Bridgetena (Brettena) Smyth (c. 1840-1898) was a well-known figure in late nineteenth-century Melbourne. A woman of commanding stature (she stood nearly six feet tall), she was an eloquent advocate of women’s health education and a committed campaigner for women’s rights. From 1873 she supported herself and her children from a drapery and druggist shop in North Melbourne, but she also lectured regularly on a range of health-related subjects, generally to all-women audiences. From her North Melbourne shop she dispensed contraceptive devices, amongst other more conventional products. Brettena was a committed secularist and an active supporter of the labour movement. Newspaper columnists often described her as a woman of ‘advanced ideas’. Through her lectures and her published works she presented a bold challenge to conventional reticence about reproduction and women’s bodies generally.

Early life

Bridgetena was born in Melbourne in about 1840 (there is some dispute about this date) to Bridgetena and John Riordan, a local merchant. In 1861 she married William Taylor Smyth, who owned a greengrocer’s shop in North Melbourne, and went on to bear five (or perhaps six) children, four of whom survived infancy. William died of tuberculosis in 1873, leaving Brettena to support her three surviving children. Another son had died before adolescence. She promptly converted the greengrocery into a drapery and druggist business, which she managed until shortly before her death.

An early ‘free-thinker’

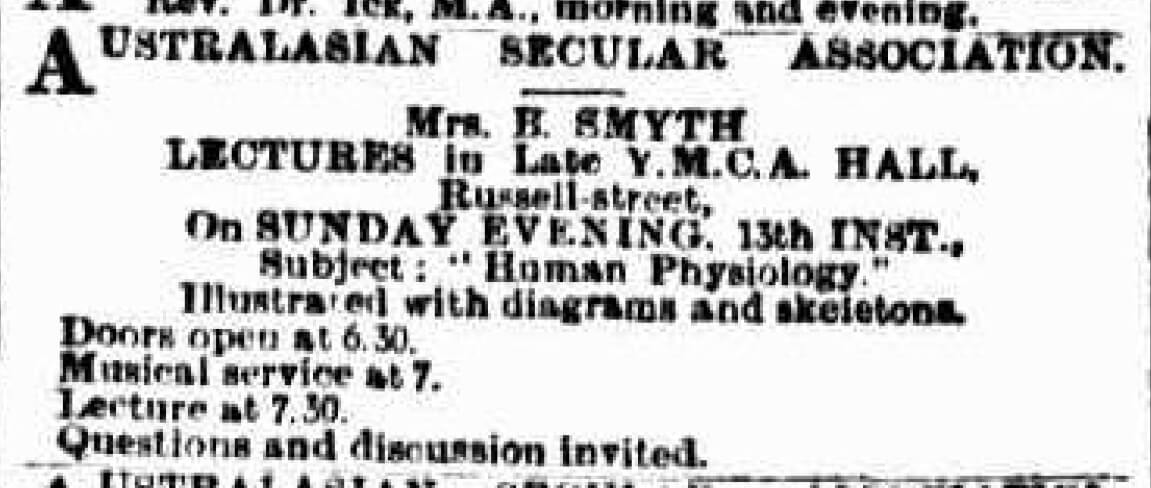

Brettena was an early ‘free-thinker’ – a member of the Eclectic Association and the Australasian Secular Association. The Eclectic Association was formed in the 1870s to discuss ideas considered controversial, while the Australasian Secular Association (ASA, formed in 1882) eschewed organised religion and supported many radical social and political ideas. One of its areas of interest was birth control, or Malthusianism as it was often known – a controversial topic in nineteenth century England and Australia. The National Secular Society in Britain was headed by Charles Bradlaugh, the celebrated atheist MP, who along with Annie Besant, had been prosecuted for obscenity in 1877 for re-publishing a birth control pamphlet – The Fruits of Philosophy, or the Private Companion of Young Married People. Such publications remained open to prosecution in Australia also until late 1888. Indeed attempts were made from time to time to prosecute the ASA for content in its newspaper The Liberator.

Support for women’s suffrage

In addition to her secularism, Brettena was an early supporter of the women’s suffrage movement in Victoria. She was a member of the first suffrage society, the Victorian Women’s Suffrage Society formed in 1884, but in 1888 formed a breakaway group, the Australian Women’s Suffrage Society. Part of the reason seems to have been opposition from members of the Victorian Suffrage Society to Brettena’s outspoken support for voluntary motherhood and effective contraception. Although family size was beginning to decline by the 1880s in Australia, there was great debate about the desirability of smaller families and even greater debate about the means by which the marital birth rate should be controlled. Many suffragists argued for purity and restraint within marriage: others were simply fearful that open advocacy of a controversial issue like birth control would alienate their ‘respectable’ followers and compromise their success in gaining the suffrage. It should be said that no-one (including Brettena) advocated birth control outside of marriage.

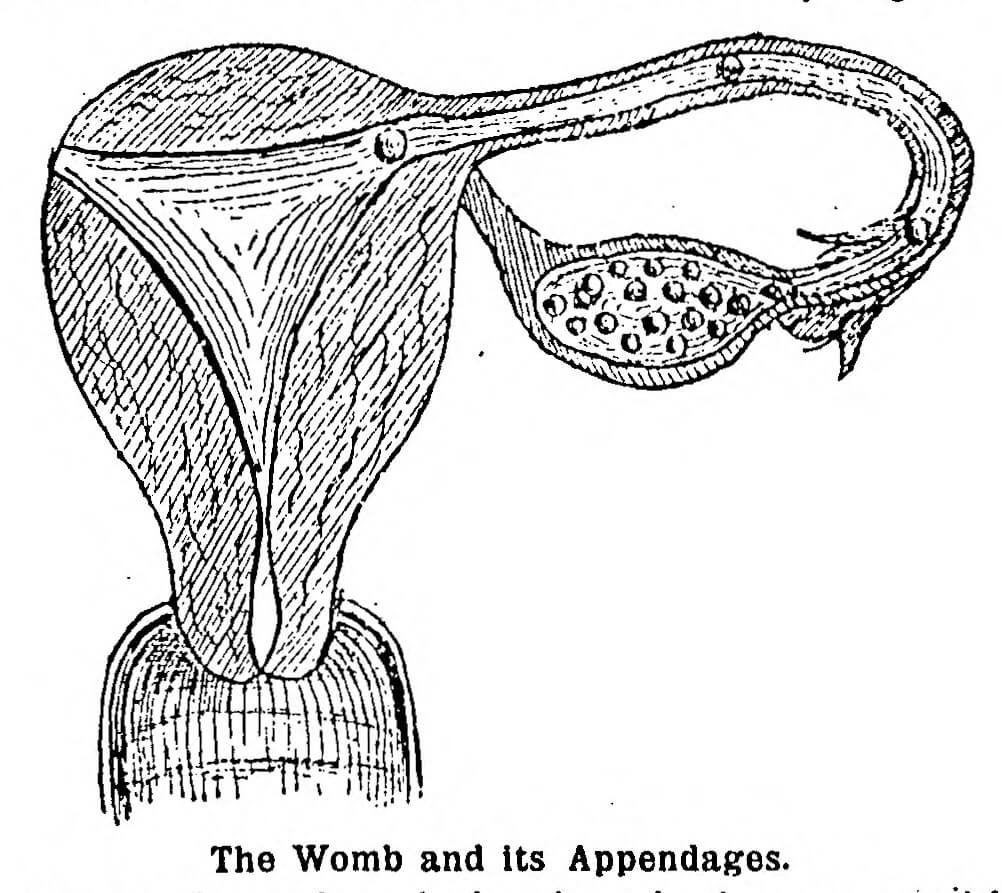

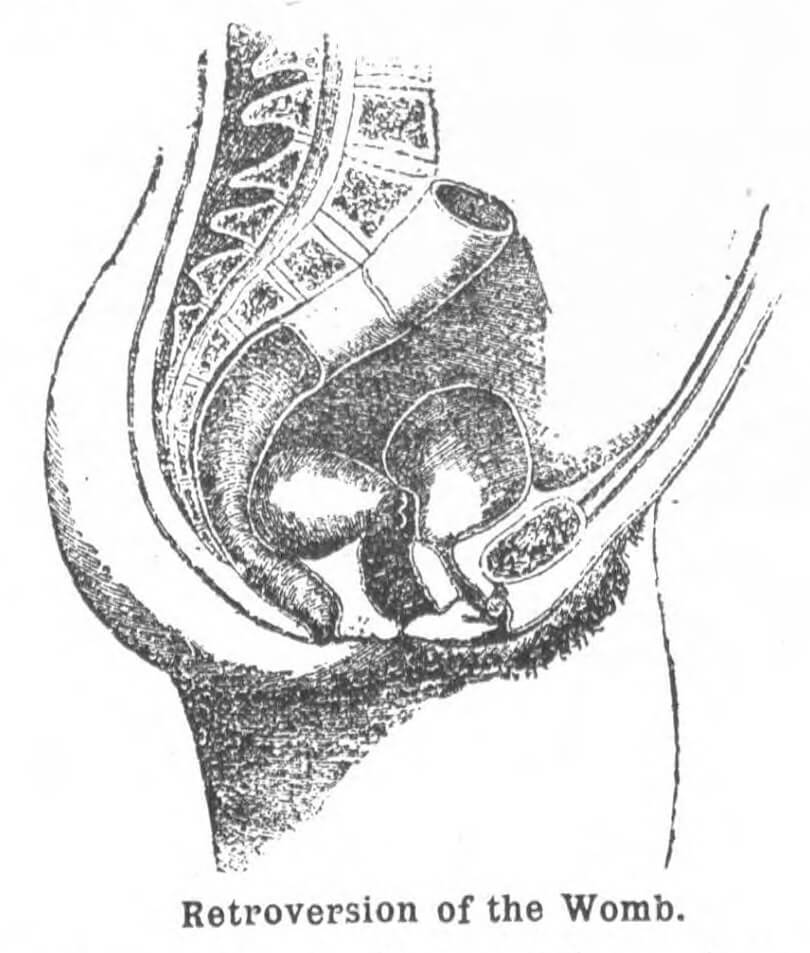

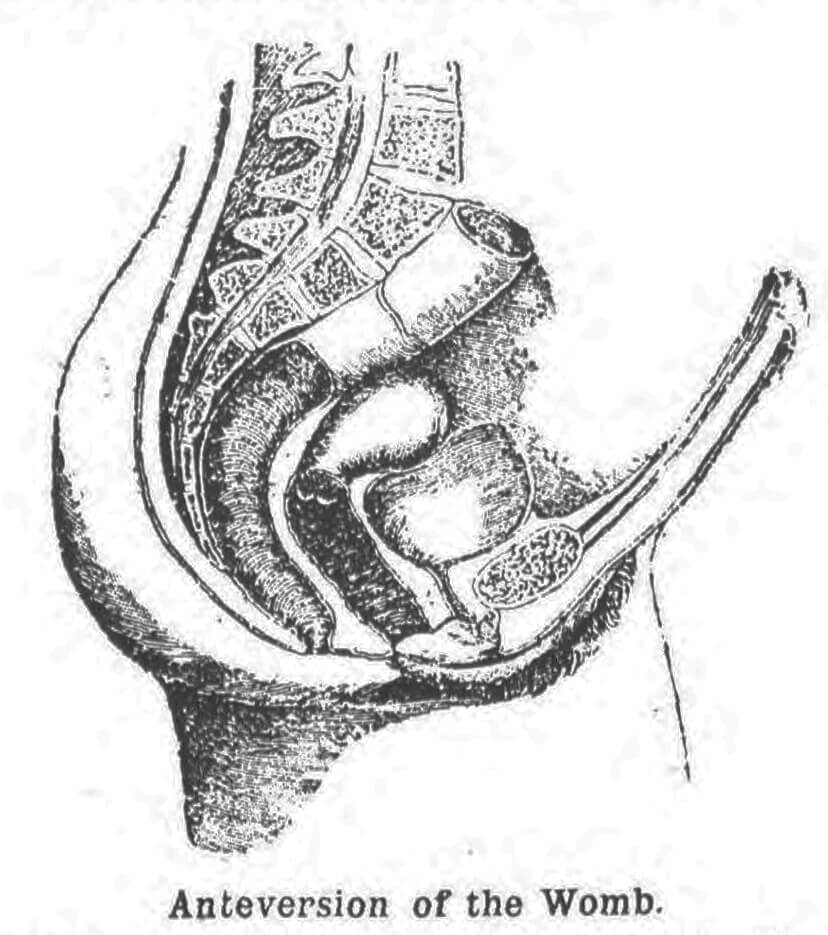

The maternal body

Brettena took a broader view of women’s emancipation than many other feminists at this time. Throughout the nineteenth century motherhood was thought to be the most important role for women, and Brettena often spoke in support of the maternal role. But she deplored the fact that many women were ignorant about the workings of their own bodies, especially their sexual organs. Such topics were widely thought to be indelicate. A small group of determined women set out to change this view, arguing that access to knowledge was crucial for women’s health and for the wider well-being of families. They included early women doctors like Constance Stone, one of the founders of the Queen Victoria Hospital for Women, and others like Brettena Smyth. At one time Brettena had hoped to qualify as a doctor, but university education was expensive and in the wake of the 1890s recession she was unable to complete her studies. She was forced to educate herself as best she could.

An accomplished ‘lecturess’

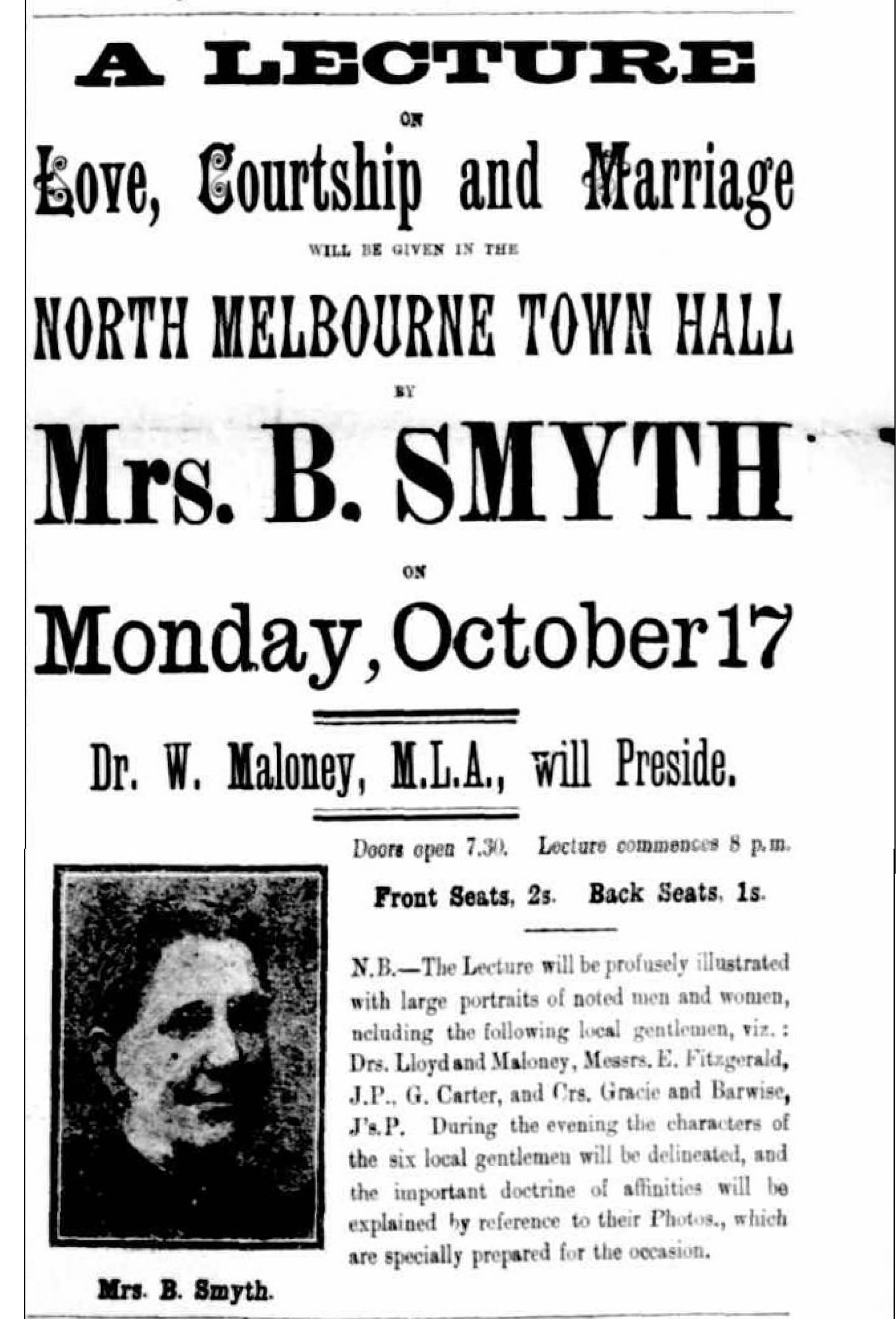

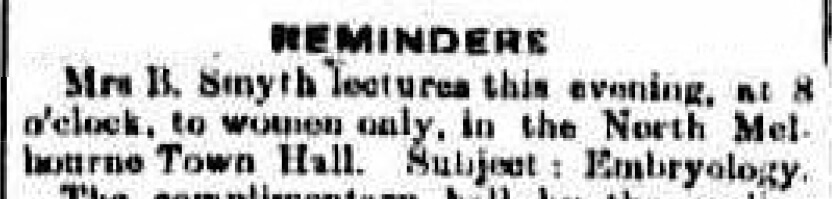

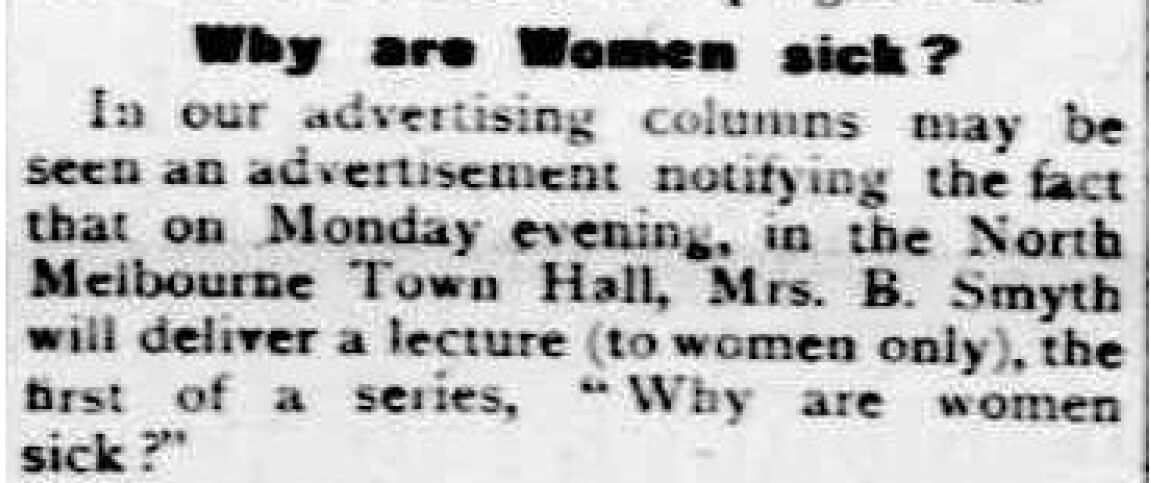

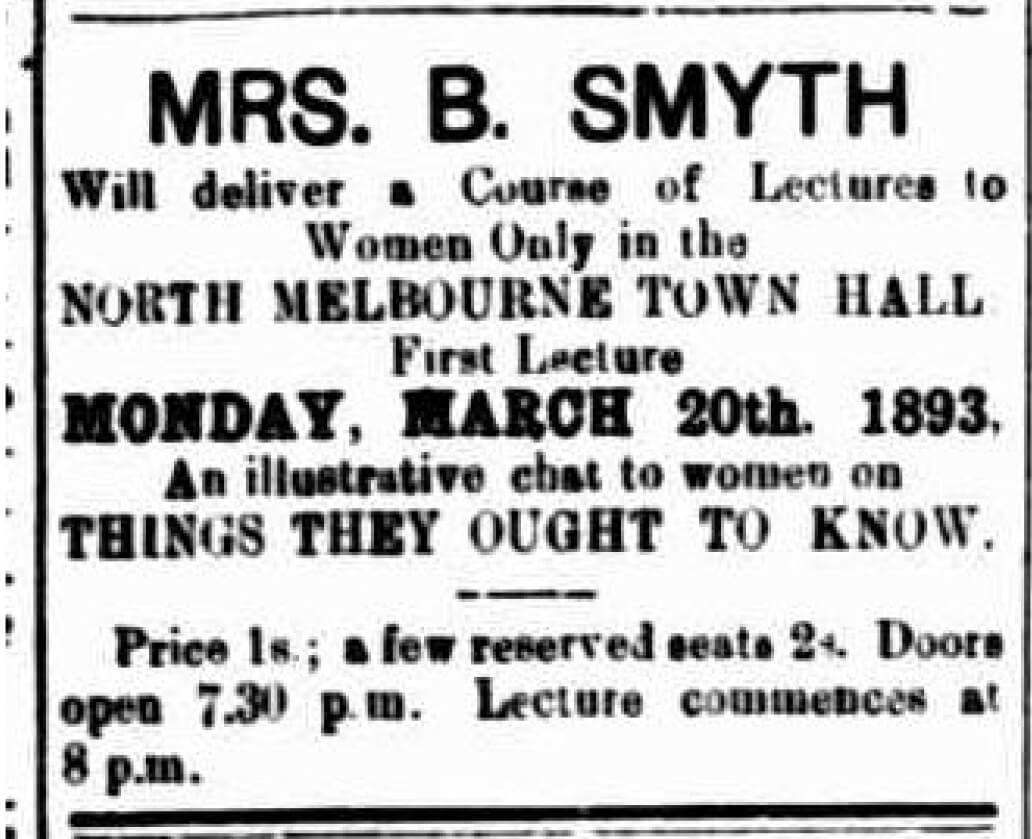

In late 1888 a legal judgement in New South Wales finally overturned a prosecution of birth control literature as ‘obscene’ material, and shortly after this Brettena began to advertise and sell both advice literature and ‘artificial preventives’ - contraceptive devices - from her North Melbourne shop. Her preferred device was the ‘Preventif Pessaire or Contraceptive check- ‘the best, safest and most sure check.’ It was, she argued, ‘the only article of the kind that can be used without the knowledge of the husband.’ She also produced a book, The Diseases of Women, and a range of pamphlets, on topics such as Love, Courtship and Marriage, Woman and How to Train Her, and The Limitation of Offspring. Throughout the 1890s she presented lecture courses on these topics, generally to women-only audiences. From newspaper accounts at the time, they appear to have been well-attended. In October 1892 for example, the North Melbourne Advertiser noted the ‘large audience’ assembled for her lecture on ‘Love, Courtship and Marriage’. The correspondent observed that the lecture ‘contained some very straight advice to the youth of both sexes, and was listened to with sustained attention and interest’. (p. 3)

No false modesty

A similarly ‘large attendance’ greeted the monthly meeting of the Prahran branch of the Women’s Franchise League in July 1895 when Brettena addressed them on the topic ‘Woman, and How to Train Her’. ‘No false modesty should prevent the teaching and education necessary for the ideal commencement of woman’s existence’, she told her audience sternly. ‘Woman should be trained at an early age to understand herself, and should be taught anatomy and physiology and their influence on her life and happiness.’ It was, according to the Prahran Chronicle, an ‘interesting and instructive address.’ (6 July 1895, p. 3)

Social welfare interests

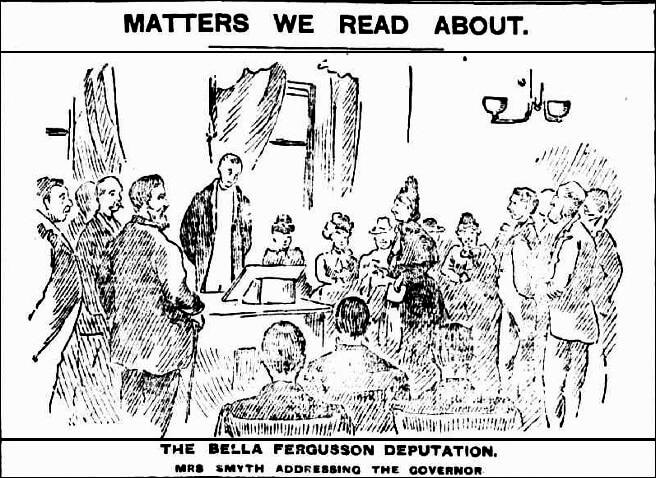

Throughout her public life Brettena Smyth supported a wide range of social and political causes. In 1890 she was named as one of a deputation to the Governor seeking a ‘free pardon’ for Bella Ferguson, a young woman who was convicted of murder after drowning her illegitimate infant in 1889. Although the death sentence had been commuted to 10 years’; imprisonment, the deputation argued that she should be freed, on the basis that ‘the sufferings and pains of maternity, combined with the horror of her position, rendered the prisoner temporarily insane and unaccountable for her actions.’ (Argus, 25 March 1890, p. 9) It was an argument that would be repeated in the case of Maggie Heffernan later in the decade. Mrs Smyth was reported to have ‘offered to take charge of the poor girl in the event of a free pardon’, although it seems that in the end a Mrs Searle actually performed this service. (Bella Ferguson, prison record, PROV, VPRS 516, P2, V10) In reporting the same event the Herald chose to include a line drawing of the meeting, sub-titled ‘The Bella Fergusson {sic} Deputation/ Mrs Smyth Addressing the Governor’. The drawing shows a tall woman, easily matching the height of the male members of the deputation present. (Herald, 25 March 1890, p.1). Portraits of Brettena Smyth are so rare that we decided to include this drawing out of interest.

Support for the unemployed

The depression of the 1890s was one of the worst in Victoria’s history. Thousands were thrown out of work and many were homeless. In the absence of any form of government relief, hunger and destitution were widespread. Parliament responded by cutting back its expenditure, throwing more out of work and actually reducing the funds available to overwhelmed charities. Many in the labour movement were appalled by the distress they saw around them and agitated for the Parliament to take a more active role in assisting the unemployed. A meeting held in North Melbourne Town Hall in March 1894 for example, was chaired by the mayor, and passed a resolution calling on Parliament to resume ‘as soon as possible’, adding: ’That it is absolutely necessary that Government should provide some means of employment for those unable to find work.’ Those who spoke at the meeting emphasised ’that the suffering endured by the working classes was not due to any fault of theirs.’ Brettena also spoke ‘and reminded the audience that working women felt the depression as much as working men.’ (North Melbourne Advertiser, 2 March 1894, p. 2)

Women as citizens

Demands for women’s suffrage intensified in Victoria from the mid-1890s, encouraged by the early examples of New Zealand and South Australia. Brettena spoke regularly at public meetings, in North Melbourne, Brunswick, Fitzroy, Prahran and in regional Victoria. At one ‘noisy’ meeting in Brunswick in June 1894 she was quoted as arguing:

Women should be placed upon the same footing as men, socially and politically, for it was to the advantage of men that women should advance side by side with them with the progress of the age. (Disorder) Many women paid taxes and still had no representation in the Legislature, and this was not fair. (Hear. Hear.) She moved –

That in the opinion of this meeting the women of this colony are justly entitled to the franchise, and that it is a gross injustice to women to withhold it from them; and that the ballot box in their hands would tend to further the best interests of the State.

Despite attempts at disruption from opponents, the motion was carried. (Age, 21 June 1894, p. 6)

The first motion in favour of women’s suffrage was put to the Victorian Parliament in 1889. Regular bills were presented thereafter, and some 19 in total were rejected before women were finally enfranchised in 1908. Victoria was the last Australian state to enfranchise women. The Legislative Council was the main opponent, to the great frustration of the women’s movement and campaigners like Brettena Smyth. In the wake of yet another rejection in 1896 Brettena addressed a public meeting convened in the North Melbourne Town Hall and demanded:

Were the people of Victoria going to submit to the dictates of the Upper House? That august body might trample on men, but they were not going to do it with women. (Applause) There was no true democracy where women were not represented. The Upper House should either be mended or ended. Taxation without representation was tyranny; and from the extension of the franchise to women would also arise social, political, and general benefits. War, drink, the food question, and other complex problems would have additional palliative influences, and clearer solutions brought to bear on them. If a woman was fit to be Queen of the Empire, surely her sisters were fit to vote. (Applause)

In taking the floor Brettena had remarked that she ‘had spoken for many years on that platform on the same subject, and she intended to go on speaking till the Bill was passed’. (North Melbourne Courier and West Melbourne Advertiser, 22 May 1896, p. 2) Sadly that was not to be.

‘One of the most ardent supporters’ of women’s suffrage

On 15 February 1898 Brettena Smyth died from Bright’s disease at her son’s residence in Morwell. She was aged just 57. There were several obituaries in the press, all citing her active support of many social causes and her tireless work for women’s suffrage. The Herald noted that she:

was well known throughout the colonies as one of the most ardent supporters of the women’s suffrage movement. …Mrs Smyth was a fluent speaker and there was not a suburb that she had not visited in order to speak upon the women’s suffrage question. (Herald, 16 February 1898, p. 2)

The Fitzroy City Press regretted the loss of

a lady who for many years was foremost in every good work. To the poor she was a ready friend, and her advanced political views, as well as her personal services as an indefatigable worker in the cause of social reform, is well known to thousands (24 February 1898, p. 3)

Brettena Smyth’s early death ten years before women in Victoria finally achieved the vote probably explains why she is now far less-known than other suffrage campaigners like Vida Goldstein, whose own career as a suffrage leader was only beginning in 1898. But Brettena’s achievements were all the more remarkable for being those of a woman with far fewer privileges – a working woman, who supported her children from the proceeds of her shop, who educated herself and who won widespread respect as a ‘lecturess’ despite (or perhaps because of) her ‘advanced’ social and political ideas. At a time when many feminists shied away from controversial issues like birth control, Brettena saw clearly that women’s emancipation depended on more than access to the ballot box. In her quest for women to understand their bodies and to control reproduction, she was a truly modern woman, far ahead of her time.

Sources

Farley Kelly, ‘Feminism and the Family: Brettena Smyth’, in Eric Fry (ed.) Rebels and Radicals George Allen & Unwin, North Sydney, 1983, pp. 134-47.

Farley Kelly, ‘Smyth, Bridgetena (Brettena) (1840-1898)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Vol 12, Melbourne University Press, 1990. Accessed at: http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/smyth-bridgetena-brettena-8564 June 2019.

Newspaper articles as cited

Further reading

Patricia Grimshaw, Marilyn Lake, Ann McGrath & Marian Quartly Creating a Nation, 1788-1990 Ringwood, McPhee Gribble, 1994

Marilyn Lake Getting Equal: The History of Australian Feminism Sydney, Allen & Unwin, 1999.