The colonist is very committed to living in his own house and on his own bit of ground, and building societies and the extensive mortgage system which prevails enable him easily to gratify that desire. Richard Twopeny, Town Life in Australia, 1883.

Home ownership is important to Australians. It is deeply embedded in our national psyche, a cornerstone of what is often called the ‘Australian Dream’, or ‘the Australian way of life’. This sense developed early. From the middle decades of the nineteenth century, a separate dwelling with its own garden became a powerful ingredient in the way we imagined family life, and over the decades it has shaped our lived experience of family to a significant extent. Indeed, Graeme Davison argues that Australians consistently judged their standard of living by how well they were housed.[i]

The first houses were of necessity simple constructions, built of local timber, often wattle and daub, with thatched roofs and the kitchens set at some distance from the house for fear of fire. But already in 1860s Melbourne timber houses were being replaced by brick and stone, while thatch gave way to slate or timber-shingled roofs. In contrast to town dwellings in Britain or Europe, most of these houses were single dwellings in their own yards. Even a small garden was preferable to nothing! Unlike London or Edinburgh, Melbourne had no tenements housing working people. That is not to say that there was no poor housing. By the 1880s and 1890s Melbourne was notorious for its ‘slum’ districts around Little Bourke and Little Lonsdale streets in the city, but almost all were single-storey dwellings with some yard front and back. By the 1930s the ‘slums’ had expanded in the middle-class imagination to include Collingwood, Footscray and Carlton in the inner suburbs, but despite determined campaigns by well-meaning social reformers, successive Victorian governments were reluctant to provide alternative public housing.

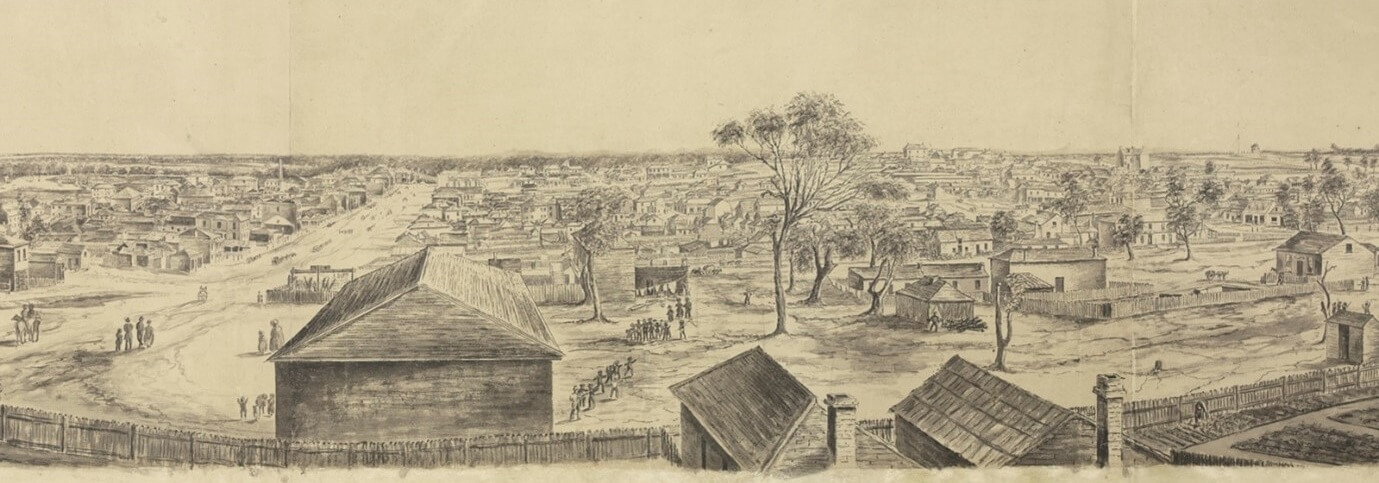

Samuel Jackson Panoramic Sketch of Melbourne Port Phillip from the walls of Scots Church on the eastern Hill July 30th 1841, excerpt.

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Most of the structures shown are simple dwellings of wood with shingled roofs, but each is set in its own plot of land. Within twenty years almost all had been replaced with buildings of brick and stone.

S T Gill Lucky Digger that returned, watercolour, 1869

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

Colonial artist S T Gill’s representation of a ‘lucky digger’ showed a man with his wife and child in a comfortable home. Note the solid furniture, books and papers on the table, pictures on the walls and ornaments on the mantlepiece above the fireplace.

From the time of the gold rushes onwards, many of those who came to Victoria as migrants hoped, eventually, to own a home of their own. Those who could afford it, moved their families into the growing suburbs on the periphery of the city, travelling into town for work or to shop on horse-drawn omnibuses, and later by train. Colonial architects modified British standard house designs for suburban cottages and villas to suit local tastes, adding the verandahs popular in India for summer shade. Soon such cottages and Italianate villas dotted suburbs like Hawthorn to the east, Brighton to the south-east, and even Brunswick to the north. Would-be homeowners were assisted by Victoria’s relatively high wages, the availability of affordable land, and credit from building societies ready to lend to those with steady incomes. Houses also increased in size. In the first decades many were only two or three-roomed cottages, but by the 1860s and seventies five rooms or more were increasingly common. A house of five main rooms would continue to be a popular design well into the 1930s and the post-war period. It generally consisted of a ‘living’ room, a dining or ‘breakfast’ room, two bedrooms and a kitchen. Laundries were often separate spaces, either attached to a back porch or a shed-like structure in the back yard. Few nineteenth century homes had bathrooms or internal water closets. Until well into the twentieth century the WC was usually an earth closet or pan closet placed against the back fence, where the pan could be emptied weekly by a ‘nightman’.

Home ownership increased in Victoria until by 1891 about 42 per cent of occupiers in Melbourne either owned, or were buying, their own homes. The proportion was higher in rural areas and in mining towns. Few places in the world exhibited similar rates. And yet it was a fragile dream. When a deep recession struck the Colony in the 1890s, working people who were buying their own homes suffered immediately. The housing industry was the first to collapse, along with associated industries like brickworks and roofing factories. As industry closed and wages dried up, so the banks and building societies foreclosed on desperate owners. It was said that during the 1890s Depression whole streets in Brunswick were empty, with houses boarded up against squatters, as the local brickworks, the major employer in the area, closed its doors.

A house with a garden

The house itself, along with its associated garden, was always an important indicator of a family’s wealth and status. Of course large houses, especially those with equally large gardens, required a great deal of work to maintain, and the families who lived in them usually employed both household and outdoor servants to do the work. Some of those servants might be accommodated on site, generally in small attic bedrooms, or in quarters attached to the kitchen or stables. Indoor servants generally worked a 12-hour day (or more), beginning at six in the morning and often extending well after the evening meal at night. They might have every other Sunday off, depending on the mistress concerned. The design of such houses differed substantially from that of the smaller villas, and generally included large reception rooms on the ground floor (a drawing room, dining room and/or a library), along with a smaller ‘morning’ or breakfast room where the ladies might sit to ‘work’ (sew) in the morning. A large kitchen complex, often including both kitchen and scullery was often included on the ground floor at the back of the house, separated from the main house by a servants’ passageway. Bedrooms in very large houses might be upstairs, and from the 1880s there might well be a bathroom, sometimes with an internal water closet.

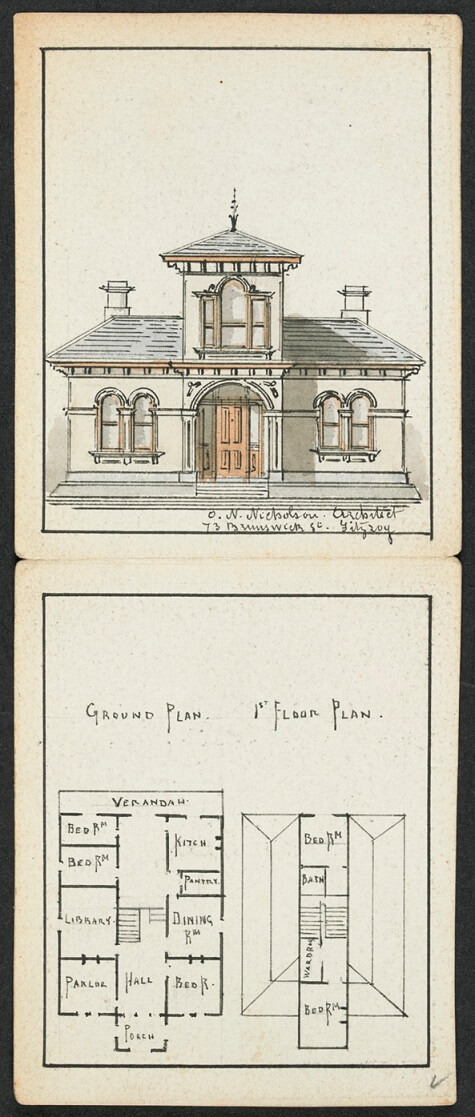

Architectural plan and elevation by O N Nicholson, Architect, 1882

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria (Ref. 9939670540207636)

This plan was for a large dwelling on Brunswick Street Fitzroy. It was a two-storey residence, with a parlor, dining room, large library, kitchen, and scullery downstairs, and what were probably intended to be two servants’ bedrooms near the kitchen. There were three ‘family’ bedrooms, two upstairs along with a bathroom (but no WC) and one bedroom downstairs. There was no laundry.

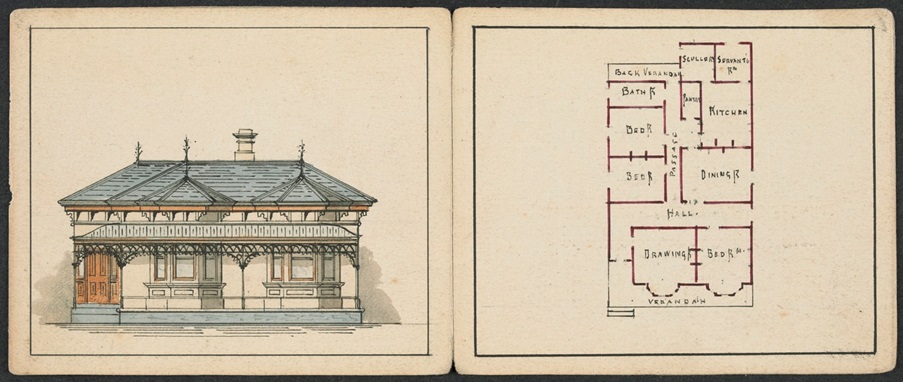

Architectural drawing and elevation for a villa residence by O N Nicholson, c. 1882

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria (ref. 9939656050807636)

Also designed for construction on Brunswick Street Fitzroy, this was a smaller villa. It comprised a drawing room, dining room, three bedrooms, a kitchen and bathroom all on the ground floor. There was also a (single) servant’s room off the kitchen and adjoining the scullery. Once again, no WC is shown and there was no laundry. The latter was probably intended to be housed in a separate structure in the back yard.

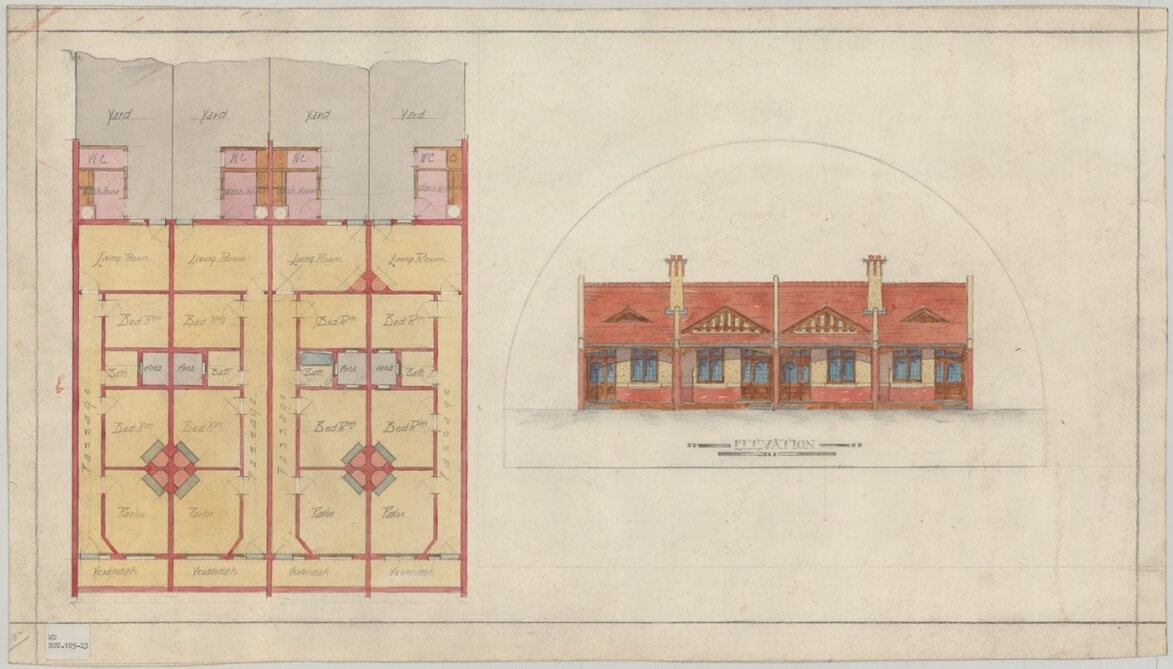

Sketch plan for a Terrace Row of four single storey houses, by architect William Pitt (1855-1918), c. 1910

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria (Ref: 1796833)

There is a world of difference between the substantial villas designed for the middle class and these simple row terrace houses intended for working families, although these designs were probably considered model housing of the period, since they contained an internal bathroom, with a washhouse and WC attached to the back porch. Admittedly the WC and wash house were accessed from outside, but this was a common feature of housing into the 1930s. These simple, single-fronted row cottages had two bedrooms, a parlor and a ‘living room’, presumably a kitchen/eating area.

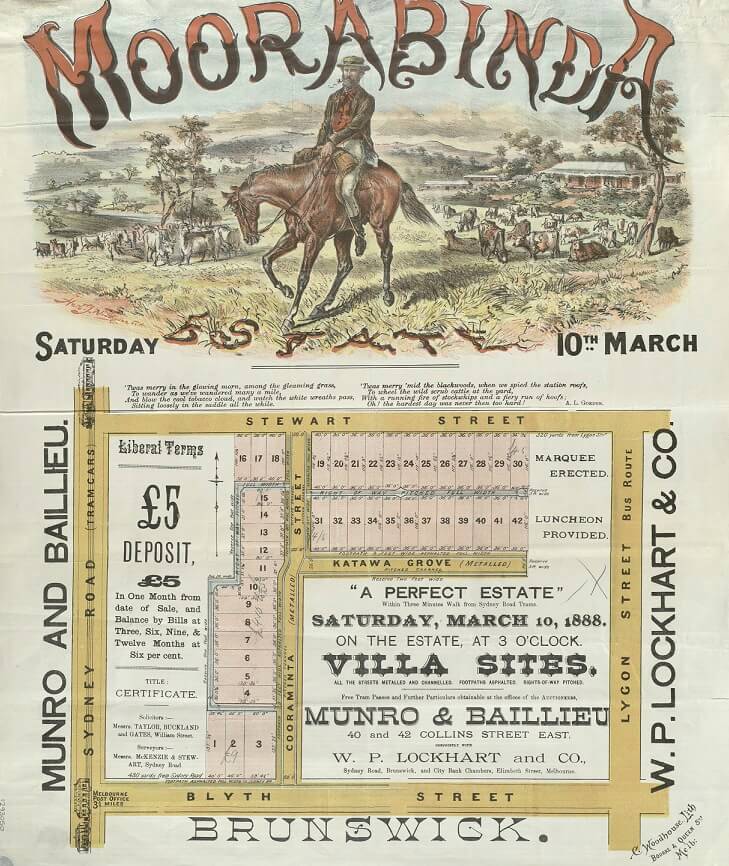

Auction plan, Moorabinda Estate, Brunswick, 1888

Reproduced courtesy State Library Victoria

One of many subdivisions designed to appeal to working people. The poster promised ‘liberal terms’ and ‘villa sites’ on ‘A Perfect Estate’. Most of the allotments were small, but they did offer space for both a modest house and a garden plot. The seller also offered a 12-month payment plan, with a minimum deposit of £5 and other payments at intervals of three months at 6 per cent interest.

Edith and Arthur Farmer, with Hazel and Avis, West Brunswick, 11 January 1920

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria (MM42073)

This is a modest residence, in Dalgety Street Brunswick West, then a working-class suburb. The front entrance is reached via a trellis attached to the verandah, with vines and other plants in evidence. Two watering cans suggest how the garden was managed. The girls’ overcoats hint at a cool day (the maximum reached was just 20 degrees C.), but it would be 41 degrees on two successive days in the following December! Vines grown up a trellis might have helped to keep the house cooler on such extremely hot days.

Assisting home buyers

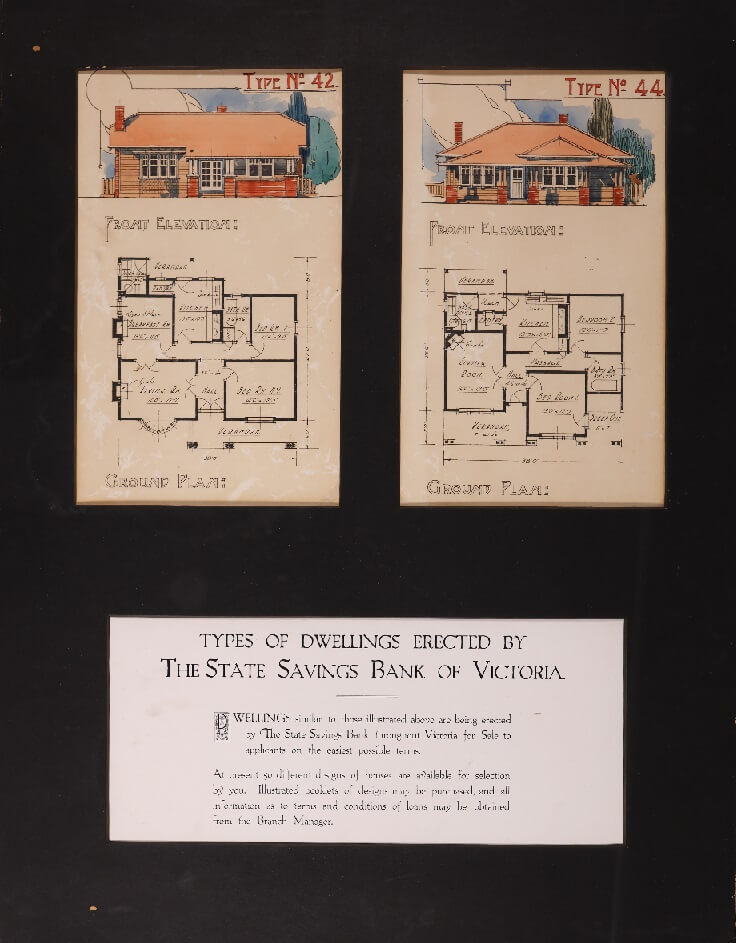

Just as the family was seen as the desired basis for a virtuous society, so home ownership was encouraged by successive governments to promote social stability. One important initiative in Victoria was the State Savings Bank of Victoria’s Home Building Scheme. This program was designed to assist first home buyers who earned less than £400 per year to build on their own land, or on blocks of land purchased from the bank. Purchasers required a ten per cent deposit and had to maintain a savings account at the bank for some years before they qualified for a loan. This was intended to demonstrate their capacity to save. Long-term loans were then made available at low interest rates to build homes, with the bank holding title to the land as collatoral. The scheme began in 1910 and was soon a great success, both socially and financially for the bank.

At first the value of the loan was capped at £800, and this was all-inclusive, meaning land, construction, sewerage, outbuildings, fencing, lighting, water supply and drainage. Buyers also had to pay for the house plans and for supervision of construction. However it was soon evident that this was not sufficient to cover the cost of building brick homes, and in 1922 the cap was increased to £850 for timber homes and £950 for brick. The loan was repayable monthly at 8.5% per annum, including interest at 6.5%. In the 1920s the bank established its own Building Department, which provided architect-designed house plans, with detailed specifications for both brick and timber-framed dwellings. Regular tenders were called from prospective builders and the bank supervised the subsequent build. Not surprisingly, such ‘bank houses’ acquired an enviable reputation for quality.

The Great Depression of 1929 saw a temporary pause in the bank’s home lending scheme, although it did carry out repairs. The bank also proved more understanding of financial distress than other lenders, reducing interest rates on loans to a maximum of 6% in 1931, and then 4.5% in 1934. Some loans were reduced to interest-only for some years. By the mid-1930s as conditions improved, the bank resumed the scheme. At that point prospective owners could choose from some 50 house plans. We show just two examples in the exhibition.

At this stage there were none of the display villages that would come later and no three-dimensional imaging either, so the bank produced cut-out models to scale. These could be assembled to show buyers what their homes would look like. We show one of these models (assembled) in the exhibition and have also reproduced a model for visitors to purchase to make at home.

These plans show simple two-bedroom houses, with a ‘living room’ at the front and a ‘breakfast room’ adjoining the kitchen. Each house also has a small internal bathroom, with a bath but no toilet, and a back porch giving access to a laundry (‘wash house’), equipped with copper and two troughs. Adjacent to the porch and wash house is a WC, but it is interesting that in each case the WC is accessed externally, rather than from the porch, forcing users to go outside.

Some local councils were also very active in promoting home ownership. The Port Melbourne Council lobbied strenuously in the 1920s for affordable housing to be built on reclaimed land in the area. Eventually the Savings Bank of Victoria stepped in and offered house plans to build new homes for sale on 18 hectares of land they purchased in 1926. The subdivision was designed on popular ‘garden city’ principles and ultimately included 322 semi-detached dwellings built to six designs. The bank made loans available at affordable interest rates, with the property held as collateral (known as credit foncier).

Housing the poor

Meanwhile those on very low or precarious incomes struggled to rent in crowded, low-cost accommodation in the inner city and surrounding inner suburbs. Here poorly-built houses often fell into disrepair, as landlords baulked at even routine maintenance. Low-lying suburbs near the river were subject to flooding. Before the city was deep sewered in the early twentieth century, cesspits overflowed regularly and outbreaks of typhoid and other enteric disease were common. In vain, groups of concerned citizens called for what they called ‘slum clearance’, but government was reluctant to demolish sub-standard housing when poor tenants had no alternative accommodation. There was little appetite in government to construct what we now call ‘social housing’.

In the wake of the Great Depression however, there was something of a change of heart. Social advocates like Frederick Oswald Barnett and the Housing Reform Council (later known as the Slum Abolition and Better Housing League) documented conditions in Melbourne’s ‘slums’. Their photographs of living conditions in the inner suburbs, published in newspapers like the Herald, shocked complacent Melburnians and prompted government to create the Housing Commission of Victoria in 1937.

The Housing Commission had a brief to improve housing conditions for low-income families and to develop low-cost accommodation (both rental and for sale). One such development was located in Port Melbourne, on 22 hectares of land adjacent to the State Bank’s Garden City development. Here the Housing Commission built accommodation to rehouse large ‘deprived’ families in the late 1930s. In what would become a familiar story, this development did not meet with the approval of some of the residents of Garden City, and tension simmered on and off between the homeowners of ‘Nob Hill’ and the tenants of what was derisively dubbed ‘Little Bagdad’.

War and an acute housing shortage

The Housing Commission had barely begun its task when the Second World War intervened. All house building ceased immediately as resources were allocated to the war effort. With the combined effect of the Depression, followed by war, Victoria’s housing supply was in crisis, with an estimated shortfall of housing in 1945 of 350,000 homes. People were living in all sorts of ramshackle structures, from garden sheds to converted garages, while many newly-weds were forced to move in with in-laws. Even those who could afford to buy housing could not always get permission to do so (my parents amongst them).

Those with the requisite skills sometimes built their own homes: the 1950s was a boom time for DIY home builders! Museums Victoria has preserved the story of one group of Ukrainian immigrants, who arrived in Victoria as Displaced People after the Second World War. After initial periods on (required) government work assignment, Ivan Kucan and five friends came to Melbourne looking for land to settle. They all bought land in the same street in Newport and helped each other to build their homes.

Post war economic boom

As the country recovered from war, there was a marriage boom, a baby boom, and not surprisingly, a home building boom. Home ownership rates, which plateaued during the war, rose to 53% in 1947 and kept rising. Full employment after the war helped a record number of Victorians aspire to home ownership and it reached a peak in 1966 at 71%. (The rate now hovers around 63%.) Both state and federal governments funded programs to assist first-home buyers with subsidised finance at this time, but social housing for the poor was not a priority. In 1960s Victoria public housing only accounted for about 5% of all housing stock.

Nevertheless, the Housing Commission soldiered on, building a mix of houses and flats, some in huge high-rise blocks in inner suburbs like Carlton and Fitzroy. These were controversial at the time and continue to attract criticism now. As recently as 2020 one high-rise block was the subject of a press storm after its residents were confined in lockdown during the COVID pandemic. The lack of amenities in these blocks, like access to fresh air from balconies, was a point of contention. However, the Commission also built many single dwellings and from 1943 could offer lease and rental options to occupiers who wished either to rent or to purchase a home. Many were delighted to be allocated a home, especially those who were new migrants like the Duncans and the Beedles shown here. The Housing Commission was eventually abolished in 1984, but the current acute shortage of affordable housing has led to suggestions that some similar body should be reconstituted.

Family members outside their Housing Commission home, West Heidelberg, Christmas Day 1950

Reproduced courtesy Museums Victoria (MM110792)

Shown are members of the Duncan and Beedle families, including Ann (centre),

Russell and Rosemary Beedles, with cousins Elsie and George Duncan. Ann Beedles and Frances Duncan were sisters. The two families lived together for a year while the Duncans, recent migrants, waited for a house to become available. They were thrilled to find one just up the street.

For other prospective home buyers there was a veritable feast of options. Building companies, like A V Jennings, offered package deals of design and construction, with buyers choosing from varied design options. Most of these were designed on new modernist lines, with fewer hallways and more open-plan layouts. While these did not necessarily reflect buyer preference, what began as a post-war austerity measure, continued into 1960s and seventies house design. Companies also began to construct display homes, sometimes clustered in villages to demonstrate design options. Visiting display homes became a weekend pastime for newlyweds hoping to buy.

Houses in the 1960s began to be larger, with three bedrooms increasingly common. The house plans shown here all have bathrooms, generally with a separate WC and a laundry under the main roof. Some of the WCs are accessed internally, others from a porch or laundry. The laundries all seem to assume the use of a washing machine.

The Garden

Family life in the post-war period was strongly influenced by the tendency for Victorians to establish homes in discrete dwellings set within a garden. There was a preference for large back-yards in particular and these were often put to productive use. Vegetable plots and fruit trees were common, along with a patch of lawn ‘for the kiddies’. Front gardens were often given over to ornamental plantings, including roses and flowering trees, although European migrant families often preferred useful trees like figs and persimmons, while vines adorned the fence line. Some of these plantings can still be seen in older gardens in suburbs like Brunswick and Carlton. Water was plentiful and relatively cheap, enabling householders to water their plots with abundant sprinklers. A frolic under the sprinkler on a hot day became a quintessential experience of childhood.

This was a popular summer pastime of the Brocklesby children and of many other children before and since. Such activities gave some relief from the summer heat at a time before most houses were airconditioned. A wood pile against the back fence hints at a wood fire for heating in the winter, or perhaps a wood stove, although these were far less common by the fifties.

Domenico and Domenica migrated to Australia from Calabria in 1960 along with their three children. Domenico had been a subsistence farmer in Calabria and maintained an extensive productive garden in Brunswick and then in Reservoir. For many migrant families, such gardens provided a tangible link with home, but also a means of preserving cultural traditions through foodways.

While both men and women gardened, there were some common assumptions about appropriate gender roles. Until recently, lawn mowing was a task assigned to men. In some suburbs, maintaining a well-manicured front lawn was an important indicator of social respectability. Apparently, it was a skill that could not be learned too young!

The family home expands

In the 1970s as family size continued to fall, houses expanded even further. ‘Family’ rooms were added, generally in the space near the kitchen, additional bathrooms made an appearance, (especially an ‘ensuite’ entered from the main bedroom) and some plans added ‘parents’ retreats’ and cinema rooms. Outside, well-tended vegetable gardens and fruit trees began to give way to in-ground pools, barbeque areas (sometimes with in-built pizza ovens) in spaces increasingly described as ‘outdoor living areas’. At the same time, a counter trend began to emerge with young families and ‘empty nesters’ moving into home units and apartments, sometimes in the inner city. As the cost of housing rises in the twenty-first century, more and more families may seek this less-costly solution. However, apartment design has been slow to adapt to this new demand from families with children and there is considerable anxiety in the community at what is increasingly seen as ‘Australia’s housing crisis’. High house prices, leading to unsustainable mortgages, and a growing shortage of affordable rental accommodation, is squeezing families at all income levels. Despite the growing popularity of town houses and apartments, the concept of a single dwelling on a plot of land, however small, is still a powerful ingredient in our shared imagining of the ideal family home.

Further reading

Trevor Craddock and Maurice Cavanough 125 years, the Story of the State Savings Bank of Victoria. 1967

Graeme Davison, ‘Housing’, in Graeme Davison, John Hirst & Stuart Macintyre (eds) The Oxford Companion to Australian History. Melbourne, Oxford University Press, 1998, p. 327.

Graeme Davison, ‘Colonial Origins of the Australian Home’, in P. Troy (ed.) A History of European Housing in Australia. Cambridge University Press, 2000, pp. 6-25

Peter Cuffley Australian Houses of the Twenties & Thirties. Melbourne, Five Mile Press, 1993

Peter Cuffley Australian Houses of the Forties & Fifties. Melbourne, Five Mile Press, 1994

Tony Dingle & Seamus O’Hanlon, ‘Modernism versus domesticity: The contest to shape Melbourne’s homes, 1945-1960’, Australian Historical Studies, Vol. 27, No. 109, October 1997, pp. 33-48

Tony Dingle, ‘Self-help Housing and Co-operation in Post-war Australia’, Housing Studies, Vol. 14, No. 3, May 1999, pp. 341-354

Don Garden Builders to the Nation: The A.V. Jennings Story. Melbourne University Press, 1992

Renate Howe New Houses for Old: Fifty years of public housing in Victoria, 1938-1988. Melbourne, Ministry of Housing & Construction, 1988

Renate Howe, David Nichols & Graeme Davison Trendyville: The Battle for Australia’s Inner Cities. Monash University Publishing, 2014

Seamus O’Hanlon, ‘Modernism and prefabrication in post-war Melbourne’, Journal of Australian Studies, Vol. 22, No. 57, January 1998, pp. 108-118

Seamus O’Hanlon, ‘“Six-packs and villa units”: flats in Melbourne in the 1960’s and 1970’s’, in David Nichols, Anna Hurlimann, Clare Mouat & Stephen Pascoe (eds) Proceedings of the 10th Urban History, Planning History Conference. University of Melbourne, 2010, pp. 424-434

Seamus O’Hanlon, ‘The reign of the six-pack: Flats and flat-life in Australia in the 1960s’, in Shirleen Robinson & Julie Ustinoff (eds) The 1960s in Australia: People, Power and Politics, Newcastle upon Tyne, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2012, pp. 33-50

Seamus O’Hanlon, ‘Selling “lifestyle”: Post-industrial urbanism and the marketing of inner-city apartments in Melbourne, 1990-2005’, in Steven High, Lachlan Mackinnon & Andrew Perchard (eds) The Deindustrialized World: Confronting Ruination in Postindustrial Places. Vancouver, University of British Columbia Press, 2017, pp. 232-53