Lieutenant-Governor Latrobe… was possessed of the idea that diggers could be better controlled, politically, morally and physically, if they were made as far as possible total abstainers. From his Moravian missionary point of view he was possibly right. Hence he caused a "prohibition" law to be issued, under which it was a penal offence to sell liquor on any goldfield. The establishment of public houses was absolutely prohibited. No man was allowed to have in his possession more than two gallons of spirituous or fermented liquors. If a man were suspected of having a greater quantity, the police had the power, which they most rigorously exercised, of entering and searching house or tent in pursuit of it. Search warrants were not required. The old British belief that "an Englishman's house is his castle" was rudely upset, and the way the prohibitory laws were carried out was cruel in the extreme.

Leader, 23 April 1887

On every flat, on every hill-side, and in every gully sly-grog shops were established and flourished. The authorities burnt them down, fined and imprisoned their owners, and still the abounded. It seemed as if pruning down these elicit [sic] offshoots of the liquor traffic only sent up 10 new shoots worse than those destroyed.

Mount Alexander Mail, 25 August 1885

Gold was discovered in Australia in 1851 — first in New South Wales and then Victoria. All over Australia men downed tools and rushed to the goldfields. News of the Victorian gold discoveries soon reached the world and during 1852 alone, 45,000 passengers from Britain arrived in Victoria, most of them gold-seekers. They were joined by thousands of immigrants from Europe, America, China and New Zealand, keen to try their luck.

Hard work and hard liquor made the Victorian goldfields a riotous place. Drunkenness and theft were common, and law and order became a serious problem for the colonial government. Lieutenant-governor Charles La Trobe believed that ‘spirits [were] the root of nine-tenths of the crime and disorder on the diggings’ and, in a vain attempt to limit lawlessness, the sale of alcohol was banned in 1851.

Prohibition, however, had very little effect, and the law was mocked. Diggers continued to drink, finding plentiful illegal supplies. ‘Sly-grog’ shops, disguised as cafes and stores, sprung up in every gully and on every field. Liquor was never in short supply. Author and digger, William Howitt, wrote in 1852:

All over Ballarat bottles broken and whole lie about in such quantities, that it is wonderful how horses go anywhere on the field without getting lamed. There was a pool down in the basin, not very far from the camp, into which literally thousands of bottles were thrown. Before all the public-houses on the road, there lie heaps, sometimes of many wagon-loads, and all along the bush you still find them, some dashed against the trees, and others still whole.

Bad Liquor and Bad Company

Had there been licensed houses on the diggings, as there were all over the colony, and as there were afterwards on the goldfields themselves, one half of the crime and suffering from bad drink would have been avoided.

‘Reminiscences and adventures. By an ex-official,’ Leader, 23 April 1887

Prohibition failed to stop drinking on the diggings. Instead, it fuelled an unregulated, unsupervised ‘grog trade’. Sly grog was, in nearly every case, badly adulterated. In 1853 a government inquiry into the sly-grog industry heard that the grog was produced from cheap liquor with additives such as tobacco and pharmaceutical spirits. One cocktail, fittingly called 'Blow my head off', was found to contain Cocculus indicus (poisonous Indian berries), spirits of wine, Turkey opium, Cayenne Pepper, rum and water. Many a gold digger was killed by the bad liquor. According to one, Thomas Carte, ‘the greatest curse of all was the fiery liquid that was sold under the name of brandy, for it drove many of the diggers mad and sent many to an untimely grave.’

Sly grog tents became havens for criminals. The Argus reported in February 1852 that sly grog shops were ‘infested by a set of pick-pockets and midnight robbers, who, sleeping all day, prowl about the tents at night to ease the hard working digger of his gold.’ Diggers were sometimes served a ‘knock-out drink’, rendering them unconscious and easy prey for thieves. It took some ‘courage’, Antoine Fauchery claimed, to accept the offer of a drink in a sly-grog shop:

‘Good Lord! this Bourchardy stage-setting, these muffled tremolos from the orchestra, these uneasy glances into the wings, these strange gestures, you might almost say these trap-doors – all this for a glass? – Yes indeed, and what awful brandy at that.

Drunken customers gambling, arguing and fighting were common problems. In April 1853, painter and gold digger Eugène von Guérard wrote in his diary:

Some days ago a large tent was put up close to mine by some very undesirable-looking people. A man with a wife and daughter, and several young men, seem to share it. They possess carts and horses, and seem to be carrying on an illicit sale of spirits. The gambling at night invariably ends in loud quarrelling and fighting. Very unpleasant neighbours.

Mary Anne Allen, living on the goldfields with her husband and eight children, had similar complaints:

Part of the time we were near a store (a sly grog shop) which was soon removed by the vigilance of the police… drunkenness and fighting, profanity & robberies were very common and we were frequently alarmed by cries of murder.

A Risky Business

Raids were sudden and severe. It was no uncommon sight, for example, to see a man’s tent or bark hut suddenly surrounded by a score or so of policemen with fixed bayonets, under the command of a mounted officer. These policemen, without any search warrant, or any legal authority but the bidding of their officer, would enter the dwelling, search and ransack it from roof to roof, and, if finding nothing contraband, proceed to another tenement to serve it the same way. If any greater quantity than two gallons of liquor was found, the owner’s property was doomed. A brand would be snatched from the fire, and in a few minutes a man’s home and his property would be reduced to tinder and ashes. If he possessed any property, such, for example, as a cart, wheelbarrow, washing-cradles, tubs &c., all were cast indiscriminately into the flames.

Bendigo Advertiser, 6 October 1888

If caught, sly-groggers had their stock confiscated and were ordered to pay a fine, or face months in gaol. Police raids on sly-grog tents were common, and sometimes brutal. Superintendent Armstrong —‘a strong, powerful, fearless specimen of a human beast’ — was notorious for his standover tactics. He ordered the tents of alleged sly-groggers to be burnt, and beat those who questioned his methods with the brass knob of his riding crop:

Armstrong rode a high spirited charger, and acted as marshal. I never knew him to wear uniform or carry arms. I think he despised both, but he always had a heavy metal hammer headed riding whip, with which I have seen him fell his opponents in a scrimmage. At the word of command the little army surrounded a low, long, bark hut on the edge of the green fringe of peppermint bushes that grew along the upturned ground. The diggers away down the gully saw at once that "some-thing was up," and they swarmed out of their holes. They threw down their picks and shovels. The men at the tubs ceased to wash their dirt. The cradles on the edge of the creek stopped rocking. A crowd of clay stained stalwart diggers swarmed up to the scene of action. Too well they knew the law-less nature of the chief actor.

Two foot police entered the dwelling and brought out the proprietor and his visitors under arrest. They were fastened to a bullock chain, under guard — sabre and trigger. The police re-enter and ransack the place. They dig up the floor to find contraband rum. They tear down suspicious linings and overturn boxes and bales. In triumph they bring out a couple of kegs, some square bottles of gin and sundry specimens of other liquors. The crowd is excited, and is increasing in volume, because the owner of the sly-grog shanty is a popular favorite. They surge up to the police circle; and Armstrong, with bloodshot eyes and stentorian tones, waves them back. They know the man they have to deal with, and stand irresolute. Meanwhile, a policeman approaches with a firebrand. A few seconds and the hut with all its contents, is in flames. The police mutely watch the conflagration.

Armstrong sees a spring cart lying in the shade of an old gum tree. It belongs to the shantykeeper, and is, therefore, under orders, ruthlessly backed into the flames. There is some harness on yonder sapling. It shares the fate of the spring cart. Tubs, buckets, tools — all that the man possesses — are hurled on the embers, and then the prisoners are marched off. Some are fined and let loose the next day. The keeper of the shanty is fined £50, or consigned to six months.

As the cavalcade moves off angry murmurs fill the air. The diggers will not keep back. An angry menace is on every brow, but this is just the atmosphere which Armstrong likes. He glories in it. His blood is up, and he charges the crowd, laying a few low with his formidable heavy headed whip.

Police had an incentive to ‘hunt’ down the sly-groggers, with half the proceeds of the fine going to the policeman responsible for the conviction. Unsurprisingly normal police functions were neglected and blackmail and perjury commonplace. Unquestionably the innocent often suffered with the guilty. Superintendent Armstrong was widely suspected of sheltering the larger liquor dealers and of having £15,000 when he retired.

Police could not eradicate the illicit sale of spirits. Selling sly grog was so lucrative that many were prepared to take the risk, creatively concealing their activities:

For example, there was a well known, stout, rubicund fellow who used to appear amongst the holes on Bendigo Creek about noon. He could be recognised half a mile off by the wonderfully tall felt hat he wore. In this hat and carefully balanced on his head he carried something like a demijohn of rum, which he dispensed during his pilgrimage at 2s. 6d. per small nobbler.

The diggers also helped to protect their own. If police were sighted on the field a warning cry was raised and the sly-groggers were hidden until the danger passed: ‘The proof of sale could not be got, for not one amongst the diggers would ever dream of either giving information or assisting the police…’

Women and Sly-Grog

Big Poll the grog seller gets up every day,

And her small rowdy tent sweeps out,

She’s turning in plenty of tin, people say,

For she knows what she’s about,

For she knows what she’s about.

Polly’s good looking, and Polly is young,

And Polly’s possessed of a smooth oily tongue;

She’s an innocent face and a good head of hair,

And a lot of young fellows will often go there…"

Poll the grog seller.

Charles Thatcher, 1864

Many a digger’s wife found useful employment selling sly-grog. Some used clever tactics to hide their illegal activity. One woman on Bendigo flat ‘used to come down amongst the men bearing a yoke and a pair of milk-pails both filled with liquor’. Some hawked their grog around in a kettle, ‘on the pretence that it contained nothing more invigorating than a drop of cold tea.’

Inevitably, and possibly unjustly, prostitution was linked to female grog sellers. Historian, Margaret Anderson, points out:

Respectable observers of goldfields life were horrified by the activities of these women and tended to associate them with every conceivable vice, but their perceptions were undoubtedly coloured by middle-class assumptions about appropriate female behaviour and they may well have exaggerated what they saw.

After three short years, prohibition was accepted as a ‘mere farce’, and abandoned in 1854.

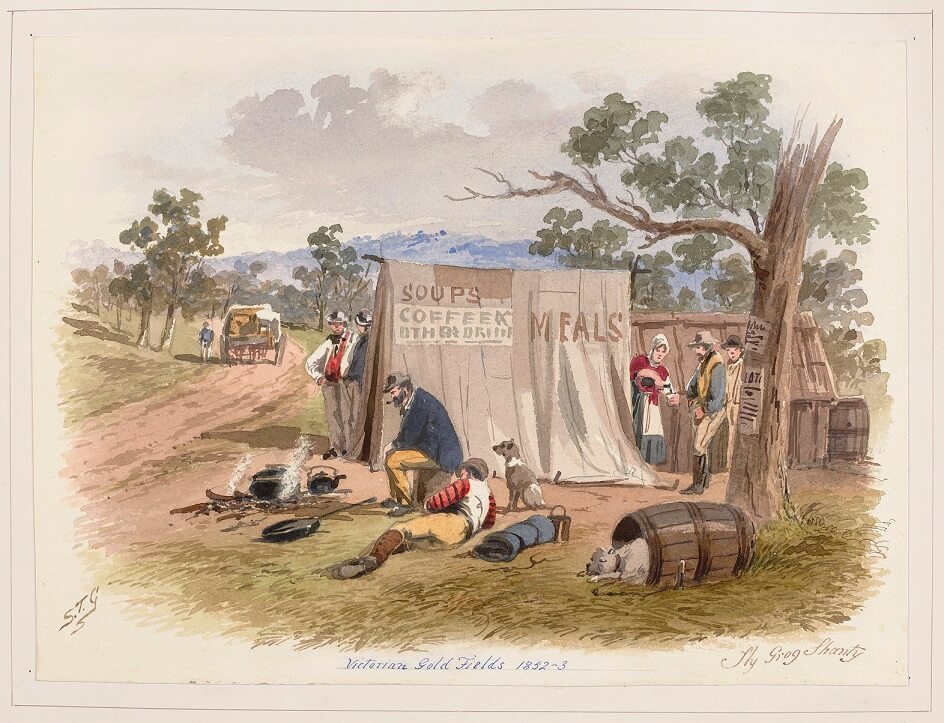

‘Sly Grog Shanty Victorian Gold Fields’, by S. T. Gill, artist, 1852-3

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

On the goldfields, tents selling coffee or meals often functioned as fronts for sly-grog selling. In this picture by goldfield artist, S. T. Gill, a woman serves grog to two men from the rear of the tent, while others keep a look out in front.

The sly grog tent attracted a lively trade on a Sunday. Author, William Howitt wrote:

[T]here was Mrs. Bunting, an enormously fat woman. Her husband was a storekeeper; but Mrs. Bunting cut the first figure in the establishment. She was well known as a sly grog-seller, and has been fined some dozen times or more, from 20/- to 50/-a time; but she did not care for it, she still went on, and set the law at defiance… on Sundays, when the other stores were closed, she had a large placard up in front of hers, with ‘Gold bought this day’.