Marriage, weddings and the wedding dress

Wedding photographs are now ubiquitous. Literally hundreds of images might be taken of any one ceremony, in both still and moving format, recording the event for posterity in every tiny detail. Earlier generations had only a handful of black and white images, but these often took pride of place on family mantelpieces, gazing at their descendants with the fixed expressions that mark early photographs. Sometimes the wedding photograph might be the only image ever taken of a couple.

Bridal portrait of Mary Phillips and Joseph Solomon, Richmond, 1886

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria (MM110455)

Wedding portraits were rare before the advent of photography, and even then, were often beyond the reach of working families. This bride wears a coloured silk dress, which was common at this time. It is made in the style of the day.

Large wedding party, Bendigo, c. 1905

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria (MM6903)

A large wedding like this was an opportunity for both family and guests to show off their wealth.

All are dressed in the latest fashion, the women with high, boned collars, flounced skirts and large hats; while the men wear either top hats or bowler hats. The groom wears a frock coat with striped trousers.

Studio portrait of wedding party, c. 1910

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

A common style of bridal photography featured the groom seated, with the bride standing to show off her dress. Note that the style of both the bridal dress and the bridesmaid’s dress reflect changing fashions in the pre-war period, with a draped bodice and shortened skirt.

Other souvenirs of the wedding day might be kept too — dried flowers from the bride’s bouquet for example, even pieces of the wedding cake, preserved in tiny tins made for the purpose — while other brides preserved their wedding dresses, carefully stored away as a reminder of the special day that marked the beginning of their family life. One such dress from 1947 is shown in this exhibition.

Worn by Elaine Smith (1926-2015) for her wedding to ex-serviceman Leo Thomas (‘Dick’) Colbert in the Brighton Presbyterian Church. Since fabric was still rationed after the war, Elaine used clothing coupons to purchase the fabric for the dress from Georges Department Store. She designed the dress herself, but had it made by a dressmaker. It was worn with a full-length tulle veil, later sent to England for use by another bride. Elaine carried a bouquet of pink and white hyacinths, grown by her mother, (a keen gardener,) while her sister Mina, as bridesmaid, carried pink hyacinths.

Their reception was held in the church hall next door. Elaine remembered that ‘all the neighbourhood came’. Although she was an accomplished dressmaker,

Elaine bought her going-away outfit from Georges — a mid-blue pleated skirt with matching jacket. The couple spent their wedding night in the Federal Hotel in Melbourne, before setting out for their honeymoon in Mallacoota. Although most brides refashioned their wedding dresses as evening gowns, Elaine preserved hers throughout her life. She and Dick were married for 60 years and had three sons.

An account of their later married life can be found here:

Marriage and the family

Until the late-twentieth century marriage between a man and a woman was the only sanctioned basis of family life in Australia. Marriage and family life in turn were widely regarded as the essential glue that held virtuous societies together, encouraged by a set of moral sanctions that disapproved strongly of sexual relations outside marriage. It is true to say that these applied more strongly to women than to men, but until the late-twentieth century ‘living together’ outside marriage was strongly discouraged. Children born to these unions were initially classed as ‘illegitimate’ and often carried the stigma throughout their lives. Women had other social and economic imperatives in seeking marriage partners too. Single women had less social status than married women and were often figures of ridicule. (The same did not apply to single men.) Women also struggled to support themselves outside a family. Their job opportunities were limited, and they were commonly paid only half the male rate. It was seldom enough to live on. The overall result was that marriage rates were high for both sexes, although at times rather lower for men than women, if sex-ratios were unbalanced during periods of peak migration. The exception to this was the generation affected by the First World War, which claimed the lives of so many young men. Women also tended to marry younger in Australia than they had in Britain, commonly by their early twenties. Throughout the nineteenth century, and into the first decades of the twentieth, children followed promptly on marriage.

Family size

Families in the nineteenth century were large by comparison with those today. In the absence of any reliable form of contraception, groups of eight or nine children were commonplace, while many families were larger than this. The mothers of these families were usually fully occupied in caring for their households, especially where there were no servants to help (the majority). Then in the late-nineteenth century family size began to fall, slowly at first, then accelerating into the twentieth century. By 1900 groups of four or five children were more normal: by the 1930s it was two or three, where it would remain for some decades. Historians have debated the process behind what is known as the ‘first fertility transition’ for many years but it has proved elusive: unfortunately, primary sources that illuminate intimate relations are sparse. Easier access to contraception and better understanding of the process of conception undoubtedly helped from the 1890s, but that is only part of a complex story of changing social attitudes, that slowly shifted concepts of the family to favour smaller groups of children.

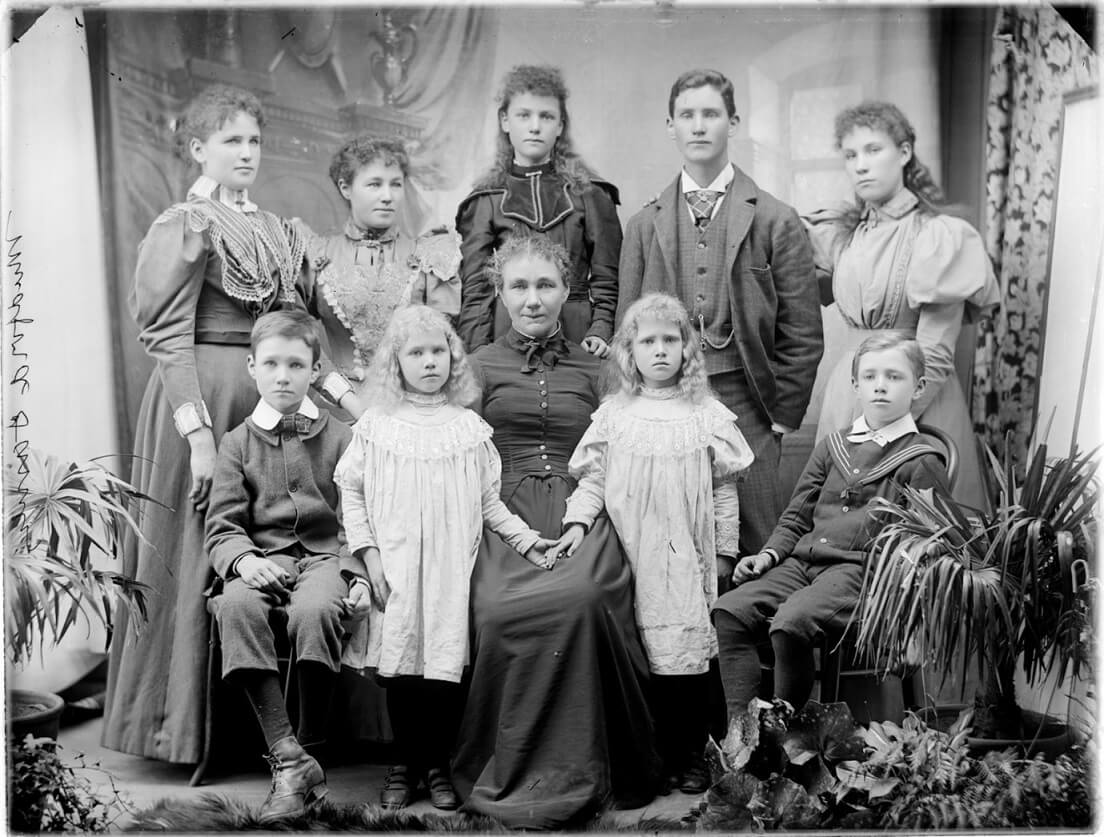

The Mudford family, Kyneton, 1890s

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Families of this size were quite common in the 1890s, although family size was definitely falling by then. Mrs Mudford was pictured with nine children, including twin girls. Caring for a family of this size involved a great deal of work and girls were usually expected to help in the house. Boys often had jobs outside.

Rising age at marriage

The second major period of change in marital patterns in Australia began in the 1970s, reflected in a falling marriage rate and rising age at first marriage. Average age at marriage actually fell for both sexes from 1940 until about 1974 — for men from 26.5 to 23; for women from c. 24 to 21 — but thereafter it rose steadily. In 2019 the median age at first marriage for men was 31 and for women 29, but this partly reflected another major change in relations between the sexes, because by 2019 a majority of couples also lived together before marriage. Estimates suggest that while only about 16 per cent of couples cohabited before marriage in 1975, some 81 per cent did so in 2017. As many as one-third of all children were born out of wedlock by this time, but without the social stigma attached to so-called ‘illegitimate’ births in previous decades.

Family size falls again

The period from the 1960s also saw another change in the family in Australia, this time in its overall size. After reaching a mid-twentieth century high of 3.55 births per woman in 1961, the marital fertility rate (and fertility in general) fell steadily and was below replacement level (officially assumed to be 2.1 births per woman) from 1976. Australia’s fertility rate reached its lowest level ever in 2020, in the midst of the COVID pandemic, when it fell to only 1.58, but recovered to 1.7 in 2021. Women not only bore fewer children in the early-twenty-first century, they also gave birth much later than in previous generations. In 1981 only 15 per cent of first mothers were aged over 30. By 2019 over half had their first child in their thirties, while 17 per cent were aged over 35 (an increase from 5 per cent in 1991). Teenage mothers virtually disappeared, falling from 17 per cent in 1961 to only 4 per cent in 2019, as access to the contraceptive pill, and legalized abortion, removed the social pressure for early marriage, and the heartbreak of enforced adoption.

Who could marry?

Another significant change in attitudes to family life came with the increased acceptance of same-sex couples from the 1980s, but there was still great debate about whether such couples might legally marry. Although marriage was assumed to be the union of a man and a woman, it was not so defined in law. The Family Law Act of 1975 for example referred to marriage as ‘the union of 2 people to the exclusion of all others voluntarily entered into for life.’ (S 43 (1) (a). As pressure to recognise same-sex marriage increased in the early years of this century, the conservative Howard Federal Government introduced an amendment to the Federal Marriage Act which unequivocally defined marriage as ‘the union of a man and a woman’ and provided that same-sex marriages entered into under the law of another country would not be recognized in Australia (Marriage Amendment Bill, 2004, summary). After 22 failed attempts, this amendment was finally overturned in 2017, when same-sex marriage was legalised, after a voluntary postal vote confirmed that a clear majority of Australians favoured change.

Kath Brackett and Anissa Thompson embrace after a wedding ceremony on their front lawn during the COVID lockdown, 23 May 2020. Photographer: Julie Ewing

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria. (MM153204)

The year 2017 saw a revolutionary change in the definition of marriage in Australia with the legalisation of same-sex marriage. There was a rush of same-sex ceremonies very soon afterwards. Other couples chose to wait for a significant date. May 2020 marked the twentieth anniversary of Kath and Anissa’s relationship, and they decided to go ahead with a ceremony despite lockdown restrictions.

Collected as part of the ‘Museum In My Neighbourhood Project’ with support from the Office of Suburban Development

‘Till death us do part’

At first marriage was, literally, a contract for life — ‘till death us do part’ as it said in the Church of England’s Book of Common Prayer. Marriage was, and remains, a verbal contract between the two consenting parties, (hence the need for witnesses,) and this was one of the promises they made to each other during the marriage ceremony. Setting that promise aside, through annulment or divorce, was at first extremely difficult and certainly far beyond the means of ordinary people. Before the first divorce laws were passed in the mid-nineteenth century, marriages could only be dissolved by the ecclesiastical courts in England and Wales, since the Church considered marriage to be a sacrament. This entailed lengthy and complex proceedings and often a private Act of the British Parliament, obtainable only at vast expense and with notable public scandal.

The Divorce & Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857 made it possible to institute divorce in a civil proceeding, and similar acts were subsequently passed in each of the Australian colonies, including Victoria in 1861. The grounds on which couples were entitled to divorce were at first very unequal. Although they could obtain a legal separation on equal grounds (judicial separation), the different moral standards applied to the sexes meant that a man could obtain a divorce simply on the grounds of his wife’s adultery, while a wife had to prove adultery coupled with incest, bigamy, cruelty, or desertion ‘without reasonable excuse’ for two years or more (Marriage & Matrimonial Causes Statute 1861 (Vict) sections V & XIII). Different state laws regulated divorce until early 1961, when the Commonwealth Government’s Matrimonial Causes Act,1959 came into operation. This allowed for divorce simply on the grounds of separation for five years or more (amongst other grounds), but it was not until the passage of the Family Law Act, 1975 (Cwlth) that so-called ‘no-fault divorce’ was established. The number of divorces rose steadily from the mid-twentieth century, with a peak just after the introduction of the Family Law Act in 1976. The risk of any marriage ending in divorce plateaued at about 40 per cent in the 1980s and nineties but declined as age at marriage rose. Perhaps one in three marriages currently ends in divorce.

The wedding

These were profound changes in the nature, size, and shape of the Australian family. And yet there were some remarkable continuities. Although marriage rates declined as age at marriage rose, many people still chose to marry eventually, and that meant a ceremony of some sort, even if it was the minimum possible. Surprisingly, it turns out that ‘the wedding’ has proved more resistant to change than marriage itself.

Many people today think that a ‘traditional’ wedding involves a bride in a long white dress, perhaps wearing a veil and carrying a bouquet of flowers. But this is a relatively recent practice. In the nineteenth century, most brides did not wear white: they simply wore their best dress, usually in a coloured fabric that was the best they could afford. Wealthy brides wore silk: others either cotton or wool, depending on the season. And the wedding itself generally took place in the morning, (8 or 9 am seems to have been common,) sometimes with a wedding ‘breakfast’ to follow, if the family was prosperous enough. This was because most marriages took place in a church and since the Church of England and the Roman Catholic Church regarded marriage as a sacrament, those participating were expected to fast beforehand. After taking Holy Communion, the couple could break their fast. Later the term ‘wedding breakfast’ seems to have referred to a meal served at any time after the wedding, but at first, it was just that — a breakfast, although often with a cake.

The ‘white wedding’

There is a general consensus that the fashion for white wedding dresses followed the example of Queen Victoria, who wore ivory satin when she married Prince Albert in February 1840. Illustrations of the wedding circulated widely and encouraged the wealthy to follow suit. The wedding of Prince Albert to Princess Alexandra of Denmark in 1863 was publicised even more widely and she was the first royal bride to be photographed wearing her wedding dress. The dress itself, preserved in the Royal Collection, was white silk satin, trimmed with orange blossom, tulle, and Honiton lace, with a matching veil and a long silver moiré train. The skirt had four deep lace flounces, in the fashion of the day. Nevertheless, it took some time for the fashion for white wedding dresses to catch on. White was not a practical colour for dresses and it was rare for any bride to commission a dress to be worn only once. For a long time that seemed a scandalous expense: even Queen Victoria recycled her wedding dress, though clearly Queen Alexandra did not. Nor did Elaine Colbert, (née Smith) whose cream satin wedding dress from 1947 is featured in this exhibition. My own mother, who married in 1950, had her ivory satin wedding dress remodeled into an evening dress, with a deep burgundy bodice. Sadly, it did not survive the ministrations of two small girls using it for ‘dressing up’ some years later!

At some point during the later decades of the nineteenth century, as ‘traditions’ surrounding the wedding were developed and popularised, it was suggested that wearing white symbolized a bride’s innocence and purity (meaning virginity). These ‘traditions’ were of recent invention, but they took firm hold by the turn of the twentieth century.[i] The entire question of bridal innocence is itself complex, since there was a very high rate of bridal pregnancy in earlier centuries, sometimes reflecting older customs of ‘handfasting’, or formal betrothal, which sanctioned sexual activity; and sometimes reflecting differences between the customs of the wealthy or middle class and those of ordinary folk. Some simply decided to formalize a relationship when a woman became pregnant: others did not bother at all! Estimates of bridal pregnancy in nineteenth-century Australia suggest that somewhere between 18 and 35 per cent of brides were probably pregnant on marriage, (the broad estimate reflects the findings reported from different demographic samples,) while rates of illegitimacy may have been as high as 20 per cent of all live births at times.[ii]

Studio portrait of Ada Blakely (née Gibson) on her wedding day, 12 May 1937

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria (MM123326)

By the 1930s hems had descended again and dresses hugged the body, though the shape of the headpiece and veil is still reminiscent of the 1920s. Ada Gibson was a talented pianist and church organist. She married manufacturer William Blakely in the Congregational Church, Windsor and they went to live in Brighton.

Bridal party of June Burr & Ernest Lee, 2 November 1944

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

This wartime wedding shows the ingenuity of couples faced with wartime shortages and brief periods of leave. Ernest was serving in the RAAF in Darwin, while June was with the Australian Women’s Army Service. The family was not well off. June made her dress herself using mosquito netting, which was not rationed. They married in the Tyler Street Methodist Church, Preston. The dress is preserved in the Museums Victoria collection (HT49674).

Marriage of Helen Fotopoulos and George Retsis in Greek Orthodox Church, Carlton North, 1959

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria (MM110557)

The bride’s dress reflects the full skirts of the post-war ‘New Look’, first launched by Christian Dior in 1947 and popular throughout the 1950s. This marriage was solemnised according to the rites of the Greek Orthodox Church. Both bride and groom wear traditional Stefana (wedding crowns), which were blessed by the priest during the ceremony, and symbolised the fact that the man and woman were the ‘king’ and ‘queen’ of their home. Until about 1970 most couples were married by a minister of religion. By the year 2000 half of all weddings were conducted by civil celebrants and by 2019 this had reached 80 per cent.

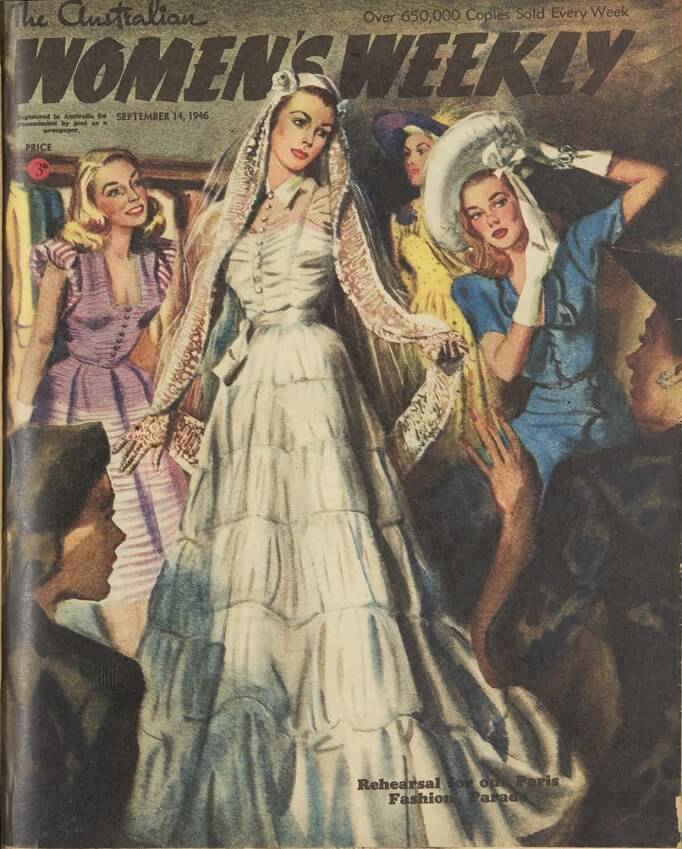

The role of the press

By the late-nineteenth century the weddings of the wealthy were often described in detail in the local press. Such descriptions helped to cement more general expectations of the ‘proper’ wedding, supported by the appearance of advice manuals that purported to guide the uninitiated in appropriate ‘etiquette’ for both dress and behaviour. When Ethel Clarke, daughter of Sir Rupert Clarke of Rupertswood, married George Cruikshank in April 1895, the Argus described the proceedings in detail, though the fashion conscious might have decried the absence of a detailed description of Miss Clarke’s dress. Readers were informed only that her ‘bridal dress’ was ‘of pure white’, while those of her attendants ‘in their white hats and dresses splashed with pink and blue, harmonized well with the bouquets that they carried’. The focus of the Argus correspondent was more on the number of prominent people there, than on the appearance of the bride. It was left to the Bishop of Melbourne to pay tribute to ‘the beauty of the bride, the evident happiness of the bridegroom and the misfortune which Victoria has sustained in allowing one of the brightest jewels of her womanhood to be taken away to the neighbouring colony’ (George Cruikshank was a NSW MP). (19 April 1895, p. 6.)

There was no such shortcoming in the account of the wedding of Mary Chirnside to Everard Browne at Werribee in September 1894. The Australasian’s correspondent ‘Queen Bee’ gave detailed descriptions of the bridal dress, those of her attendants, and finally the outfits of the more prominent women amongst the guests. The apparel of the men merited only the briefest reference. ‘Queen Bee’s’ description of the spectacle, for spectacle it undoubtedly was, can be accessed here: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/138598709?searchTerm=The%20Werribee%20Wedding

Perhaps Miss Chirnside was no great beauty, for Queen Bee described her instead as looking ‘handsome and graceful’, as she entered the church on her brother’s arm, wearing her:

rich and beautiful bridal gown of ivory-white satin duchesse, trimmed with Brussels lace in festoons on the skirt. The same lace was draped on the bodice to form a picturesque fichu, which was caught on one side with a trail and bouquet of orange blossoms. The long court train of satin was trimmed with a wide rever of Brussels lace and caught up with a bouquet of orange blossom. Wreath of the same flowers and a veil of the finest Brussels net covered her completely, falling over her face and reaching the end of her train. The bridegroom’s gift, a diamond crescent, was worn in the hair. (Australasian, 15 September 1894, p.34.)

There was a great deal more, describing the decorations, the presents (including those from Lord and Lady Hopetoun in advance of their arrival in the Colony) and listing the most important guests. The account filled a full page of newsprint. Here then, was the society wedding par excellence! Wedding photographs preserved from the period, suggest that it was becoming the model that the prosperous sought to emulate.

Child’s play

Toys also played a role in shaping little girls’ ideas about weddings. Bride dolls were produced from the late-nineteenth century, although most were expensive toys, aimed at wealthy children. One of the earliest bride dolls (illustrated below) is found in the collection of the Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences. It dates from the 1880s and is beautifully dressed in a hand-sewn costume, with a full set of underwear beneath. The bodice and skirt of the dress is made of cream silk satin. Another early bride doll is a beautiful bisque doll in the collection of Te Papa, shown here. It was probably made in the 1890s or 1900s, although the dress style suggests that the clothing dates from the later period. Dolls like these were imported from England and Germany into both New Zealand and Australia before the First World War. It seems clear from newspaper advertisements and other snippets that the ‘bride doll’ was an established category of doll by the 1900s. In 1910, when the Lady Maryoress of Malvern organized a doll exhibition as a Christmas fund-raiser for the Children’s Hospital, ‘Queen Bee’ of the Australasian reported the event at length. Prizes were given for the best-dressed dolls. Included in the commentary was the observation:

Satin-clad bride dolls were many, and the handsomest of these was from Mrs. Tom Hogan. The second most elaborate one was the work of Miss Cox, a schoolgirl of thirteen, who was awarded second prize. The fit and make of the dress and the general aspect of the doll was quite professional.

Australasian, 10 December 1910, p. 48

Bride doll, wax head and cloth body, c. 1880s

Reproduced courtesy Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences (H8140/8)

This doll was probably made by the Pierotti family in London. It was an expensive toy. The clothes are hand-sewn and elaborate, with three petticoats and a pair of drawers. The dress is of cream silk satin, with cotton lace trim and cotton lining.

Bride doll, 1891-1910, Germany, by Simon & Halbig. Gift of Mrs A Hill, date unknown. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Te Papa (PC001007)

Reproduced courtesy Te Papa

Dolls like this helped to form the expectations of little girls in wealthy families. The doll’s head is made of bisque porcelain, tinted to make it more realistic. The body parts were made in another factory and were probably of leather or cloth. The doll is dressed in a style reminiscent of about 1910.

Rising living standards in the post-Second World War period meant that dolls, including bride dolls, were available to far more children. The use of celluloid in doll manufacture also helped. Some of these dolls were made locally, including the two dolls in Museums Victoria’s collection, made by Melbourne company L J Sterne. Many little girls owned bride dolls in the 1950s and sixties, along with dresses and veils, increasingly made in the new synthetic fabrics (including nylon). Bride dolls continued to be made in the 1970s, but thereafter were less popular, reflecting changing ideas about woman’s place.

Bride dolls, L J Sterne Doll Co., Melbourne, c. 1950 (MM132367)

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria

These dolls were manufactured by the L J Sterne Doll Company (1939-71), a Melbourne company formed by Austrian migrants Leo and Hilda Sterne. The dolls are dressed as brides. Bride dolls were very popular in the post-war period and helped shape girls’ expectations of marriage and weddings.

Dressed à la mode

However much they appealed to bridal ‘traditions’ in other matters, brides in the late-nineteenth century and for many decades afterwards, dressed in the fashion of the day. Sometimes the effect could seem a little jarring as, for example, when brides in the 1920s tried to combine a long veil with the shorter skirts of the ‘roaring twenties’, but clearly it would not have occurred to any of them to dress in anything but the latest style. Bridal silhouettes followed fashion, right up until the 1960s miniskirts, although not all sixties brides chose this style. Hemlines moved up and down, skirts ballooned in crinolines and the 1950s ‘New Look,’ or hugged the body in the 1880s and 1930s. White was increasingly dominant.

When Paula Durance married David Dunstan in January 1973 her white minidress was in the height of fashion. She teamed it with a wide, floppy hat and white, wedge-heeled sandals for the ceremony at the Registry Office in the Old Mint building. Both Paula and David were 22 at the time and intended to go travelling together after the wedding. In fact the wedding was arranged quickly to allow them to travel together as man and wife, in deference to both sets of parents, who were concerned at their plans to travel together unmarried. Paula remembers that her dress was chosen and paid for by her mother-in-law and bought at one of Melbourne’s department stores (Myers, or David Jones). It was a white voile with blue flower sprigs.

Paula Durance and David Dunstan on their wedding day 10 January 1973

Reproduced courtesy Paula Durance

The wedding took place at the Registry Office, Melbourne Mint. In the picture (L-R) Keith Dunstan, Marie Dunstan, David Dunstan, Paula Durance, Rev. Ron Durance, Lois Durance. Paula’s minidress was in the latest style.

For some years in the early-mid-1970s there was a preference for long Empire-line dresses, which were also popular for ball gowns (while full-length gowns were still worn). Linda Blyth chose a Vogue Empire-line pattern for her wedding dress when she married Peter Summers in Ballarat in September 1972. She and her mother made the dress in a white synthetic fabric known as ‘Belinda crepe’. Linda wanted a ‘traditional’ white dress but originally intended to add some colour by threading purple ribbon through the embroidery on the bodice and flounced skirt. She simply ran out of time but compensated by choosing purple irises for her wedding bouquet, along with other Spring flowers, including hyacinth and grape hyacinth. Her shoes were Gamin, a very popular brand at the time, with a low wedge heel. She had worn the shoes as a bridesmaid at a friend’s wedding the year before but customised them by colouring in purple nail polish the two hearts appliquéd on the shoes. Linda’s wish for a traditional wedding dress did not extend to a veil. She opted for ‘something different’ instead, and chose fresh flowers for her hair, held in place by a headpiece she made using the foundation of an old hat. Peter and his best man both wore evening jackets in black velvet, with matching bow ties. Their reception for some 70-80 guests took place at the restaurant of a local motel and included a (white) wedding cake of two tiers, with moulded briar roses in pink and mauve. At the time of their marriage Linda was 21 and Peter 22. They were married for nearly 50 years and had three children — in 1981, 1984 and 1987. Linda still has her wedding dress, carefully stored. She remembers that she wore it to parties a couple of times and then packed it away.

Linda Blyth and Peter Summers Ballarat September 1972

Photographer: Ross Beacom

Reproduced courtesy Linda Summers

Colour photography was developed in the 1930s but was not generally available until much later. By the 1970s it was in common use, but the colours slowly degrade over time. Most photographers still took a variety of colour and black and white prints.

Laraine Marsden chose a very similar style for her marriage to Tony Wood in April 1973. She made the dress herself, probably from the same Vogue pattern, but with a high neckline, leg-of-mutton sleeves and a single flounce to the skirt. She called this style ‘baby doll’ and chose it partly because she felt it was ‘romantic’, but also because a full-length dress ‘was expected’ and she thought this one suited her best. Laraine was a former Catholic, who had ‘given up on the church’, so she and Tony married at the Registry Office at the Old Mint. She had no bridesmaids, but her friends all wore the mini dresses that were in fashion at the time. Her dress was made in a white spotted tulle fabric, over a pink lining.

Laraine Marsden and Tony Wood at the Melbourne Mint, April 1973

Private collection

Laraine’s Empire-line dress was made from spotted tulle over a pink cotton lining. She made the dress herself, buying the tulle in the post-Christmas sales and the pink underlining from the Victoria Market. She chose the pink lining because it was cheaper than white! Her total outlay was $30. Laraine was conscious that the style itself was ‘vintage’, but thought it was romantic. With the dress she wore Prue Acton shoes (bought in a sale), in a pale pink patent leather.

Shortly after this, in the late-1970s and into the 1980s, notions of the ideal wedding dress seem to have departed from the fashion of the day into a realm all their own. Silhouettes more reminiscent of the 1850s or 1950s were replicated in the wedding gown, (think Princess Dianna’s extravagant confection in 1981 which is still described online as ‘iconic’,) and these styles continue to be popular in wedding dresses today, along with other styles reminiscent of the 1930s and forties. Few of these gowns are likely to have another life after the wedding.

What is it about the white wedding that has made it such a resilient cultural form? Is it the notion that on her wedding day a bride is still the unrivalled centre of attention — the ‘princess for a day’? In earlier decades, the wedding day was often described as the most important day of a woman’s life, marking her rite of passage into womanhood. But that is clearly no longer the case. Perhaps it is simply the irresistible opportunity to dress up, wear an extravagant gown, and have a marvellous (and very expensive) party!

A wedding ‘with all the trimmings’

Other wedding ‘traditions’ have survived too. The wedding cake is one. It is not clear just when this emerged as an important component in wedding celebrations. Georgiana McCrae made no mention of a wedding cake in her description of the ‘breakfast’ she hosted to celebrate the marriage of Thomas Ann McCrae and Captain George Ward Cole in March 1842. She was too preoccupied with the fate of her ‘pièce de résistance’, a cold, roasted haunch of mutton, which ‘had been taken by one of the dogs from the storerooms and been so mangled that it wasn’t presentable’. ‘Happily’, she continued, the ‘things we had ordered from town’ sufficed. We are left wondering if a less ‘mangled’ haunch of mutton might have been served up regardless! Whether the ‘things …ordered from town’ included a wedding cake she does not say. She does, however, refer to another practice which continues today, if usually in a modified form, that of throwing rice over newlyweds, supposedly to wish them a lifetime of good health, and perhaps fertility. The ‘happy pair’, she noted, left for their new home ‘under a shower of rice and salt’.[iii] Similarly, the Cruikshanks, who married in 1895, ‘drove away amid a shower of rice and roseleaves’.[iv] Rice is still thrown over bridal couples, although today, paper confetti is more common.

The wedding cake

By the late-nineteenth century the wedding cake clearly played an essential part in activities at any respectable wedding breakfast or reception. In March 1898 the Australasian published a lengthy article on the topic of ‘Wedding Receptions’ and had this to say about rituals surrounding the cake.

The ceremony of cutting the wedding cake of the bride takes place when luncheon is nearly over, and the bride is assisted by two or three of the gentlemen present, including the best man. One or two of the men servants also help in this, and their duty consists in cutting up the cake and handing it to the guests. …

The health of the bride and bridegroom is proposed by one of the principal guests immediately after the cake has been cut. (Australasian, 12 March 1989, p.46.)

Maria Crocker McKenzie and her husband cutting their wedding cake, Belgrave, 1953.

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria (MM97871)

The two-tier wedding cake is decorated with a design of hearts and is topped with figures of a bridal couple under flowered arches. Maria’s wedding veil of Limerick lace was worn by over 100 women in her family over five generations. It was first worn by Janet Scrimgeour for her marriage to Danish immigrant Peter Franz Brackelmann in Bendigo in 1865. The veil remained in the family until it was donated to Museums Victoria.

Other cultural traditions

A note on different cultural traditions. The history of the white wedding described above applied almost exclusively to the Western world, until recently. In much of the East, red was the colour for brides, or red in combination with other colours. However in recent decades, the white wedding has invaded Eastern cultures too. Some now hold two ceremonies, with two different costumes — a ‘traditional’ ceremonial costume for example, followed by another celebration in a white dress. In Australia both forms exist side by side, and sometimes together.

Marriage of Naru and Jake at the Victorian Marriage Registry, Old Treasury Building, January 2022

Reproduced courtesy Naru

Although the white wedding dress continues as a firm favourite of many contemporary brides, other cultural traditions are observed within non-Western communities. Some couples choose to hold two ceremonies, one in traditional dress and the other in mainstream ‘white’. Naru chose a traditional ceremonial kimono for her marriage to Jake in 2022. The design on the kimono features a Tsuru (crane), which symbolises longevity and good fortune. It is also a symbol of marriage, since cranes mate for life. Jake also chose to wear traditional Japanese dress. Naru and Jake married in the Old Treasury Building, which has been the home of the Victorian Marriage Registry since 2004 in recent times, although early marriages might have been performed here from 1863.

May and Jeremy outside the Old Treasury Building, 2021. Photographer: Joey Mangaser Photography

Reproduced courtesy Joey Mangaser Photography

May wears a traditional Thai sari in blue silk.

Religious vs civil ceremony

One major change in the wedding has become evident however, and that is the nature and location of the marriage ceremony. Although a civil service before the Registrar was legal in Victoria from 1852 or 1853, most couples preferred to be married in a church by a minister of religion, at least for their first marriage. This continued to be the case until about 1970, but thereafter it changed rapidly. Many more couples began to prefer a location other than a church, (reception centres and gardens were popular,) while the number of registered civil celebrants also expanded. By the year 2000 half of all weddings were conducted by civil celebrants: by 2019 this had reached 80 per cent, in an almost complete reversal of former practice.

Further reading

Margaret Anderson & Alison Mackinnon, ‘Women’s agency in the first fertility transition: a debate re-visited’, The History of the Family, Vol 20, No1, March 2015, pp.9-23.

Summer Brennan, ‘A Natural History of the Wedding Dress’, JSTOR Daily, 27 September 2017.

Gordon Carmichael, Andrew Webster & Peter McDonald, ‘Divorce Australian Style: A Demographic Analysis’, Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, Vol. 26, Nos 3-4, 1997, pp. 3-37.

Gordon Carmichael ‘Non-marital pregnancy and the second demographic transition in Australia in historical perspective’, Demographic Research, Vol. 30, Article 21, 2014, pp. 609-640.

Patricia Grimshaw, Chris McConville & Ellen McEwen (Eds) Families in Colonial Australia. Sydney, George Allen & Unwin, 1985.

Margot Harker ‘This Radiant Day: A history of the wedding in Australia 1788-1960’. PhD thesis, ANU, April 1998.

Lixia Qu, Jennifer Baxter & Megan Carroll, ‘Births in Australia’, Australian Institute of Family Studies, March 2022

Lixia Qu & Jennifer Baxter ‘Marriages in Australia’, Australian Institute of Family Studies, March 2023

On the question of the invention of the tradition of the ‘white’ wedding see Margot Jane Harker ‘This Radiant Day: A history of the wedding in Australia 1788-1960’. PhD thesis, ANU, 1998, especially chap.2.

These figures are drawn from the studies published in Patricia Grimshaw, Chris McConville & Ellen McEwen (Eds) Families in Colonial Australia. Sydney, George Allen & Unwin, 1985.

Hugh McCrae (Ed.) Georgiana’s Journal: Melbourne 1841-1865. Pymble, Angus & Robertson, 1992. (First pub. 1934) pp. 61-2.

‘A Rupertswood Wedding’, Argus, 19 April 1895, p. 6.