Leaves are falling. The scent of Autumn is here. It’s football season.

Australian Rules Football was invented in Melbourne in the mid-nineteenth century ― a possible hybrid of rugby, Gaelic football and the Indigenous game marn grook (meaning ball-foot). To read more about the history of marn grook and its link with Australian Rules Fooball, see ‘Australian Rules Football as Aboriginal Cultural Artifact’, reproduced here courtesy of the author, Professor Barry Judd.

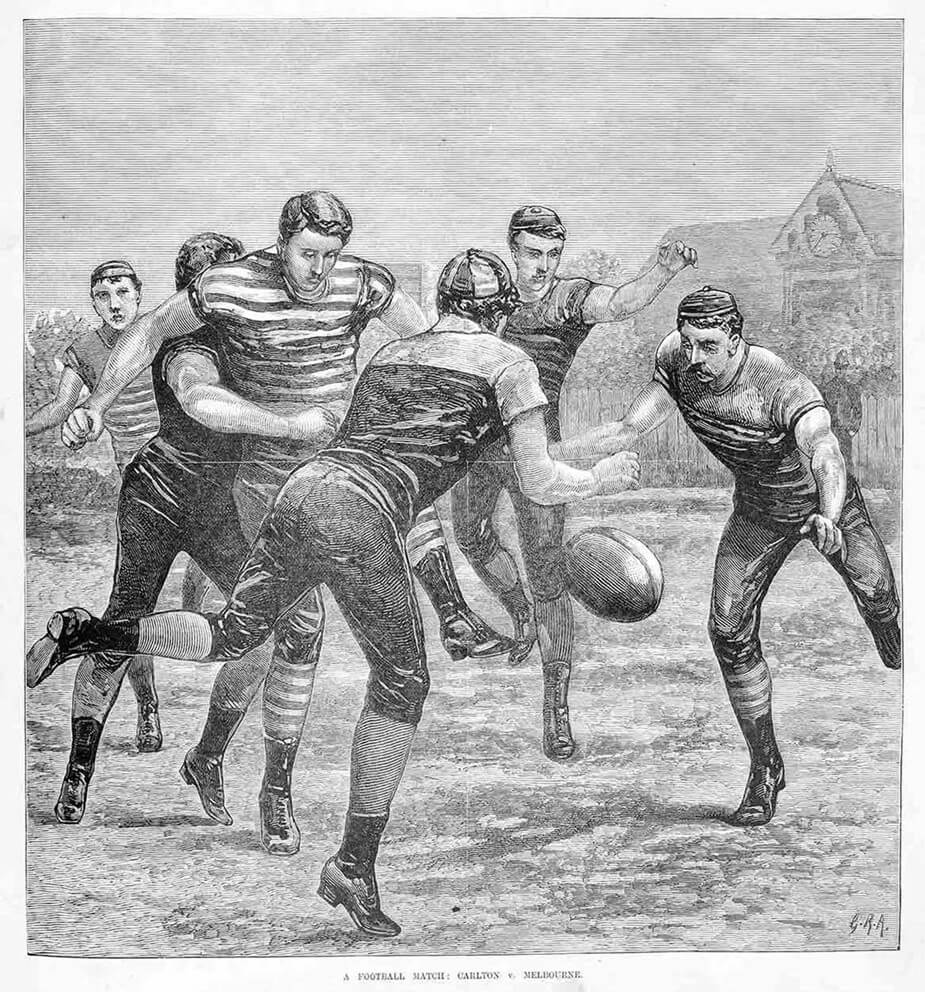

Regular games were soon played around Melbourne, with thousands of spectators gathered to watch. One game between Carlton and South Melbourne, played at the Melbourne Cricket Ground on 1 August 1890, ‘drew together the largest assemblage that has ever been present at a football match in any part of the world'.

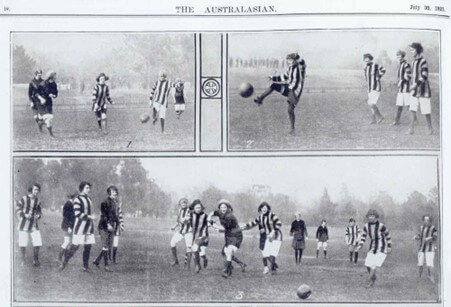

From the beginning players and spectators came from diverse backgrounds, from white-collar workers to warehousemen, Catholic and Protestant. Women also embraced the game, although initially as spectators rather than players.

Young, soft hearted girls, who would not ‘tread upon a worm’, avow that football matches are ‘awfully jolly’, and seem to regard accidents as a necessary part of the amusement. At the contest of the reds and the blues, a great proportion of the spectators were ladies’.

Viva, ‘Football: A Social Sketch’, Weekly Times, Ladies Newspaper supplement, 3 July 1886

Football Clubs formed within suburbs and choosing a team was based heavily on suburban influences: ‘Be it the working class of the Collingwood Football Club or the white-collar members of the Melbourne Football Club, supporter bases formed around a shared sense of identity’. Chris Hickey, Professor of Health and Physical Education, cited in ‘How choosing an AFL team defines Melburnians’.

Loyalty to an AFL team is usually forged in childhood: allegiance is dynastic and very often non-negotiable. According to a recent AFL survey, 70 per cent of supporters deemed it unacceptable to swap teams, regardless of age or reason. A ‘mixed footy marriage’ requires sacrifices. Historian (and footy fanatic), Joy Damousi, claims these can only be managed through a ‘shared amnesia’— the ‘pretence that nothing is actually happening punctuated by secretive dashes to the car radio to check out the score.’

Today ‘footy’ is played in schools, on suburban football grounds and country fields, city streets and backyards. Elite players compete in Australian Football League (AFL) and, more recently, the Australian Football League Women’s (AFLW).

For passionate fans, Australian Rules Football is firmly embedded in family life. Watching, talking and reading about ‘footy’ can take up endless hours. Team jumpers and handknitted scarves are passed from one generation to the next and going to the football has become a family tradition. The footy ‘fanatic’ might seem a bit mad to some people but, for most, supporting a team provides a sense of belonging and community and is inextricably linked to memories of family.

Australian football, or to be more accurate, supporting the Collingwood Football Club, has been central to my family’s life for five generations, spanning from 1892 through to the present. My family have spent their weekends packing scarves, raincoats and food, as well as travelling long distances, if necessary, to watch our team play. To date members of my family have been present for approximately 2500 home and away matches, 177 finals matches, 43 Grand Finals and 16 premierships (one during the time Collingwood spent as part of the Victorian Football Association, 13 when they were part of the Victorian Football League and two Australian Football League premierships). During this time there has been a Depression, two world wars, a cold war, a cultural revolution, the ‘space race’ and the move from the Industrial age to the Digital age. The one constant in my family’s life over many generations has been supporting the Collingwood Football Club.

… my family has slept outside football grounds on cold nights, hoping to secure the much sought after finals tickets. We have sat in the pouring rain watching our team receive absolute thrashings at the hands of hated rivals. We have laughed, cried, fought, hugged and screamed ourselves hoarse ― at the football at first in Melbourne and, since the competition has become national, and our team has to play matches outside our state, watching some games together in front of the television. Each game that we attend seems to provide us with more stories and more memories to add to our family history as devoted Collingwood supporters.

Catherine Farrell, ‘Footy Sheilas: A Memoir and Exegesis’, 2016

‘Footy’, as the cliché goes, is a secular religion. And like a religion, it involves rituals, including wearing team colours. Coloured scarves, hats, socks, jumpers, even underwear, are worn at football games as a show of allegiance to the team and to each other.

Selecting clothes might be considered a routine where little conscious thought is given before and after the act. However, as football supporters, selecting the ‘right’ clothes that have some sort of symbolic meaning (for example, a lucky scarf or jacket) to wear to the football is part of the rituals of following a football team.

If Collingwood won then we were under instruction from my Mum and my Granny that we had to wear exactly the same clothes right down to our ‘undies’ at the next game. If we lost then we weren’t allowed to wear the same clothes again for the rest of the season… Over the years my long blue coat, my mustard parka, my duffle coat and my magpie undies have all been banned from attending any matches.

Catherine Farrell, ‘Footy Sheilas: A Memoir and Exegesis’, 2016

On display in Belongings: Objects and Family Life, we have this Carlton Football Club jumper, kindly donated by David and Elizabeth R. David bought this jumper for his daughter Ellie when she was aged seven. David and Ellie live in regional Victoria but are avid supporters and attend games together when they can. Ellie’s allegiance to Carlton was inherited from her father and paternal grandfather. It was not up for discussion.

Now that cricket has been put aside for some few months to come, and cricketers have assumed some-what of the chrysalis nature (for a time only ‘tis true), but at length will again burst forth in all their varied hues, rather than allow this state of torpor to creep over them, and stifle their new supple limbs, why can they not, I say, form a foot-ball club, and form a committee of three or more to draw up a code of laws.

Tom Wills, cricketer, 19 July 1858

The first game of football was played in 1858 between Scotch College and Melbourne Grammar in the Richmond Paddock. By the 1870s the game had flourished as a spectator sport, benefiting from the affluence of Gold Rush colonists, shorter working hours, a growing public transport system and significant press coverage.

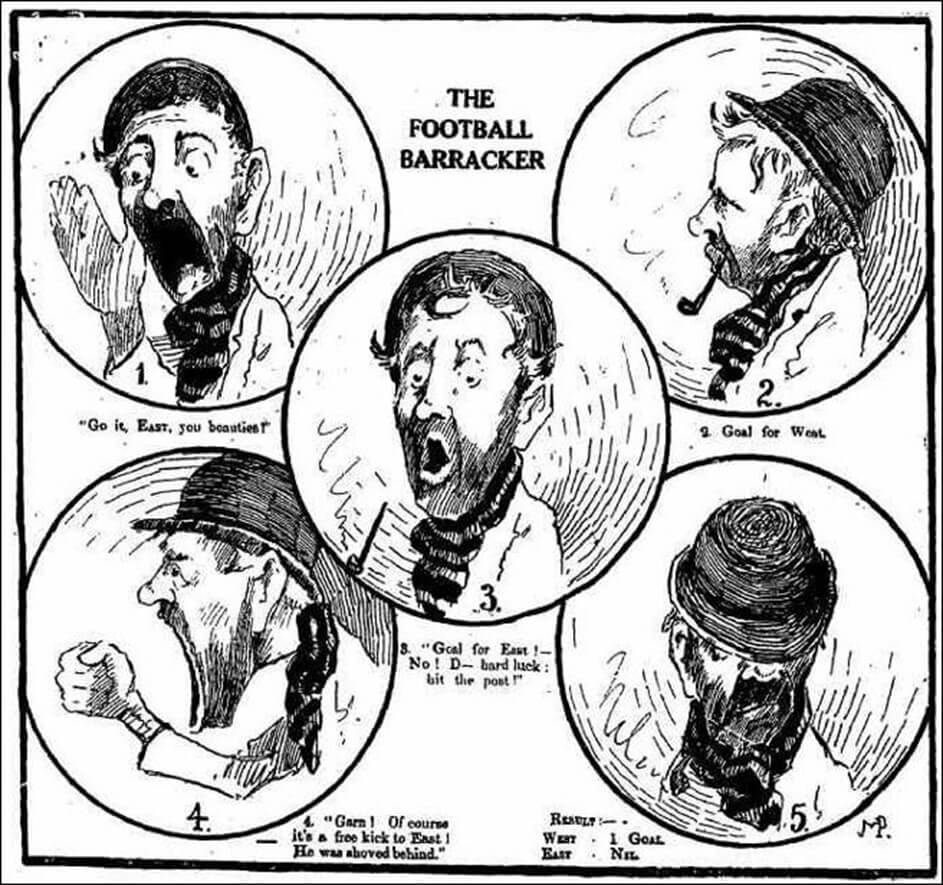

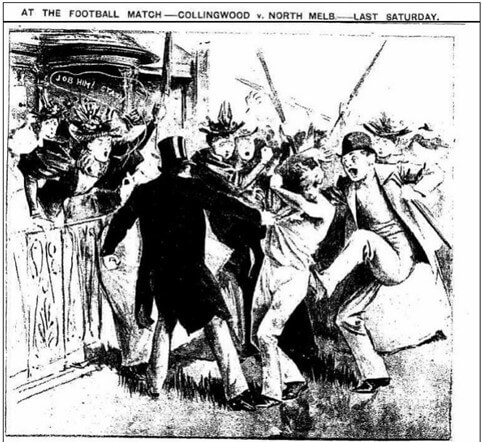

The term ‘barracker’ was coined in the 1870s and referred to the act of barracking ― shouting abuse or encouragement to players and officials. Initially it was a derogative term, applied to working-class spectators.

By the 1890s crowd behaviour had become unruly. There were incidences of swearing, threatening to hit or kill the umpire. Women came under special scrutiny in the press:

On some grounds they actually spit in the faces of players as they come to the dressing-rooms, or wreak their spite much more maliciously with long hat pins…

Women today account for some 40 percent of football crowds, more than any other ‘football’ code in the world. Thankfully less comment is made about the intensity of women’s involvement.

'A good football match in Melbourne is one of the sights of the world.' - R.E.N. Twopeny, Town Life in Australia, 1883

What is this coming down the street? It proclaims itself to be a funeral. But it seems to lack solemnity. It is burlesque or effigy business. Have the unemployed slain another tyrant, and do they carry him now through the streets? Nay, there is too much colour here. The red and white seem crossed on the manly chest, and the blues are bearers and mutes and mourners. This is Carlton burying South Melbourne – South Melbourne whom they propose to vanquish utterly this afternoon, for it is Saturday afternoon, and not yet three of the clock.

The Argus, 4 August 1890

By the 1870s football matches attracted huge crowds, who at that time watched free of charge. Journalists likened the spectators to a Roman crowd, and the players gladiators. They marvelled at the many ‘willing to brave the chill air of a winter's afternoon to witness the match'. Little has changed. On any given weekend, and in all weather, AFL stadiums are packed with supporters.

Since the late-nineteenth century a few determined women have played the game, creating their own local competitions. But it took over 150 years to develop a professional female league, the Australian Football League Women’s (AFLW).

Nicky Winmar lifts his jumper and points to his skin, telling the crowd, and the rest of Australia, that he is black and proud of it. This image remains one of the most powerful anti-racism symbols in Australian history.

Photograph of Nicky Winmar, Victoria Park, by Wayne Ludbey, photographer, 1993. Reproduced courtesy The Age

Australian Rules Football has a long history of First Nations involvement. Soon after the game's invention, football teams emerged in mission communities at Coranderrk, Lake Tyers and Framlingham in Victoria, and First Nations players have competed in the AFL (then known as the VFL, Victorian Football League) since 1904. Some found social mobility through their football careers. Sadly, a small minority of barrackers use racist taunts.

Read about the AFL apology to Adam Goodes here.

Football Season brings memories of times shared with family and friends. We asked staff and volunteers at the Old Treasury Building to contribute some of these memories.

I have been a Western Bulldogs member for 20 years ― impressive considering I’m only 26! Dad (Derek), an immigrant from Scotland, moved around a lot as a kid. Eventually, his family settled in Williamstown and as all good Western Suburbanites do, he followed the Western Bulldogs (then Footscray) Football Club.

My dad signed me up from a young age and I’d follow along to games, where I initially spent more time looking at my coloring book and pencils than the actual game. Mum couldn’t give a hoot about football, so I think Dad tried to mould me into the perfect little footy companion ― and it worked. Soon I was screaming ‘BALLLLL’.

Here we are on Grand Final Day 2016, with the house all decked out in red, white and blue. The atmosphere at the MCG was electric and we cried together when the Bulldogs won. Dad even got a tattoo to celebrate! When we’re not working, we still go to the footy together. We’ve even converted my partner Ryan into a Bulldogs fan and he comes along too.

Paige Morrison

‘Collingwood’ dolls, knitted by Anita Lenkic, 2023

Reproduced courtesy Anita Lenkic

This is my Collingwood Football Club story. My family arrived in Melbourne on 10 September 1951; I was aged 10. We were sent to the Ballarat migrant camp in October of that year. By April 1952 we had found a place to live on Black Hill, a small suburb of Ballarat. I was enrolled at Black Hill Primary School into Grade 4.

On my first day of school the teacher introduced me to the class. I sat in the only empty chair, next to Patty Smith. I had no school supplies with me, as in England all requisites were provided. l had only a piece of paper and a pencil given to me by the teacher. I was asked to rule lines on my paper, but l had no ruler. So, l turned to Patty and said, in my strong Manchester accent, "Can l use your ruler?" Patty answered: "Yes you can, as long as you barrack for Collingwood!" I had no idea what ‘Collingwood’ was, nor did l know what a barracker was, but l answered "Yes!". Throughout the year Patty would tell me how Collingwood had done over the weekend. I had no idea what she was talking about. One day, after watching the boys playing a game in the school yard, it dawned on me ― she was talking about Aussie Rules Football. Patty also told me the Collingwood team were called the ‘Magpies’. l had no idea what a Magpie was. When l learnt it was a bird l made the connection between the team colours and the team symbol.

Over the next few years l became a firm Collingwood FC supporter. Sadly, l have never seen a game live, but I bleed Black and White blood. For a newcomer to Australia, finding a team to follow allows you to fit in and feel comfortable. As a ‘Magpies Tragic’, l bless the day that Patty uttered those fateful words ― "Yes… as long as you barrack for Collingwood!'.

Anita Lenkic

That photo was taken at my place before leaving for the AFL Preliminary Final at Waverley. 21 September 1991. Mum was 74. I had three tickets to the game; Dad decided he preferred to stay home and tile my kitchen.

I regularly drove to Adelaide and on one Easter Saturday I procured tickets to the Adelaide Crows/Carlton game at Football Park. My car was fairly new and of course had a Victorian number plate. I didn’t want to take it to the football and risk malicious damage to the car by feral Crows supporters. Dad told me to drive his much older, SA registered car instead and suggested “see if you can get it pinched”.

Gail Thornthwaite

Further reading

Online sources

NMA- Australian Rules football

Publications

Barry Judd (Prof), ‘Australian Rules Football as Aboriginal Cultural Artifact’, The Canadian Journal of Native Studies XXV, Issue 1, 2005

Barry Judd (Prof), Tim Butcher, ‘Beyond equality: The place of Aboriginal culture in the Australian game of football’, Australian Aboriginal Studies, Issue 1, January 2016

Catherine Farrell, ‘Footy Sheilas: A Memoir and Exegesis’, Doctoral thesis, Swinburne University of Technology, 2016

Cheryl Critchley, ‘Footy isn’t life or death – it’s more important’

Chris Mcconville, ‘Footscray, Identity and Football History’, accessed online

Deborah Hindley, ‘In the Outer – Not on the Outer: Women and Australian Rules Football’, Doctoral thesis, Murdoch University, 2006

Gillian Hibbins, ‘Myth and History in Australian Rules Football’, Sporting Traditions, Vol. 25, No. 2, November 2008

June Senyard, ‘Marevellous Melbourne, consumerism and the rise of sports spectating’, in Matthew Nicolson, ed., Fanfare: spectator culture and Australian Rules Football, Balaclava, Victoria, Australian Society for Sports History, 2005

Matthew Klugman, ‘Female Spectators, Agency, and the Politics of Pleasure: An Historical Case Study from Australian Rules Football', The International Journal of the History of Sport

Matthew Klugman, ‘On Barrackers and Barracking’, Oz Words, Vol. 28, No. 1, April 2019

Sean Gorman, Barry Judd, Keir Reeves, Gary Osmond, Matthew Klugman & Gavan McCarthy, ‘Aboriginal Rules: The Black History of Australian Football'