Gold was discovered in Australia in 1851 – first in New South Wales and then in Victoria.

The effect of the discoveries was electrifying. Here at last was a chance for independence from a life of wage-labour. A chance, with real luck, to make a fortune most could only dream of.

All over Australia men downed tools and left for the goldfields. Australia’s first gold rush had begun!

Melbourne – a city in chaos

As working men rushed to the diggings, businesses foundered and banks were stripped of cash to buy supplies. Prices soared as the city teemed with eager gold-hunters. Deserted wives and families struggled to pay for basic food and clothing.

Watercolour by William Strutt, from the album ‘Victoria the Golden’, c.1851. Reproduced courtesy Victorian Parliamentary Library

This painting shows the plight of women in Melbourne during the gold rush. Without men to perform traditional male tasks, the women filled their shoes and chopped wood, fetched water and mended houses. One-third of Melbourne’s adult male population was said to have left for the diggings.

In reporting to his superiors in London, Lieutenant-Governor Charles La Trobe wrote, ‘all government works are at a standstill… Cottages are deserted, houses to let, even schools are closed. In some of the suburbs, not a man is left.’

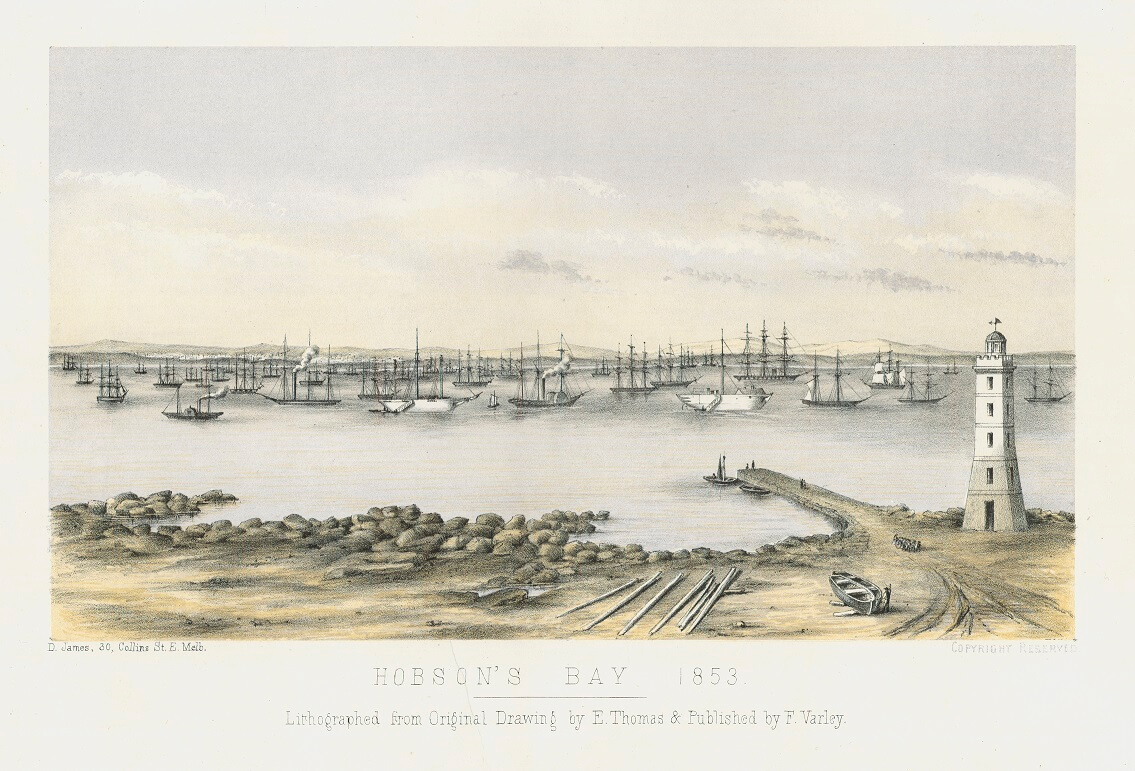

Watercolour by Edmund Thomas, 1853. Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

By 1852 ships were arriving in the Port of Melbourne at the rate of two or three per day. Many sailors promptly deserted to seek gold, sometimes even scuttling their ships. There were stories of captains having to increase wages tenfold to lure crews back to England.

The news spreads

News of the Victorian gold discoveries soon reached the world. On 8 April 1852, the Times in London reported £730,242 worth of gold, ‘and where it is to end no human being can guess.’

During 1852 alone, 45,000 passengers from Britain arrived in Victoria – most of them gold-seekers. They were joined by thousands of immigrants from Europe, America, China and New Zealand, keen to try their luck.

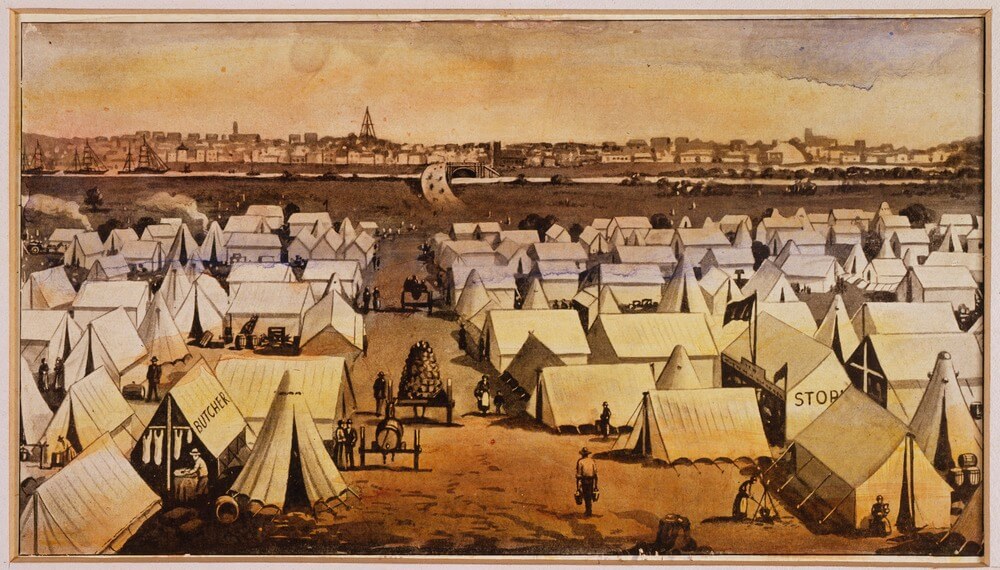

‘Canvas Town, between Princes Bridge and South Melbourne in the 1850s’. Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Melbourne’s population in 1851 was 23,000. In just four months in 1852, 619 ships arrived carrying over 55,000 passengers. Accommodating the new arrivals was impossible. Hundreds spent a night or more on the wharves among the barrels and bales. Thousands more went to ‘Canvas Town’, a sprawling tent city on the south bank of the Yarra River.

A colony transformed

In the following decade Victoria was transformed. In 1851 Victoria had a population of 97,000 people. That number skyrocketed to 237,000 by 1854 and 411,000 by 1857. By 1861, the population of Victoria was 540,000 – half the total population of Australia. As regional towns sprang up around the goldfields, farming and industry followed to support them.

Between 1851 and 1861 Australia exported at least 30 million ounces (850 metric tons) of gold - more than one third of the world’s total.

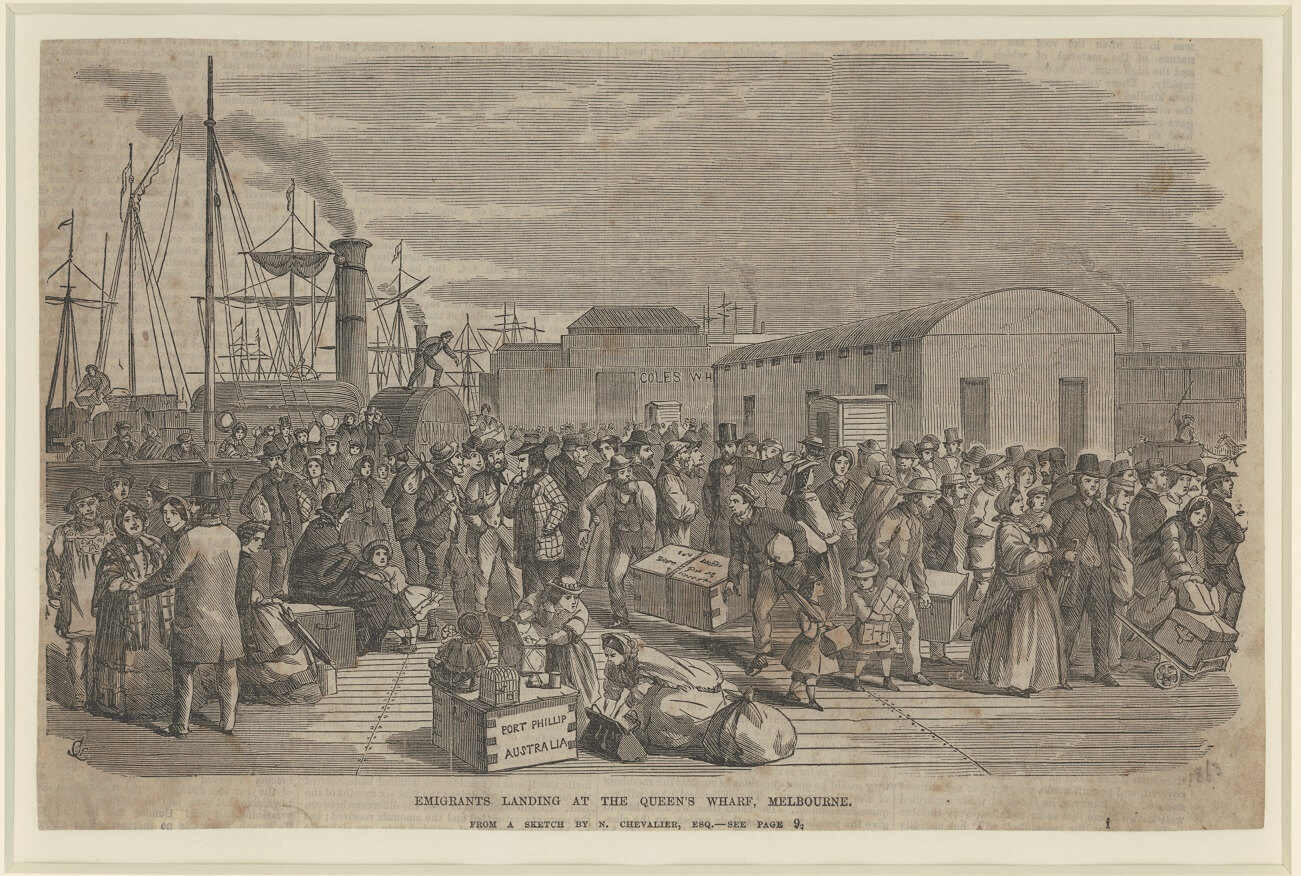

Emigrants landing at the Queen’s Wharf, Melbourne, 1850s

Reproduced courtesy National Library of Australia

After three or four months at sea, the gold-seekers arrived in Melbourne, gathered equipment and set out to walk to the diggings.

The road to the diggings

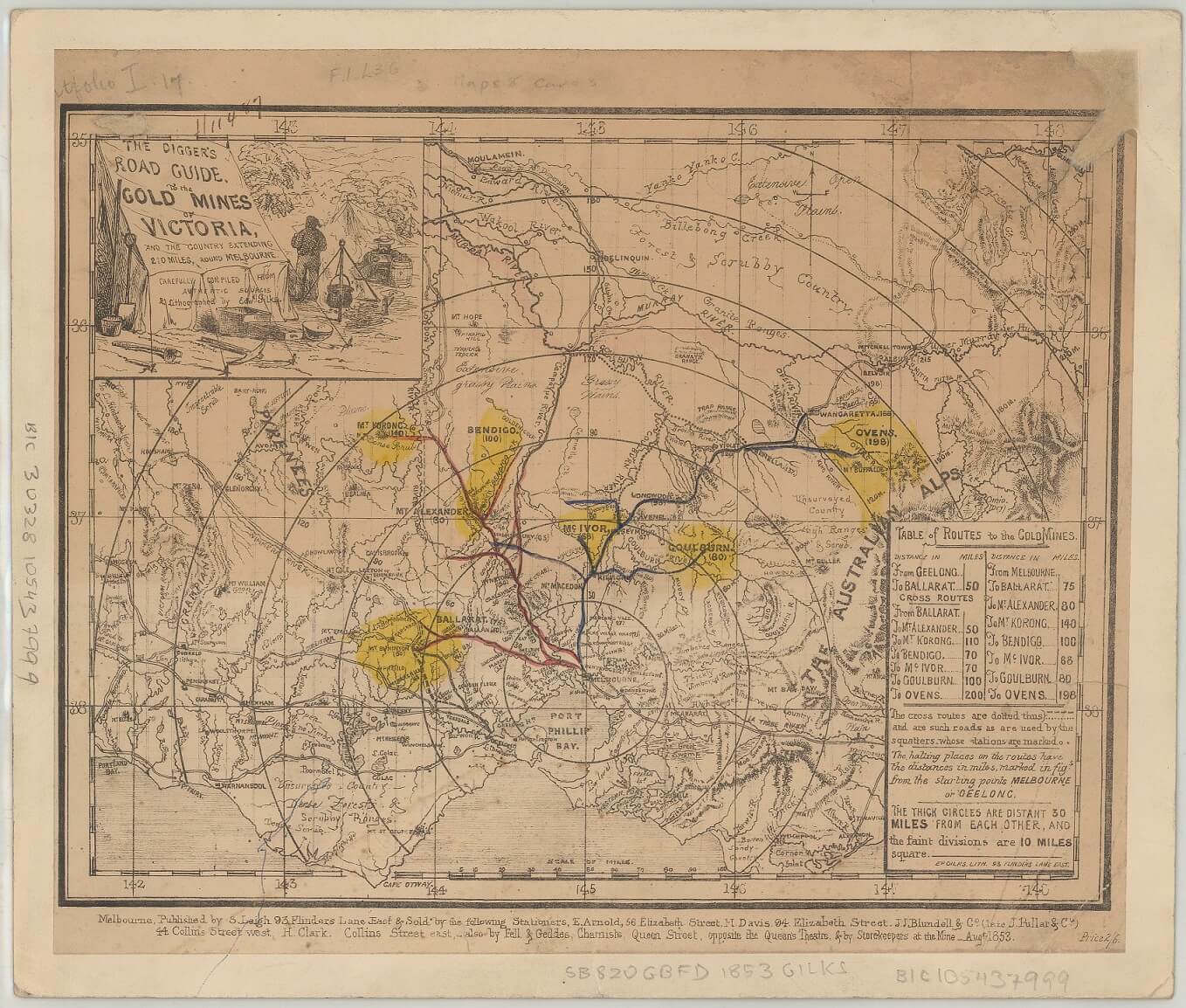

At the peak of the gold rush a crowd, hundreds strong, laboured up Elizabeth Street to Flemington Road every day. From there they branched off to the fields. Ballarat was a three-day walk, Bendigo took from three to five days, while the Ovens fields could take weeks in winter.

‘The digger's road guide to the gold mines of Victoria, 1853’. Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

In the 1850s the mining districts were Ararat, Ballarat, Ovens (Beechworth), Maryborough, Castlemaine, Sandhurst (Bendigo) and Gippsland. Some fields became home to thousands in just a few days and were deserted just as quickly when the easy gold ran out, or there was news of a richer strike.

Although a coach service to the diggings was quickly established, most set out on foot. The ‘roads’ were mere dirt tracks - boggy in winter, baked dry and dusty in summer. In the wet weather those on foot ‘crawled like flies across a plate of treacle’, and for those with carts it was worse:

Sticking fast; loading and unloading in consequence; digging wheels out of the terrible quagmires; heaving at them with poles for levers; shouting, flogging, swearing, straining – that is the everyday work on the roads.

William Howitt, Land, Labour and Gold, 1855

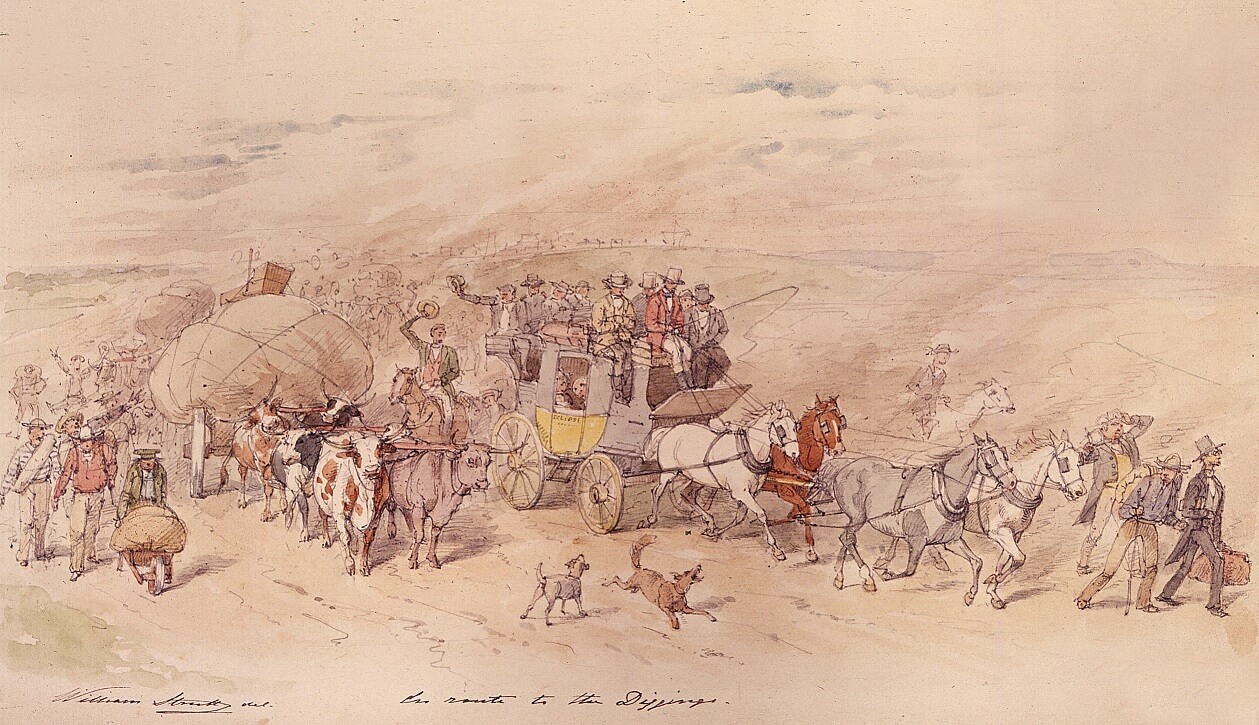

Watercolour by William Strutt, from the album ‘Victoria the Golden’, c.1851. Reproduced courtesy Victorian Parliamentary Library

Hopeful diggers set out from Melbourne to the goldfields. Some can afford the coach, with their luggage carried by cart, while others must go on foot.

Watercolour by Samuel Thomas Gill, 1869, from a sketch completed in the 1850s. Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

In this painting S. T. Gill captures the essence of the long, dry and dusty trek to the Victorian goldfields. Unusually a child accompanies the diggers.

Of those who went from a port to the goldfields in the early 1850s, most walked the whole way. Loading themselves with a small tent, blankets, pick and shovel and pan, cooking implements and perhaps a little flour and tea, they staggered along the road.

Sometimes they tie their victim to a tree and leave him to the ants, mosquitoes and hunger. Very rarely is the unfortunate found in time. More often one finds a skeleton tied to a tree.

Polish miner, Seweryn Korzelinski, travelling to the diggings in 1852

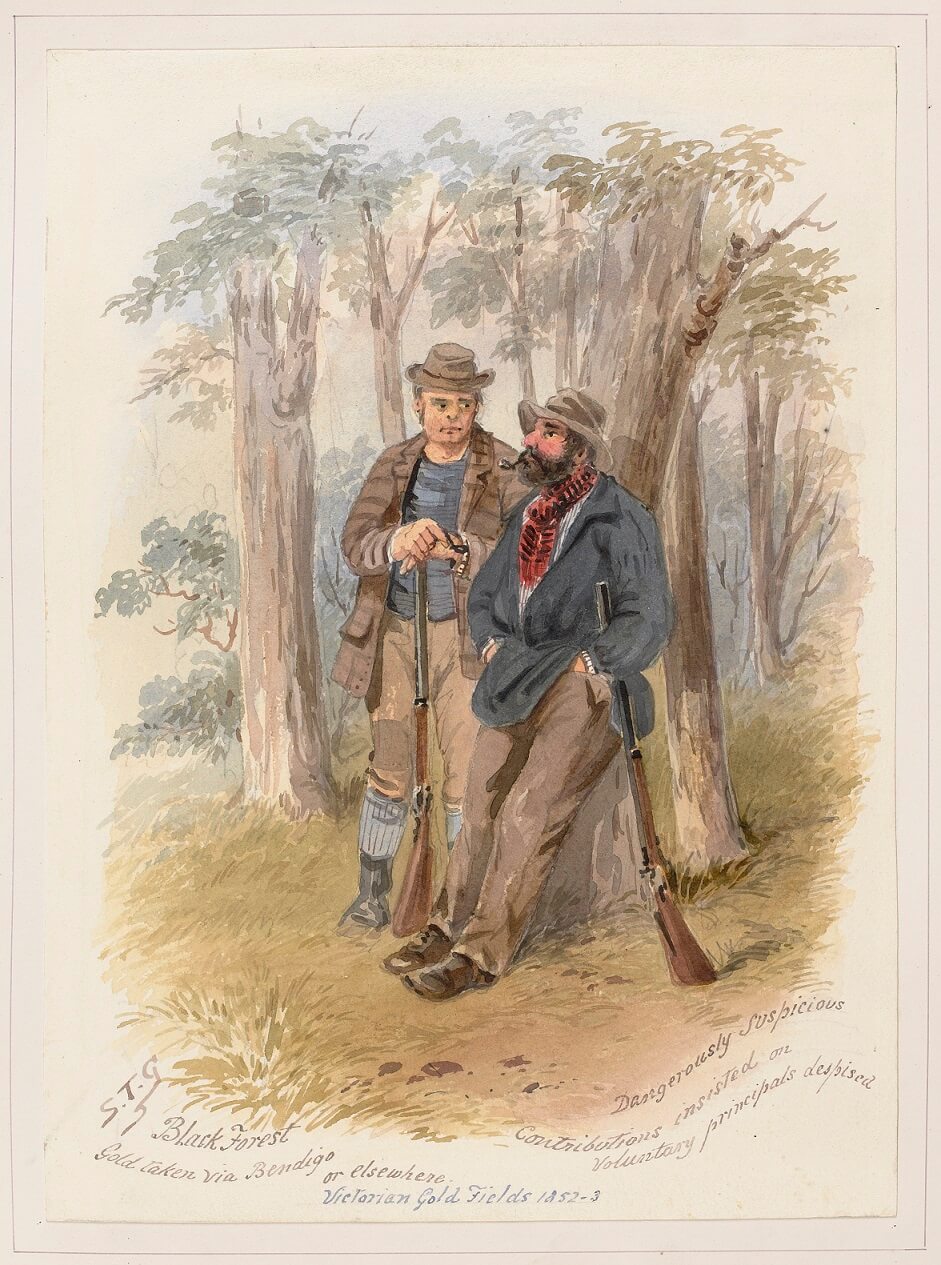

Watercolour by Samuel Thomas Gill, 1869, from a sketch completed in the 1850s. Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Thieves and bushrangers lurked along the roads to the goldfields. The Black Forest, a twelve-mile stretch of dense bush en route to the Castlemaine and Bendigo goldfields, was particularly feared.

Arriving at the goldfields

The first view of a goldfield was a sight not soon forgotten. Antoine Fauchery described the Ballarat fields ‘…with as many holes as a sieve, seeming to have been turned upside down by cyclopean ants’. To Mrs Elizabeth Massey the goldfields resembled ‘one vast cemetery with fresh made graves’.

Some enjoyed the novelty. For Ellen Clancy visiting in 1852, the view ‘well repaid our journey even of sixteen thousand miles’. Others, like William Howitt, were less impressed:

… to the left, up the valley, hundreds on hundreds of tents are clapped down in the most dusty and miserable places; and all the ground is perforated with holes, round or square… you must tread your way carefully amongst them, if you don’t mean to fall in… There is the creek or little stream – Spring Creek – no longer translucent as it comes from the hills, but a thick clay puddle, with rows of puddling-tubs standing by it, and men busy working their earth in tins and cradles.

Ellen Clancy

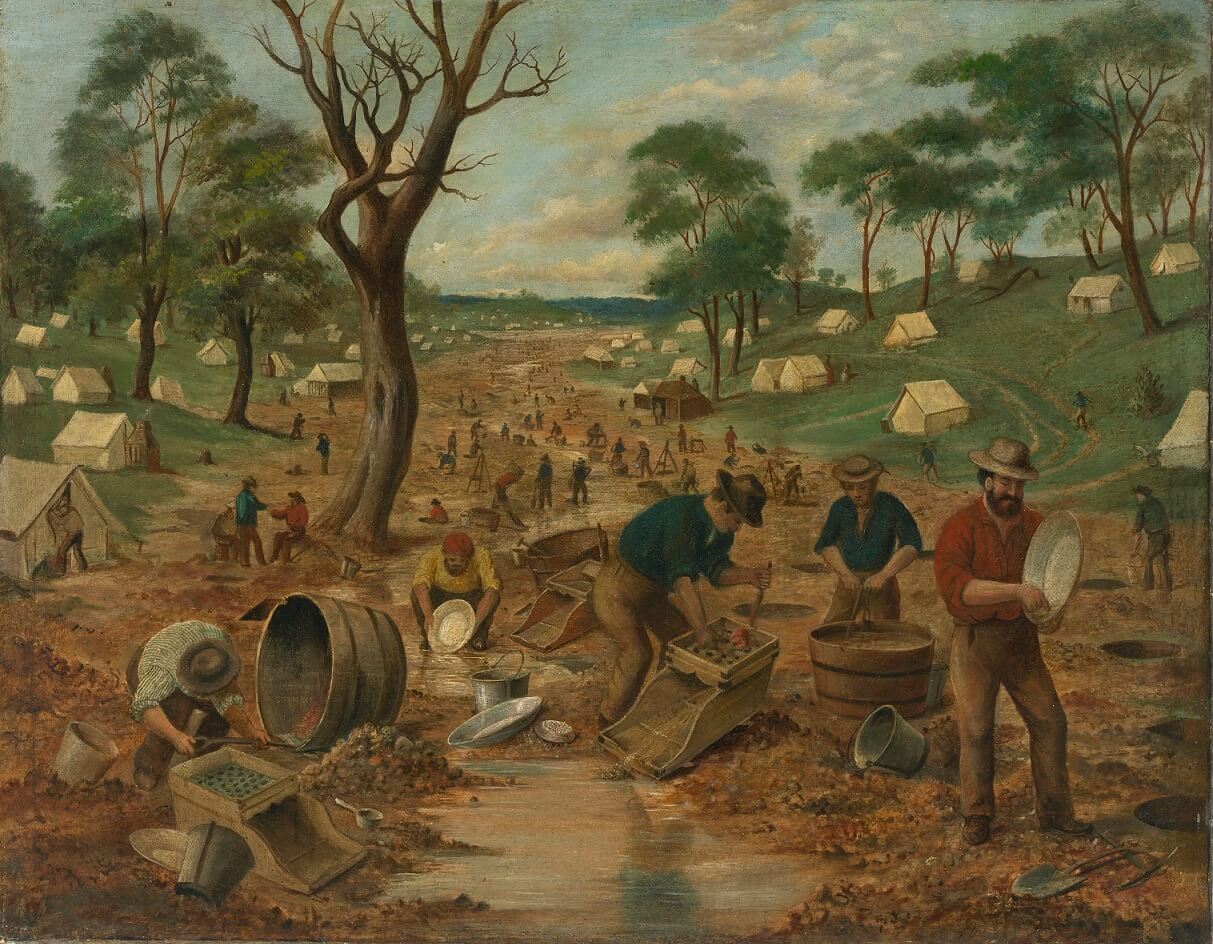

Australian gold diggings by Edwin Stocqueler, c.1855. Courtesy National Library of Australia

[A]dvise him first to go and dig a coal-pit; then work a month at a stone-quarry; next sink a well in the wettest place he can find, of at least fifty feet deep; and finally, clear out a space of sixteen feet square of a bog twenty feet deep; and if, after that he still has a fancy for the gold-fields, let him come.

Author and miner, William Howitt

On the goldfields each digger was allowed only a small ‘claim’ of eight feet square (2.4m) to search for gold.

The digger looked for two kinds of gold - alluvial gold, in the surface soil and the gravel and silt of creek beds, and buried gold, in the deep quartz reefs underground. It was the surface or alluvial gold that started the gold rush. For those who got there first, fortunes were literally lying on the ground. But it was hard work to find it!

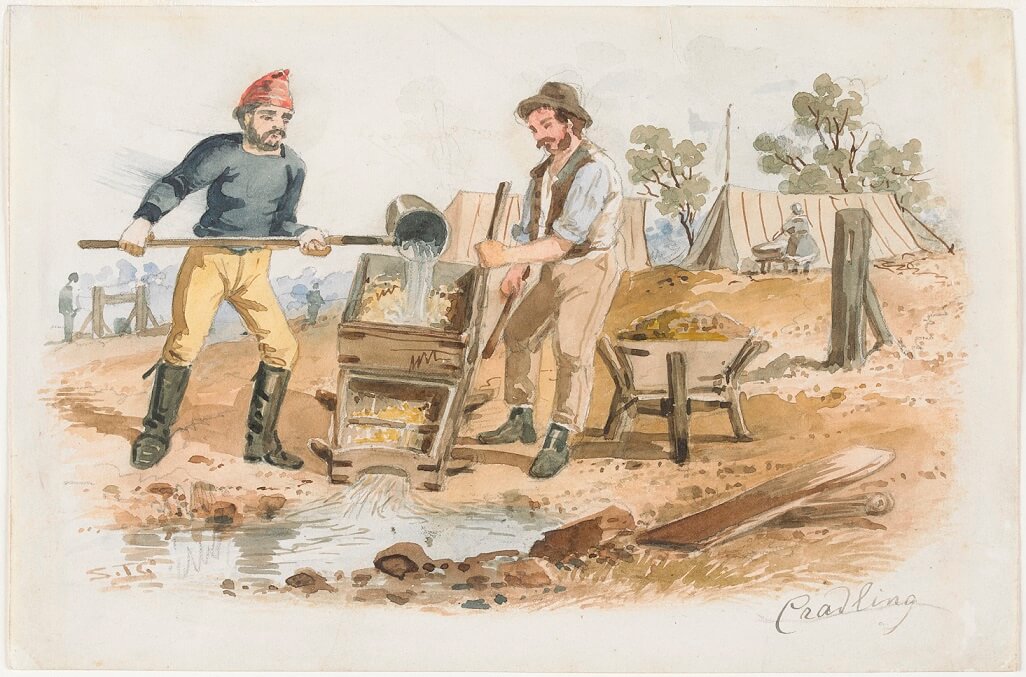

Watercolour by S.T. Gill, 1869, from a sketch completed in the 1850s. Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Mining shallow alluvial gold was straightforward. All you needed was a regular water supply, picks and shovels, pans, and a cradle like the one shown here. The top of the cradle was filled with soil and water, then rocked forcing water and soil through the sieve, leaving any gold behind.

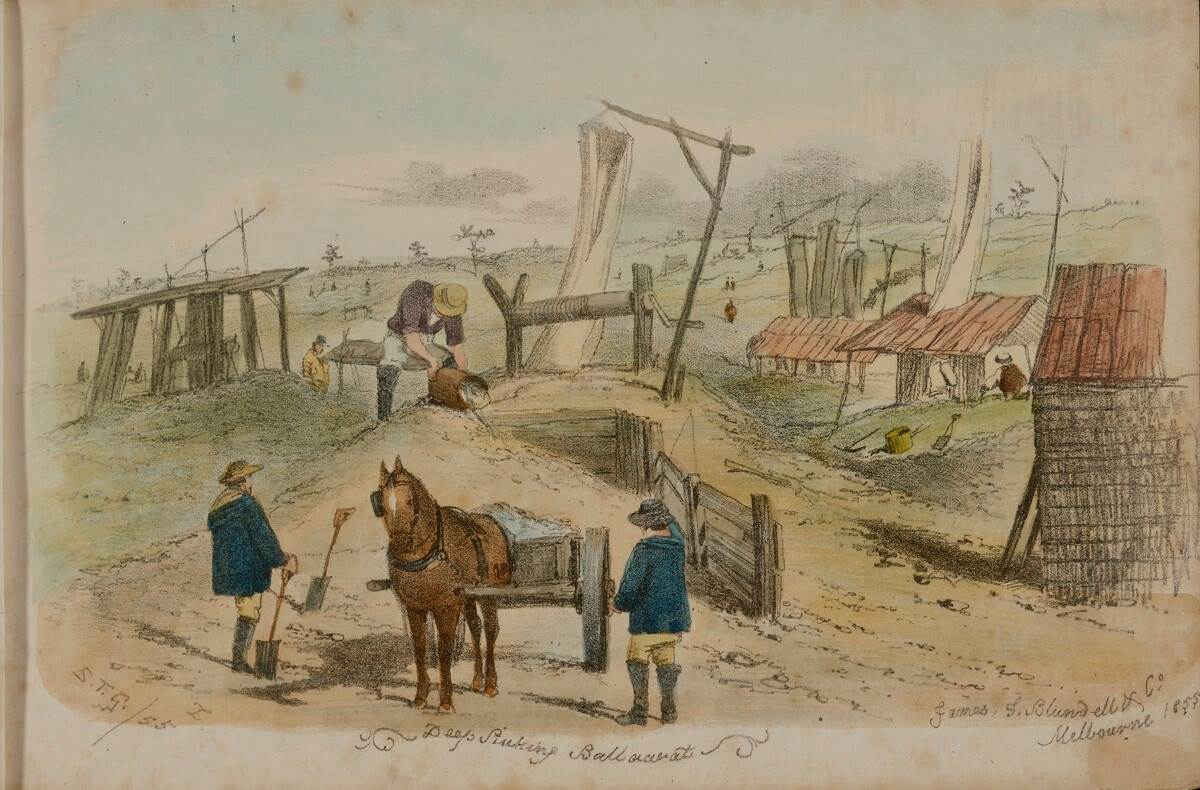

‘Deep sinking, Bakery Hill, Ballaarat, 1853’ by S.T. Gill. Reproduced courtesy National Museum of Australia

When the surface gold ran out, people dug deeper into the ground. They used hand-operated windlasses with buckets on ropes to bring the dirt and gold to the surface. Eventually, the gold was so deep, and in such hard rock, that expensive heavy machinery including rock drills and crushing batteries were needed. By the 1860s most men on the Victorian fields were working for wages, employed by mining companies. They alone could raise sufficient capital to reach the underground gold.

Some spectacular finds

Most gold nuggets were small, weighing only a few ounces each. But every now and then a miner would unearth a spectacular find. At Ballarat in 1858 the ‘Welcome’ nugget was found by a group of Cornish miners in a shaft 55 metres deep. The weight of the nugget was an exceptional 2,217 oz (about 62 kg) - the largest single mass of gold ever found.

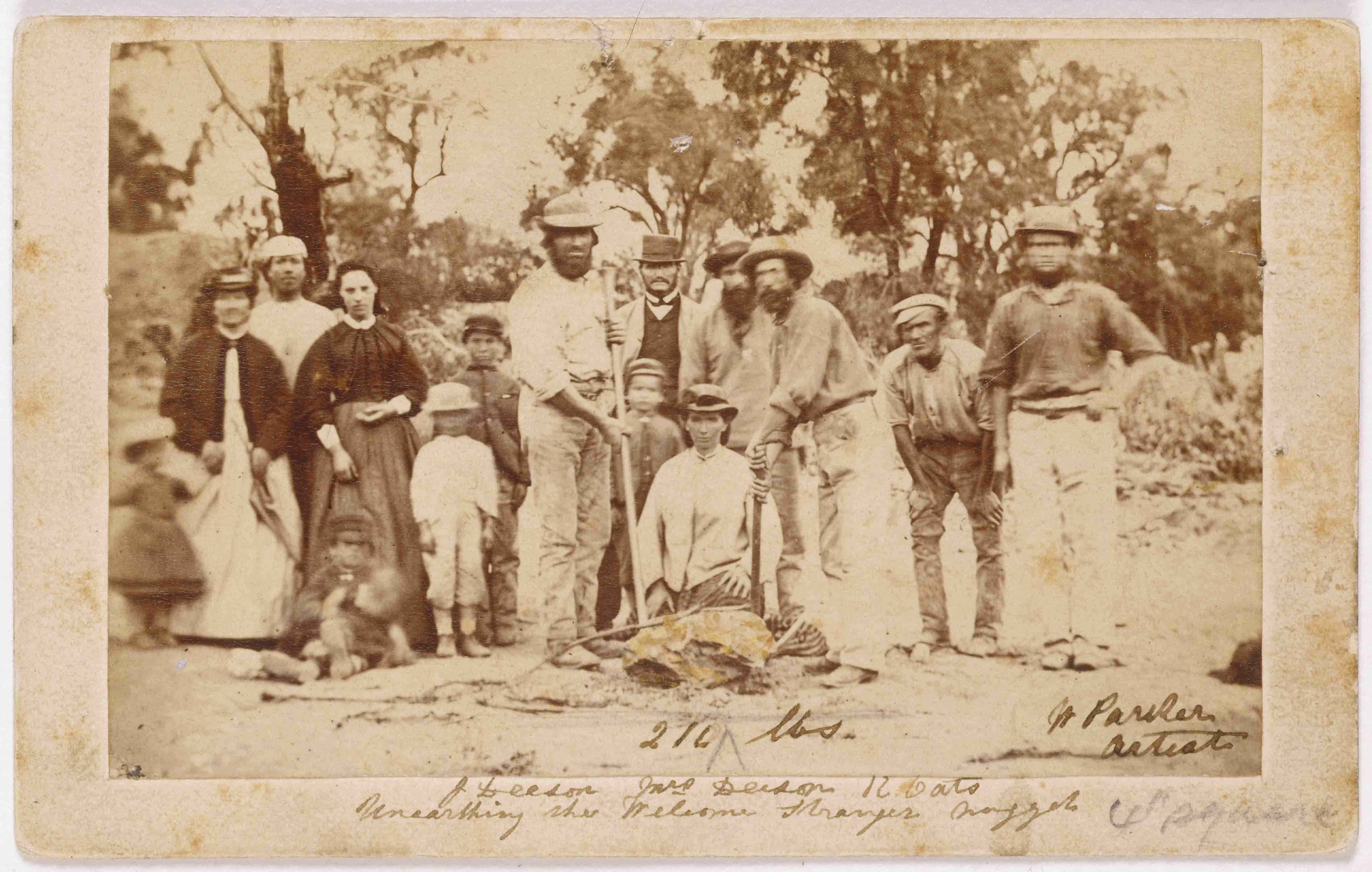

Eleven years later, long after the initial rushes, Cornish miner John Deason and his partner Richard Oates discovered the ‘Welcome Stranger’ near Moliagul in central Victoria. Digging around the roots of a stringybark tree Deason found the gold nugget lying only 3 cm below the surface! After smelting it yielded 2,302 oz (about 71 kg) of solid gold. Deason and Oates shared nearly £10,000 - a fortune indeed in 1869, sufficient to buy eight or ten farms, complete with livestock, fences and buildings.

Photograph by W. Parker. Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Miners and their families posing with the finders of the ‘Welcome Stranger’ nugget, 1869.

The lottery of gold

All diggers dreamt of finding a nugget like the ‘Welcome Stranger’. But few were so lucky. Historians have suggested that perhaps ten per cent of miners made substantial fortunes, another ten per cent made enough to invest in a farm or business, while many just managed to keep themselves. Others found nothing at all. Author and miner William Howitt described gold digging as ‘a lottery, with far more blanks than prizes’.

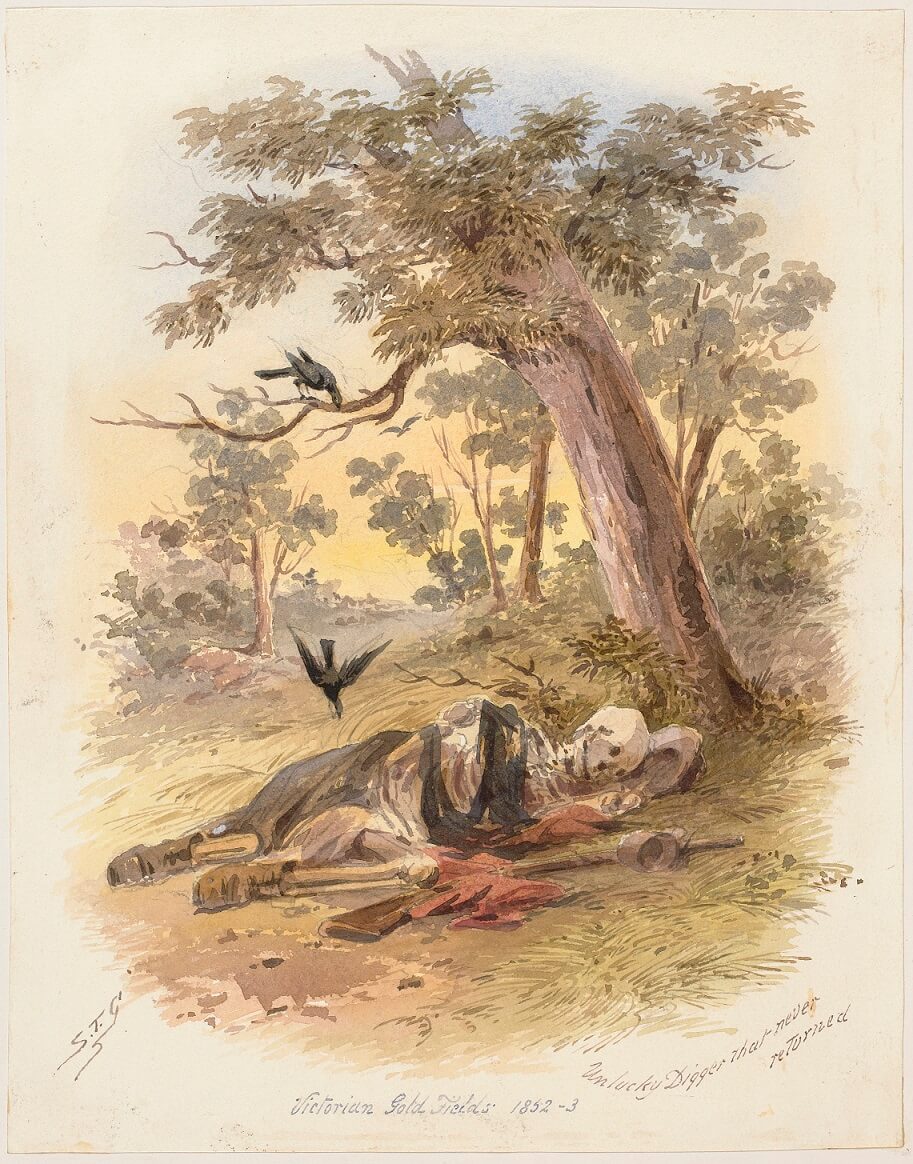

‘The unlucky digger that never returned’ by S.T. Gill, 1869, from a sketch completed in the 1850s. Reproduced Courtesy State Library Victoria

This painting by S.T. Gill shows the skeleton of an unknown digger who died in the bush from starvation or disease and fell prey to scavengers. Other unlucky gold-seekers were seen stumbling in rags along the track back to Melbourne, begging for food or taking whatever menial jobs they could find.

Digging was hard, hazardous, dirty work, with no certain reward. Many gave up in disgust and the numbers leaving the diggings soon equalled those arriving.

Domestic arrangements

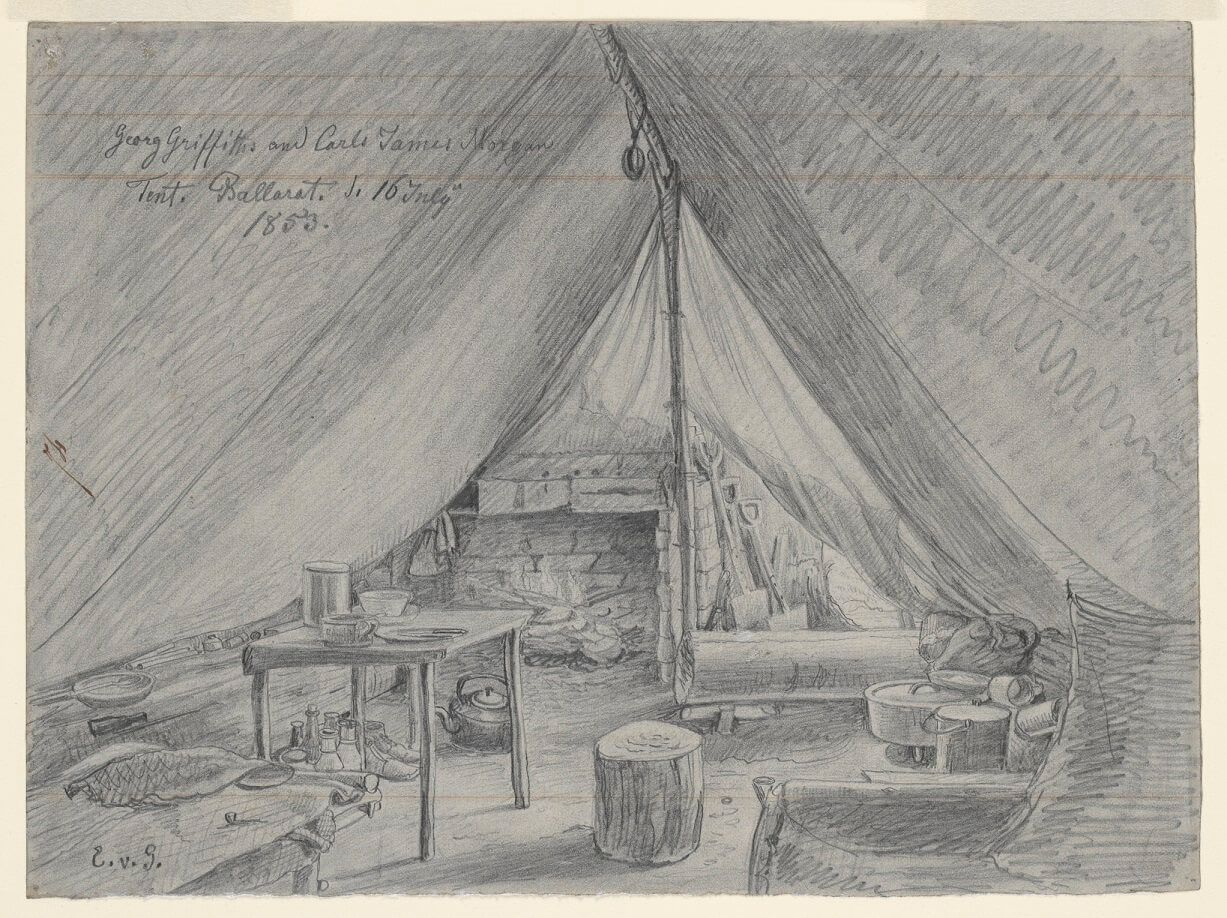

Almost all miners lived in tents - canvas thrown across a timber frame, pegged to the ground, with a dirt floor. Elizabeth Ramsay Laye, a privileged young woman who accompanied her husband to the Castlemaine diggings in about 1853, was horrified by the condition of many of the miners:

… the pale, anxious, haggard appearance of most of the men, tell how dearly bought is the coveted gold. Few of the diggers have beds; a blanket on the bare ground, swarming with fleas, is their only resting place after a hard day’s toil.

Drawing by Eugene von Guérard, 1853. Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

This sketch depicts the primitive nature of goldfields life in the 1850s, although this tent is better equipped than most. There is a fireplace at one end, while a rustic bed, table and log stool serve as furnishings.

A simple diet

A miner’s diet was simple - mainly mutton and ‘duff’, a flour pudding boiled in a bag. Many went without vegetables, even potatoes, for months at a time. Poor diet left diggers prone to all manner of ailments, including scurvy, and hands and knuckles damaged by digging could fester for months.

A dangerous life

The diggings were unhealthy places and mining was dangerous work. ‘Dysentery’, a type of gastroenteritis causing vomiting and diarrhoea, was a constant scourge in the summer, when the streams ran dry and water was scarce and polluted.

Lack of sanitation, the stinking butchers’ tents and slaughter houses all contributed to the spread of disease. The highest mortality rate on the Victorian diggings occurred near Bright in 1854, when more than one thousand miners died from typhoid.

Goldfields were also dangerous places. Death by accident came in many guises - falls down shafts, blows from falling rocks, smothering when shafts collapsed, asphyxiation in tents from charcoal fumes or in shafts from ‘bad air’, blasting accidents, drowning and getting lost in the bush.

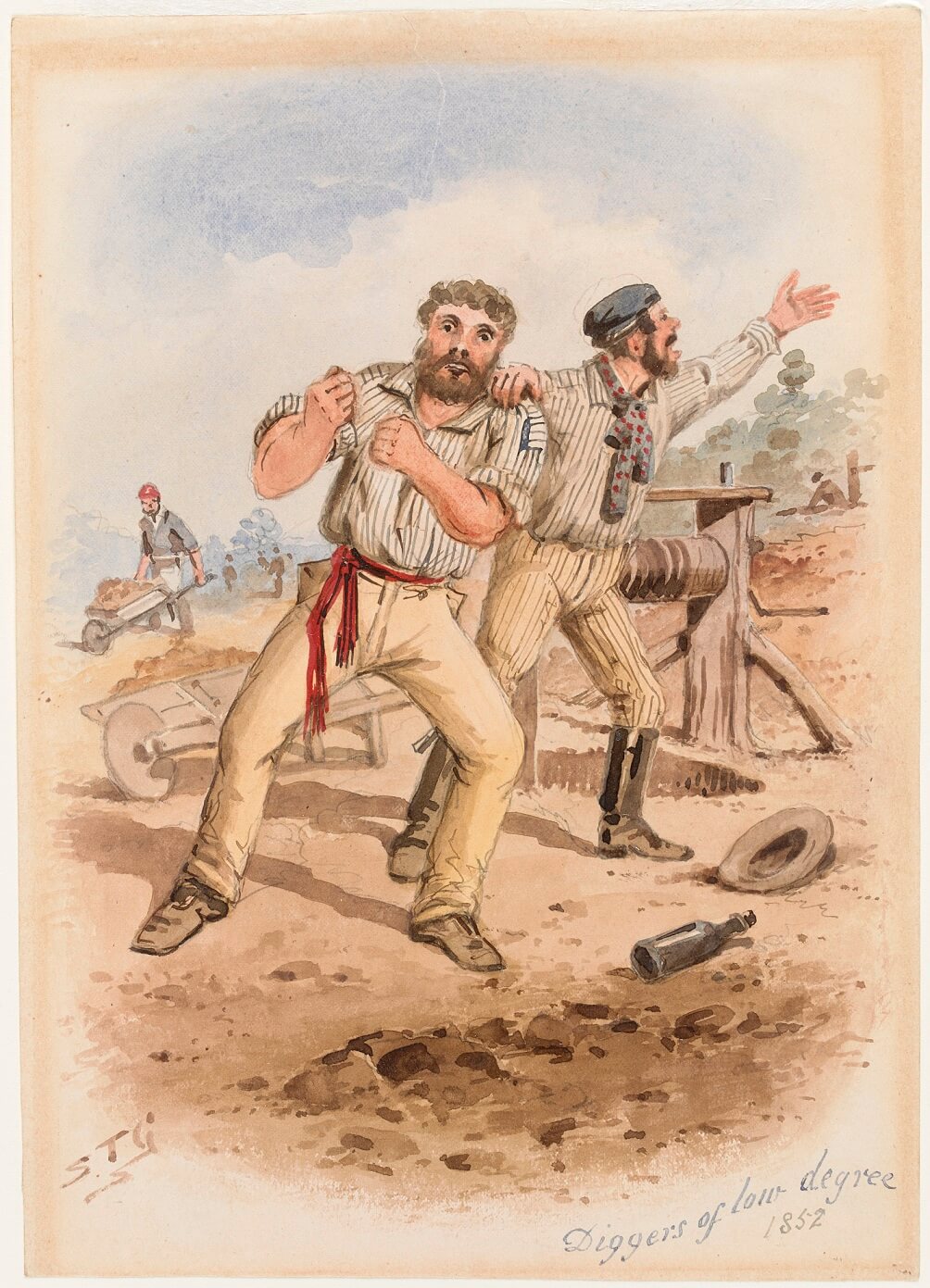

Diggers of low degree 1852 by S.T. Gill. Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Hard work and hard liquor made the goldfields a riotous place. Drunkenness and theft were common, as was ‘claim jumping’ (taking another miner’s claim). Miners sometimes took matters into their own hands. Thieves could be flogged or chained to trees. Historian Geoffrey Serle describes how one thief was doused in sludge, stripped to his underpants, branded with a red-hot chisel ‘Caught Stealing Mates’ Gold’, and banished.

A social life

Mining was hard work, but many diggers had suffered worse as farm labourers, factory workers or convicts.

After the day's labour there was still time to relax by the fire with a drink, a story or song. The hotels, or licensed inns, did a roaring trade, as did (unlicensed) sly-grog shops.

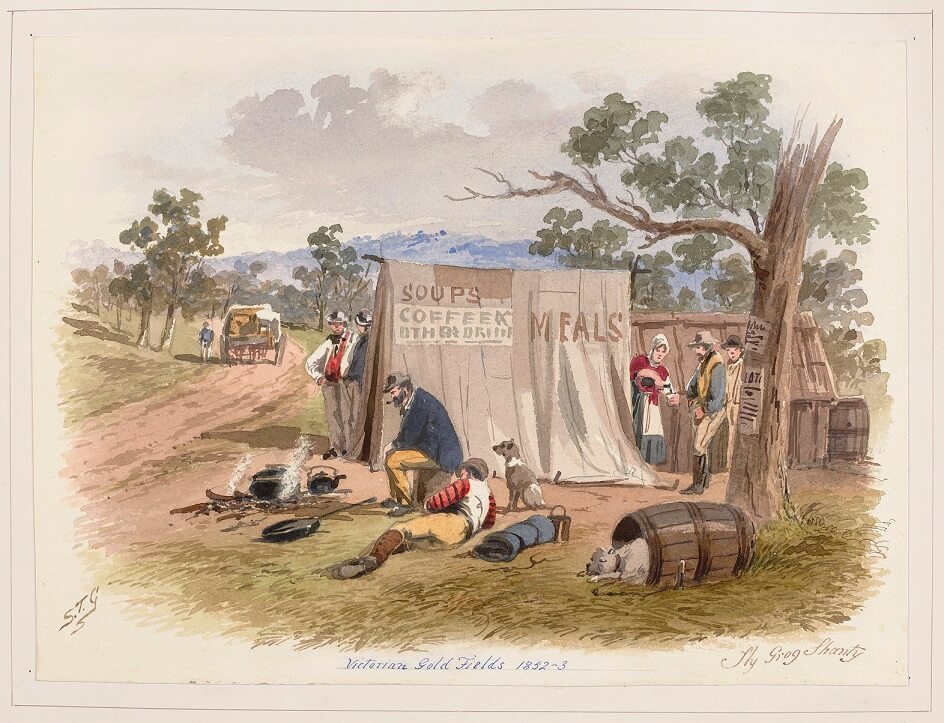

Watercolour by Samuel Thomas Gill, 1869. Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

This image shows a way-side tent selling soup and coffee ‘with other drinks’. Sly grog is available at the rear! Sly-grog selling was illegal, but despite the harsh penalties, shops sprang up all over the diggings, posing as stores and soup kitchens.A woman is shown serving the grog – one of several less respectable occupations for women on the goldfields.

As goldfield towns were established, theatres and concert halls were built, often under canvas. Professional entertainers, such as Charles Thatcher and Lola Montez, toured the goldfields to great acclaim. Lola’s controversial spider dance, with much swirling of skirts and stamping of feet, was a sensation.

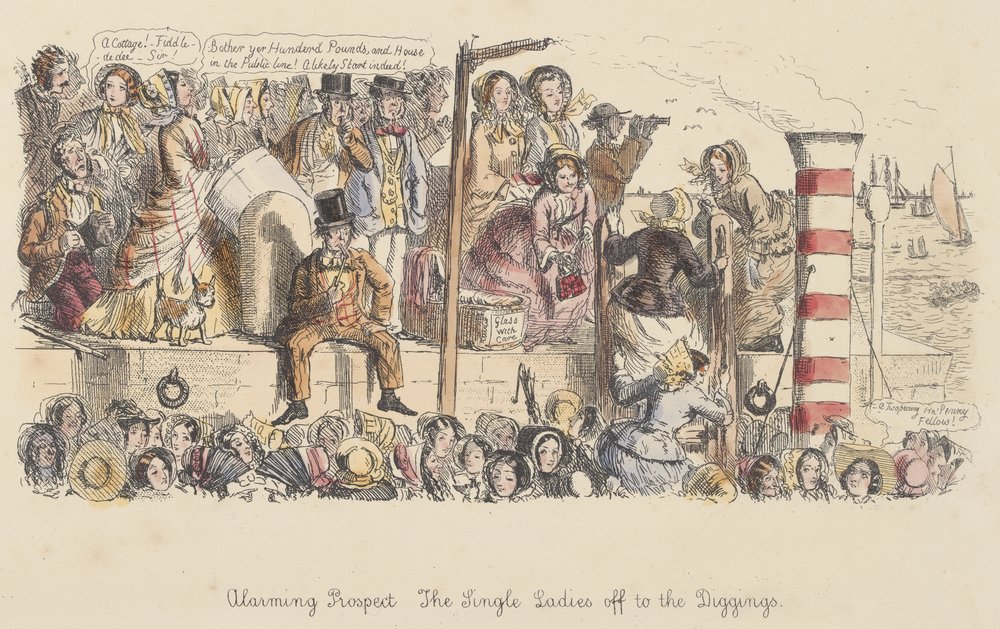

The lure of gold drew thousands of men to the goldfields, leaving jobs and families. Life on the fields was considered unsuitable, especially for ‘respectable’ women, but not for long. By April 1852 The Argus reported ‘At Bendigo, Sheepwash, Emu and Bollock Creeks, there are 15,000 diggers, plus about 10,000 women and children’.

Watercolour by John Leech, 1853. Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

‘Single ladies’ disembarking and heading for the goldfields. The speech bubbles suggest they are seeking husbands with prospects.

Man’s work

… occasionally you will see a woman employed with her clothes held between her knees, rocking a cradle with the untiring energy of a man’.

The Argus, 27 October 1851

The back-breaking labour of gold digging excluded most women, but some worked with their husbands, often washing gold dirt. Others were tempted to fossick, sometimes with spectacular results. Margaret Kennedy, the wife of an overseer, was one of the first to find gold in Bendigo in September 1851.

Sarah Davenport worked alongside her husband, but prospected with ‘another wife’:

… we had not been thair maney days when me and another wife whent a looking around the hills we had each a knife and a tin plate to get goold in if we shold find anny ...i soon picked up a piece about a quarter of an ounce…

Watercolour reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Here Samuel Thomas Gill depicts a family at work. The man pours water into the cradle, the woman rocks it, while nursing a baby. A boy is also working, shovelling dirt. We know that children worked on the goldfields, alongside their parents or in teams with other men. The work was hard for children and could be very dangerous.

Working women

On the goldfields ‘respectable’ women worked as domestic servants, dressmakers, milliners, barmaids and teachers. Less respectable women worked as grog sellers and prostitutes.

Some women set up businesses running tearooms and boarding houses to service the many single men on the fields. One woman who ran a successful business on the Ballarat goldfields was Martha Clendinning. Martha and her sister managed a small shop, selling groceries and baby clothes, largely to women. At Eureka, Phoebe Emerson opened a store to support her ailing husband. She kept a number of dogs for protection and a loaded gun to ‘deter any foolishness’.

Not an easy life

For most women domestic life was a struggle. They had to live in cramped dirty conditions in small tents with few comforts. Poor sanitation and nutrition fostered infections, with little medical attention available. Childbirth was hazardous and infant mortality high. In the 1850s one quarter of all the recorded deaths in Ballarat involved children under five.

The lot of widows, deserted wives and unmarried mothers was especially piteous. Far from family, with no pensions or child support, some women found themselves in desperate poverty.

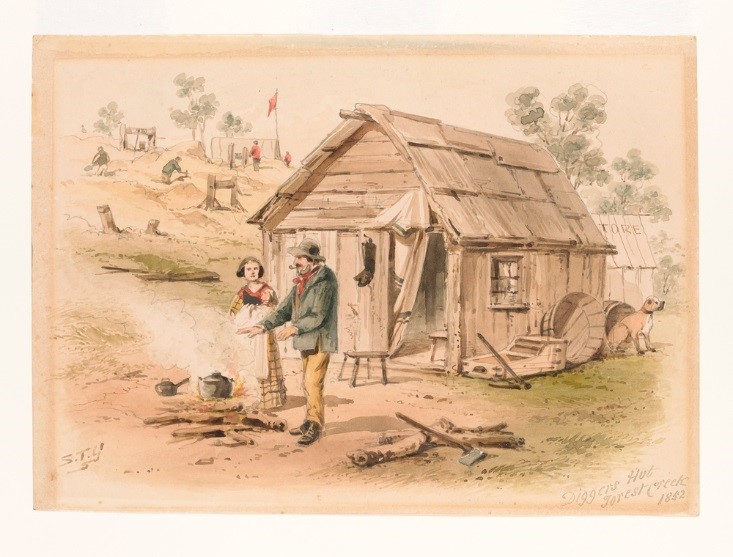

Watercolour by Samuel Thomas Gill, 1872. Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

This digger’s hut is rough, but probably much better than most shelters on the diggings. Conditions were very hard for women, cooking over open fires and with no other facilities.