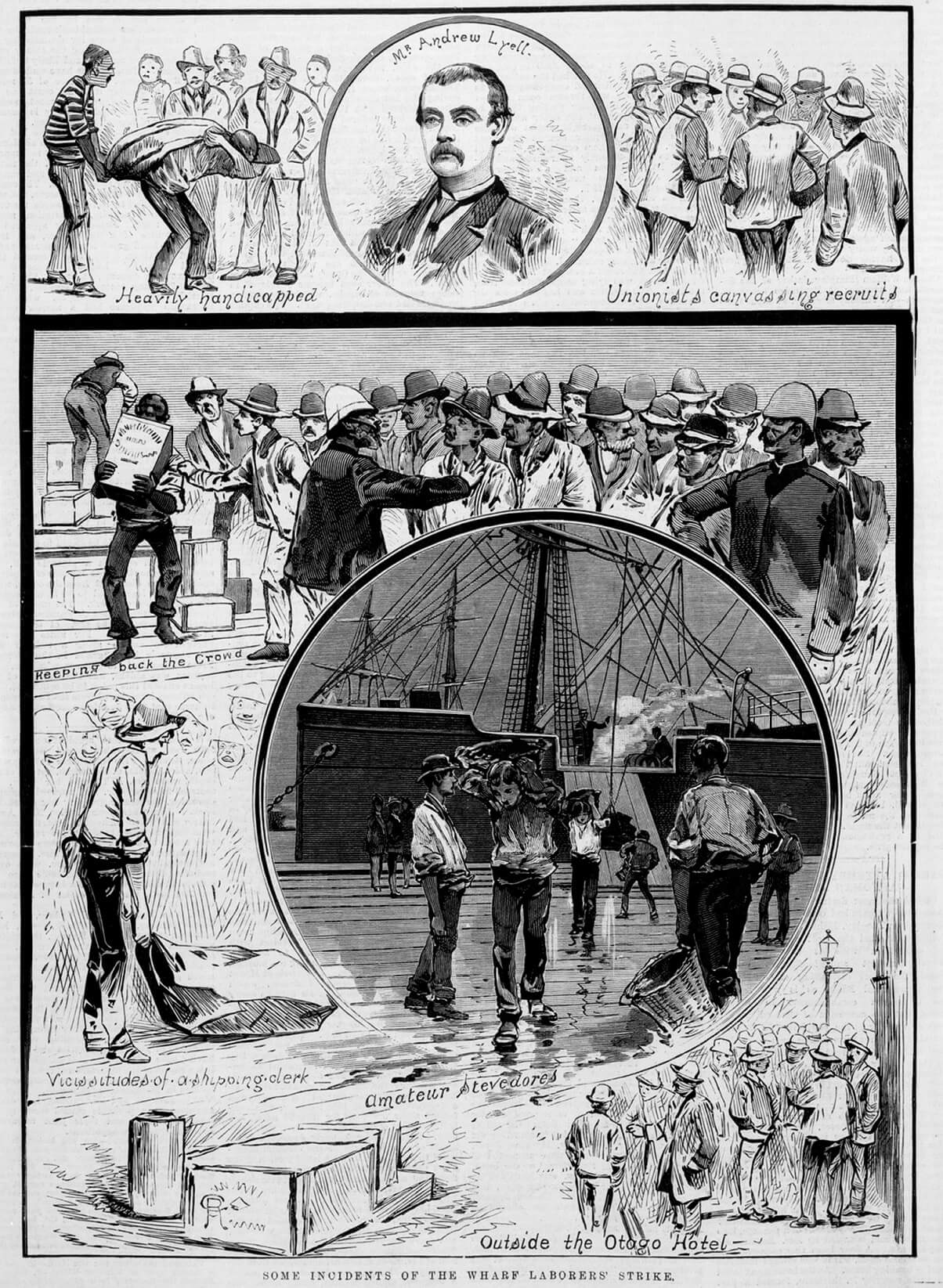

In the late nineteenth-century two maritime unions were formed in an attempt to improve conditions for workers. The Melbourne Seamen’s Union formed in 1872 and in 1876 amalgamated with the Sydney union. A Wharf Labourers’ Union formed in 1884. Employers responded by trying to exclude union members, prompting strike action, including this strike in February 1886. A major strike in 1890 brought much of the colony to a standstill, as maritime unions joined with shearers, miners and transport workers across the country. Strikers were defeated in the end by an economic downturn that deepened into a nationwide depression.

Some Incidents of the Wharf Laborers’ Strike, The Age 3 February 1886

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

After Federation the various state-based waterside unions decided to amalgamate to create a federal union — the Waterside Workers’ Federation of Australia (WWFA), formed in February 1902. W.M. (Billy) Hughes (later Prime Minister) was its first president. In 1906 they argued successfully in the Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration to establish the right of workers employed under the federal maritime award to ten days of paid annual leave. This was the first such ruling.

The 1928 strike

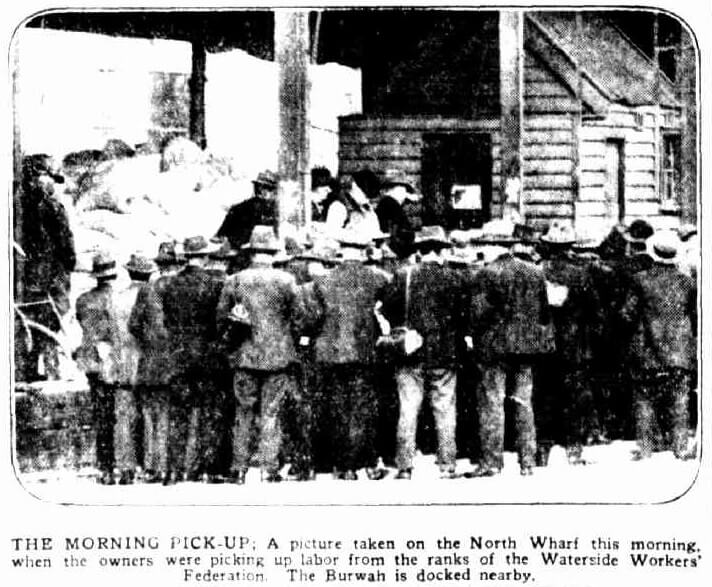

The waterfront was a turbulent industrial environment throughout the period after the First World War, partly provoked by conservative government fears associating unionism with Bolshevism, and partly by employer anxiety that acceding to requests for better pay and conditions would make them less competitive. In 1928 workers reached breaking point when employers attempted to enforce a change to the waterside workers’ award requiring two pick-ups per day. This meant that workers were required to line up twice each day for work, meaning that those unsuccessful in the morning had to wait around on the docks all day for the chance of work later in the day. Workers in several major ports around the country refused to attend the pick-ups, effectively striking. After some days the WWFA recommended a return to work, but workers in Melbourne refused. In response the Australian Government passed an amendment to the Transport Workers Act requiring all waterside workers to be licensed, creating an opportunity for employers to bring in ‘volunteer’, strike-breaking (‘scab’) labour. The Federation was also fined for allowing its members to strike. To add to the escalating tension, some of the ‘volunteer’ workers were recently-arrived Greek and Italian migrants, adding ethnic prejudice to the already-toxic mix.

By late October the majority of ships were being serviced by scab labour and regular fights broke out on the wharf. The premises of some Greeks and Italians were bombed. On 2 November there was a violent confrontation as unionists tried to break through a police cordon protecting one of the ships using ‘volunteer’ labour on Princes Pier. The police were ordered to fire into the crowd and four unionists were wounded. One, returned soldier Alan Whittaker, later died of his wounds. Over the following weeks most unionists who could returned to work. However the repercussions from the 1928 strike continued for decades, not least because two unions thereafter competed for work — the WWFA and a new union, the Permanent and Casuals Wharf Labourers’ Union, comprising those brought in to break the strike. In time the two rival unions would bury their differences, but it took many years.

Herald 21 September 1928, p. 24

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

A newspaper photograph of men from the WWFA lining up for selection for the morning shift in September 1928.

Waterside workers and seamen demonstrate outside the Commonwealth Industrial Court Building, 1958.

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

The waterfront continued to be turbulent during the period after the Second World War. Full employment allowed unions to bargain for better wages and conditions and the unions were powerful protectors of their members. In 1951 the WWF absorbed the former Permanent and Casual Wharf Labourers’ Union, increasing its bargaining power. In 1958, when this press photograph was taken, workers were demonstrating against attempts to reduce the size of gangs on the wharf, citing safety concerns and the high rate of accidents. Previously the unions had organised workers into gangs and rotated members to share the work equally, effectively contracting with employers to supply the workforce. But maritime unions were still regarded as radical unions by employer groups, which continued to seek to reduce their bargaining power.

The battle between employers and unions continued well into recent times. One particularly bitter and extended dispute took place in 1997-8 when the Maritime Union of Australia, formed by an amalgamation in 1993 of the Waterside Workers’ Federation and the Seamen’s Union, opposed an attempt by Patrick Stevedoring Corporation to restructure its business, sacking its union workforce and replacing them with non-union labour. In the resulting lock out of workers, the union established picket lines on the docks, attempting to keep out ‘scab’ workers. Patrick was supported by the Federal Liberal Government, which argued that reducing the power of the unions would increase productivity on Australian wharves. Legal action, which progressed all the way to the High Court, eventually saw union workers reinstated, but with a reducing workforce to be achieved through voluntary redundancies and changes to work practices. In the intervening years bulk handling and containerisation had already cut the maritime workforce significantly, also reducing the resources of the maritime unions.